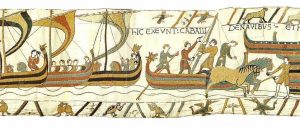

Horses disembarking from Norman longships, Bayeux Tapestry, c. 1070, embroidered wool on linen, 20 inches high (Bayeux Museum)

The invasion

On September 28, 1066, the tiny community of Pevensey (on the south-east coast of England), huddled inside the ruins of a late Roman fortification. They would soon be overwhelmed with the arrival of William, Duke of Normandy, and an army intent on invasion. Thousands of invaders had crossed the English Channel from Normandy on hundreds of open longships that were big enough to carry cavalry horses and the supplies needed to lay siege to the coastal cities guarding England.

Map showing the coasts of Normandy (in present-day France) and the location of the Battle of Hastings, in England

William had been preparing for the invasion since the last Anglo-Saxon king of England, Edward the Confessor, had died without a direct heir months earlier.

Edward had been succeeded by a newly appointed ruler, Harold Godwinson, but both William and the King of Norway, Harold Hardrada, also laid claim to the throne. Harold Hardrada had crossed the North Sea to invade near present-day Newcastle in the north of England, arriving at almost exactly the same time as William’s army made land further south. Forced to defend two coasts almost three hundred miles apart in quick succession, Harold Godwinson succeeded in defeating the king of Norway, but fell on the field at the Battle of Hastings, just up the coast from Pevensey, shot through the eye with an arrow. Harold’s sizeable army was no match for the mounted warriors William had brought from Normandy. His forces quickly marched west, to Dover and Canterbury, then east, leaving devastation in their wake. By Christmas, 1066, William the Conqueror had been crowned king of England, but facing a rebellion, he continued to lay waste to a huge swath of the country before he had all of England firmly within his grasp.

The death of King Harold at the Battle of Hastings (detail), Bayeux Tapestry, c. 1070, embroidered wool on linen, 20 inches high (Bayeux Museum)

Weaving a Norman tale

The works of art and architecture made in the wake of this invasion testify to the power of art as a tool for colonization. Perhaps the most famous of these is the Bayeux Tapestry. Within twenty years of the Norman Conquest of England, needle-workers embroidered dozens of scenes describing the invasion onto this 230-foot-long linen strip using wool and linen yarn. Between narrow upper and lower borders populated by animals, people and objects that act as a subtle commentary on the central narrative, a history of the Norman Conquest unscrolls from left to right, ending abruptly with a tattered, incomplete scene of mace-wielding Anglo-Saxon foot soldiers fleeing the victorious Normans. Embroidered Latin titles help to identify people, places and events.

Wounded soldiers and horses (detail), Bayeux Tapestry, c. 1070, embroidered wool on linen, 20 inches high (Bayeux Museum)

Scholars have never pinned down where or by whom the embroidery was carried out, or where it was meant to be displayed—a mystery compounded by the fact that this is the only storytelling textile strip of this sort preserved from the Middle Ages. In it, William is portrayed ordering his men to build a fleet of longships, stock them with arms and armor, food, wine, and horses, and set sail for England, where they feast, plan, and finally attack. The ensuing slaughter is unflinchingly rendered: in the lower border, dismembered bodies are stripped by battlefield looters. The style of the tapestry, with its gangly-limbed, beaky-nosed figures, agitated gestures, stolid drapery folds, abrupt changes in scale, and multicolored trees made of rubbery, interlaced fronds, has similarities to other works found on both sides of the Channel. Anglo-Saxon England and the Duchy of Normandy had been exchanging artwork, artists, clergy, and nobles well before the Conquest (their rulers were closely related—King Edward the Confessor’s mother, Emma of Normandy, was William the Conqueror’s great aunt).

Normans first meal in England, at the center is Bishop Odo, who gazes out as he offers a blessing over the cup in his hand (detail), Bayeux Tapestry, c. 1070, embroidered wool on linen, 20 inches high (Bayeux Museum)

If we can’t use style to judge where the tapestry was made, we can instead turn to the story, which displays an indisputably Norman bias, to identify its intended audience. Many medieval texts retold the events of the invasion from both the Anglo-Saxon and Norman perspectives, but Bishop Odo of Bayeux, William’s half brother, figures prominently in the Bayeux tapestry, where he is shown blessing a feast on the eve of battle, advising William, and rallying the troops. It is likely, then, that Odo commissioned the tapestry to celebrate his brother’s victory, and the tale that unfolds along its length highlights William’s (and Odo’s) valor and the supposed wrongdoings of Harold Godwinson, who is depicted swearing an oath to be William’s vassal, but then allowing himself to be crowned King of England. The tapestry completely ignores Harold’s victory over the Norwegian king, instead focusing on events of interest to Normans.

Preparations for war, including the building of a motte-and-bailey (detail), Bayeux Tapestry, c. 1070, embroidered wool on linen, 20 inches high (Bayeux Museum)

Motte-and-bailey castles

While the tapestry’s renditions of ships, weapons, horses, feasts and buildings have been mined by historians for information about daily life and military campaigns, many details are doubtless the result of artistic license. Still, the tapestry showcases some important Norman innovations. After the feast presided over by Bishop Odo, the invaders are shown shoveling dirt onto a striped mound crowned by a structure labeled “Hesteng ceastra“ (above). This is the castle of Hastings, one of several such castles (including one at Dover, discussed below, as well as the Tower of London) that William had built during and after his invasion. With these, he imported into England a type of defensive structure that was typical in Normandy and became essential for establishing control over his new English subjects.

The simplest of Norman castles comprised a mound, or motte, of alternating layers of earth and stones, topped with a wooden palisade and an enclosed residence, or keep, and surrounded by a ditch. Either surrounding this or contiguous with it was an open yard, or bailey, ringed with a wooden defensive barrier. Such defenses could be thrown up quickly and made use of existing land features. They provided security for the soldiers, horses, and equipment necessary to subdue the surrounding inhabitants, a vantage point from which to observe potential foes, and a looming presence to intimidate them.

Model of a motte-and-bailey (Carisbrooke Castle, 14th century, England) (photo: Charles D. P. Miller)

Lacking a standing professional army that could defend the walls of a city, medieval rulers like William appointed nobles to subdue parcels of the countryside in return for land and goods. If a castle’s location proved to be advantageous in the long term, the wooden structure on top was replaced with a masonry keep that provided permanent and more comfortable housing for the governing lord and his family. Round, rectangular, or faceted, these could be hollow shell keeps with buildings clustered against an exterior wall, or solid great towers, like the keep at Dover (below).

Aeriel view of Dover Castle, 12th century (Kent, England) (photo: Lieven Smits)

Topping these structures one often sees crenellations, which allowed archers to defend the perimeter while sheltering behind a stone wall. At Dover, as was typical, the wooden palisade surrounding the bailey was over time replaced by multiple concentric stone walls, a moat, and a barbican (an outer fortified gate).

With its towering presence, the motte-and-bailey castle combined the practical functions necessary to govern a rural population or the inhabitants of a conquered city with the symbolism of domination.

Durham Cathedral on the River Wear, Norman construction founded 1093 (Durham, England) (photo: Domstu)

A Norman cathedral

William the Conqueror had first visited Durham Cathedral—then an Anglo-Saxon stone church—on its peninsula in a bend of the River Wear (above) on his first northern campaign. Durham Cathedral was an important touchstone of Anglo-Saxon national identity, holding the relics of Cuthbert, their patron saint. Recognizing its strategic importance, William fortified one end of the site with a motte-and-bailey castle, and invited another Norman, William of Saint-Calais (who then became Bishop William), to take over the venerable cathedral and remake it in the image of a Norman church. Bishop William expelled the clergy he found there and replaced them with Benedictine monks. By 1093, he had begun construction on the largest and most technically innovative Norman church of its time.

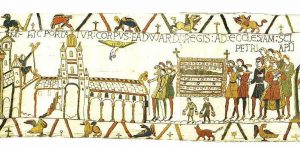

Edward the Confessor’s body being carried into Westminster Abbey, Bayeux Tapestry, c. 1070, embroidered wool on linen, 20 inches high (Bayeux Museum)

The Anglo-Saxons were already familiar with some Norman building practices and styles. In the Bayeux Tapestry, we see Edward the Confessor’s body carried to Westminster Abbey, which had been dedicated just days before his death. The church is depicted as a substantial structure with arcades (here, rows of columns topped with arches), clerestory windows, a transept and multiple towers. Edward had built it to be his own burial church, and excavations show that it probably resembled a Norman abbey near where Edward had spent much of his youth. At the time, observers described Westminster Abbey’s style as new and unusual. In the wake of the Conquest, however, major English churches were built or rebuilt only in this style rather than in the then prevalent Anglo-Saxon style, marking Norman control of the Church in starkly visual terms.

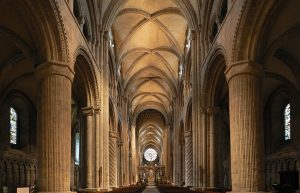

William the Conqueror and his wife, Matilda, had already commissioned impressive church buildings in their Norman capital city, Caen, that showcased the key characteristics of the Norman style. We can also see these at Durham, begun after William’s death but still part of the legacy of his invasion. A façade with two monumental towers looms over the fortifications and the steep banks of the Wear surrounding Durham’s peninsula. Behind this façade, a broad nave is separated from aisles by massive arches framed with complex decorative stone moldings, sitting on gigantic alternating piers.

Interior of Durham Cathedral, Norman construction founded 1093 (Durham, England) (photo: Oliver-Bonjoch)

Heavy stone, cleverly disguised

The clerestory windows of the nave and transept sit behind an interior passage and yet another arcade that create the effect of a multi-layered wall. Soaring over this multitude of arches are gargantuan ribbed groin vaults that covered the broad main area of the church, were probably the earliest and certainly the widest in Norman architecture. Their lightness and clever variations in curvature and height attest to the technical prowess of the builders. Stonemasons embellished the arches and piers with intricately carved patterns, and incised the outer wall of the aisle with interwoven arches. With these layers and details, the cathedral’s builders and masons emphasized the colossal weight of stone that supports the vaults, while at the same time diffusing this effect of weightiness using surface ornamentation. Together the technically demanding vaults and the wealth of hand-carved decoration broadcast the power of the cathedral and its bishop, who had the means to command the materials and artisans necessary to build such a monument.

Interior of Durham Cathedral, Norman construction founded 1093 (Durham, England) (photo: Simon Varwell)

Led by a decisive ruler, the Norman invaders at the beginning of the eleventh century brought with them a rich set of artistic and architectural approaches that helped them display their new power and authority over the Anglo-Saxon population.