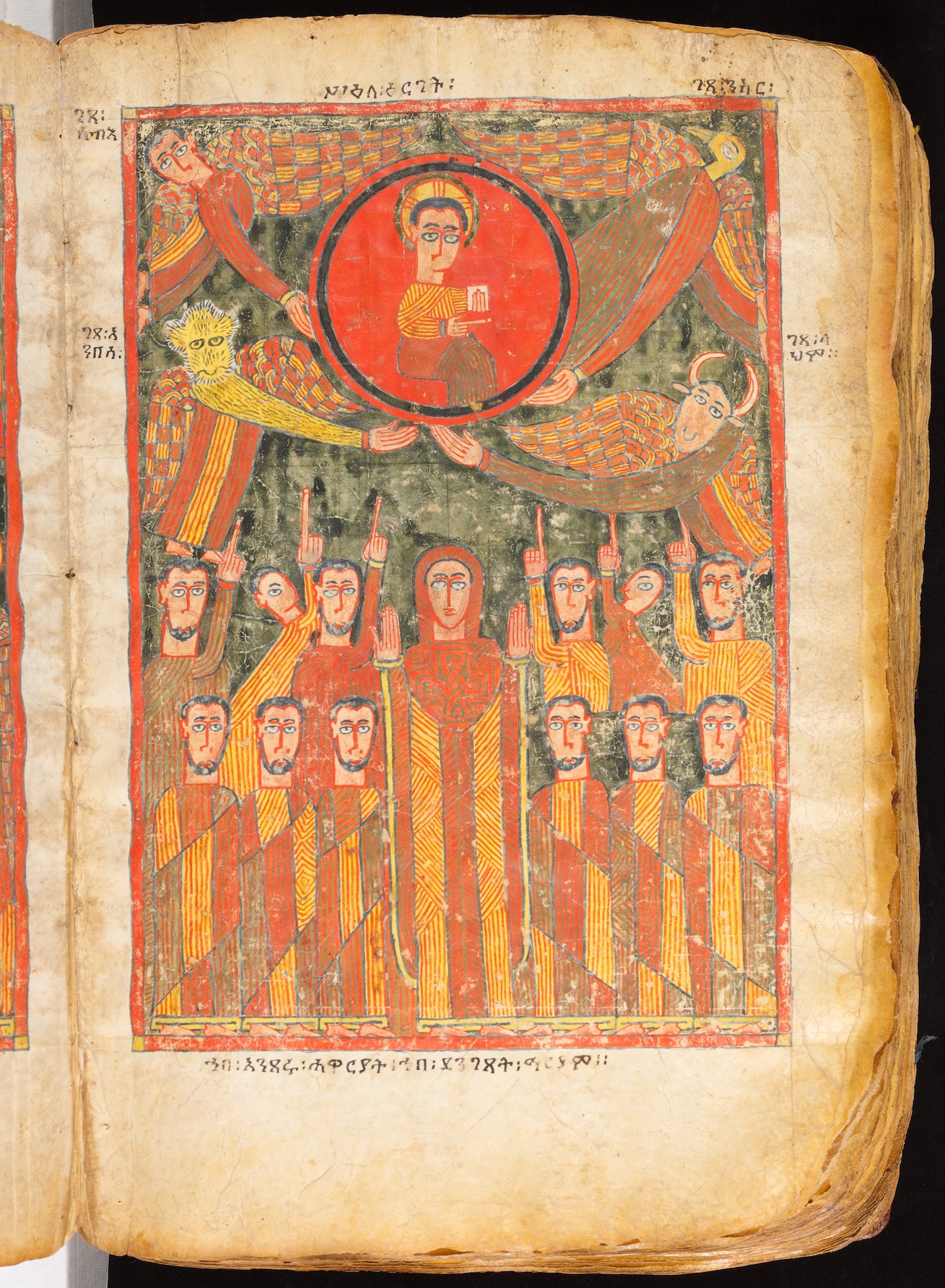

Illuminated Gospel, Amhara peoples, Ethiopia, late 14th–early 15th century, parchment (vellum), wood (acacia), tempera and ink, 41.9 x 28.6 x 10.2 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

This full-page illumination is one of twenty-four from a manuscript of the Gospel that reflects Ethiopia’s longstanding Christian heritage. The Ethiopian Orthodox Church was established in the fourth century by King Ezana. He adopted Christianity as the official state religion of Aksum, a kingdom located in the highlands of present-day Ethiopia. As the Christian state expanded over the centuries, monasteries were founded throughout the region. These became important centers of learning and artistic production, as well as influential outposts of state power.

The manuscript was created at a monastic center near Lake Tana in the early fifteenth century. It is composed of 178 leaves of vellum bound between acacia wood covers. The illuminations depict scenes from the life of Christ and portraits of the Evangelists. This text and its pictorial format are based upon manuscripts produced by the Coptic Church. Here, however, these prototypes are transformed into local forms of expression. For example, the imagery is two-dimensional and linear, which is characteristic of Ethiopian painting. Additionally, the text is inscribed not in its original Greek, but in Ge’ez, the ancient liturgical language of Ethiopia. Ge’ez is one of the world’s oldest writing systems and is the foundation of today’s Amharic, Ethiopia’s national language.

Christ (detail), Illuminated Gospel, Amhara peoples, Ethiopia, late 14th–early 15th century, parchment (vellum), wood (acacia), tempera and ink, 41.9 x 28.6 x 10.2 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

In this depiction of the Ascension of Christ into heaven, he appears framed in a red circle at the summit, surrounded by the four beasts of the Evangelists.

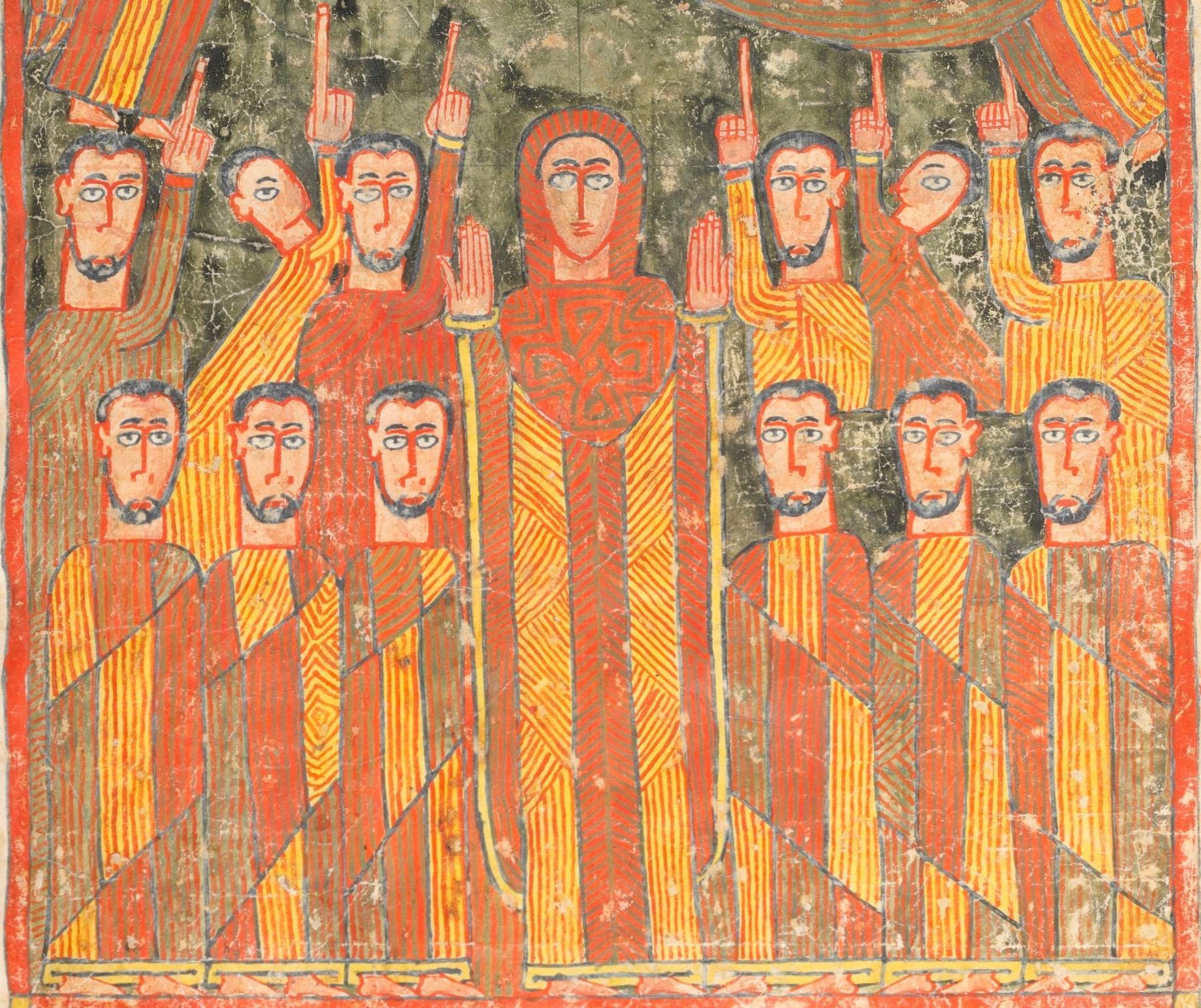

Mary and the apostles (detail), Illuminated Gospel, Amhara peoples, Ethiopia, late 14th–early 15th century, parchment (vellum), wood (acacia), tempera and ink, 41.9 x 28.6 x 10.2 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

Below, Mary and the Apostles gesture upward. The stylistic conventions seen here, such as the abbreviated definition of facial features and boldly articulated figures, are consistent throughout the manuscript, suggesting the hand of a single artist. The artist depicts the figures’ heads frontally and their bodies frequently in profile. The use of red, yellow, green, and blue as the predominant color scheme is typical of Ethiopian manuscripts from this period. The images were intended to be viewed during liturgical processions.

The Gospels were considered among the most holy of Christian texts by the Ethiopian Orthodox Church. Such manuscripts were often commissioned by wealthy patrons for presentation as gifts to churches. While the text demonstrated the erudition of its monastic creator, the elaborate ornamentation reflected the prestige of the benefactors. Many works of Ethiopian art were destroyed by Islamic incursions during the sixteenth century, making this manuscript a rare survivor.

© 2006 The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (by permission)