Skunder (Alexander) Boghossian, Night Flight of Dread and Delight, 1964, oil on canvas with collage, 56 5/8 x 62 5/8 in. (143.8 x 159.1 cm) (North Carolina Museum of Art, Raleigh, Purchased with funds from the North Carolina State Art Society (Robert F. Phifer Bequest), 98.6; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

“African art created a condition in my mind. I learned that creation must be an immense and unceasing modulation of concept.”—Skunder Boghossian (1965) [1]

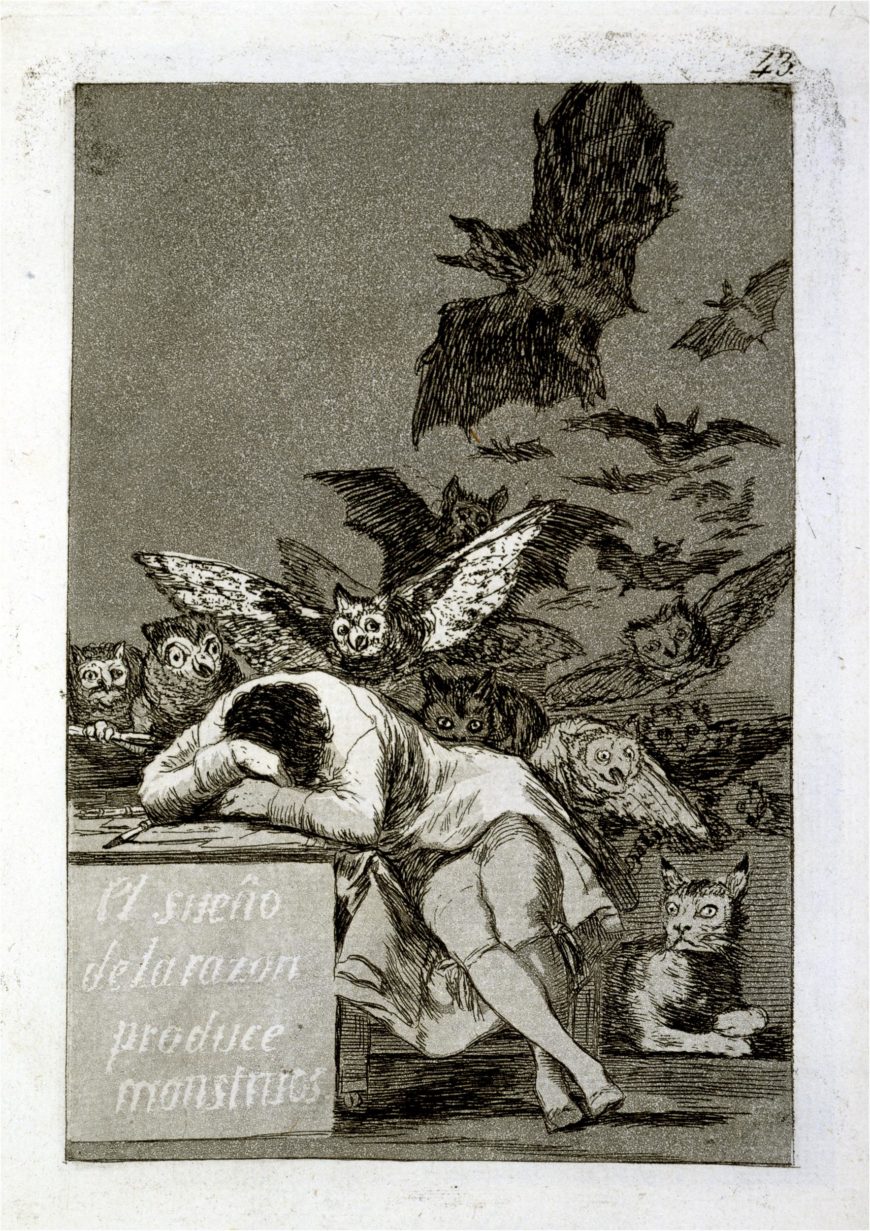

Francisco de Goya, Los Caprichos: The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters, 1799, etching and aquatint, 21.2 x 15.0 cm (British Museum, London)

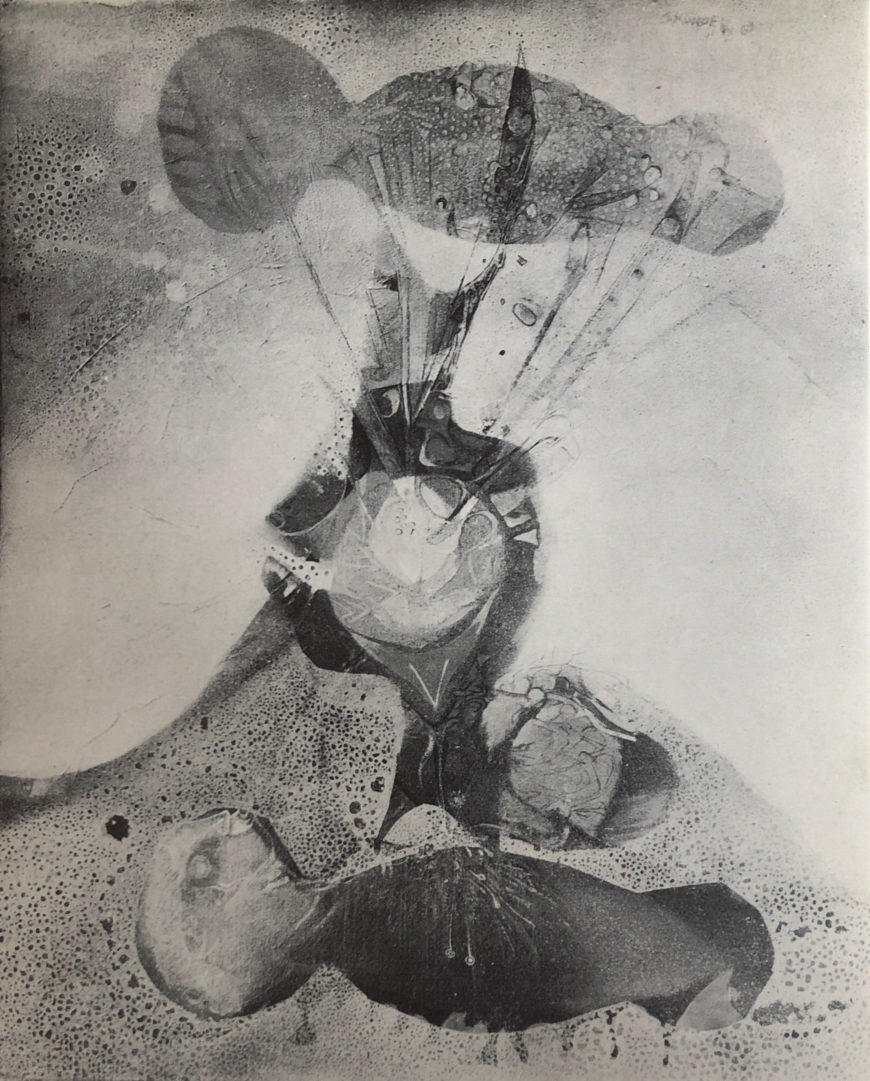

In his 1964 painting Night Flight of Dread and Delight, Ethiopian artist Skunder Boghossian divides the composition in two with a boundary line that represents the separation of the earth from the heavens. Two wide-eyed, winged creatures, one with the face of a cat, another an owl, echo the monsters conjured in Francisco Goya’s etching The Sleep of Reason and breach the barrier between realms. Haunting biomorphic and cosmic forms emerge and retreat from the depths of space, and paint splatters seem to pulse like dark matter. Noting the primordial duality to which this composition refers, Boghossian’s close friend, the Ethiopian writer and poet Solomon Deressa, commented that “The vision menaces and delights at the same time. Images both attack and yet remain connected. Subdued colors are exploded from within their dark nether until they become shimmering jewels.” [2]

In works such as Night Flight, Boghossian aspired to use painting to represent the metaphysical world, imagining the universe beyond normal human perception. Metaphysics refers to the study of abstract concepts like being, knowing, identity, time, and space. Shaped by a deep interest in pan-African cosmologies, histories, iconographies, knowledge systems, and politics, Boghossian’s art is an expression of “afro-metaphysics.” He formally and conceptually investigated spiritual and historical knowledge from traditions as diverse as Dogon cosmology from Mali and the Ethiopian Orthodox Church. His art freely subjected their forms to new pictorial relationships that reflected the postcolonial reality of the mid-1960s.

Skunder (Alexander) Boghossian, detail of winged creature with a cat’s face, Night Flight of Dread and Delight, 1964, oil on canvas with collage, 143.8 x 159.1 cm (North Carolina Museum of Art; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

A pioneer of African modernism, Boghossian drew upon pan-African visual languages and references, from Coptic art and West African sculpture to the magical realist literature of Nigerian writer Amos Tutuola, to give form to both visible and invisible realities in his paintings. He manipulated symbolic and spiritual visual and literary traditions to picture the metaphysical world. In Boghossian’s hands, each of Night Flight’s animal subjects become worlds unto themselves, with a universe of graphic patterns, talismanic designs, and amoebic forms proliferating within their porous boundaries. Night Flight is a cosmological painting enabled by the artist’s study of wide-ranging global artistic traditions during the formative years he spent in Paris, from 1957 to 1966.

Skunder (Alexander) Boghossian, detail, Night Flight of Dread and Delight, 1964, oil on canvas with collage, 143.8 x 159.1 cm (North Carolina Museum of Art; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Pan-African Paris

“I grew up in the streets of Paris, I had no problem being black or yellow or green. I learned my craft.”—Skunder Boghossian (1999) [3]

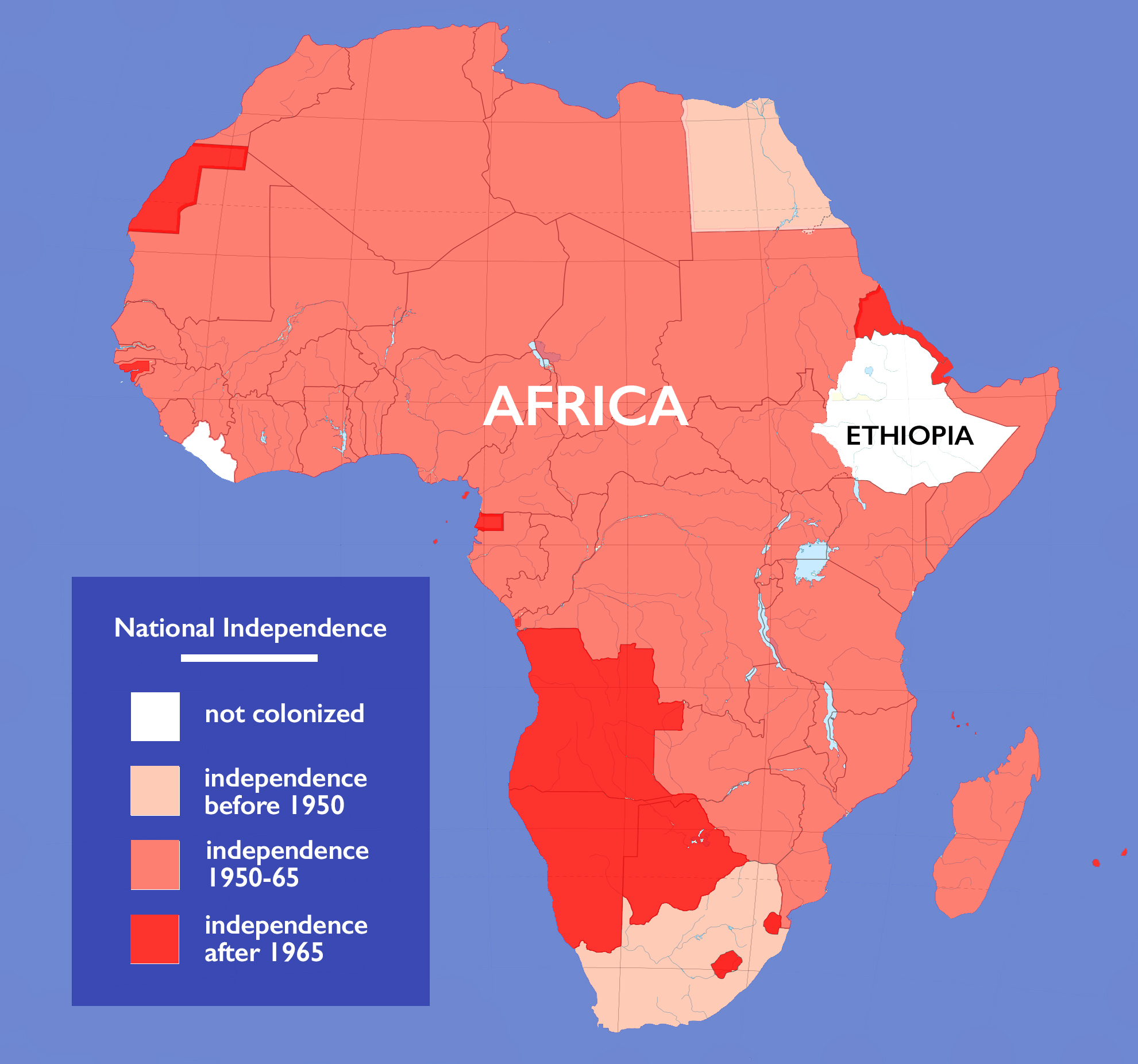

Map of the end of colonial rule. in Africa (base map: Eric Gaba, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Pan-Africanism refers to an ideology of racial solidarity among people from Africa and its diaspora. Ethiopia holds a prominent place within the Pan-African imagination as an ancient African nation that was able to successfully resist colonization. Still, Skunder Boghossian’s childhood there was marked by colonial trauma. The artist was born in the Ethiopian capital Addis Ababa in 1937 during Italian dictator Benito Mussolini’s occupation of the country two years before the outbreak of World War II. While the artist was still an infant, his father was taken to Italy as a prisoner of war; he was not repatriated until Boghossian was eight years old. As a youth, Boghossian won a scholarship from Emperor Haile Selassie I to study art in London. Two years later, in 1957, Boghossian relocated to Paris and remained there until 1966 when he moved back to Addis Ababa to teach at the university alongside the prominent Ethiopian modernist Gebre Kristos Desta.

In Paris, Boghossian encountered art and individuals who shifted his artistic practice towards a sustained inquiry into both European modernism and African artistic traditions. He became enmeshed with the Black intelligentsia in Paris, engaging with modernist artists like Ibrahim El-Salahi (Sudan), Wifredo Lam (Cuba), Gerard Sekoto (South Africa), and Merton Simpson (United States); the political and cultural leaders of the Négritude movement; and the liberating improvisation of global jazz musicians.

Négritude was first developed as a concept in Paris in the late 1920s by three Black students from French colonies in West Africa and the Caribbean—Aimé Césaire from Martinique, Léon Damas from French Guiana, and Léopold Senghor from Senegal. It was a political and philosophical movement that affirmed the value of Black civilization to counter and refuse its denigration by colonial powers. Boghossian’s participation in Négritude circles in Paris encouraged him to explore African heritage, history, and culture beyond his native Ethiopia. He studied African art at the ethnographic Musée de l’homme at the Trocadéro in Paris, and became inspired by the forms and meanings of Dogon and Bwa masks from West Africa, Oromo and Konso sculpture from Ethiopia, and ancient Nubian, Aksumite, and Ethiopian Christian imagery.

Skunder Boghossian, Hallucination, oil on canvas, 1961. 39 x 25 1/16 in. (Gift of Merton Simpson in memory of Sylvia H. Williams, Smithsonian National Museum of African Art)

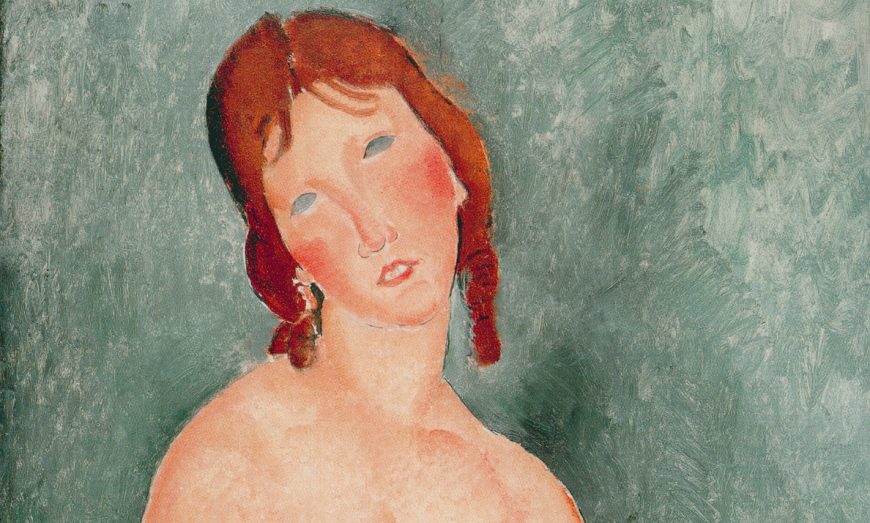

Boghossian also studied the work of European modernists who engaged African art forms, like Amedeo Modigliani (Italy), Paul Klee (Germany), and the leader of the surrealist movement, André Breton. Like his fellow postcolonial modernist artists, including Uche Okeke, Ibrahim El-Salahi, and others, Boghossian’s interest in European modernism deliberately confronted and revealed its primitivist origins. In the early 1960s, Boghossian worked in the figurative style seen in his painting Hallucination from 1961 that demonstrates—with its elongated features, sloping shoulders, and three-quarter length focus on a single subject—his interest in Modigliani’s portraits.

Memorial Head (Nsodie)

17th–mid-18th century, Akan peoples, terracotta, roots, quartz fragments, 20.3 × 14 × 12.1 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

His subject’s prominent brow and eyes, rounded facial shape, ringed neck and decorative background also call to mind 17th- to 18th-century terracotta Akan memorial heads known as nsodie from present-day Ghana and Ethiopian illuminated manuscripts. Boghossian self-consciously combined multiple visual traditions from different points in history to comment on the breadth of African art’s influence on global modernist art movements. Boghossian exhibited similar figurative paintings from this period in New York during his 1962 visit there that earned him attention among American audiences.

Skunder Boghossian, Explosion of the World Egg, from the Nourishers series, oil on paper, 1963, dimensions unknown

Upon his return to his studio in Paris, his earlier encounters with the surrealist strategies of fragmentation and imaginative reassembling began to take shape and expanded the formal and conceptual possibilities Boghossian saw for his own work. His experimental Nourishers series, begun in 1963, marked a shift in his formal style. He began to subject the varied artistic, philosophical, and religious traditions he had studied to new pictorial relationships informed by surrealism by creating complex collage-like compositions that defy the legibility of his earlier figurative paintings.

Produced in the wake of independence movements across Africa, paintings like Explosion of the World Egg from the Nourishers series used primal, organic forms and cosmic patterns to convey themes of rebirth and new life that symbolized the promise of postcolonial Pan-Africanism. The primordial egg at the heart of this painting reappears in Night Flight, a recurrent symbol of the hope for Pan-African liberation that accompanied independence in the 1960s.

Skunder Boghossian, Juju’s Wedding, tempera and metallic paint on cut-and-torn cardboard, 1964. 21 1/8 x 20 in. (Museum of Modern Art)

The Black Atlantic

Boghossian’s exposure to Pan-Africanist networks in Paris gave conceptual weight to the formal experiments that culminated in his painting Night Flight of Dread and Delight. The painting fully engaged the artist’s developing philosophy of “afro-metaphysics” that drew on the power of religion and myth and prefigured afrofuturism in art, music, and literature. Boghossian often referred to “juju” as a shorthand for this philosophy. In fact, an alternate title for Night Flight used by Solomon Deressa, who often provided Boghossian’s paintings their poetic titles, is Juju’s Flight of Delight and Terror. The term also shows up in a related work from this period, Juju’s Wedding.

Skunder (Alexander) Boghossian, Night Flight of Dread and Delight, 1964, oil on canvas with collage, 56 5/8 x 62 5/8 in. (143.8 x 159.1 cm) (North Carolina Museum of Art, Raleigh, Purchased with funds from the North Carolina State Art Society (Robert F. Phifer Bequest), 98.6; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Though Boghossian first developed his new pan-African philosophy in Paris, it fully emerged across the Atlantic Ocean, in Tuskegee, Alabama in the heart of the American South during the height of the Civil Rights Movement. Boghossian produced Night Flight and other important paintings and sculptures in the productive months following his August 1964 wedding in Tuskegee to Marilyn Pryce, an American student and Civil Rights activist he met in Paris, whose father worked at the historic Tuskegee Institute (now Tuskegee University). [4]

Skunder Boghossian, Ghosts of the Atlantic Ocean, opaque watercolor, acrylic and ink on paper board, 1964. 27 5/8 x 40 1/4 in. (Hampton University Museum)

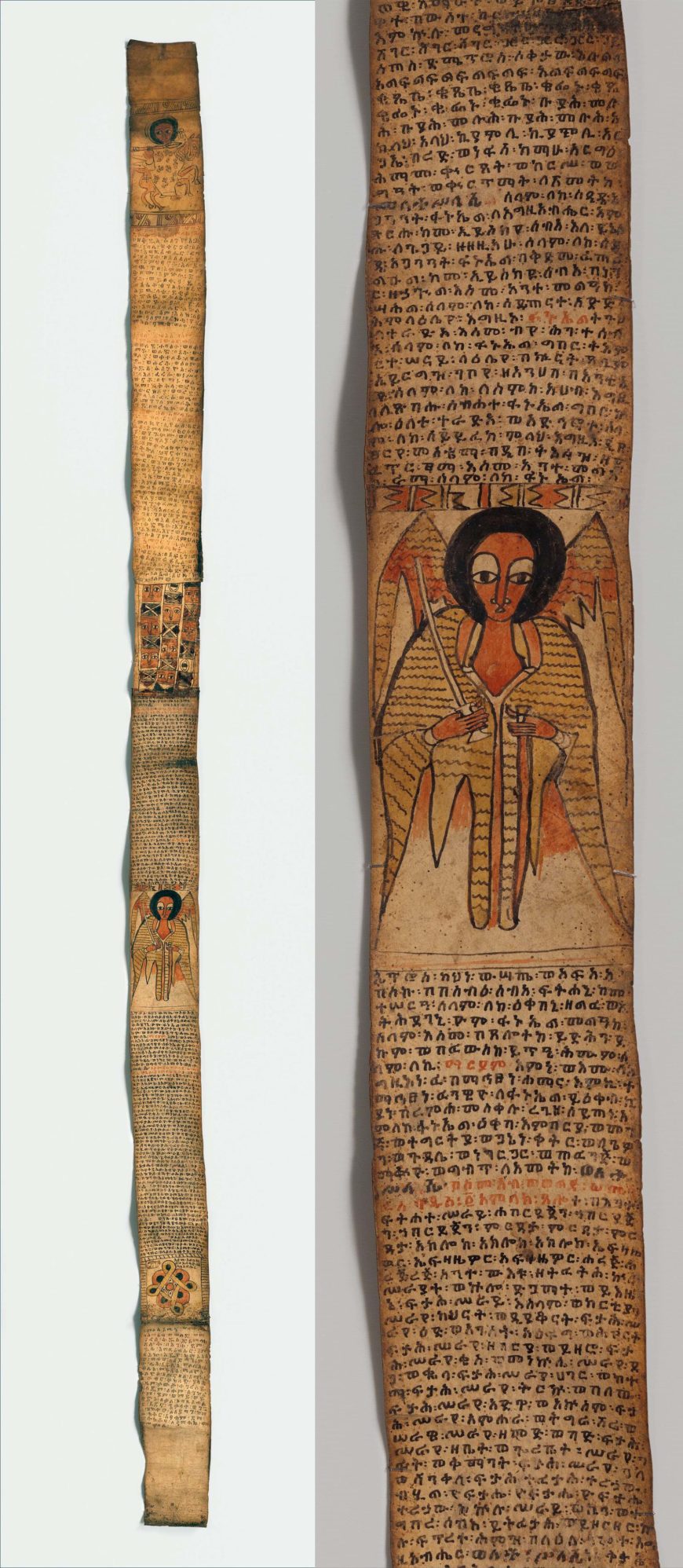

Amhara or Tigrinya peoples (Ethiopia), Healing Scroll, 19th century; detail on the right, pigment on parchment, 3-1/2 x 75 inches (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Reflecting Boghossian’s own Black diasporic experience, Night Flight visualizes the feeling of being between worlds. Produced in the wake of a terrifyingly turbulent flight from Paris to New York the month before his wedding, on the surface, the work meditated on real experience and anxiety. But it also refers to a deeper legacy of Black trauma perpetrated during the violent trans-Atlantic voyages of the slave trade. In his 1964 painting Ghosts of the Atlantic Ocean, Boghossian more pointedly mourned the lives lost to the Middle Passage and addressed the unresolved histories of oppression. Just as Night Flight sought to visualize the cosmic expanse of the extraterrestrial universe, Ghosts examines the infinite and unknown worlds trapped beneath the sea’s surface. Boghossian again repeats and combines recognizable designs and forms from across Africa, including the black and white geometric patterns of Bwa masquerades from present-day Burkina Faso and the abstracted horns and circular face of Goli masquerades made by Baule peoples in Côte d’Ivoire to preserve the potency of the visual and cultural traditions that slavery and colonialism threatened to erase.

Both Night Flight and Ghosts reveal the artist’s longstanding formal and compositional experiments with Ethiopian healing scrolls, which surface in Boghossian’s paintings as strips that disrupt his compositions and as formal elements like winged creatures or talismanic designs. In Boghossian’s hands, these narrow vertical scrolls used to treat sickness through textual incantations and graphic design are invoked to heal historical trauma.

In 1970, after three years back in Addis Ababa, Boghossian resettled, this time permanently, in the United States, where he taught art at the famed Howard University in Washington, D.C. and became involved in the Black Arts Movement (an African American-led art movement, active during the 1960s and 1970s). Boghossian’s time in the United States deepened his awareness of the shared histories, politics, and cultures that shape global Black experience.