A conversation between Dr. Salaam al-Kuntar and Dr. Steven Zucker about the ancient city of Palmyra while looking at six Palmyrene funerary reliefs , c. 150-200 C.E., varying dimensions, limestone (The Metropolitan Museum of Art). An ARCHES video.

Grand colonnade, Palmyra, photo: Colleen Morgan, CC BY 2.0

City of Palms

Built around an oasis in the Syrian desert, Tadmur or Palmyra, “city of palms,” was one of the most important trade and cultural centers of the ancient world. Palmyra had a distinctive local culture that was incorporated into the Roman Empire in the first century C.E. More than two centuries later, the city gained independence from Rome and under its famous Queen Zenobia established the Palmyrene empire which annexed much of the eastern part of the Roman Empire.

Palmyrene Empire at its greatest extent in 271 C.E., CC BY-SA 4.0 (source)

Palmyra stands at the crossroads of civilizations—along the silk routes where merchants traveled between Europe and Asia.

The art and architecture of the city is a perfect portrait of the fertile crescent with its amazing blend of cultures and traditions. A dynamic culture and a land of inherent pluralism owing to its Mesopotamian, Levantine, Semitic, Greco- Roman, Persian, and Islamic heritage.

Palmyra was inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1980 and has a particular place in the Syrian historic consciousness. Syrians take pride in the once-great merchant city that influenced and ultimately defied the power of Rome.

Palmyra’s grand colonnade (above) is a 1,100m long Roman period street that connects a temple to the god Bel with the area known as the Camp of Diocletian. Other archaeological remains in the ancient city of Palmyra include an agora, theatre (below), urban quarters, and other temples that comprise what is generally considered by scholars to be the finest example of surviving Roman architecture in the Eastern Mediterranean.

The Fakhr-al-Din al-Ma’ani Castle with a view of Palmyra, photo: Wurzelgnohm (public domain)

Also within the archaeological zone of Palmyra stands the Fakhr-al-Din al-Ma’ani Castle. This heavy fortification dates to the 13th century and offers a spectacular view of the site.

Tombs

The affluent residents of ancient Palmyra built elaborate tombs outside the city walls, adorned with portraits of citizens. Bust sculptures of wealthy patrons from Palmyra, dating to the 1st and 2nd centuries C.E., demonstrate the complexity and richness of Palmyrene identity. These busts combine Roman sculptural elements and local stylistic elements. Some of these portraits were accompanied by inscriptions in the Palmyrene dialect of Aramaic.

The Syrian civil war

Both the modern town and ancient city of Palmyra were caught in the crossfire of the Syrian civil war beginning in early 2013. Then in 2014, military forces from the regime of Bashar al-Assad (president of Syria) fortified the site, further damaging the ruins.

In 2015, ISIS overran Palmyra, and committed barbaric and monstrous assaults on the people, cultural monuments, and artifacts of the city. The destruction of Palmyra’s magnificent monuments provoked an international outcry and prompted media attention.

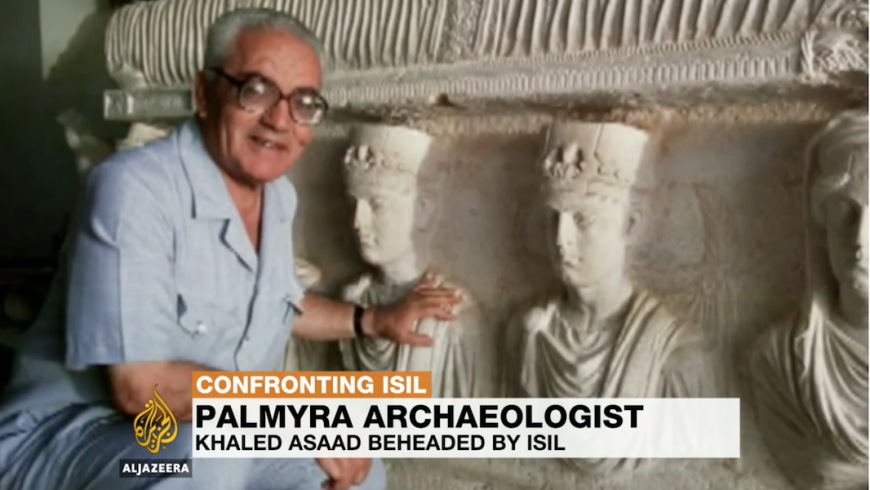

ISIS began by executing Khaled Al-Ass’ad, the former Director of Antiquities at Palmyra, a devoted and outstanding archeologist who loved Palmyra like no one else. Following this horrific execution, ISIS began to destroy many of the most famous ruins—the Bel and Baalshamin temples, the tower tombs, the monumental arch and standing columns in addition to plundering the Palmyra Museum and destroying a large number of sculptures and artifacts left there.

In March 2016, the Assad forces (backed by the Russian military) recaptured Palmyra and immediately started building a Russian military base within the World Heritage Site. ISIS recaptured Palmyra in early December 2016 and destroyed the tetrapylon and damaged the theater. The Assad regime forces managed to take Palmyra back in March 2017.

Palmyra theater proscenium, 2nd century C.E. (photo: Bernard Gagnon, CC BY-SA 3.0), before destruction by ISIS in 2015

Looting and propoganda in Palmyra

The ancient site also witnessed extensive looting and many Palmyrene artifacts appeared on the antiquities market or were captured by Lebanese and Turkish customs officials. Looting started in the fall of 2011, when the Assad regime lost control of the town. Then, during the ISIS occupation, the so-called Diwan al Rikaz office was established which gave digging permits in exchange for paying a tax. The permit was for non-figurative objects only (presumably objects with human figures were to be destroyed by ISIS fighters). However, the looters are believed to have handed over only unsellable figurative objects to the Diwan al Rikaz, hiding from ISIS artifacts in good condition that could be sold to dealers.

Throughout these episodes where control shifted between the forces of the Assad regime and ISIS, Palmyra, its monuments, and artifacts were used to reinforce the appalling political propaganda being disseminated. In late 2015, ISIS used the ancient theater to stage dramatic executions for circulation on social media. Soon after, the Russian military staged a musical concert at the same theater to promote an image of a civilized Russian savior, only to leave ISIS to capture the city nine months later with little fighting. Syrian cultural heritage, including that of Palmyra, should play a reconciling and unifying role in post-conflict Syria. Syrian cultural heritage should not be used in the political or sectarian agenda of the groups fighting in the Syrian conflict.

Triumphal arch, Palmyra, destroyed by ISIS in 2015 (photo, CC BY-SA 2.5)

Restoring Palmyra

In May 2016, when ISIS was first driven from Palmyra, there were numerous calls, led by UNESCO, to begin the work of restoring the ancient city despite the fragile security conditions. Millions of Syrians are still suffering from the consequences of the bloody war. Among them are the people of Palmyra, who continue to experience grave risks, including detention by the Assad government, and the destruction of their homes and heritage.

When the day for the reconstruction of Palmyra comes—after the conflict is over—it will require a period of reflection about what should be reconstructed, how it should be rebuilt, and how the recent events of the war and occupation by ISIS should be memorialized—if at all. This discussion must be undertaken by Syrians on all sides of the conflict, and not decided for Syria by international organizations.

Model of the trimphal arch at Palmyra (built to 1/3 scale), created by the Institute for Digital Archaeology, Oxford University (photo © Stephen Richards, CC-BY-SA 2.0)

The question of 3D models

A new development in the documentation of heritage sites has been the application of new technologies to create 3D online libraries of the world’s important cultural heritage sites and a number of projects have recently worked to create a 3D models of Palmyra’s lost monuments. The Institute for Digital Archaeology at the University of Oxford has created a 3D model of the destroyed triumphal arch using structure-from-motion photogrammetry.

The 3-D printed arch was displayed in London, New York, and other cities, prompting a debate about the purpose of such reconstructions and their display—especially given that the reproduction failed to capture the authenticity of the original structure and that the project revealed a disconnection with the Syrian people and the inhabitants of Palmyra, who have lived alongside these monuments for many generations.

Additional resources:

The site of Palmyra on UNESCO’s World Heritage List

Should we 3D print a new Palmyra?, The Conversation, March 31, 2016.

About the Silk Road (from UNESCO)

Institute for Digital Archaeology, Oxford University and the Triumphal Arch at Palmyra

[0:00] [music]

Dr. Steven Zucker: [0:05] We’re on the second floor of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, looking at tomb portraits that come from the ancient city of Palmyra, in what is now Syria. This city, which is on the edge of the desert, is an oasis, and was this point in the caravan route between the Roman Empire and Asia.

[0:25] They controlled this critical link in what we call the Silk [Roads] that linked the Mediterranean region with Central Asia as far as China. Palmyra in 2015 and 2017 was overrun by ISIS.

Dr. Salaam al-Kuntar: [0:41] ISIS had to mobilize whatever resources they had. These were resources they could use to draw media attention. That was a unique opportunity at Palmyra because for them, the whole event is the video. ISIS marched to the site over five days. And the US military and its allies were holding major operations in Syria against ISIS at the time.

[1:05] Many American archaeologists and international archaeologists appeal[ed] to the protection of the site of Palmyra because they saw that ISIS was marching there, but there was no response whatsoever. So there was no intention of protecting the site.

[1:19] It is shameful that in the 21st century, with all the appreciation of cultural heritage and art, it still happened to a World Heritage site. Then we start asking ourselves, what is the meaning of a World Heritage site if that site cannot be protected?

Dr. Zucker: [1:36] In a sense, there was a double failure. On the one hand, we allowed ISIS to take the city hostage, to use it for its own propaganda purposes, but in a more permanent sense, the monuments of Palmyra suffered irreparable harm. This was an event that possibly could have been stopped if the US Army, if the Assad regime, had tried to turn ISIS’s path away from this treasured archaeological site.

Dr. al-Kuntar: [1:59] These wars in the Middle East that show you how even in the 21st century we have little appreciation of culture. Culture comes at the bottom of priorities of all governments.

Dr. Zucker: [2:10] But it is this heritage that makes up people’s identity, their sense of self, and so I can’t imagine something more important in the long run.

Dr. al-Kuntar: [2:20] People underestimate how much damage to cultural heritage affects people and their identity and self-awareness. If you think about the trauma that people go through, it’s not only the very personal story of killing and torture and forced migration but it’s also the destruction of the beloved places, the loss of the homeland with all this cultural heritage, that [which] makes a homeland a homeland.

Dr. Zucker: [2:47] We’re looking at six relief carvings that originally functioned as closing stones for tombs that were placed within towers just on the outside of the city of Palmyra. These six are of many thousands that existed and that have been collected since the 18th century. ISIS didn’t just destroy objects, they also looted and raised money through their illicit sale.

Dr. al-Kuntar: [3:10] There were looters who already went in to take advantage of the instability and lack of security. What ISIS did is regulate the looting and considered antiquities as resources like oil.

[3:26] They said, “OK, whatever that is not a figurative artifact, you can sell it and we will tax you.” But of course, the looters are finding these busts and figurines. So they would hide those from ISIS and then sell them off-market. It was a very ad hoc situation.

Dr. Zucker: [3:44] The tower tombs met a tragic fate under ISIS in 2015. They targeted the most intact and the largest of the tombs, destroying seven of them.

Dr. al-Kuntar: [3:53] They did blow them up. They did them one by one. Some of them, they publicized it. Others, we found out through satellite imagery.

Dr. Zucker: [4:01] The event that upset the archaeological community most deeply was the murder of the longtime director of antiquities of the site, a man who had given his life to understanding and protecting the antiquities of Palmyra.

Dr. al-Kuntar: [4:10] Khalid al-Assad, he’s a Syrian archaeologist from Palmyra. He studied Palmyra very deeply. No one knows Palmyra the way he knows. He knows every stone. He refused to leave, even though the threats of ISIS coming. He was executed in a horrific way.

Dr. Zucker: [4:32] This crisis has not ended. But as we begin to look towards the future, the archaeological community, the community concerned with historical preservation, and of course most centrally the Syrian people themselves, need to start grappling with how do we retrieve ancient history while respecting the loss of life that has happened recently.

Dr. al-Kuntar: [4:58] We need to look back and document even the destruction event itself. It’s not an easy process. International organizations and UNESCO should not take decisions on behalf of the people of Palmyra who are still refugees.

[5:19] We want to learn from the Syrian civil war and the destruction. How are we going to tell the ancient story and the destruction story? Any visitors to the site in the future, they need to see it. The same way as lots of the atrocities of Nazi Germany, it is still there to see and learn from.

[5:56] We need to carefully think about how we’re going to tell the story of this modern event, not only go back and erase any traces of destruction and build the site back like nothing happened. This is important for people to know and learn from.

[6:02] [music]