Durham Cathedral (Durham, England), begun c. 1093. Speakers: Dr. Steven Zucker and Dr. Beth Harris

A building boom

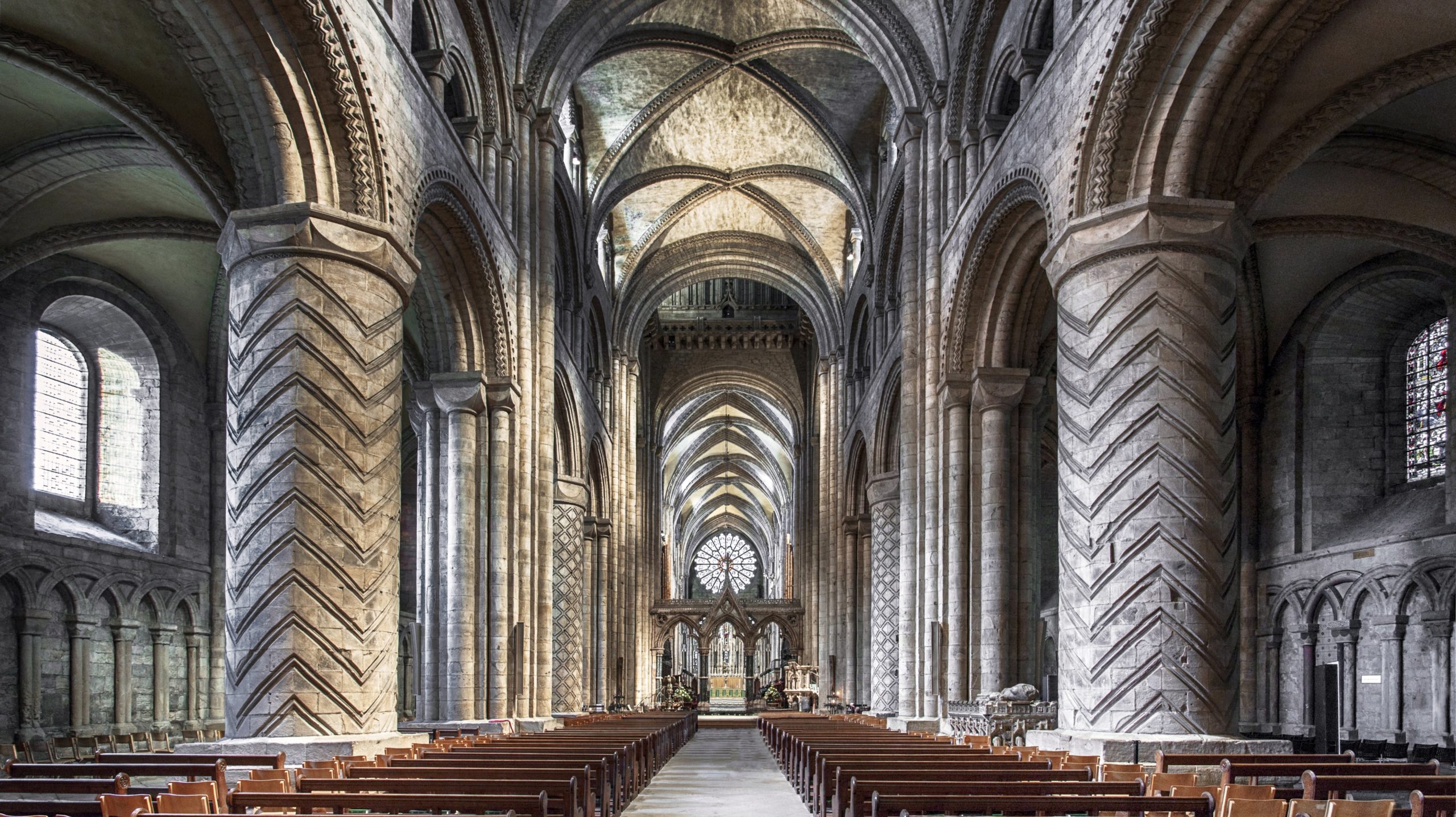

Despite being perched, somewhat snugly, between a cliff above the River Wear to its west and an abrupt incline to the east, the cathedral complex at Durham (begun 1093) was built almost to the largest proportions its tiny peninsula would allow. With walls regularly exceeding three meters in thickness and a final length of more than four hundred feet, it was once counted among the largest and most ambitious structures, not only of its generation, but almost of any following the decline of Roman imperial power in western Europe.

Between the late fifth and early twelfth centuries in fact, only three churches in western Europe could rival the size of Old St Peter’s in Rome. That enormous church was begun by the Roman Emperor Constantine in 318 C.E., soon after the Roman Empire (which included England) became officially Christian. In England, however, ground was broken on nine such giants—including Durham—in less than a generation. What sparked this building boom in the late eleventh century?

In September 1066, thousands of invaders led by William, the Duke of Normandy (also known as William the Conqueror) crossed the English Channel from Normandy (Northern France). The last pre-Norman King of England (Edward the Confessor) had died without a direct heir. By Christmas, 1066, William had been crowned King of England.

Durham Cathedral is one measure of the swift and profound transformation brought about by the Norman Conquest in England in the eleventh and twelfth centuries: not only a new art and architectural style—what is variously referred to as Anglo-Norman or English Romanesque—but an unprecedented and almost military-industrial mode of construction. Another was the sudden influx of architectural elements such as rounded arches, supremely thick walls, alternating piers and columns, barrel vaults, and decorative arcading, among other motifs, that defined Norman and early Christian architecture on the Continent. “England was being filled everywhere with churches,” wrote one bishop named Herman from Ramsbury, “. . . they were magnificent, marvellous, extremely long and spacious, full of light and also quite beautiful.” [1]

Durham Cathedral (photo: alljengi, CC BY-SA 2.0)

No written sources from the period are known to argue that a cathedral should be made large or, for that matter, why. And yet it is obvious from their sheer concentration that architectural gigantism must have been thought to carry a very powerful socio-political endowment. Dozens of fortified strongholds, castles, and halls followed within eighteen months of the invasion, and many hundreds of smaller parishes, priories, chamber blocks, water mills, and houses rose in tandem. It was, in all likelihood, nothing less than the most prodigious building program in Europe, by volume, per capita, prior to the Industrial Revolution.

Galilee chapel (begun 1175), Durham Cathedral (photo: Nick Thompson, CC BY-NC 2.0)

A new kind of sculptural decoration

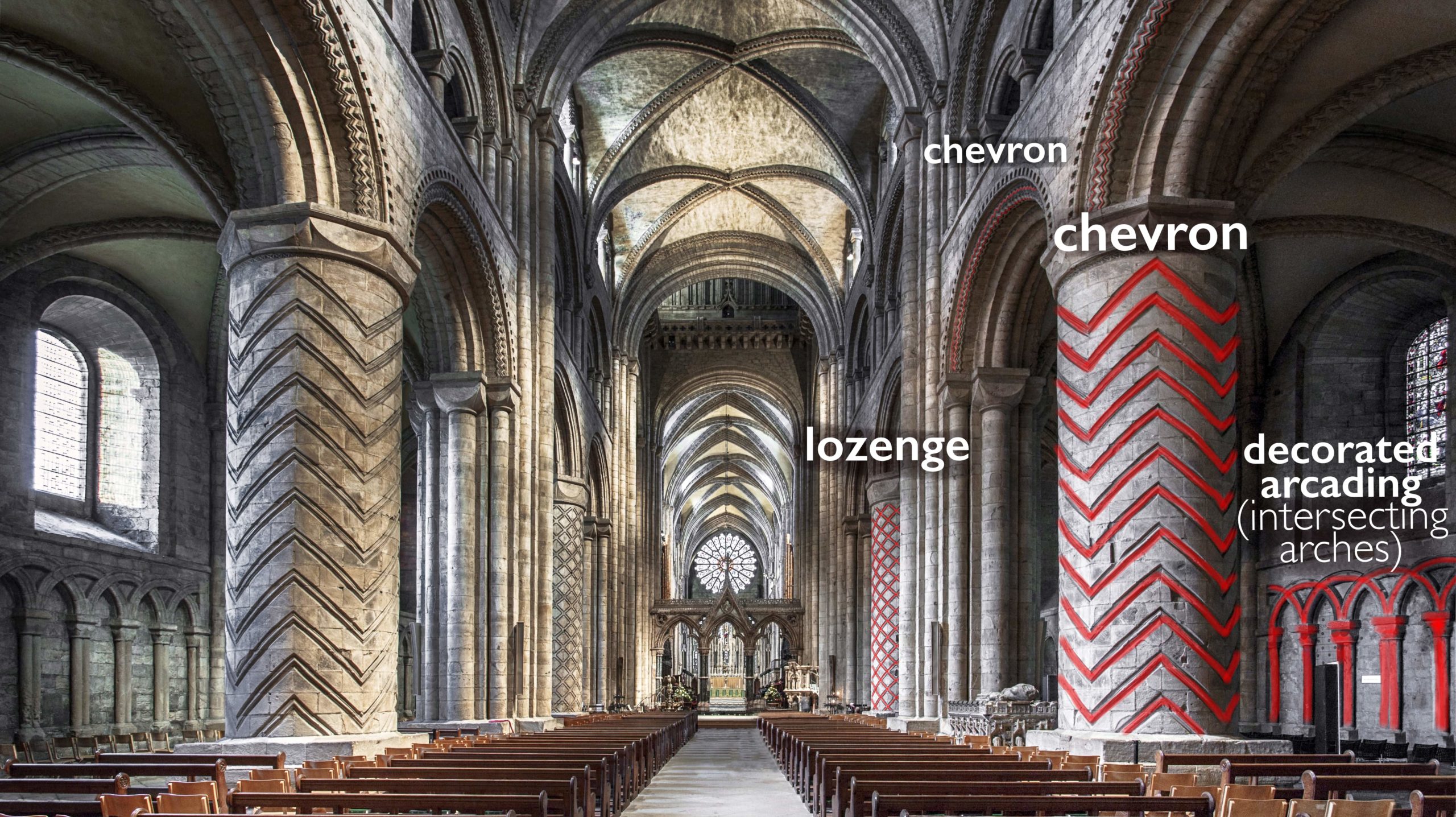

And yet, despite having the plan, the scale and elevation of a more or less classic Norman cathedral, Durham was also exhaustively dressed in a curious new kind of atypical sculpture. Bold linear carvings abounded: chevrons (or zigzags), lozenges, and even spirals.

Inside the cathedral there was scarcely any surface—from the vaults to the arcading to the piers—that was not extravagantly embellished in some way (whether by chisel or by brush). In fact, by almost every standard, not only of design but of execution—the proficiency of jointing and angling, the near metronomic consistency of stone cutting, as well as the sheer finesse and precocity of its ornamentation—the masons’ work at Durham looks as if belongs in an entirely different world.

Intersecting arches. Left: Great Mosque, Córdoba (9th–11th century); Aljafería in Saragossa (11th century); Durham Cathedral (12th century)

Precedents

Exactly which world has long been a matter for debate. Some art and architectural historians have made connections with earlier medieval Spain, Germany and France. The intersecting arcades at Aljafería in Zaragoza and, before it, the Great Mosque of Córdoba both make for intriguing alliances. Several cathedrals (including those at Mainz and Speyer) are interesting also for their shared size and extravagance. [2] None of these can be easily ignored (and I hesitate to rush through them). But there is still something like a broad if often quiet consensus that very few, if any, of these connections can be thought to be definitive (and certainly not singular influences) on Durham’s plan or execution.

Precisely where and/or when Durham’s masons derived any inspiration notwithstanding—and it’s probable, of course, that we’ll never know for sure—these analyses only stand to shed so much light on how and why these carvings actually functioned in practice. A better question might be: how they were encountered, how were they thought about by medieval men and women?

Spiral columns in the transept (Google Street View)

On the one hand, Durham’s uniquely elaborate surfaces could simply have been ornamental—that’s to say l’art pour l’art (art for art’s sake). It’s certainly been argued that the richer articulation of early medieval sculpture and painting was often commensurate with a desire to flaunt status or worth. Not insignificant therefore is the fact that the east end, the chancel, Saint Cuthbert’s shrine, his altar and the transepts—the spaces that most closely surrounded the saint’s remains—were the most ornate. Cuthbert, whose body was said to have been unearthed from its grave still flawless and even sweet-smelling (more than ten years after his death), was easily the most renowned saint in the north of England. The additionally lavish embellishment of his resting place may therefore have reflected a fitting relationship between decoration and dignity.

Arch in the cloister, Durham Cathedral (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

On the other hand, might these extraordinarily idiosyncratic forms also have embodied some kind of information or message, a means perhaps to communicate? Witnesses and evidence are in short supply, with a single shining exception. Symeon of Durham was a monk and, for some time, the Cantor at Durham Cathedral. He is one of fewer than a dozen people known to have been in attendance at the building’s ground-breaking in 1093 as well as the formal interment of St. Cuthbert’s body, just over a decade later. Symeon effectively alleged that the destruction of the old church, and this new church—with its reformed clergy—is what Cuthbert would have wanted all along. Perhaps like Symeon, the new cathedral’s masons (and he may have been one of them) were largely working without precedent towards the evocation of the architecture of Cuthbert’s ancient past.

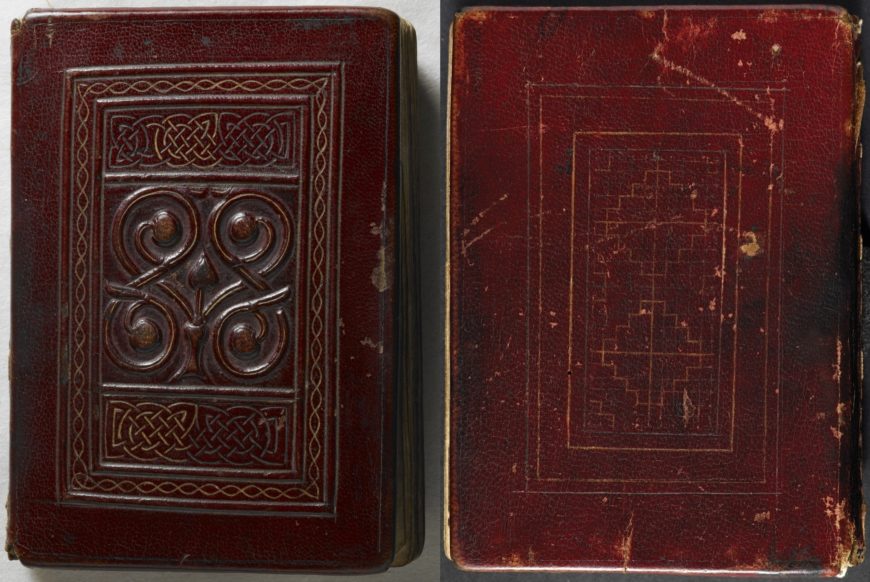

That being said, many other decorative motifs that did survive from seventh- and eighth-century Northumbria—the years during and immediately after Cuthbert’s lifetime—do share a similar and pronounced interest in the complex interplay of line, pattern and surface texture.

Carpet page for the Gosepl of Saint Matthew, Lindisfarne Gospels (British Library, MS Cotton Nero D.iv, fol. 26v)

The carpet page opening the Gospel of St Matthew in the early eighth-century Lindisfarne Gospels is a classic and exceptional example, as is, of course, the St Cuthbert Gospel itself. Having been placed in Cuthbert’s tomb in 698 on the occasion of his translation to the high altar at Lindisfarne (in Northumbria), this book and its original binding was unexpectedly found—or so the story goes—only eleven years after construction at Durham began. In the bold plastic articulation of the raised interlace on its upper cover, and especially in the schematic square settings of its lower cover it is easy to get a sense of a shared tradition.

Front and back cover, St. Cuthbert Gospel (British Library, Additional MS 89000)

Evoking an earlier, imagined medieval style?

Put another way, Durham’s strange new sculpted forms may appear familiar yet unspecific, evocative yet alien, or they might seem only loosely reminiscent of some kind of earlier medieval style—now as then—because they weren’t so much copied as they were imagined. If, like its southern counterparts—Canterbury (begun 1067), Winchester (begun 1079), Ely (begun 1079), St Augustine’s (begun c. 1080), or Old St Paul’s (begun 1087)—the massive chassis of Durham Cathedral did indeed function as something like its “hard” power then its interior fabric, its extraordinarily ornate surfaces, perhaps hinted at a much “softer” kind of meaning.

This extraordinary building is regularly described as a kind of brilliant late-Romanesque lynchpin, linking with and pre-empting the nascent proto-Gothic style in its use of pointed arches. On account of its sheer precision, its scale, its vaulting and—in particular—its precocious pointed ribs, Durham has come to represent a sparkling new apogee, not only to the first generation of post-Conquest building, but to a continent-wide narrative of “progressive” structural experimentation. Do bear all of these twentieth-century assessments in mind when you visit the cathedral. And yet, perhaps take at least one further moment to imagine how the twelfth-century masons at Durham may actually have spent much of their time looking, not to the new, nor to the future, but somewhat nostalgically to a very foggy and distant past.

Notes:

[1] For a modern translation, see Richard Gem, ‘The English Parish Church in the Eleventh and Early Twelfth Centuries: A Great Rebuilding?’, in Minsters and Parish Churches: The Local Church in Transition, 950-1200, ed. by John Blair (Oxford: Oxford University Press,1988), p. 21.

[2] Among other possible precedents are the columns painted in imitation of veined marble at Saint-Savin-sur-Gartempe (begun c.1050) and Saint-Hilaire-le-Grand (begun c.1050). Durham may also have shared a common prototype, now lost, with the small parishes of pre-Conquest Wittering (begun ca. 1050), Stow (begun ca. 1040), Great Paxton (begun ca. 1050), St Wystan’s (begun ca. 725), or St Botolph’s (begun 1020).

Additional resources

Durham Castle and Cathedral at UNESCO

Durham Cathedral: History Fabric and Culture, ed. by David Brown (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2015)

Anglo-Norman Durham, 1093–1193, ed. by David Rollason, Margaret Harvey and Michael Prestwich (Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer, 1994)

Medieval Art and Architecture at Durham Cathedral: The British Archaeological Association Conference Transactions for the Year 1977, ed. by Nicola Coldstream and Peter Draper (Leeds: British Archaeological Association Conference Transactions, 1980

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

[flickr_tags user_id=”82032880@N00″ tags=”durhamcathedral”]

[0:00] [music]

Dr. Steven Zucker: [0:04] We’re in Durham Cathedral, at the top of a hill in northeastern England. This is one of the great early cathedrals.

Dr. Beth Harris: [0:12] It’s built less than three decades after the Norman Conquest. That is, after William the Conqueror crossed the Channel with his army and invaded and took over England in a rather brutal invasion and replaced the old order of Anglo-Saxon England for this new Norman order, and built many churches, among the first of which is Durham Cathedral.

Dr. Zucker: [0:35] This location is at a bend in a river that is naturally fortified by a steep slope. The cathedral is built, as is the castle next to it, at this high point. It was built to contain the relics of an extremely important English saint, Saint Cuthbert.

Dr. Harris: [0:52] Cuthbert lived for a time on an island just off the east coast of England, in an area that was then called Northumbria. That island is called Lindisfarne, and you may have heard of it because one of the most beautiful of all early medieval illuminated manuscripts, the Lindisfarne Gospels, was produced at the monastery at Lindisfarne.

Dr. Zucker: [1:12] And was made to honor Saint Cuthbert and was transported with the remains of the saint from the island to this more protected area at a time when Vikings were threatening the coast.

Dr. Harris: [1:22] It might seem odd to be carrying around the body of a saint, but the body, the relics of Saint Cuthbert were incredibly important, they performed miracles. In fact, a shrine was built for Saint Cuthbert. It was gilded, it was covered in jewels.

Dr. Zucker: [1:41] Cuthbert developed a following that extended across the nation and even in the Continent. England had been taken by the Normans and was politically associated with that northern part of what we now call France.

Dr. Harris: [1:52] Normandy, and that’s where the Duke of Normandy, who invaded England in 1066, came from.

Dr. Zucker: [1:58] He brought with him not only his own bishops, not only his own nobility, but also building techniques from the Continent, so there was a continuity between Norman churches such as this one and the Norman churches that we see in northern France, which is why we call this style Anglo-Norman.

[2:15] English history is complicated. We have native peoples here that were conquered by the Romans, who then left in the early 5th century. The political vacuum was then filled by invaders from what is now southern Denmark and northern Germany. Peoples that we call the Angles and the Saxons, or the Anglo-Saxons.

Dr. Harris: [2:33] Then Anglo-Saxon England is supplanted by Norman England, and this is one of the first Anglo-Norman churches. And we feel the ancientness of this building. It is heavy. It feels fortified. In that way, we know that we’re standing in a Romanesque church.

Dr. Zucker: [2:53] This was some of the earliest large-scale architecture to take place since the Romans had left. We call it Romanesque because this architecture was dependent on the technology that the Romans had originally used. That is, the round arch.

Dr. Harris: [3:06] One of the things that one notices immediately is how decorative the surfaces are. That is a key feature of Anglo-Norman Romanesque that differentiates it from what was going on on the French continent.

Dr. Zucker: [3:18] We’re standing in the nave, and we’re surrounded by these massive piers that hold up the heavy vaulting above us. There are basically two types of piers that alternate. One is a simple cylindrical pier and the other is a more complex and larger compound pier that has attached columns.

Dr. Harris: [3:37] Those cylindrical piers are the ones that carry this amazing linear decoration. When we walk in from the west end, we see fluted columns. As we make our way east toward the holiest end of the church, we see cylindrical piers decorated with chevrons, these zigzag shapes. Then we come upon lozenge shapes, in each case really deeply cut, creating dark shadows that were likely originally painted.

Dr. Zucker: [4:05] If you look closely, you’ll notice that, ingeniously, the stonemasons created a kind of mass production. Each stone is identical to another. And yet, when they fit together, they create these continuous patterns.

Dr. Harris: [4:16] This is a testament to the increasing skill of stonemasons during the Romanesque period.

Dr. Zucker: [4:22] As we move eastward, we see massive spiral columns, which reflect the spiral columns at St. Peter’s in Rome, surrounding the tomb of St. Peter. Here, the columns are closer to the tomb of Saint Cuthbert, creating a correspondence between Cuthbert and Peter.

Dr. Harris: [4:39] Also, the dimensions of this church are very close to the dimensions of Old St. Peter’s. That was a very common thing in medieval architecture, to emulate important precedents, like St. Peter’s, or important churches in Jerusalem.

Dr. Zucker: [4:54] The interior elevation is three-part. Above the nave arcade is this broad, heavy gallery.

Dr. Harris: [5:00] I’m struck by the depth of the archway and the rolls of molding that lead our eye up to that gallery. We can see that in some cases that molding is decorated with that chevron zigzag pattern in these wonderfully complex ways.

Dr. Zucker: [5:18] We see that chevron zigzag everywhere in this church. It creates the most lively pattern that activates the surfaces of stone.

Dr. Harris: [5:26] The church is relatively dark, as most Romanesque churches are. We can see a clerestory, which is rather small. Interestingly, those windows are slightly inset. Again, we have a sense of the depth of the wall.

Dr. Zucker: [5:40] There is in fact a narrow walkway that moves just in front of those windows.

Dr. Harris: [5:45] This idea of emphasizing the depth of the wall, this interest in decorative carving, these are all things that art historians see as carrying through after the Romanesque into the English Gothic.

Dr. Zucker: [5:57] One of my favorite decorative aspects of the church can be seen in the aisles. We see these doubled attached columns with these interlacing arches just above. It’s almost musical.

Dr. Harris: [6:07] We have to imagine these painted in reds, greens, and yellows, so they would have really stood out. Art historians believe that these might be influenced by the art of Islamic Spain.

Dr. Zucker: [6:19] For example, in the Great Mosque at Córdoba we see interlacing similar to this. An aspect of this church that fascinates art historians is the vaulting, because here we see the precocious early use of ribbed vaulting.

Dr. Harris: [6:31] Ribbed vaulting does, in some form, go back to the ancient Romans, but its use here is very important because we know what’s going to follow in the Gothic.

Dr. Zucker: [6:40] Before stone vaulting, churches had been covered with wood, sometimes even flat wood ceilings. Not only was stone vaulting more fireproof, it allowed for a shaping of space that was far more decorative.

Dr. Harris: [6:52] If we follow the lines of the vault, we notice that it leads our eye down a shaft which is attached to the compound pier. You have this unifying of the nave from the ground all the way up through and across the transverse arch that takes us to the other side of the nave. This unification of space is something that will become very important in the Gothic era.

Dr. Zucker: [7:16] We’ve entered the Galilee. This was built after the main church was completed, and architecturally, it’s a completely different space.

Dr. Harris: [7:24] Here, instead of those very massive, heavy cylindrical columns or those massive compound piers, we have sets of four columns joined together that feel very light. The space feels very open.

Dr. Zucker: [7:38] It was possible because this part of the church does not have heavy stone vaulting. Instead, we have a wooden roof, and so the architect could afford to use these delicate, slender columns.

Dr. Harris: [7:49] They carry arches that are decorated, again, with these incredibly deep and complex chevron patterns.

Dr. Zucker: [7:56] Here, because the ceiling is lower, they’re closer to us and they really activate the space. The entire space almost feels electrified.

Dr. Harris: [8:04] There is significant wall space above the arches. Much of that was, it seems, covered with paintings. Some of them just barely survive along one of the aisles.

Dr. Zucker: [8:15] We think this is the first Galilee attached to a church in England.

Dr. Harris: [8:19] We know that these spaces were used as gathering places, perhaps, at the start of a liturgical procession. The word “Galilee” is a reference to Christ’s entry in Jerusalem, because when he entered Jerusalem, he came first from Galilee.

[8:34] We’ve left Durham Cathedral and heading back to the train station, taking a view of both the cathedral and the castle and the river that surrounds them. We’re reminded of Saint Cuthbert himself, who chose this very strategic location.

Dr. Zucker: [8:50] At least according to legend. As his remains were being carried on a cart, the cart stopped not far from here.

Dr. Harris: [8:57] As though this was directed by the saint himself.

Dr. Zucker: [9:00] And then thanks to a vision that had to do with a brown cow, this sacred spot was found.

Dr. Harris: [9:05] I’m so glad this Norman castle and cathedral have stood the test of time.

[9:10] [music]