Melchor Pérez de Holguín, Entry of Viceroy Archbishop Morcillo into Potosí, 1716, oil on canvas, 240 x 570 cm (Museo de América, Madrid)

In this painting, a man of importance and his retinue enter a city through an elaborately decorated arch (seen on the far right). A crowd of soldiers, attendants, and clerics surround this important individual, who is seated under a baldachin (ceremonial canopy) to indicate his status. People peek out of windows to watch the elaborate event that we see unfolding in three different moments of time in the famous Andean “silver city” of Potosí that produced incalculable amounts of silver for the Spanish Crown during the colonial period (c. 1534–1820). The procession moves across the canvas, with events unfolding in different parts of the city within two inset scenes at the top center and left.

Melchor Pérez de Holguín represents the triumphal entry of Viceroy Archbishop Diego Morcillo Rubio de Auñón, who was a colonial official and bishop in the Viceroyalty of Peru. With his careful attention to detail and his desire to capture the city at its peak, Pérez de Holguín conveys the wealth and splendor of this jewel of the Spanish Crown and the elaborate fanfare with which Morcillo’s entry in 1716 was met. Morcillo had come from elsewhere in the viceroyalty to the more remote city of Potosí to make his entrance.

Conquistador Francisco Pizarro had led Spanish forces to invade what is now known as Perú in 1531, and for the next four decades, Spanish conquistadors continued to wage war against the Indigenous people and the powerful Inka Empire as they established the Viceroyalty of Peru. High in the Andes Mountains, the city of Potosí was founded in 1545 after a large vein of silver was discovered in the mountain that would be named the “Cerro Rico,” or the “Rich Hill.” People flocked to the city, transforming it into the gem of the Andes—at least for a time. While the magnitude of silver mining is unknown, locals contend that Spaniards could have built a silver bridge from Potosí (in Bolivia today) to Madrid and still have silver to carry over. By 1573, Potosí was one of the largest cities in the world, and by the seventeenth century Potosí became a glittering urban marvel.

Right side of the painting showing the triumphal arch under which the Viceroy Archbishop Morcillo and his retinue pass. The viceroy is under a baldachin. Melchor Pérez de Holguín, Entry of Viceroy Archbishop Morcillo into Potosí (detail), 1716, oil on canvas, 240 x 570 cm (Museo de América, Madrid)

A triumphal entry

In the Spanish Colonial world, the triumphal entries (entradas in Spanish) of viceroys in major cities were a display of propaganda and political allegiances, and had a long history in Europe dating back to the Middle Ages. The viceroy was considered a stand-in for the King of Spain and was treated with the fanfare and pageantry upon entering a city as would be expected of royalty. Morcillo’s entrada into Potosí in 1716 was such an important event that colonial officials from all over the Viceroyalty of Peru came to watch the pageantry and power on display. Chroniclers recorded it in great detail, and Pérez de Holguín captured it in paint. [1] Pérez de Holguín, who lived in Potosí, recorded the events in a continuous narrative across three scenes: the viceroy entering the city, his reception by political and church leaders in the main square, and the evening festivities that followed.

This painting was most likely commissioned by Don Francisco Gambarte, a successful local businessman and elite member of the community. The intended audience were powerful potosinos (people who lived in Potosí) who would have understood the work as a symbol of the influence and prestige of their city.

An example of a processional painting. Anonymous Cusco artist, Procession of Corpus Christi, c. 1700–1800 (Museo Pedro de Osma)

The procession

Processional paintings were a common form of colonial Peruvian art. Works showing the procession of Corpus Christi show similar processional traditions as those in Potosí in colonial Peruvian cities: elaborate baldachins, streets decorated with tapestries and paintings, and well-dressed citizens lining the processional route. The Entry of Viceroy Archbishop Morcillo into Potosí, however, does not show a religious procession, but the entry of a political figure into a remote but important city in his dominion.

Right side of the painting showing the triumphal arch under which the Viceroy Archbishop Morcillo and his retinue pass. The viceroy is under a baldachin. Melchor Pérez de Holguín, Entry of Viceroy Archbishop Morcillo into Potosí (detail), 1716, oil on canvas, 240 x 570 cm (Museo de América, Madrid)

The main register shows the Viceroy’s retinue wearing the finest fashion of the day, greeted with a triumphal arch at the city’s wall, covered in gold, paintings, and large statues of the archangels: all allusions to the power of the Spanish Crown. In the Spanish American colonies, as in Spain, walking under a triumphal arch was a privilege reserved only for the holders of high office. [2] The viceroy travelled under an embroidered silk baldachin with golden fringe. The arrival of a viceroy, especially to a remote city like Potosí, was a rare and celebrated occurrence and no cost would be spared to mark the occasion, both to underscore the colonial power of the Spanish administration and to impress upon the viceroy the wealth, culture, and patriotism of the city’s population.

Potosinos watching the procession; banners and paintings hang from balconies and walls along the route. Melchor Pérez de Holguín, Entry of Viceroy Archbishop Morcillo into Potosí (detail), 1716, oil on canvas, 240 x 570 cm (Museo de América, Madrid)

Along the processional route in the main scene, potosinos line the streets and peer out of buildings to catch a glimpse of the cavalcade as it moves to the center of the city. Women are shown wearing their finest clothes and jewels, although they do not take an active part in the procession or the celebrations that follow. The street is decorated with banners and allegorical paintings referring to virtues the Spanish colonizers expected their subjects to embody. Scenes showing classical mythology such as Icarus and Daedalus, Eros and Anteros, and Mercury and Argos speak to humility or warn against unrequited love or deceit, and are decidedly Eurocentric understandings of how one should act.

Top left register of Melchor Pérez de Holguín, Entry of Viceroy Archbishop Morcillo into Potosí (detail), 1716, oil on canvas, 240 x 570 cm (Museo de América, Madrid)

In the inset at the top left, we see Morcillo welcomed into the city center. Pérez de Hoguín has labeled significant buildings around the main plaza (see the annotated image below), such as: the mint (Casa de la Moneda), emphasizing the city’s economic importance in the colony; the Casa del Corregidor, where the corregidor (a Spanish colonial official) served in his administrative and judicial function over the city; and the carcel, or jail, demonstrating the officials’ dedication to enforcing colonial law.

Top left register of Melchor Pérez de Holguín, Entry of Viceroy Archbishop Morcillo into Potosí (detail), 1716, oil on canvas, 240 x 570 cm (Museo de América, Madrid)

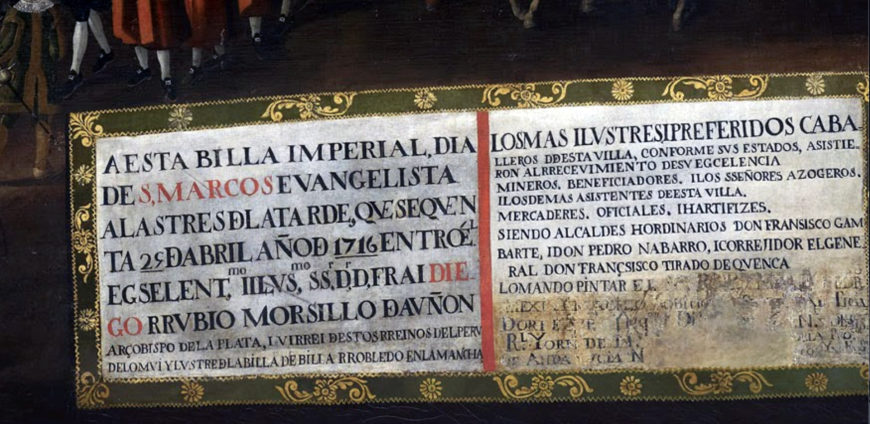

Inscription in the lower right, Melchor Pérez de Holguín, Entry of Viceroy Archbishop Morcillo into Potosí (detail), 1716, oil on canvas, 240 x 570 cm (Museo de América, Madrid)

The use of text within the painting allows the artist to not only provide important historical context, but capture the character of the city and its place within the Spanish colonial world. In the lower right, a caption speaks to the ceremony not only in describing the day, but also enumerating all of Morcillo’s titles and honors. In this caption, Pérez de Holguín also names the colonial officials who welcomed Morcillo into the city: Don Francisco Gambarte, and Don Pedro Navarro, as well as Don Francisco Tirado, the corregidor of the Andean city of Cuenca (present-day Ecuador).

Top center register of Melchor Pérez de Holguín, Entry of Viceroy Archbishop Morcillo into Potosí (detail), 1716, oil on canvas, 240 x 570 cm (Museo de América, Madrid)

In the top center inset scene, Morcillo is seated under a light pink baldachin, on a wheeled platform, while a parade of important figures dressed as knights, Moors, and Inka royalty entertain the crowd.

Morcillo’s coat of arms. Melchor Pérez de Holguín, Entry of Viceroy Archbishop Morcillo into Potosí (detail), 1716, oil on canvas, 240 x 570 cm (Museo de América, Madrid)

Pérez de Holguín pays homage to the Viceroy by including Morcillo’s family coat of arm at the center of the painting and an angel carrying the papal crown, which symbolizes the Pope’s blessing of both the procession and Morcillo’s leadership.

Conversation between an elderly couple. Melchor Pérez de Holguín, Entry of Viceroy Archbishop Morcillo into Potosí (detail), 1716, oil on canvas, 240 x 570 cm (Museo de América, Madrid)

The artist includes some humor in the procession, showing an older couple remarking on the festivities. The conversation is recorded in snaking, gold text. The old man asks: “Hey girl, when’s the last time you saw such a marvel” (Hija, tilonga has bisto esta marabilla). The woman, pointing at the procession, answers: “I swear, I have not seen anything so grand for more than one hundred years” (Alucha en ciento y tanto años no e bisto grandeza tamaña).

A self-portrait of the artist above his signature. Melchor Perez de Holguin, Entry of Viceroy Archbishop Morcillo into Potosí (detail, 1716, oil on canvas, 240 x 570 cm (Museo de América, Madrid)

The artist has also included his own self-portrait next to his signature. By emphasizing his presence at the events, Pérez de Holguín implicitly attests to their accuracy, reminding the viewer that he was there and experienced the events first-hand. Still, it is important to remember that Pérez de Holguín infused his painting with his own biases and narratives about the city, and its place — not just in the viceroyalty but in the world.

Together, the three painted scenes and the textual inscriptions suggest how processions, the performance of colonial authority, and painting were used for political purposes by administrators in the viceroyalty of Peru, especially to demonstrate their power in their dominions.)

Colonial Potosí and the desire to impress

Pérez de Holguín’s painting allows us to understand more about the population of this once-great city that at one point was the most important producer of Spanish wealth. It provides insight into how the city’s people interacted with those in power and the way that the city was connected to the rest of the viceroyalty.

Local legend states that the founding of Potosí begins with an Indigenous llama herder named Diego Huallpa who hid inside a crack in the mountain while he chased an escaped animal. When he was forced to spend the night inside the mountain, he lit a fire which allowed him to see a thick vein of silver running through the red mountain. The next day, he told the Spanish conquistadors what he had found, and the city surrounding the Cerro Rico started to grow as more and more Spaniards arrived to find their fortune.

Another local story says that the silver was actually discovered far earlier, by Huayna Capac, the eleventh Sapa Inka. The legend continues to say that when the Andeans began to extract the metal, a thunderous voice bellowed from the sky telling them that the silver was meant for other masters. From then on, the mountain was known as Potocchi, the local word for ‘thunder’, which later became hispanicized to Potosí. This story conveys the idea that the Spanish conquest of Peru was justified and predestined.

In the early colonial period, the population of the rough and arid Andean town boomed due to silver mining, as thousands of Spaniards arrived, along with thousands more free and forced Indigenous workers and enslaved Africans. The wealthiest potosinos had access to jewels and pearls imported from all over the world, as well as the finest silks and lace.

Potosinos watching the procession, and who have hung banners and paintings from balconies and on walls. Melchor Pérez de Holguín, Entry of Viceroy Archbishop Morcillo into Potosí (detail, 1716, oil on canvas, 240 x 570 cm (Museo de América, Madrid)

The excesses enjoyed by the people of Potosi as it boomed with silver mining was magnified by the cost and effort that was needed to import luxury goods into such a remote city so high in the mountains. After 1650, however, the population began to decline as the prices of silver dropped, and the costs of extracting the silver grew. Due to its remote location, it was particularly difficult to import necessary materials to continue extracting silver, and, by the time Pérez de Holguín painted Entry of Viceroy Morcillo in the 18th century, the town was considerably less powerful and wealthy than it had been a century prior.

Through the extravagant entrada with Morcillo, the people of Potosí hoped to secure the viceroy’s favor to revitalize the city and bring it back to its former glory. Even though the city was economically depressed by this time, Pérez de Holguín shows it as a splendorous jewel in the Spanish colonial crown. The citizens of Potosí watch the procession in their finest clothing. Paintings and expensive textiles decorate the city. The city is painted at its finest.

La Montaña Que Come Hombres (The Mountain the Eats Men)

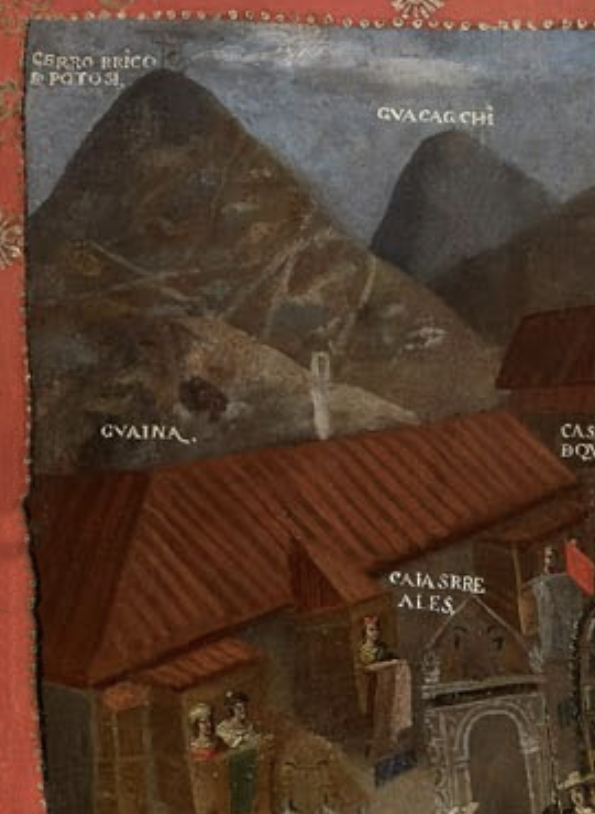

The Cerro Rico. Melchor Pérez de Holguín, Entry of Viceroy Archbishop Morcillo into Potosí (detail), 1716, oil on canvas, 240 x 570 cm (Museo de América, Madrid)

At the very top left corner of the painting, in the background of one of the smaller inset scenes Pérez de Holguín included the Cerro Rico, identifiable by the criss-crossing paths across the mountain’s face, and the label that Pérez de Holguín has included in the painting. It is very unusual that the artist has relegated the most iconic feature of the town to the edge of the painting.

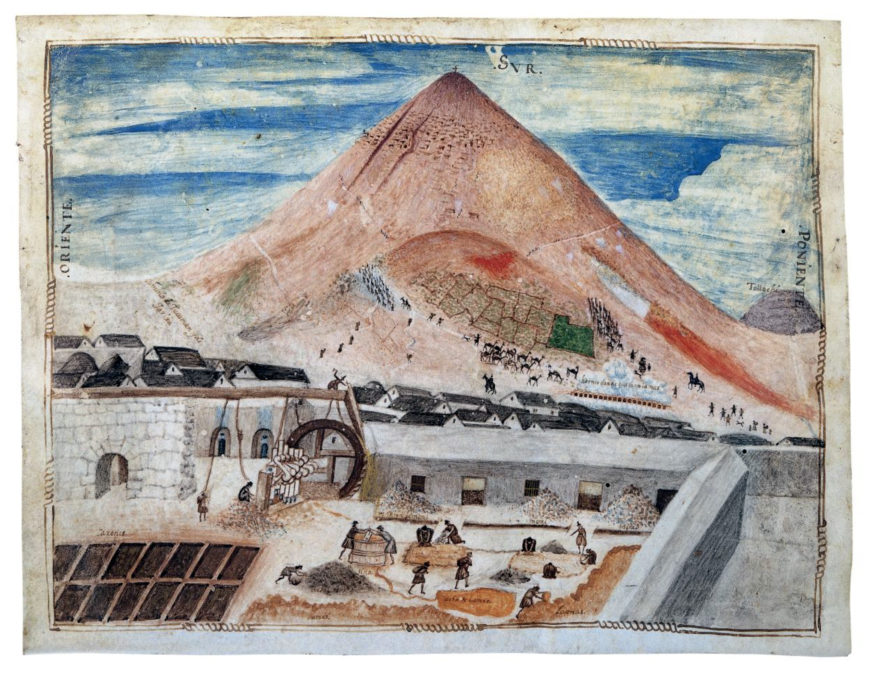

Most representations of Potosí privileged the mountain over the city, such as Pedro Cieza de Léon’s 1553 woodcut print of the city, or an anonymous watercolor drawing from the end of the sixteenth century, The Silver Mines of Potosí. Pérez de Holguín’s enormous and detailed painting emphasized life in the city rather than the mountain.

In creating this monument to civic pride, it is possible that the artist wanted to distance his city from the Cerro Rico, which, by the eighteenth century, had a notorious reputation for the brutal working conditions suffered by the Indigenous miners. The conditions were so deadly that the people of the city began to call the Cerro Rico “the mountain that eats men” (la montaña que come hombres). The poverty and destitution of most workers were excluded from Pérez de Holguín’s festive and extravagant scenes.

Melchor Perez de Holguin, Entry of Viceroy Archbishop Morcillo into Potosí, 1716, oil on canvas, 240 x 570 cm (Museo de América, Madrid)

A painted construction

Pérez de Holguín creates an opulent vision of the city of Potosí, recalling its history as a majestic metropolis, while disregarding the infamous stories of poverty and exploitation in the mines of the Cerro Rico. The great celebrations that he records, however, did not secure the financial and political help needed to return Potosí to its former glory. A few months following Morcillo’s entry into Potosí, he was replaced as viceroy and the city continued to suffer from increasing economic decline and no longer wielded the political and financial power that had—less than a century before—made it a gem in the Spanish colonial crown.