Major threats to cultural heritage come in two forms: destruction during military conflict and the looting of sites and collections. Both in antiquity and in contemporary times, we see these destructive activities often going hand in hand, but we also see a consistent development toward recognition that such cultural remains should be protected.

Toward a recognition that cultural heritage should be protected

In the second century B.C.E., the ancient Roman author Polybius criticized the Roman plunder of Greek sanctuaries on Sicily. A century later, the Roman orator, Cicero, prosecuted the Roman governor of Sicily, Gaius Verres, for excessive looting of Sicilian cities. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the Dutch jurist Hugo Grotius and the international legal theorist Emmerich de Vattel established principles stating that, as works of art were not useful to the military effort, they should be protected.

Greek Temple of Apollo, Syracuse, Sicily (photo: Allie_Caulfield, CC BY 2.0)

During the Napoleonic Wars of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, the French looted artworks from throughout Europe as well as from Egypt and brought them to Paris, which was to be recreated as the “new Rome.” With the defeat of Napoleon, the British leaders (the Duke of Wellington and Viscount Castlereagh) not only declined to take these collections for Britain but decreed that the French should return those artworks taken from other European nations. Despite this, only about half of the works looted by Napoleon—and none of those taken from non-Europeans—were returned.

Phidias, East Pediment Sculpture for the Parthenon (a.k.a. the “Elgin Marbles”) (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

During this same time period, the British Lord Elgin, at that time ambassador to the Ottoman Empire, removed sculptures and architectural elements from the Parthenon and other structures in Athens and brought them to London, where they were later purchased by the British Museum.

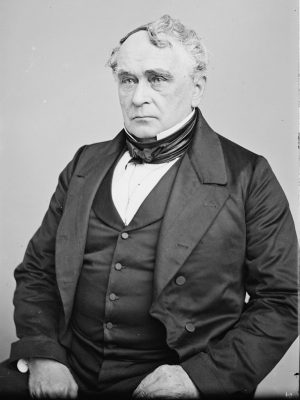

Francis Lieber, c. 1855-65 (Brady-Handy Collection, Library of Congress)

The Lieber Code

In 1863, during the American Civil War, the first military code of conduct was written at the request of President Abraham Lincoln by Francis Lieber, who had been present as a young soldier at the Battle of Waterloo. Lieber later studied the classics and then moved to the United States, where he became a professor of history. Known as the Lieber Code, it addressed the same two threats discussed above: destruction and looting. Lieber wrote that structures devoted to religion or education and museums of the fine arts and science should not be destroyed during armed conflict and “classical works of art, libraries, scientific collections or precious instruments…must be secured against all avoidable injury even when they are contained in fortified places whilst besieged or bombarded.” He added that such objects shall not “be sold or given away…nor shall they ever be privately appropriated, or wantonly destroyed or injured.”

First international conventions

The Hague Conventions and Regulations of 1899 and 1907 were the first international instruments to codify rules on the conduct of warfare. Influenced by the Lieber Code, they ingrained these same concepts of protection into international law. These two Hague Conventions were the governing instruments during both World Wars. While these Conventions did not prevent large-scale theft and destruction of cultural objects and structures—particularly during the Second World War—they served as the basis for prosecution and punishment of those who violated their principles.

Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives (MFAA) Officer James Rorimer supervises U.S. soldiers recovering looted paintings from Neuschwanstein Castle in Germany during World War II, April-May, 1945 (The National Archives)

The Hague Convention after WWII

At the end of the Second World War, in response to the humanitarian and cultural devastation in Europe caused by the Nazis, the international community promulgated a series of international humanitarian conventions. Cultural property protection was now separated into its own distinct convention: the 1954 Hague Convention on the Protection of Cultural Property during Armed Conflict and its First Protocol.

Article 1 of the Convention defines cultural property as

movable or immovable property of great importance to the cultural heritage of every people, such as monuments of architecture, art or history, whether religious or secular; archaeological sites; groups of buildings which, as a whole, are of historical or artistic interest; works of art; manuscripts, books and other objects of artistic, historical or archaeological interest; as well as scientific collections and important collections of books or archives…; buildings whose main and effective purpose is to preserve or exhibit the movable cultural property…such as museums, large libraries and depositories of archives, and refuges intended to shelter, in the event of armed conflict, the movable cultural property.…

The two core principles of the Convention are safeguarding of and respect for cultural property.

The first obligation of Parties to the Convention is to “prepare in time of peace for the safeguarding of cultural property situated within their own territory” by taking whatever steps they consider appropriate to protect their cultural property from the foreseeable effects of warfare (Article 3).

The obligation of respect (Article 4) prohibits the use of cultural property for strategic or military purposes if doing so would expose the property to harm during warfare. In addition, States must not target cultural sites and monuments. However, this obligation is subject to a significant exception “in cases where military necessity imperatively requires such a waiver” (Article 4, para. 2). In other words, if attacking a cultural site or monument is necessary to achieve an imperative military goal, then military necessity supersedes, and the protections for cultural property of this article are lost. Unfortunately, the Convention does not define “military necessity,” and some nations have criticized this exception since a fairly low level of necessity could result in destruction or damage to cultural sites and monuments.

Article 4 also imposes an obligation on a Party to the Convention “to prohibit, prevent and, if necessary, put a stop to any form of theft, pillage or misappropriation of, and any acts of vandalism directed against, cultural property” (Article 4, para. 3).

The First Protocol to the 1954 Hague Convention also addresses the subject of movable cultural property. However, it does so only under very narrow circumstances of illegal removal of cultural objects from occupied territory and the voluntary deposit of cultural objects by one State in another State for the purpose of safekeeping.

15th Session of the Assembly of State Parties of the International Criminal Court at the World Forum in The Hague, Netherlands (photo: Eloïse Bollack, Coalition for the ICC, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Second Hague Protocol and the Rome Statute

The Second Protocol was adopted in 1999 to clarify some of the provisions of the Hague Convention. For example, it narrows the definition of military necessity and requires States to adopt criminal measures for those who intentionally violate the Convention’s provisions. Other international legal instruments address the protection of cultural property, most particularly the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, which classifies intentional destruction of cultural property as a war crime.

An increasing loss

In the post-Second World War period, the appetite of the international art market for works of art, including archaeological objects, grew along with the increase in wealth of the European and North American countries. At the same time, the increasing use of scientific methodologies (including stratigraphic retrieval and scientific analyses) meant that greater quantities of information could be recovered from the proper excavation of sites. As a result, looting caused an increasing loss to our knowledge and understanding of the past. Finally, with the end of colonialism in much of the world, particularly Africa and Asia, the new countries sought legal means to conserve at home what remained of their heritage, after so much had been lost to the colonial powers.

1970 UNESCO Convention

Sparked in particular by the work of Professor Clemency Coggins, who brought world attention to the destruction of Maya architectural and monumental sculptural remains in Central America, the world community under the leadership of UNESCO drafted the 1970 UNESCO Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property to confront the illegal trade in art works, antiquities, and ethnographic objects. This Convention makes illicit the import, export, and transfer of cultural property contrary to its provisions. Some countries, such as Germany, Canada, and Australia, prohibit the import of any illegally exported cultural objects. Other countries, such as the United States and Switzerland, prohibit the import of illegally exported archaeological and ethnological materials, as long as there is an additional bilateral agreement in place between themselves and the country of origin.

Temple of Bel, Palmyra, Syria, photographed in 2007; destroyed in 2015 (photo: Erik Albers, public domain)

New resolutions for modern warfare

Both the 2003 Gulf War and the civil war in Syria (2011-present) created opportunities for large-scale destruction and looting of archaeological sites. During the conflict in Syria, Daesh intentionally destroyed ancient structures at the sites of Palmyra in Syria, at Nineveh, Nimrud, and other Neo-Assyrian sites in Iraq, and objects in the Mosul Museum in Iraq. The looting of archaeological sites helped to fund the terrorism and military conflict of Daesh and possibly of the Assad regime in Syria.

In response, the United Nations Security Council enacted a series of Resolutions calling on all member States to prohibit the import of and trade in undocumented archaeological and other cultural materials from Iraq and Syria. These Resolutions have established a new standard for controlling the market for looted archaeological objects, at least within the context of armed conflict. These events have also brought the negative effects of looting and destruction of cultural heritage to the attention of the world community and encouraged countries to take further steps to prevent this destruction.

Additional Resources:

Summary of recent cultural heritage protections (UNESCO)

Kevin Chamberlain, War and Cultural Heritage: A Commentary on the Hague Convention 1954 and its Two Protocols (2nd ed., Builth Wells, UK: Institute of Art and Law, 2013).

C.C. Coggins, “Illicit Traffic of Pre-Columbian Antiquities,” Art Journal 29 (1969), pp. 94-114.

Patty Gerstenblith, Art, Cultural Heritage and the Law (3rd ed., Cary, N.C.: Carolina Academic Press, 2012).

Patty Gerstenblith, “The Destruction of Cultural Heritage: A Crime against Property or a Crime against People?,” John Marshall Review Intellectual Property Law 15 (2016), pp. 336-93.

Patty Gerstenblith and C.R. Smith, “Looting and the Antiquities Market,” Oxford Bibliographies in Classics, edited by Dee Clayman (New York: Oxford University Press, 2015).

M.P. Kouroupas, “Preservation of Cultural Heritage: A Tool of International Public Diplomacy,” in Cultural Heritage Issues: The Legacy of Conquest, Colonization, and Commerce, edited by James A.R. Nafziger and Ann M. Nicgorski (Leiden: Martinus Nijhoff, 2010), pp. 325-334.

K.E. Meyer, The Plundered Past (New York: Athenaeum, 1977).

M.M. Miles, Art As Plunder: The Ancient Origins of the Debate about Cultural Property (Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 2008).

P.J. O’Keefe, Protecting Cultural Objects: Before and After 1970 (Builth Wells, UK: Institute of Art and Law 2017).

J.F. Witt, Lincoln’s Code: The Laws of War in American History (New York: Free Press, 2012).