Identify the classical orders—the architectural styles developed by the Greeks and Romans used to this day.

Greek architectural orders. Speakers: Dr. Steven Zucker and Dr. Beth Harris

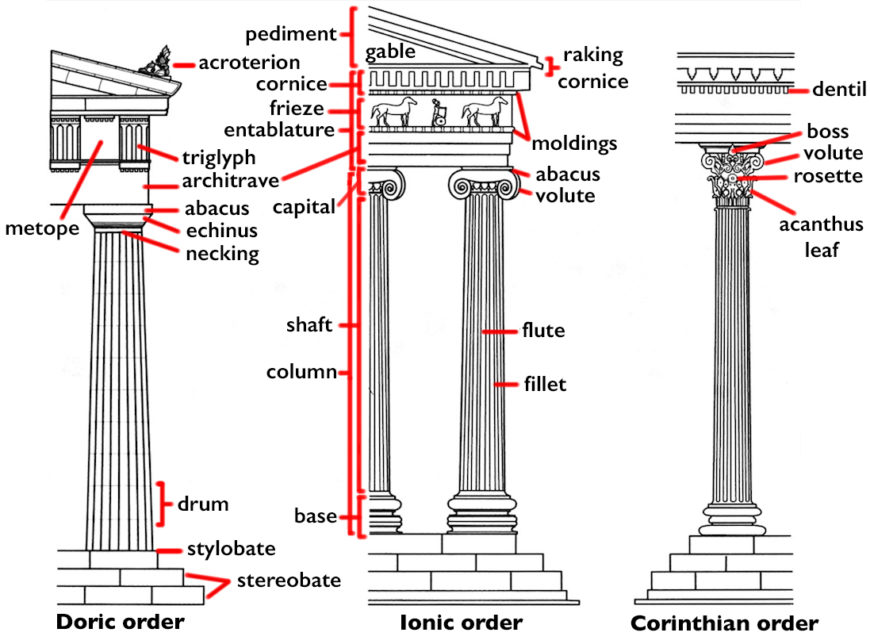

An architectural order describes a style of building. In classical architecture, each order is readily identifiable by means of its proportions and profiles, as well as by various aesthetic details. The style of column employed serves as a useful index of the style itself, so identifying the order of the column will then, in turn, situate the order employed in the structure as a whole. The classical orders—described by the labels Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian—do not merely serve as descriptors for the remains of ancient buildings, but as an index to the architectural and aesthetic development of Greek architecture itself.

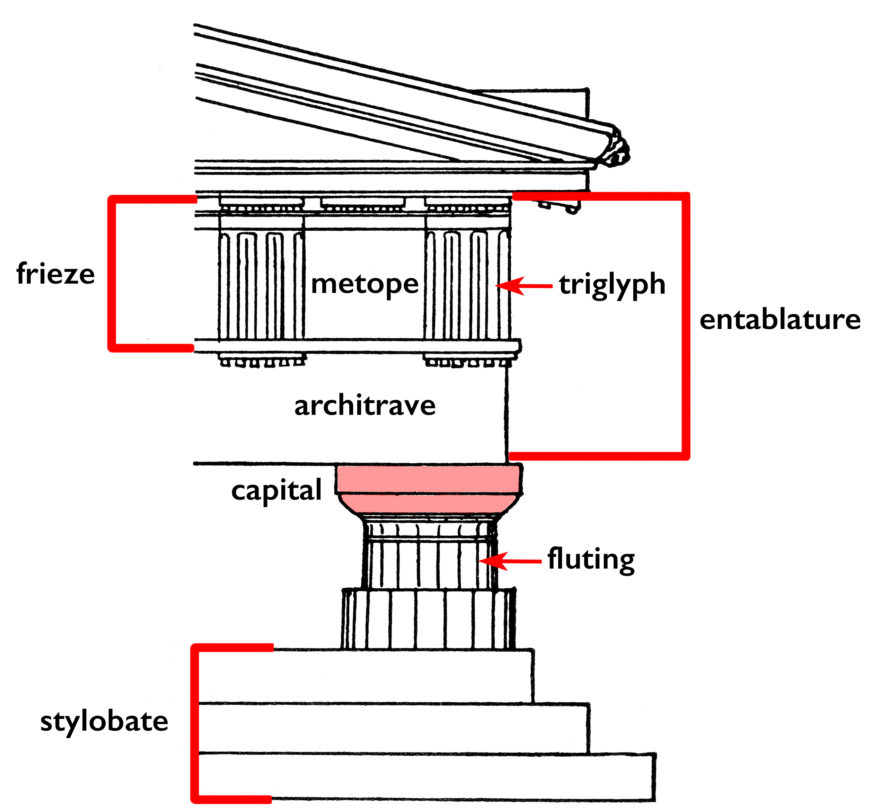

Doric order (underlying image from Alfred D. Hamlin, College Histories of Art History of Architecture, 1915)

The Doric order

The Doric order is the earliest of the three Classical orders of architecture and represents an important moment in Mediterranean architecture when monumental construction made the transition from impermanent materials (i.e. wood) to permanent materials, namely stone. The Doric order is characterized by a plain, unadorned column capital and a column that rests directly on the stylobate of the temple without a base. The Doric entablature includes a frieze composed of triglyphs and metopes. The columns are fluted and are of sturdy, if not stocky, proportions.

Iktinos and Kallikrates, The Parthenon, 447–432 B.C.E., Athens (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The Doric order emerged on the Greek mainland during the course of the late seventh century B.C.E. and remained the predominant order for Greek temple construction through the early fifth century B.C.E., although notable buildings of the Classical period—especially the canonical Parthenon in Athens—still employ it. By 575 B.C.E the order may be properly identified, with some of the earliest surviving elements being the metope plaques from the Temple of Apollo at Thermon. Other early, but fragmentary, examples include the sanctuary of Hera at Argos, votive capitals from the island of Aegina, as well as early Doric capitals that were a part of the Temple of Athena Pronaia at Delphi in central Greece. The Doric order finds perhaps its fullest expression in the Parthenon (c. 447–432 B.C.E.) at Athens designed by Iktinos and Kallikrates.

Ionic Capital, North Porch of the Erechtheion (Erechtheum), Acropolis, Athens, marble, 421–407 B.C.E. (British Museum; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Ionic order (photo: Coyau, CC BY-SA 3.0)

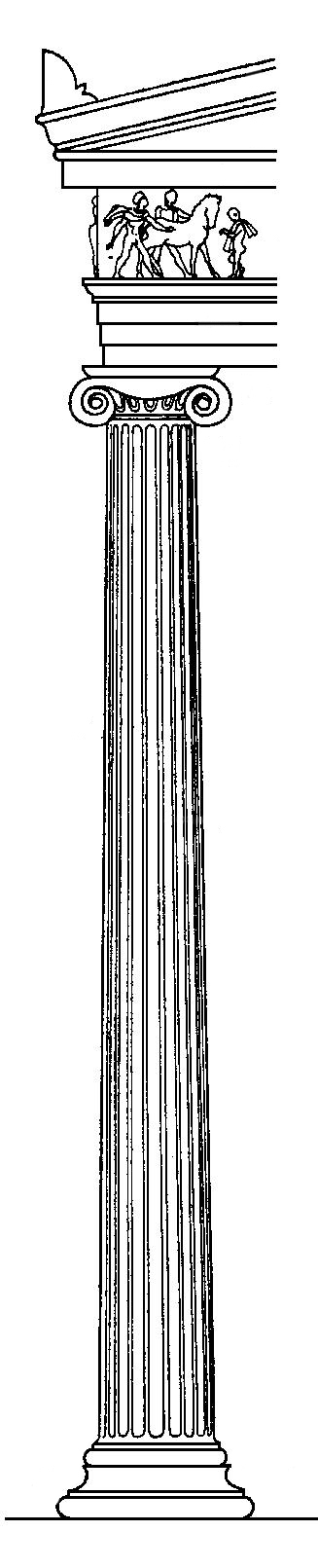

The Ionic order

As its name suggests, the Ionic Order originated in Ionia, a coastal region of central Anatolia (today Turkey) where a number of ancient Greek settlements were located. Volutes (scroll-like ornaments) characterize the Ionic capital and a base supports the column, unlike the Doric order. The Ionic order developed in Ionia during the mid-sixth century B.C.E. and had been transmitted to mainland Greece by the fifth century B.C.E. Among the earliest examples of the Ionic capital is the inscribed votive column from Naxos, dating to the end of the seventh century B.C.E.

The monumental temple dedicated to Hera on the island of Samos, built by the architect Rhoikos c. 570–560 B.C.E., was the first of the great Ionic buildings, although it was destroyed by earthquake in short order. The sixth century B.C.E. Temple of Artemis at Ephesus, a wonder of the ancient world, was also an Ionic design. In Athens, the Ionic order influences some elements of the Parthenon (447–432 B.C.E.), notably the Ionic frieze that encircles the cella of the temple. Ionic columns are also employed in the interior of the monumental gateway to the Acropolis known as the Propylaia (c. 437–432 B.C.E.). The Ionic was promoted to an exterior order in the construction of the Erechtheion (c. 421–405 B.C.E.) on the Athenian Acropolis.

East porch of the Erechtheion, 421–407 B.C.E., marble, Acropolis, Athens (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The Ionic order is notable for its graceful proportions, giving a more slender and elegant profile than the Doric order. The ancient Roman architect Vitruvius compared the Doric module to a sturdy, male body, while the Ionic was possessed of more graceful, feminine proportions. The Ionic order incorporates a running frieze of continuous sculptural relief, as opposed to the Doric frieze composed of triglyphs and metopes.

The Corinthian order

The Corinthian order is both the latest and the most elaborate of the Classical orders of architecture. The order was employed in both Greek and Roman architecture, with minor variations, and gave rise, in turn, to the Composite order. As the name suggests, the origins of the order were connected in antiquity with the Greek city-state of Corinth where, according to the architectural writer Vitruvius, the sculptor Callimachus drew a set of acanthus leaves surrounding a votive basket (Vitr. 4.1.9–10). In archaeological terms, the earliest known Corinthian capital comes from the Temple of Apollo Epicurius at Bassae and dates to c. 427 B.C.E.

Corinthian column capital 4th–3rd century B.C.E. (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

The defining element of the Corinthian order is its elaborate, carved capital, which incorporates even more vegetal elements than the Ionic order does. The stylized, carved leaves of an acanthus plant grow around the capital, generally terminating just below the abacus. The Romans favored the Corinthian order, perhaps due to its slender properties. The order is employed in numerous notable Roman architectural monuments, including the Temple of Mars Ultor and the Pantheon in Rome, and the Maison Carrée in Nîmes.

Acanthus leaf (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Legacy of the Greek architectural canon

The canonical Greek architectural orders have exerted influence on architects and their imaginations for thousands of years. While Greek architecture played a key role in inspiring the Romans, its legacy also stretches far beyond antiquity. When James “Athenian” Stuart and Nicholas Revett visited Greece during the period from 1748 to 1755 and subsequently published The Antiquities of Athens and Other Monuments of Greece (1762) in London, the Neoclassical revolution was underway. Captivated by Stuart and Revett’s measured drawings and engravings, Europe suddenly demanded Greek forms. Architects the likes of Robert Adam drove the Neoclassical movement, creating buildings like Kedleston Hall, an English country house in Kedleston, Derbyshire. Neoclassicism even jumped the Atlantic Ocean to North America, spreading the rich heritage of Classical architecture even further—and making the Greek architectural orders not only extremely influential, but eternal.

Additional resources

Learn more about ancient Greek architecture in three chapters in Reframing Art History: “Pottery, the body, and the gods in ancient Greece, c. 800–490 B.C.E., ” “War, democracy, and art in ancient Greece, c. 490–350 B.C.E.,” and “Empire and Art in the Hellenistic world (c. 350–31 B.C.E.).”

B. A. Barletta, The Origins of the Greek Architectural Orders (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001).

H. Berve, G. Gruben and M. Hirmer, Greek temples, theatres, and shrines (New York: H. N. Abrams, 1963).

F. A. Cooper, The Temple of Apollo Bassitas 4 vol. (Princeton N.J.: American School of Classical Studies at Athens, 1992–1996).

J. J. Coulton, Ancient Greek Architects at Work: Problems of Structure and Design (Ithaca NY: Cornell University Press, 1982).

W. B. Dinsmoor, The Architecture of Greece: an Account of its Historic Development 3rd ed. (London: Batsford, 1950).

W. B. Dinsmoor, The Propylaia to the Athenian Akropolis, 1: The predecessors (Princeton NJ: American School of Classical Studies at Athens, 1980).

P. Gros, Vitruve et la tradition des traités d’architecture: fabrica et ratiocinatio: recueil d’études (Rome: École française de Rome, 2006).

G. Gruben, “Naxos und Delos. Studien zur archaischen Architektur der Kykladen.” Jahrbuch des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts 112 (1997): pp. 261–416.

Marie-Christine Hellmann, L’architecture Grecque 3 vol. (Paris: Picard, 2002–2010).

A. Hoffmann, E.-L. Schwander, W. Hoepfner, and G. Brands (eds), Bautechnik der Antike: internationales Kolloquium in Berlin vom 15.–17. Februar 1990 (Diskussionen zur archäologischen Bauforschung; 5), (Mainz am Rhein: P. von Zabern, 1991).

M. Korres, From Pentelicon to the Parthenon: The Ancient Quarries and the Story of a Half-Worked Column Capital of the First Marble Parthenon (Athens: Melissa Publishing House, 1995).

M. Korres, Stones of the Parthenon (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2000).

A. W. Lawrence, Greek Architecture 5th ed. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1996).

D. S. Robertson, Greek and Roman Architecture 2nd ed. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1969).

J. Rykwert, The Dancing Column: On Order in Architecture (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1996).

E.-L. Schwandner and G. Gruben, Säule und Gebälk: zu Struktur und Wandlungsprozess griechisch-römischer Architektur: Bauforschungskolloquium in Berlin vom 16. bis 18. Juni 1994 (Mainz am Rhein: Verlag Philipp von Zabern, 1996).

M. Wilson Jones, “Designing the Roman Corinthian Order,” Journal of Roman Archaeology, vol. 2, 1989, pp. 35–69.

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

[flickr_tags user_id=”82032880@N00″ tags=”ClassicalOrders,”]