Gentile Bellini, Procession in Piazza San Marco, c. 1496, tempera on canvas, 373 x 745 cm (Gallerie dell’Accademia, Venice; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Crammed with figures and teeming with details, the Procession in Piazza San Marco offers the viewer so much to take in that the story that the painting depicts is easy to overlook. The encompassing view, offering the beholder a perspective above the bustle of standing on the pavement, and precise details of costume and architecture, imply a documentary fidelity. But just as maps and other seemingly neutral visual materials make arguments, so too does this city view. No mere reproduction of a recurring city event, the Procession nestles a narrative event within a larger message of the miraculous character of the city of Venice—and the indispensability of the confraternity that commissioned the painting.

Made for the Scuola Grande di San Giovanni Evangelista confraternity, the Procession was one canvas in a series of nine that decorated the albergo, the board room, of the confraternity’s meeting house. It takes a markedly different approach than the large figures engaged in dramatic action characteristic of Italian Renaissance istoria paintings made in central Italy, such as Masaccio’s Tribute Money. The painting builds its argument through detail rather than through action.

Scene at the piazza (detail), Gentile Bellini, Procession in Piazza San Marco, c. 1496, tempera on canvas, 373 x 745 cm (Gallerie dell’Accademia, Venice; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

The scene unfolds in the wide space of the Piazza San Marco, the seat of Venice’s government and the location of the Basilica San Marco, the city-state’s most important church. Its onion domes, multicolored stone façade, and golden mosaics tower above the scores of tiny figures milling in the square. Dominican monks, the odd noblewoman, Venetian senators in red robes, citizens in black, and young men in the striped colorful stockings of the compagnie delle calze portray a range of Venetian residents (though Bellini has mostly excluded resident Jews, Black Africans, and foreign merchants, all of whom lived in Venice during the Renaissance). On the left, women in windows decorated with rugs watch from above. On the right, the procession exits the Porta della Carta, the door connecting the gap between the Basilica San Marco and the pink Ducal Palace.

The reliquary and baldachin (detail), Gentile Bellini, Procession in Piazza San Marco, c. 1496, tempera on canvas, 373 x 745 cm (Gallerie dell’Accademia, Venice; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

The procession continues across the foreground like a classical frieze. Members of the Scuola Grande di San Giovanni Evangelista wearing white confraternal robes carry heavy doppieri, the candlesticks that formed a large part of the brotherhood’s expenses. In the center of the painting, on the same axis as the basilica’s main portal, the brothers transport a golden reliquary under a baldachin adorned with flags bearing the shields of the city’s other large confraternities, the scuole grandi. Inside the reliquary was the Scuola Grande di San Giovanni Evangelista’s prize possession: a relic of a fragment of the True Cross.

The miracle story

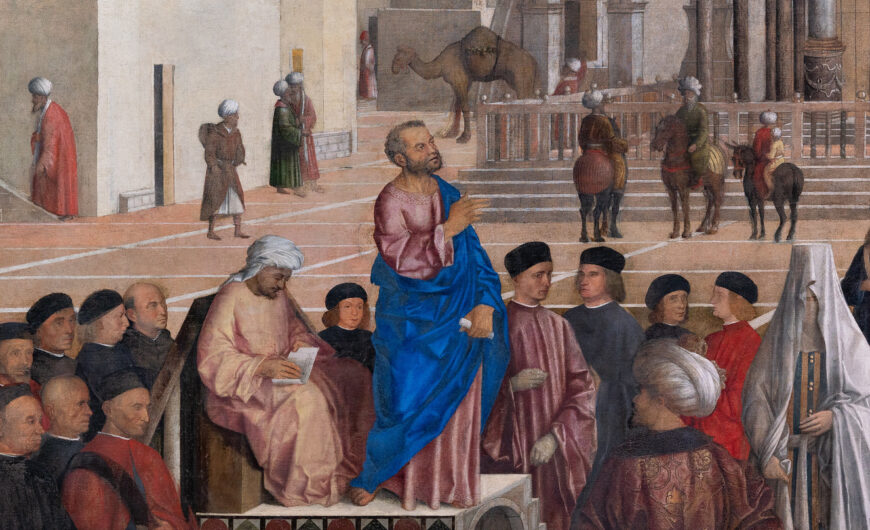

The Procession in Piazza San Marco reads as a cityscape or a scene of a recurring Venetian procession. Nevertheless, its 15th- and 16th-century viewers understood it as an istoria, a narrative painting. Nestled between confraternity brothers in a small gap in the procession to the right of the baldachin kneels a bare-headed man in red. His unobtrusive genuflection is the only indication in the tranquil scene that an event is occurring.

Jacopo de’ Salis kneels before the confraternity’s relic (detail), Gentile Bellini, Procession in Piazza San Marco, c. 1496, tempera on canvas, 373 x 745 cm (Gallerie dell’Accademia, Venice; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Confraternity members would have known—and been able to tell visitors to their meeting house—that the kneeling man was Jacopo de’ Salis, a merchant from Brescia, a town in Lombardy (in northern Italy). While on business in Venice, he received word that his son had become seriously injured in a fall. Before hurrying home to Brescia, the merchant paused to revere the confraternity’s relic of the True Cross. When he returned home, he learned his son had recovered miraculously the day of the procession. De’ Salis wrote the confraternity and promised to visit the relic again with his child, reinforcing the confraternity and city as facilitators of miracles. [1] Bellini’s composition renders this crucial miracle so unobtrusive, it’s almost invisible.

An art commission to rival all others

Devotional confraternities in Venice, like others found in medieval and early modern Europe, practiced general charity and provided mutual aid to members (e.g., financial assistance including dowries). In Venice, however, confraternities, known as scuole (singular scuola), performed in civic rituals. They were most visible during processions occurring on religious holidays significant to the state, tracing pathways through the city and inscribing confraternities into civic space.

Scuola Grande di San Giovanni Evangelista brothers singing from sheet music (detail), Gentile Bellini, Procession in Piazza San Marco, c. 1496, tempera on canvas, 373 x 745 cm (Gallerie dell’Accademia, Venice; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Paintings promote a vision of processions as orderly, but we know from archival records that struggles for primacy among confraternities could lead to arguments, even fistfights during these ceremonial state occasions. The Venetian state conferred the legal designation of “scuola grande,” meaning “large confraternity,” onto four brotherhoods at the time of Bellini’s painting, and among them, competition was intense. [2] Each confraternity sought prominence and primacy in Venice through ceremonial display, expressions of piety, and opulent art commissions. [3] A painting series by the city’s leading artists hyping the Scuola Grande di San Giovanni Evangelista’s relic displayed in the confraternity’s meeting house conferred immense prestige.

Scuola Grande di San Giovanni Evangelista meeting house, Venice (photo: Didier Descouens, CC BY-SA 4.0)

The True Cross fragment brought honor to the confraternity not only as a relic that had touched Christ, but also because of its provenance. In 1369, it had been donated by Philippe de Mézières, the Grand Chancellor of Cyprus, who had received it from the Patriarch of Constantinople. The relic’s origins in the eastern capital of Christianity reassured worshippers of its authenticity. [4] Documented miracles further guaranteed its genuineness.

The reliquary of the True Cross (detail), Gentile Bellini, Procession in Piazza San Marco, c. 1496, tempera on canvas, 373 x 745 cm (Gallerie dell’Accademia, Venice; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

In November of 1414, the same year the confraternity’s relic of the True Cross was said to have healed the daughter of member Ser Nicolò Benvegnudo, four members of the Scuola Grande di San Giovanni Evangelista decided to commission a series of narrative paintings relating miracles the relic had performed. [5] By the end of the 15th century, the Venetian diarist Marin Sanudo claimed the confraternity’s relic was the only one able to work miracles in all of Venice.

Quiet miracles in a holy city

The placidity of the Procession and the calmness of the miracle testify to Venice’s stability as a state and effortlessness as a facilitator of miracles. Indeed, the city-state was known as La Serenissima, “the most serene,” for its political steadiness. Depicting de’ Salis’s homage to the True Cross fragment instead of a more active moment in the story such as the boy’s fall or recovery centers the story on Venice and the act of devotion in the city to the confraternity’s relic. Therefore, active figures and dramatic movement typical of Florentine and Roman istoria would have been counterproductive to expressing Venetian values.

Basilica San Marco (detail), Gentile Bellini, Procession in Piazza San Marco, c. 1496, tempera on canvas, 373 x 745 cm (Gallerie dell’Accademia, Venice; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

The painting also allows the brothers to take pride in their confraternity and their city even though they belonged to social classes prohibited from holding government office. Venice restricted government office to a small group of noble families whose names were inscribed in the Libro d’Oro, “the golden book,” in the early 14th century. Citizens, wealthy or not, and professionals, clerical or laborers, were excluded from civic representation. Therefore, confraternities were one of the only ways in which non-noble Venetians could participate in ceremonial life and declare their presence in the city-state. Bellini’s painting shunts the head of state, the doge in an ermine cape and golden robes, to the side of the painting, where the minute figure is easy for the viewer to miss. The largest figures are the confraternity members, all non-noble as required by Venetian law that prohibited nobility from joining scuole.

The doge, a duke, shown as a small figure on the far right (detail), Gentile Bellini, Procession in Piazza San Marco, c. 1496, tempera on canvas, 373 x 745 cm (Gallerie dell’Accademia, Venice; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

True history

Bellini’s meticulous recreation of an actual place was not an outlier in the 15th-century Venetian tradition. Other paintings in the cycle reproduce Venetian urban topography with exactitude. The faithful details lend credibility to the depiction of both the city and miracles portrayed in the confraternity’s narrative paintings. [6] But Bellini baldly included a clearly untrue placement for the campanile.

If you stand on the Piazza San Marco today, the space will look mostly the same—except for the campanile, the bell tower, on the right. In real life, the campanile blocks a clear view of the Porta della Carta and Palazzo Ducale. Moving it discretely to the side across from the Palazzo Ducale in the painting let Bellini champion Venice’s marriage of church and state expressed by the ducal palace and basilica joined by the Porta della Carta.

Note how the campanile, the bell tower, has been moved in Bellini’s depiction of the piazza. Left: Gentile Bellini, Procession in Piazza San Marco, c. 1496, tempera on canvas, 373 x 745 cm (Gallerie dell’Accademia, Venice; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0); right: Piazza San Marco, Venice (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

The Procession in Piazza San Marco argues that Venice is a site of miracles so regular that they can occur without disrupting the flow of daily life and civic ritual that guarantee the city’s miraculous efficaciousness. The details reassure the viewer that they witness a true historical account and any changes only serve to portray a greater truth—Venice’s potent union of government and religion—than physical reality could provide.