Episodes from the life of Christ (many of which also include his mother, the Virgin Mary) were among the most common subjects depicted in Medieval and Renaissance art. But where do these stories come from? And what exactly do these images represent?

Most of these stories come from the Christian New Testament (the second part of the Christian Bible), and especially from the Gospels attributed to Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John, which record the life and teachings of Jesus. Some episodes are also associated with legends or non-biblical texts (texts that were not in the Bible, but were nevertheless read by Christians).

Some images of Christ’s life originated in the early centuries of the Church, including representations of Christ’s birth, which date to the fourth and fifth centuries. Many such images closely parallel the arts of the Eastern Roman “Byzantine” Empire (read about scenes from the lives of Christ and the Virgin in Byzantine art). Other images developed later, such as Christ emerging from his tomb at the Resurrection, which appears in the eleventh century.

Medieval and Renaissance images of Christ’s life appear in a wide range of artistic media, on different scales, and in various public and private devotional settings. While these images vary based on the period, region, and circumstances of their production, this essay introduces common elements in scenes from the life of Christ, which had an enduring influence on the history of western art.

Commonly depicted subjects in medieval and Renaissance art

Fra Angelico, The Annunciation, c. 1438-47, fresco, 230 x 321 cm (Convent of San Marco, Florence; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The Annunciation

The angel Gabriel visits the Virgin Mary to announce to her that she will be the mother of God. At this moment, Jesus Christ is miraculously conceived, and God becomes flesh and blood. The Annunciation is described in Luke 1:26–38 and pictured here in a fresco by Fra Angelico at the Convent of San Marco in Florence.

Master of the Geneva Latini, The Visitation, c. 1470, Rouen, ink, tempera, and gold on vellum, book of hours: 19.5 x 13.1 cm France (The Cleveland Museum of Art, CC0 1.0)

The Visitation

Mary and Elizabeth, who are cousins, meet, as shown in this fifteenth-century manuscript illumination. Mary (left) is pregnant with Jesus and Elizabeth (right) is pregnant with St. John the Baptist. Elizabeth (and her son in her womb) recognize the miracle of Christ in Mary’s womb. The Visitation is recorded in Luke 1:39-56. An angel sometimes stands near the Virgin, as in this miniature, although no angels are mentioned in the biblical account.

Duccio, The Nativity with the Prophets Isaiah and Ezekiel, 1308-11 (National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.)

The Nativity

Matthew 1:18–2:12 and Luke 2:1–20 describe the Nativity of Christ. Mary gives birth to Christ in a stable while the animals watch. In Duccio’s Nativity, Joseph peers into the stable from the left side of the composition, while some other artworks show him sleeping (his minimized role in the scene emphasizes Mary’s virginity). The star that guides the Magi from the east shines overhead. A host of angels appear above the scene and announce Christ’s birth to shepherds. Midwives wash the newborn Christ child in the bottom left. View annotated image.

Adoration of the Magi, 1470–1480, Upper Rhine, Germany, cartapesta (papier maché) with polychromy and gilding, 29 × 22.4 × 4.5 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Adoration of the Magi

Three Magi (by tradition, kings from the East), follow a miraculous star that leads them to Christ, who has just been born in a stable (Matthew 2:1-12). The Magi offer gifts of gold, frankincense, and myrrh (frankincense and myrrh are aromatic tree resins), and worship the infant Christ. View annotated image.

Read about European depictions of Balthazar—one of the Magi—as an African king.

Ambrogio Lorenzetti, Presentation at the Temple, 1342, tempera and gold on panel, 257 x 168 cm (Le Gallerie degli Uffizi, Florence; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The Presentation

Mary and Joseph present Christ in the temple at Jerusalem as described in Luke 2:22–38. They encounter Simeon—who was told by the Holy Spirit that he would not die until he had seen the messiah—shown in Lorenzetti’s painting holding Christ into his arms. The prophetess Anna stands near Simeon, identifying Jesus as the Messiah with a pointing finger. View annotated image.

Baptism of Christ, Psalter of Eleanor of Aquitaine, KW 76 F 13, fol. 019r, c. 1185, Fécamp, Normandy (National Library of the Netherlands)

The Baptism of Christ

The Baptism of Christ is recounted in Matthew 3:13–17, Mark 1:9–11, and Luke 3:21–22 and appears here in the twelfth-century Psalter of Eleanor of Aquitaine. John the Baptist stands on the left, baptizing Christ in the Jordan River. A ministering angel stands on Christ’s other side, preparing to dress him when he emerges from the water. The Holy Spirit descends on Christ from above in the form of a dove. View annotated image

Duccio, The Temptation of Christ on the Mountain, 1308-11, tempera on poplar panel, 43.2 x 46 cm (The Frick Collection)

The Temptation

Following Christ’s baptism, the Holy Spirit leads Christ into the wilderness to fast for forty days, during which time he is tempted by Satan (Matthew 4:1–11; Mark 1:12–13; Luke 4:1–12). Duccio’s painting depicts the third and final temptation: “The devil took him to a very high mountain and showed him all the kingdoms of the world…and he said to him, ‘All these I will give you, if you will fall down and worship me.’ Jesus said to him, ‘Away with you, Satan! for it is written, “Worship the Lord your God, and serve only him.”‘ Then the devil left him, and suddenly angels came and waited on him.” (Matthew 4:8-11). View annotated image.

The Healing of the Blind Man and the Raising of Lazarus, 1120-40, fresco, made in Castile-León, Spain, 165.1 x 340.4 cm (photo: Sharon Mollerus, CC BY 2.0)

The Raising of Lazarus

The Raising of Lazarus, described in John 11:38–44, was one of the many miracles of Christ recorded in the Gospels. Christ was friends with Mary, Martha, and Lazarus, who were siblings. Lazarus becomes ill and his sisters send to Christ for help. Lazarus dies and is in the grave for four days before Christ raises him from the dead by calling him out of his tomb, shown on the right side of this fresco. View annotated image.

Giotto, Entry into Jerusalem, 1305-06, fresco, Arena (Scrovegni) Chapel, Padua (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Entry into Jerusalem

Christ rides into Jerusalem on a donkey, where he is greeted by crowds of people (Matthew 21:1–11, Mark 11:1–10, Luke 19:29–40, and John 12:12–19). These crowds welcome him into Jerusalem by waving palm branches and laying down their cloaks for him. View annotated image.

Take a guided virtual tour of the Scrovegni (Arena) Chapel in Padova, Italy.

Ugolino da Siena, The Last Supper, c. 1325-30, tempera and gold on wood, 38.1 x 56.5 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

The Last Supper

Christ eats dinner with his apostles and encourages them to eat bread and drink wine in remembrance of him (Matthew 26:20–29; Mark 14:17–25; Luke 22:14–23; I Corinthians 11:23–26), as shown in this painting by Ugolino da Siena. He also tells the apostles that one of them will betray him. View annotated image.

The Agony in the Garden, c. 1460, Naples, Italy, tempera colors, gold, and ink on parchment, 17.1 x 12.1 cm (The J. Paul Getty Museum, CC0)

Agony in the Garden

After the Last Supper, Christ goes to pray in the Garden of Gethsemane with his apostles (Matthew 26:36–46; Mark 14:32–42; Luke 22:39–46). He asks them to wait and pray with him, but they fall asleep. Anticipating his crucifixion, Jesus prays: “Father, if you are willing, remove this cup from me; yet, not my will but yours be done” (Luke 22:42). Artists often visualized Christ’s “cup” as a Eucharistic chalice, as in this miniature at the Getty Museum. In Luke’s Gospel, Christ’s anguish causes him to sweat blood, and an angel comes from heaven to strengthen Christ, two details that are sometimes also included in this scene. View annotated image.

Giotto, Kiss of Judas, 1305-06, fresco, Arena (Scrovegni) Chapel, Padua (photo: Wikimedia Commons, CC0)

Kiss of Judas

Judas, who has been paid 30 pieces of silver to betray Christ’s whereabouts to the Roman authorities, leads soldiers to Jesus and identifies him with a kiss, as shown here in Giotto’s fresco. Christ is arrested and led away. The episode is recorded in Matthew 26:47–56, Mark 14:–52, Luke 22:47–54, and John 18:1–11. View annotated image

Take a guided virtual tour of the Scrovegni (Arena) Chapel in Padova, Italy.

Ludwig Schongauer, Christ before Pilate; The Resurrection, c. 1477, oil on fir, 38.4 x 21 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Christ before Pilate

Roman soldiers take Christ to Pilate, the Roman prefect (Matthew 27:11–26, Mark 15:1–15, Luke 23:1–25, John 18:28–19:16). Pilate tries Jesus, but does not find him guilty. Pilate tells the angry crowd that he will release one prisoner, but they do not choose Jesus. As in many artworks, Schongauer illustrates a moment from Matthew’s Gospel: “When Pilate saw that he could do nothing, but rather that a riot was beginning, he took some water and washed his hands before the crowd, saying, ‘I am innocent of this man’s blood’” (Matthew 27.24). Pilate orders Christ to be whipped and crucified. View annotated image.

Master of the Codex of Saint George, The Crucifixion, c. 1330-35, Italian, made in Avignon, France, tempera on wood, gold ground, 45.7 x 29.8 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

The Crucifixion

Christ is crucified at Golgotha as his mother Mary and John the Evangelist watch. Mary is sometimes accompanied by other women who were followers of Christ, as in this fourteenth-century painting at the Metropolitan. Jesus is offered vinegar (or sour wine) to drink from a sponge, and soon dies. He is stabbed in his side with a lance after his death. The Crucifixion is described in Matthew 27:32–56, Mark 15:21–41, Luke 23:26–49, and John 19:16–37. View annotated image.

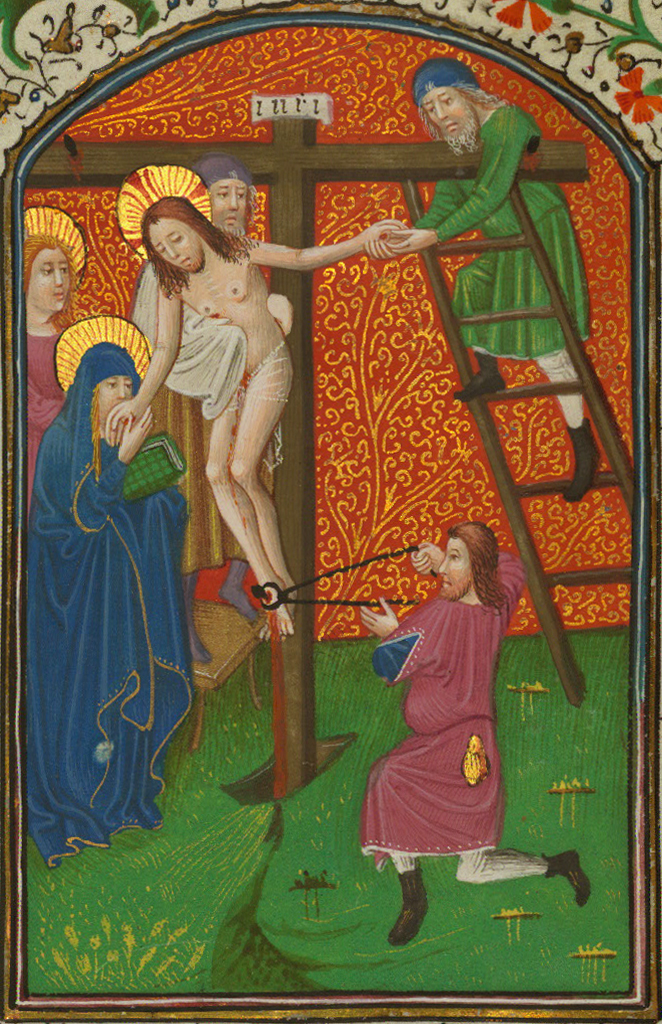

The Deposition, Book of Hours, Walters Manuscript W.246, fol. 25v, 1440-50, Bruges (The Walters Art Museum)

Descent from the Cross (also known as The Deposition)

Pilate gives Joseph of Arimathea permission to remove Christ from the cross and bury his body (Matthew 27:57-61, Mark 15:42-47, Luke 23:50-56, John 19:38-42). Joseph of Arimathea and Nicodemus, another follower of Christ, take Christ down from the cross. They bring a shroud for the body. Other figures often included in this scene are the Virgin Mary, St. John the Evangelist, and the three Marys (three women mentioned in the Gospels as followers of Christ, all named Mary but not including the Virgin Mary, Jesus’ mother).

The Women at the Tomb, mid 1200s, Belgium, possibly Bruges, tempera colors, gold leaf, and ink on parchment, leaf: 23.5 x 16.5 (The J. Paul Getty Museum, CC0)

The Marys at the Tomb

The Gospels describe women who followed Jesus as the first witnesses of Christ’s resurrection from the dead: Matthew 28:1–10, Mark 16:1–8, Luke 23:55–24:12, John 20:1–18. Tradition identified them as the three Marys: Mary Magdalene, Mary the mother of James, and Mary Salome; a later tradition identified them as the three daughters of St. Anne. The Marys go to the tomb to wash and anoint the body of Christ, but when they arrive, the large stone is rolled away from the door. An angel tells the Marys that Christ is not there. The Getty miniature includes the soldiers that Pilate posted to guard Christ’s tomb, described in Matthew’s Gospel: “An angel of the Lord came down from heaven and, going to the tomb, rolled back the stone and sat on it. His appearance was like lightning, and his clothes were white as snow. The guards were so afraid of him that they shook and became like dead men” (Matthew 28:2-4). View annotated image.

The Resurrection, Homilary, Walters Manuscript W.148, fol. 23v, first half of the 14th century, Lower Rhineland (The Walters Art Museum)

The Resurrection

Christ emerges triumphant from the tomb and carries the banner of the resurrection, often a white flag with a red cross. This scene is not explicitly described in the Gospels and appears as early as the eleventh century.

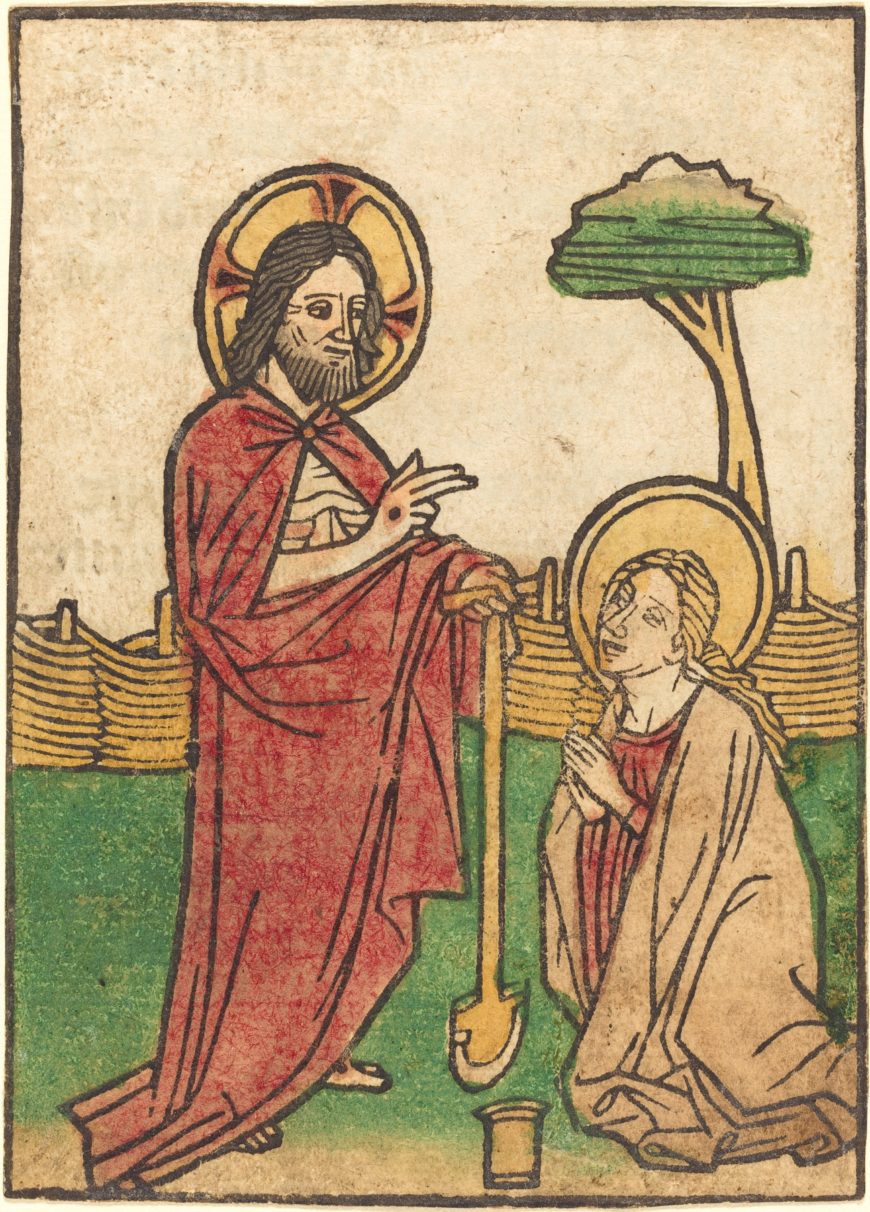

Ludwig of Ulm, Noli me tangere, c. 1450-70, German, hand-colored woodcut, 59.7 x 44.5 cm (National Gallery of Art)

Noli me Tangere

Mary Magdalene goes to the tomb to mourn Christ (John 20:11-18). She finds Christ, but initially mistakes him for the gardener. Sometimes, as in this woodcut by Ludwig of Ulm, Christ appears with gardening tools (in this case a spade). When Mary realizes that he is Christ, he says “Touch me not” or “noli me tangere” in Latin.

The Ascension, c. 1190-1200, English, tempera colors and gold leaf on parchment, 11.9 x 17 cm (The J. Paul Getty Museum, CC0)

The Ascension

After forty days with his disciples following his resurrection from the dead, Christ ascends into heaven (Luke 24:50–53, Acts 1:9–12). Sometimes, Christ is surrounded by a mandorla (an almond-shaped aureole of light). In other works, such as this English miniature, only Christ’s feet are visible as he ascends into the clouds above. The Virgin and Apostles stand below, gazing upward after Christ.

Pentecost, Ms. Ludwig VII 1, fol. 47v, c. 1030-1040, Ottonian, Regensburg, Germany, tempera colors, gold leaf, and ink on parchment, 23.2 x 16 cm (The J. Paul Getty Museum, CC0)

Pentecost

Pentecost depicts the descent of the Holy Spirit on the Apostles in the form of tongues of fire, as described in Acts 2. The Holy Spirit enables the Apostles to preach about the crucified and risen Christ in many languages so that people gathered in Jerusalem from many nations can understand. In this miniature, the Holy Spirit is also pictured as a dove, although this detail is not included in the biblical account.

Master of the Orléans Triptych, The Last Judgment, c. 1500, French, painted enamels on copper, partly gilded, center plaque: 25 x 22 cm , left plaque: 25 x 10 cm, right plaque: 25 x 10 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, CC0)

Last Judgment

References to the Last Judgment appear in the Gospels and elsewhere in the Christian New Testament, and Christ is often represented in art as judge at the end of time. These scenes often show Christ enthroned in heaven surrounded by saints and angels, who help him judge the souls of humankind, as shown in the center panel of this triptych. Angels call forth the dead from their tombs to be judged, pictured in the bottom of the center panel. The righteous enter the Kingdom of Heaven, a beautiful orderly place (left panel), and the damned go to hell where they are tormented by demons (right panel). View annotated image.

Additional resources

“The lives of Christ and the Virgin in Byzantine art”

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

[flickr_tags user_id=”82032880@N00″ tags=”StandardScenes,”]