Forum of Pompeii, looking toward Mount Vesuvius (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 C.E. destroyed and largely buried the cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum and other sites in southern Italy under ash and rock. The rediscovery of these sites in the modern era is as fascinating as the cities themselves and provides a window onto the history of both art history and archaeology.

The eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 C.E. destroyed and largely buried the cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum and other sites in southern Italy under ash and rock. The rediscovery of these sites in the modern era is as fascinating as the cities themselves and provides a window onto the history of both art history and archaeology.

Pompeii today

Today the site of Pompeii is open to tourists from all over the world. Major projects in survey, excavation, and preservation are supervised by Italian and American universities as well as ones from Britain, Sweden, and Japan. Currently, the major concern at Pompeii is conservation—officials must deal with the intersection of increased tourism, the deterioration of buildings to a sometimes dangerous state, and shrinking funding for archaeological and art historical monuments. The 250-year-long story of the unearthing of Pompeii, Herculaneum, and the other sites destroyed by Vesuvius in 79 C.E. has always been one of shifting priorities and methodologies, yet always in recognition of the special status of this archaeological zone.

Hidden for centuries?

The popular understanding of the immediate aftermath of the eruption of Mt. Vesuvius is that Pompeii, Herculaneum, and sites like Oplontis and Stabiae, lay buried under ash and volcanic material—completely sealed off from human intervention, undisturbed and hidden for centuries. Archaeological and geological evidence, however, indicates that there were rescue operations soon after the eruption (see, for example, the tunnels dug through the House of the Menander) and that some parts of these cities remained visible for some time (the forum colonnade at Pompeii was not completely covered). Throughout the Middle Ages, Pompeii was entirely deserted, yet locals referred to the area as La Cività (“the settlement”), perhaps informed by folk memory of the city’s existence.

Sebastian Pether, The Eruption of Vesuvius, 1825, oil on wood panel (The Nelson Atkins Museum of Art). Vesuvius erupted again in the late 1700s and early 1800s. Though Pether travelled to Italy to paint the volcano, here he depicted the one eyewitness account of the eruption in 79 C.E. by Pliny the Younger.

Excavations begin

While Renaissance scholars must have been aware of Pompeii and its destruction through various ancient written sources, the first “archaeologist” in the area was apparently unimpressed with his discoveries. From 1594-1600, the architect Domenico Fontana worked on new constructions in the area and accidentally excavated a number of wall paintings, inscriptions, and architectural blocks while digging a canal. No one undertook follow-up explorations for nearly a century and a half, despite the general interest in antiquity and rudimentary archaeology at the time.

This bronze was probably the most celebrated sculpture discovered at Herculaneum and Pompeii in the eighteenth century. It was excavated in 1759 at the Villa of the Papyri in Herculaneum and kept in the royal palace at Portici. Seated Mercury (also known as Hermes at Rest), Roman copy of an ancient Greek bronze, 105 cm (Museo Nazionale, Naples, photo: Marie-Lan Nguyen, CC BY 2.5)

The eighteenth century saw the first large-scale excavations in this region, motivated by the desire to collect works of ancient art as much as by a scientific curiosity about the past. Further incidental discoveries in the early decades of the 1700s prompted Charles VII, King of Spain, Naples, and Sicily, to commission a survey of the area of Herculaneum.

Official excavation began in October 1738, under the supervision of Rocque Joaquin de Alcubierre, a military engineer who tunneled through the practically petrified volcanic material to find remains of Herculaneum more than 20 meters under the surface. This dangerous work (tunnel collapse and toxic gases were a constant threat), yielded wall paintings, life-size sculpture in both bronze and marble, and papyrus scrolls from the Villa of the Papyri. Many of these recovered works went to decorate the palace of the king. Archaeology was still in its infancy as a practical field of study at this time, and was often more about “treasure-hunting” than careful research or documentation.

A Swiss engineer, Karl Jakob Weber, took over the excavation of Herculaneum from de Alcubierre in 1750 and brought more cautious methods to the site. Weber’s practices of recording the findspots of important objects in three dimensions and making detailed plans of architectural remains laid the foundations for the indispensable procedures of modern archaeology. De Alcubierre shifted his focus to Pompeii, which had just been (re)discovered in 1748. Among the early excavations there were the amphitheater and an inscription confirming the town’s name: REI PUBLICAE POMPEIANORUM. With finds from Herculaneum and Pompeii increasing exponentially, King Charles inaugurated a Royal Academy in Naples in 1755, dedicated to mapping the sites and publishing significant discoveries.

The new fields of archaeology and art history and the building of a royal collection

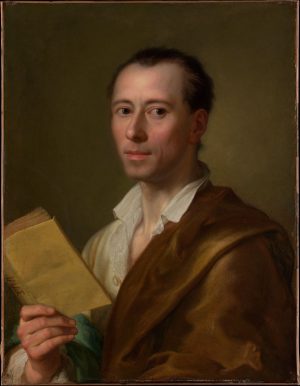

Anton Raphael Mengs, Johann Joachim Winckelmann, c. 1777, oil on canvas, 63.5 x 49.2 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

The field of art history was emerging concurrently with these early excavations and naturally sites like Pompeii and Herculaneum were of great interest to the man who coined the term “history of art”—the German scholar Johann Joachim Winckelmann. His reports on the finds from this area fanned the flames of European fervor for classical antiquity (ancient Greece and Rome), and Grand Tour travelers from Britain and elsewhere beat a path to Pompeii and Herculaneum in the late 18th century.

Although Winckelmann was most concerned with categorizing Greek and Roman sculpture, he was also keenly interested in the new field of archaeology: he knew enough of this science to criticize the secrecy and aggressive methods of de Alcubierre, an action that got Winckelmann effectively banned from Pompeii.

It was actually King Charles’s desire (and that of his successor Ferdinand) for beautiful artifacts that closed much of the excavations off to outside scholars, with most of the important finds going directly into the private royal collection. The king also enacted laws forbidding the export of antiquities from the Kingdom of Naples. Even the publication of the monumental Le antichità di Ercolano esposte (The antiquities of Herculaneum displayed, 1757-92) was tightly controlled and the illustrated volumes were only selectively presented to other European monarchs by the king himself.

Preservation and access

With the arrival of Francesco la Vega as director of excavations in Pompeii in 1780, the conservation of buildings and artifacts became a priority. Francesco, and his brother Pietro after him, removed valuable artifacts to the new Naples Museum, where they joined other pieces from the royal collection. Francesco la Vega also embraced Weber’s concerns for recording three-dimensional contexts, and it was under his leadership that the Triangular Forum, the Temple of Isis, and the theater district were uncovered. However, like many archaeologists at Pompeii, la Vega struggled with a significant conflict: a desire to preserve the rare ancient wall paintings in situ while maintaining the site as a singular opportunity for visiting an ancient Roman city whose walls and roofs still stood. Paintings and buildings were left open to both treasure-hungry visitors and the elements, resulting in both natural and man-made deterioration at Pompeii.

Temple of Isis, Pompeii (photo: Amphipolis, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Perhaps no archaeologist had such a significant influence on the exploration of Pompeii as Giuseppe Fiorelli. He was superintendent of Pompeii for twelve years (1863-1875) during a supremely patriotic moment after the unification of Italy in 1860 when the country’s archaeological heritage was a tremendous source of pride. Fiorelli did not meet his goal of uncovering the entire city—only about one third of the Pompeii was excavated—but he accomplished other important tasks and brought new techniques to the site.

Opening the site to visitors and the first entrance fee

Fiorelli systematically organized the site by dividing it into nine regions and providing a system of “addresses” for insulae (city blocks) and doorways. In a dramatic shift from the restrictive 18th-century approach to tourism in Pompeii, Fiorelli opened the site up to visitors from all over the world—and he also introduced the first entrance fee. His exhaustive reports on the excavations kept scholars apprised of developments on the site.

Fiorelli is best known for his use of plaster casting techniques which permitted a kind of preservation of otherwise ephemeral archaeological finds like wood and human remains. By pouring plaster into voids in the ash left by decomposed organic material, Fiorelli’s casts gave form to things like wooden doors, window frames, furniture, and of course the victims of the eruption of Mt. Vesuvius. The casts of human remains—including adults and children, not to mention a pet dog—remind visitors to this day that the great gift of Pompeii’s archaeology came at tremendous cost (as many as 2,000 people lost their lives).

Plaster cast of a body, Forum storage, Pompeii (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Archaeological investigation continues—as an international project

In the late 19th century, exploration of Pompeii and Herculaneum became a more international project. The British diplomat Sir William Hamilton had already published studies of volcanic activity and painted pottery from the region in the late 18th century. German scholars of the 1800s studied inscriptions (Theodor Mommsen), outlined the city plan (Heinrich Nissen), and created typologies of wall painting (Wolfgang Helbig). August Mau’s thorough categorization of the Four Styles of Pompeian frescoes, published in 1882, remains the basis for wall painting studies today. The late 19th century also saw the excavation and restoration of two of Pompeii’s most spectacular houses—the House of the Vettii and the House of the Silver Wedding.

House of the Vettii, Pompeii, Italy, Imperial Roman, c. second century B.C.E., rebuilt 62-79 C.E., cut stone and fresco (photo: Peter Stewart, CC BY-NC 2.0)

Pompeii in the 20th century: interruptions to archaeological work and bombing

The 20th century continued to be a very productive time at Pompeii for Italian archaeologists, even though work was interrupted by world events. Vittorio Spinazzola (director, 1911-1923) opened a massive excavation campaign along the Via dell’Abbondanza. His work not only uncovered important residences like the House of Octavius Quartio, but also contributed to our understanding of upper floors of Pompeian buildings. Spinazzola’s work was interrupted by the outbreak of World War I and he was forced to step down from his position by Italy’s Fascist government. Amedeo Maiuri was the director of excavations from 1923-1962 and oversaw the discovery of the Villa of Mysteries and the House of the Menander.

Although work was stopped again at Pompeii during the Second World War, Maiuri succeeded in broadening the excavations to the extent seen today: about two-thirds to three-quarters of the city’s final phase has been uncovered. Maiuri was also concerned with pre-Roman Pompeii, opening excavations below the most recent layer; he also undertook extensive restoration and conservation work.

A terrible moment for Pompeii occurred in 1943 when the Allies dropped more than 150 bombs on the site, believing Germans were hiding soldiers and munitions among the ruins. At least one bomb fell on the on-site museum, destroying some of the more interesting artifacts discovered by that time.

Nevertheless, thanks to the efforts of the many archaeologists and researchers who have worked to uncover the remains of Pompeii and Herculaneum over the last three centuries, today we can again walk the streets of these fascinating ancient Roman towns.

Additional resources:

The eruption story from The British Museum

Dr. Damian Robinson, “The Elite House and Commercial Life along the Via dell’Abbondanza”

Dr. John J. Dobbins, “Public Space and via dell’Abbondanza”

Archaeological Areas of Pompei, Herculaneum and Torre Annunziata (UNESCO)

Roman domestic architecture – the insula