Nicolas Poussin, The Holy Family on the Steps, 1648, oil on canvas, 73.3 x 105.8 cm (Cleveland Museum of Art; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

The sheer repetition of certain subjects can tire even the most ardent student of art history. By 1648 when Nicolas Poussin painted The Holy Family on the Steps countless renditions of the Christian scene of the Virgin Mary, Saint Joseph, and the Christ Child produced over many centuries already existed. 17th-century viewers expected interesting compositions from artists, but also artworks that respected the existing tradition.

Poussin has placed the Holy Family in the foreground of an outdoor setting. The Virgin’s cousin, Saint Elizabeth wearing yellow, sits behind her son, Saint John the Baptist, who is also Christ’s cousin. The younger Virgin Mary holds Christ on her lap. Behind them, Saint Joseph, the Virgin’s husband, sits in shadow wielding an architect’s compass. Poussin has not described the surrounding buildings in much detail, but we can surmise from the columns and Corinthian capitals that their location is classical. No wind disturbs clouds in the blue sky or rustles the leaves of the orange tree behind the fountain. Only the water’s splash and the small movements of the figures enliven the stony environment.

Nicolas Poussin, The Holy Family on the Steps, 1648, oil on canvas, 73.3 x 105.8 cm (Cleveland Museum of Art; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Find the symbol

In Poussin’s oeuvre alone, there are more than a dozen Holy Family compositions and nearly 30 iterations of the subject. [1] For Holy Family on the Steps, Poussin deployed familiar iconography loaded with symbolic meaning and replete with art historical references. Less a work intended to evoke intense emotion from the viewer, Poussin’s Holy Family keeps a commonplace subject engaging by giving the viewer a plethora of references to identify. The painting becomes a site for engagement.

Viewing paintings in early modern Europe was often a social activity among Poussin’s learned and wealthy client base (the patron of Holy Family on the Steps is believed to be Nicolas Hennequin de Fresne, the Baron d’Ecquevilly). While regarding a work of art together, people could contribute to the conversation by listing the symbolic meanings and allusions they identified. Finding associations and related meanings attested to the beholder’s erudition and cleverness.

Because of the iconographic tradition long established in European Christian art, Poussin could expect viewers to immediately recognize the subject of the painting as the Christian Holy Family: Mary, Joseph, and Jesus Christ. Poussin could also assume that the majority of beholders would be able to identify the second child as Saint John the Baptist and the older woman behind him as his mother, Saint Elizabeth. Their presence makes this an extended Holy Family scene, as it were, and enhances the symbolic meaning of the painting.

Saint John the Baptist handing an apple to the Christ Child (detail), Nicolas Poussin, The Holy Family on the Steps, 1648, oil on canvas, 73.3 x 105.8 cm (Cleveland Museum of Art; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Salvation foretold

Between their two mothers, a precociously dynamic Christ Child reaches towards his cousin Saint John the Baptist, who offers him an apple. The sweet interaction reads both as youthful play and simultaneously carries symbolic meaning. In an episode known as The Visitation, when Mary and Elizabeth meet while both pregnant, Elizabeth says the babe in her womb, the unborn Saint John the Baptist “leaped” recognizing The Virgin’s blessed pregnancy. [2] It was an early recognition of Christ’s divinity from Saint John, who would later baptize Christ as an adult, an episode that revealed Christ’s divine nature.

The apple recalls the fruit the first humans, Adam and Eve, stole from the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil in the Old Testament Book of Genesis. When they ate from the apple, according to Christian thought, they committed the Original Sin. In Catholic thought, all humans, following Adam and Eve, are born with Original Sin, condemning all humans. In Christianity, it is Christ’s eventual Crucifixion that brings humans a chance for redemption in the afterlife.

So, when Poussin’s Christ Child reaches for the apple proffered to him by Saint John the Baptist, he prefigures his Crucifixion.

The young Christ accepts humanity’s Original Sin and his future sacrifice. In this way, Christ was understood theologically as a “New Adam” and the Virgin Mary as a “New Eve.” The redemption of mankind is foretold through symbolism at the center of Poussin’s painting.

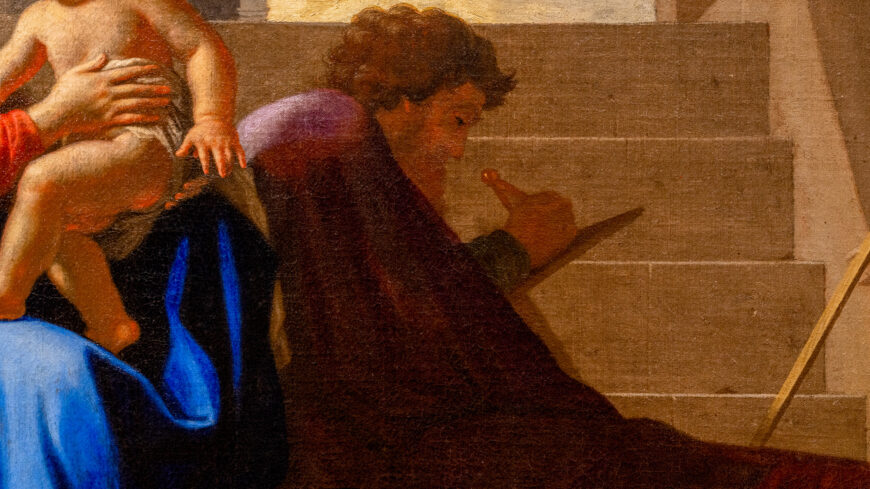

Joseph (detail), Nicolas Poussin, The Holy Family on the Steps, 1648, oil on canvas, 73.3 x 105.8 cm (Cleveland Museum of Art; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Saint Joseph holding an architect’s compass alludes to God’s role designing and planning world order. As Christ’s stepfather, Joseph, who worked as a carpenter, allegorically parallels God the Father. [3] Christ’s salvation of humanity was preordained.

Nicolas Poussin, The Holy Family on the Steps, 1648, oil on canvas, 73.3 x 105.8 cm (Cleveland Museum of Art; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

The Virgin Mary’s many meanings

The importance of the figures is compositionally conveyed by the low horizon line which gives the impression of looking up at the holy figures from below. In the figural composition, the Virgin’s head forms the apex of a pyramid, marking her again as of special significance. In addition to her compositional prominence, Poussin has added many symbolic meanings.

As is iconographically standard in European Christian art, the Virgin Mary wears clothing in the colors of red, symbolic of caritas, the virtue of charity, and blue, indicating divine wisdom. Though monumental in form, the Virgin sits on the ground, an iconographic type known as a “Madonna of Humility,” adding humbleness to the virtues Poussin communicates through compositional choices.

By positioning the Virgin in a seated pose with her foot planted firmly on the ground, Poussin indicates metaphorical meanings ascribed to the Virgin Mary. Her solid supportive stance invokes the common metaphor of Mary as ecclesia, that is as the Church itself, which also supports Christ.

Poussin was not finished. To the above symbolic meanings, the artist added the Virgin as a “throne of Solomon.” The Virgin acts as a throne by holding Christ on her lap. Christ, the divine king, embodies wisdom in Catholicism. In Christian thinking, Christ was prefigured by Solomon, the Old Testament king noted for his wisdom. Therefore, the Virgin became known as the sedes sapientiae, the seat of wisdom, even as the Virgin Mary herself also embodied wisdom.

Vase with greenery (detail), Nicolas Poussin, The Holy Family on the Steps, 1648, oil on canvas, 73.3 x 105.8 cm (Cleveland Museum of Art; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

The foliage also refers to the Madonna’s virtues. The large vase with greenery conveys her role as she who brings everlasting life into the world via Christ. The fountain is associated with baptism and its resulting salvation. Its clear water supplied an easy metaphor for the Virgin’s purity. Learned viewers might also associate the fountain with the “well of living water,” a Biblical verse associated with the Virgin Mary. [4]

Fountain with water (detail), Nicolas Poussin, The Holy Family on the Steps, 1648, oil on canvas, 73.3 x 105.8 cm (Cleveland Museum of Art; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Viewers could also spot references to the Virgin Mary through the architectural design. Though the figures sit outdoors, no entrance or exit can be seen in Poussin’s painting. The stony environs form a hortus conclusus, a closed garden, a metaphor for the Madonna’s virginity, her untouched purity.

The prominent staircase behind Mary alludes to her role as the scala coelestis, the staircase to heaven. As scala coelestis, the Virgin was the path by which God descended to earth in the form of Jesus Christ as well as the route for humanity to ascend to heaven. In Catholicism, worshippers often prayed to the Virgin Mary asking her to intercede on their behalf with God the Father or Jesus Christ.

Left: Fruit basket (detail), Nicolas Poussin, The Holy Family on the Steps, 1648, oil on canvas, 73.3 x 105.8 cm (Cleveland Museum of Art; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0); right: Caravaggio, Basket of Fruit, c. 1595–96, oil on canvas, 67.5 x 54.5 cm (Pinacoteca Ambrosiana, Milan)

Allusions to art history

The Holy Family on the Steps treats savvy viewers to not just theological symbolism, but also a bevy of art historical allusions ready to be identified. Though Caravaggio and Poussin were often considered artistic opposites, Poussin quoted the Italian painter’s wicker basket filled with abundant fruit. He has even placed it, as Caravaggio did, anxiously hovering over an edge like in one of Caravaggio’s still life paintings and in The Supper at Emmaus.

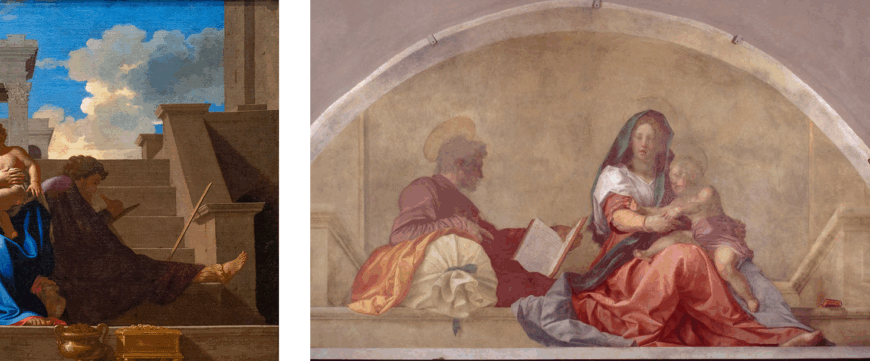

Left: Nicolas Poussin, The Holy Family on the Steps, 1648, oil on canvas, 73.3 x 105.8 cm (Cleveland Museum of Art; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0); right: Raphael, Madonna del Pesce (Madonna of the Fish), 1513–14, oil on canvas transferred to panel, 215 x 158 cm (Museo del Prado, Madrid)

For the figural group, Poussin cites Raphael, the 16th-century painter held in high regard in the 17th century. He repeats without exactly copying the Madonna’s sedes sapientiae twisted pose presenting the Christ Child to two figures in profile from Raphael’s Madonna del Pesce originally made for the church of San Domenico Maggiore in Naples. Her firmly planted right foot quotes Raphael’s Madonna del Prato.

Left: Joseph (detail), Nicolas Poussin, The Holy Family on the Steps, 1648, oil on canvas, 73.3 x 105.8 cm (Cleveland Museum of Art; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0); right: Andrea del Sarto, Madonna del Sacco, 1525, fresco, 191 x 403 cm (Basilica of Santissima Annunziata, Florence)

The figure of Joseph, recumbent in shadow on the steps, derives from Andrea del Sarto’s Madonna del Sacco from 1525, which in turn quotes Michelangelo’s Sistine Ceiling frescoes from 1512. The elder artist had painted the ancestors of Christ on the lunettes over the chapel’s windows. In the biblical figure of Naason’s relaxed recumbent pose behind the Virgin and Child, Poussin found his Joseph.

Nicolas Poussin, The Holy Family on the Steps, 1648, oil on canvas, 73.3 x 105.8 cm (Cleveland Museum of Art; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Intellectual discourse

Teeming with references both religious and art historical, The Holy Family on the Steps is a dense painting. The references, ranging from the commonplace to esoteric, offer viewers many entry points into the discussion. The painting’s greatest delights, however, reside in plumbing its depths.

Poussin, ever an ardent student of literature, antiquity, and art history, supplied artworks for people who enjoyed using details in the painting as springboards, connecting their knowledge to what they could see in the painting. Staid and careful where artists like Caravaggio were spontaneous, Poussin nevertheless provided liveliness, but in the discourse the painting prompted rather than on the canvas.