The southern-Italian island of Sicily is often described as a stepping stone, a hub, or a crossroad of the Mediterranean Sea. To the North, the small island is separated from mainland Italy and its gateway to Christian Europe by only 2.5 miles. To the South, the Strait of Sicily, only 90 miles wide, joined Sicily to Ifrīqiyya (modern-day Tunisia) and to the Muslim territories of North Africa and the Maghreb. The waters of the Mediterranean Sea also connected the island to the more distant shores of the Fatimid Caliphate in Egypt, whose capital was Cairo, and to the Eastern Roman “Byzantine” Empire, whose capital was Constantinople (modern Istanbul). As a bridge across the Mediterranean, Sicily continuously attracted settlers and conquerors and encouraged trade, travel, commerce, as well as substantial artistic interaction throughout the region.

The Normans in Sicily

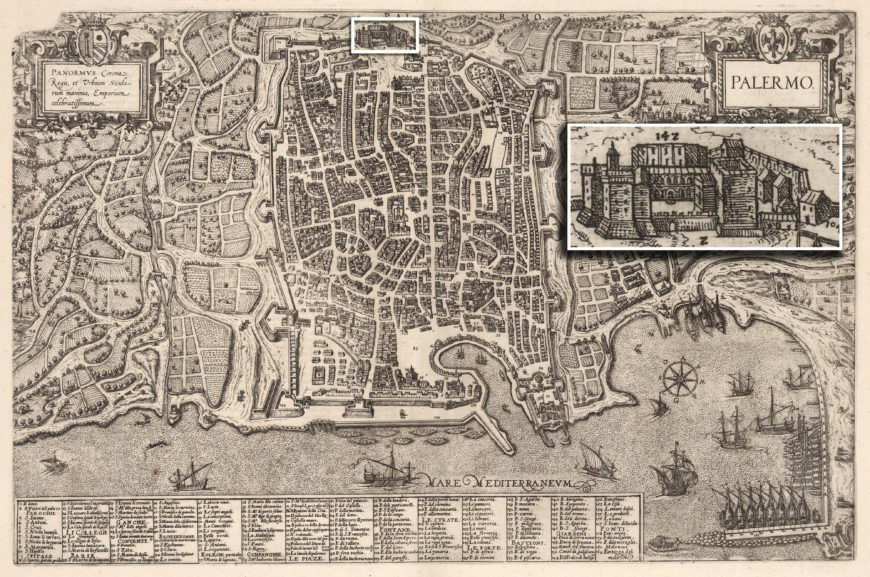

For centuries, Byzantine and then Islamic rulers governed the island of Sicily. In the eleventh century, warring southern Italian rulers, Byzantines, and Lombards alike hired Norman mercenaries from Northern France to aid them in their struggles against each other and against local Muslims. Setting out from Northern France, the Norman invaders gradually conquered the region for themselves, securing Southern Italy and Sicily by 1091. During this same period, Normans were also invading England, and as a result, the Normans were able to establish independent outposts in both Sicily and England, where they drew upon local artistic and architectural traditions in their monuments. In Southern Italy and Sicily, the Normans unified the entire region as the Kingdom of Norman Sicily—which endured from 1130 to 1194—with the city of Palermo as its capital.

Map of Palermo by Georg Braun and Franz Hogenberg with detail of the Palazzo Normanni (royal palace), 1588 (David Rumsey Historical Map Collection)

Under Norman kings Roger II, William I, and William II, Sicily flourished as a multiethnic center. Although the Norman kings were Latin Christians, loyal to the Pope in Rome, they governed a diverse, predominantly non-Latin-Christian population and fostered a multicultural ambience on the island. Their royal policies actively borrowed and reformulated local Greek (Byzantine) and Islamic cultural, religious, and administrative traditions and invoked those of rival political powers. As part of this policy, the Norman kings patronized art and architecture that brought together the distinctive visual cultures of the Mediterranean region—Byzantine, Islamic, and Romanesque. In so doing, they reinvented and presented themselves as legitimate Christian rulers to their subjects and peers.

Interior of the Cappella Palatina looking west, c. 1130–43, Palermo (photo: Ariel Fein, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Royal Architecture

The Cappella Palatina

Detail of muqarnas ceiling, Cappella Palatina, c. 1130–43, Palermo (photo: Ariel Fein, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

As part of their vast project to transform Palermo into the thriving capital of their new kingdom, the Norman kings built on an unprecedented scale. They furnished the kingdom with an elaborate royal palace, the Palazzo Reale (also known as the Palazzo Normanni), and its prized chapel, the Cappella Palatina, cathedrals in nearby Cefalù and Monreale (view locations on map), and extensive suburban dwellings. The most famous of the Norman royal monuments, the Cappella Palatina masterfully combines diverse architectural and decorative sources, including Byzantine-style mosaics, an Islamic-style painted muqarnas ceiling, opus sectile floors, and multicolored marble and stone wall revetments. The resulting aesthetic transformed the building into a visual manifesto of the king’s Mediterranean ambitions.

Cefalù Cathedral

Detail of central apse with Pantokrator, Cefalù Cathedral, 1131–1240 (photo: Gun Powder Ma, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Like the Cappella Palatina, the Norman kings’ other churches and cathedrals similarly evoked a synthesis of Byzantine, Islamic, and Romanesque forms. Roger II’s Cefalù Cathedral (view location on map), built between 1131 and 1240, intertwines the region’s diverse decorative traditions. Its overall design is reminiscent of Norman and French architecture in Northern Europe, following a Latin abbey design, and furnished its interior with mosaics executed in a Byzantine style, including images of Christ Pantokrator, the Virgin, apostles, and prophets in the apse. While the high quality of the chapel’s mosaics has led many scholars to conclude that Roger II imported Byzantine craftsmen to Sicily to decorate his churches, it is also possible that the chapel’s mosaics were executed by local artisans.

Central apse with Pantokrator, Virgin, apostles, and prophets, Cefalù Cathedral, 1131–1240 (photo: Ariel Fein, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

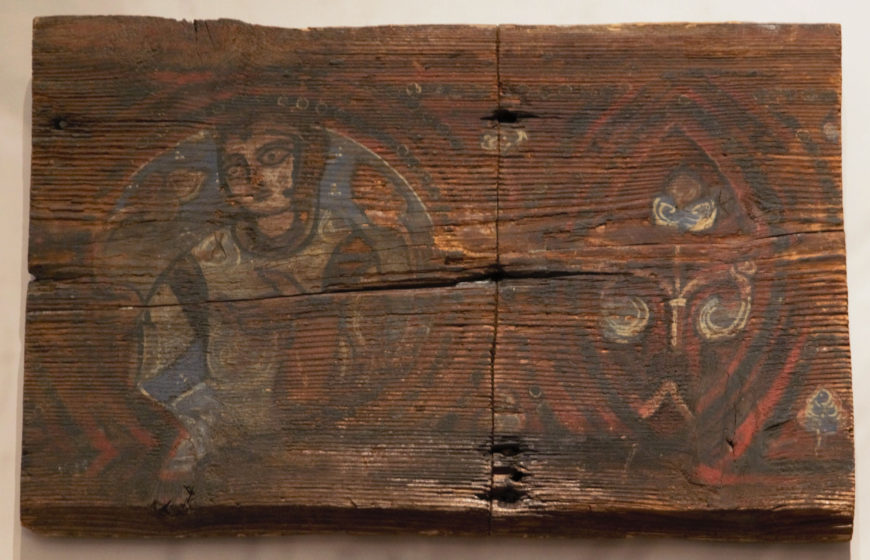

Moreover, Islamic-style painted wooden trusses and star-shaped panels surmount the nave. Their painted scenes, like those of the Cappella Palatina’s muqarnas ceiling, feature themes of courtly life drawn from an Islamic repertoire. The origins of the ceilings’ builders and painters remains a contentious issue, with scholars suggesting Sicily itself, Fatimid Egypt, North Africa, northern Syria, and northern Iraq.

Bichromatic inlaid decoration, Monreale Cathedral exterior, 1174 (photo: Ariel Fein, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Monreale

Similarly, King William II’s crowning architectural achievement can be seen at Monreale (view location on map): a large complex comprising a cathedral church, monastery, and cloister, which was completed in 1174. On the church’s eastern façade, Islamic-style decoration of repeating ogival arches and geometric medallions are formed by alternating black and white stone and marble.

On its interior, the Cathedral is composed almost entirely of flat surfaces, providing ample space for mosaic decoration. In the central sanctuary, images of the Pantokrator, Virgin, and saints adorn the central apse, while side apses feature scenes from the lives of Saints Peter and Paul. The transepts and aisles contain scenes from the life of Christ as well as scenes from the Old Testament and the life of the Virgin.

A pair of mosaic panels portray William II being crowned directly by God and donating his church to the Virgin. Positioned in the sanctuary, directly above the royal throne and the bishop’s ambo, or platform, they prominently represent the king’s presence within the church and the sacred space of the sanctuary. Moreover, as William appears in royal regalia reminiscent of a Byzantine emperor, the panels conveyed his desire to emulate the wealth and prestige of the Byzantine Empire.

Left: Christ crowning William II; right: William II presenting his church to the Virgin, Monreale Cathedral, 1174 (photos: Ariel Fein, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Royal dwellings

In addition to ecclesiastical buildings, the Norman kings also constructed suburban royal dwellings for recreation and hunting set in the midst of luxuriant gardens. In their architecture and cultivation of the surrounding verdant landscapes, these palaces drew heavily upon Islamic architecture and garden culture.

William I and II built their palaces, La Zisa and La Cuba in the midst of the park of Genoardo, which takes its name from the Arabic phrase Jannat al-ard, meaning “earthly paradise.” La Zisa (1164–75) towers over a landscape of fertile gardens, embellished by fountains and large ponds, formed by impressive feats of hydraulic engineering.

Its central Fountain Hall is decorated by an elaborate muqarnas hood and Arabic inscriptions describing the hall as “paradise on earth made manifest.” At the heart of the salon stands an impressive Islamic-style wall fountain with a sloped water chute (shādirwān), featuring furrows in a zig-zag pattern. The scalloped surface created rippling sounds and patterns in the water as it circulated through an elegant system of fountains culminating in a great fish-pond in front of the palace. A depiction of a similar fountain can be seen in the painted muqarnas ceiling of the Cappella Palatina.

The Royal Mint and Workshops

Gold tari of Roger II with Greek (left) and Arabic (right), 1142 (The Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Alongside monumental architecture, the Norman kings disseminated their message of legitimate rule through coinage, multilingual texts, and objects. Despite the changes in political rule, the Norman royal mint continued to produce and circulate the Sicilian tari, a gold quarter dinar first issued in Muslim Sicily (before being conquered by the Normans). After his coronation, King Roger II’s tari staged his authority using both Arabic and Greek (the language of the Byzantines). One side of the coin bears a cross with the Greek inscription ICXC NIKA (Jesus Christ will conquer) encircled by the Arabic name of the mint and date of minting. The reverse, written entirely in Arabic—a vernacular and intellectual language in Norman Sicily at this time—displays the name and honorific of the king as well as the name of the mint and date in the year of the hijra, or the Islamic lunar calendar. The coin thus presents an unambiguous statement of the strength of the Sicilian state and of Norman kingship in the dominant textual and symbolic languages of the medieval Mediterranean.

Hunting scenes on a painted ivory casket, 12th–13th century, Palermo, Cappella Palatina, Treasury (photo: Ariel Fein, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Coronation Mantle, 1133/34, fabric from Byzantium or Thebes, samite, silk, gold, pearls, filigree, sapphires, garnets, glass, and cloisonné enamel, 146 x 345 cm (Schatzkammer, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna) (photo: Brad Hostetler, CC BY 2.0)

The precious jeweled, ivory, and textile products of the royal workshops likewise combined a variety of visual forms, styles, and languages. Along with King Roger II’s coronation mantle, with its Islamic-style and Arabic epigraphy, painted ivory caskets similarly paired Christian and Islamic scenes. The casket shown here, composed of a rectangular wooden box with thin ivory plaques fixed with ivory pegs along its exterior, is decorated on all sides with images painted in black and gold leaf. Scenes of the hunt common in Islamic art, such as falconers pursuing gazelles with falcons and greyhounds and a hunting leopard catching its prey, adorn the sides of the casket, while a medallion of Christ flanked by two saints is rendered on the lid.

Documenting Religious Diversity

The majority of the surviving art and architecture from Norman Sicily was built by and for the island’s Latin-Christian Norman kings. However, some surviving works reveal glimpses of the art and identity of the island’s diverse population. The most famous of these monuments is the Santa Maria dell’Ammiraglio in Palermo, better known as the Martorana. George of Antioch, the Arab-Christian grand-vizier, or prime minister, to King Roger II, built the church as a private burial chapel for himself and his family as well as for the city’s Greek and Arab-Christian communities. On the one hand, it closely resembles King Roger II’s Cappella Palatina in its mosaics, opus sectile floors, and marble revetments. On the other hand, the church’s Arabic epigraphy draws more heavily upon George’s own Arab-Christian identity. The church’s mosaic dome, with images of Christ Pantokrator surrounded by archangels, is encircled by a narrow band of wood, now faded, but once brightly painted with the Arabic translation of two texts from the Greek liturgy.

Dome with Christ Pantokrator surrounded by archangels and Arabic and Greek epigraphy, Martorana Church, Palermo, 1143 (photo: Ariel Fein, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Tombstone with inscriptions in four languages (Latin, Greek, Arabic, and Judeo-Arabic), white marble with opus sectile decoration, 1149, Palermo, Museo della Zisa (photo: Ariel Fein, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Similarly, an opulent white marble funerary epitaph commemorates the death of Anna, mother of Grisandus, a priest working in the Cappella Palatina. Surrounding the vibrant, multicolored opus sectile cross are four inscribed texts—Latin (left), Greek (right), Arabic (bottom), and Judeo-Arabic (Arabic written in Hebrew script; top). While few people would have been able to read the quadrilingual epitaph in its entirety, even an illiterate viewer would have understood, or could have been told, that the four scripts represented the four religious communities of the Kingdom. Moreover, its opus sectile ornament would have further reminded the viewer of the decoration of the island’s royal churches and palaces, thus visualizing the prestige of its patron and the deceased.

These buildings and works of art are expressions of a unique Norman Sicilian cultural and visual identity. Drawing upon local styles on the island, as well as more distant traditions from Byzantium, Fatimid Egypt, the Maghrib, and the Levant, the kings and courtiers of Norman Sicily fashioned and mobilized Norman Sicilian visual culture in promoting their royal ideology and articulating their religious identities.

Additional Resources

The Norman Sicily Project: Documenting Sicily’s First Kingdom, 1061-1194

The Medieval Kingdom of Sicily, A Visual Resource of Historical Sties c. 1100-c.1450

Lisa Reilly, The Invention of Norman Visual Culture: Art, Politics, and Dynastic Ambition (Cambridge University Press, 2020)

William Tronzo, The Cultures of his Kingdom: Roger II and the Cappella Palatina in Palermo (Princeton University Press, 1997)