Signaling Spanish dominance in Cuzco, Peru

The transmission of Christianity to the Andes was both an ideological and artistic endeavor. Early missionaries needed to construct new spaces of worship and create images illustrating the tenets of the faith to recent converts.

The Convent of Santo Domingo in Cuzco (also spelled Cusco) offers an early glimpse into the evangelizing zeal of Peru’s mendicant orders’ project to create Christian structures atop the ruins of this recently conquered pre-Columbian city.

Remains of the Qorikancha, Inka masonry below Spanish colonial construction of the church and monastery of Santo Domingo, Cusco, Peru, c. 1440 (photo: Sarahh Scher, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The church was founded by the Dominican order in 1534 and built directly on the remains of the Coricancha (also spelled Qorikancha, meaning “golden enclosure”), Cuzco’s most important Inka (also spelled Inca) religious temple. The remains of the Inka temple form a curved foundation for the church. A small chapel rests on top of the curved wall at the back of the main church.

The placement of a Spanish Christian structure atop a decapitated Inka temple is a symbolic act of power and subjugation. The church serves as a material manifestation of the “triumph” of Christianity over paganism, hovering over the ruins of a conquered civilization. On the other hand, the Convent of Santo Domingo pays homage to both Spanish and Inka traditions. The church has an austere fortress-like façade with a three-arched entryway supported by Solomonic columns. Above that, the shuttered balcony is reminiscent of Hispano-Islamic (often termed mudéjar) architectural antecedents. Four of the original rooms of the Coricancha became incorporated into the cloister of the Church, giving both the exterior and interior a culturally mixed architectural signature. The finely cut masonry and trapezoidal windows of the original Inka structure became juxtaposed with the convent’s Baroque architectural flourishes modeled on European churches.

The Coricancha’s former function as an Inka religious temple dedicated to the sun does not necessarily disappear with the arrival of Christianity, but rather becomes intertwined with Christian notions of divinity. By choosing the most sacred site of the former empire as a site for conversion and worship, the Dominican missionaries recognized the transcendent power the Coricancha once held, and reoriented it toward a new dogmatic enterprise.

Solomonic columns on the facade of the church Santo Domingo, Cusco, Peru (image: AlemaPE-Tours)

12-sided stone, Inka stone masonry, Cuzco, Peru (image: Gvillemin, CC BY SA 3.0)

The sixteenth- and seventeenth-century chronicles of the conquest of Peru are rife with references to the unparalleled quality of Inka stonework; the Spaniards marveled at the ability of Inka stonemasons to produce mortarless structures whose stones were so closely aligned that one could not even fit a knife through their seams.

What at first sight may seem like an architectural incongruity, the interplay of Inka and Spanish stonework demonstrates the continued importance of Inka art forms in the colonial period as well as the intercultural exchanges that occurred in the making of colonial Cuzco.

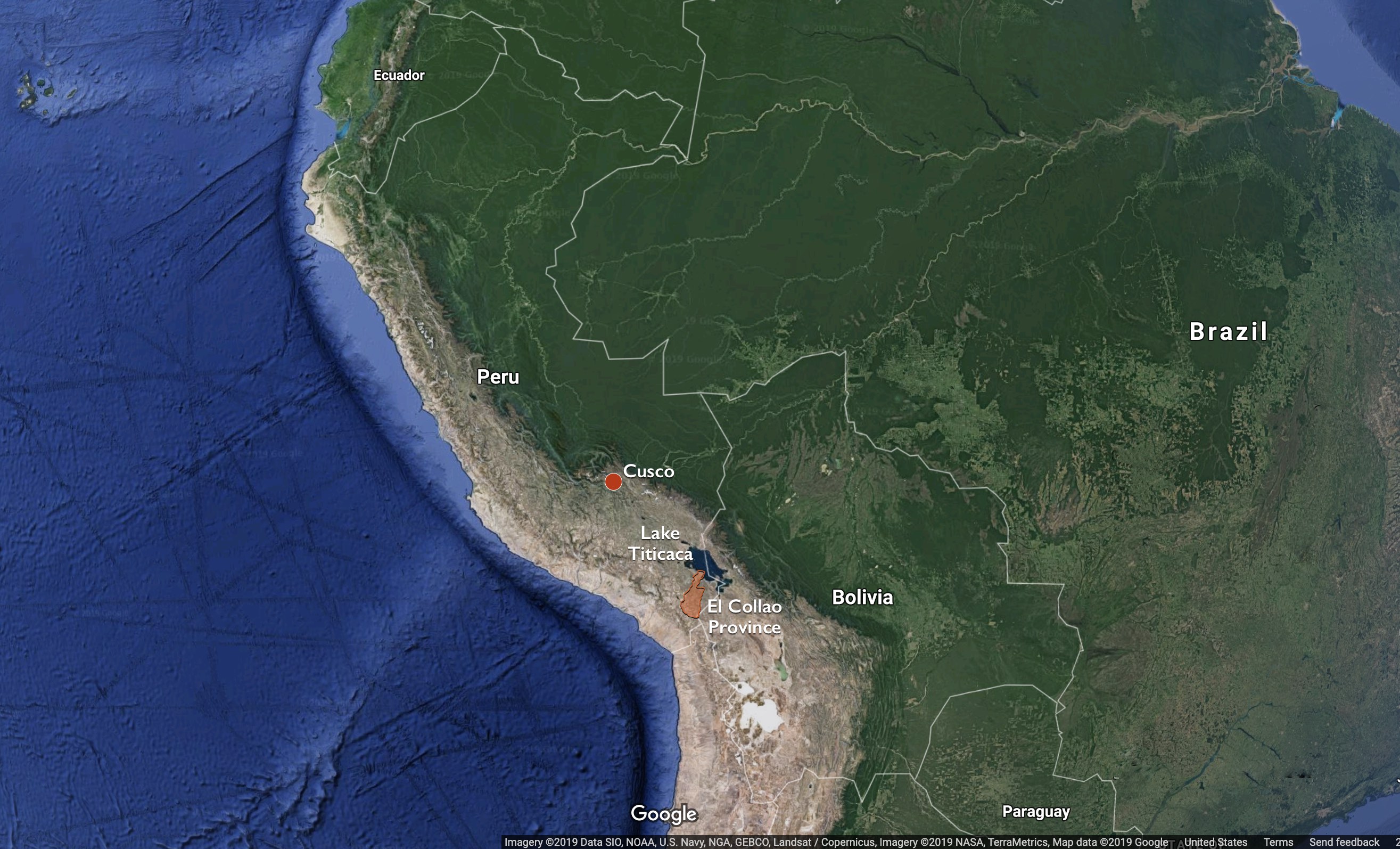

Missionary spaces in the Collao region

Portrait of Francisco Álvarez de Toledo, 16th century, oil on canvas (Museo Nacional de Arqueología, Antropología e Historia del Perú).

The missionary activities of the Dominican order extended far into southern Peru in the Lake Titicaca region. Clustered in this region of southern Peru, the missions of Juli, Pomata, and Chucuito share a number of similar features.

These mission churches formed a critical component of indigenous towns known as reducciones or pueblos de indios, which were instituted by the controversial Viceroy Francisco de Toledo during his appointment from 1569–1581. Reducciones were intended to isolate indigenous communities from their ancestral lands and shrines as a means of exerting political control and facilitating their conversion to Christianity.

The Church of La Asunción in the town of Chucuito, for example (in the Collao region of southern Peru) forms part of a large collection of Dominican mission complexes dedicated to the evangelization of native Andeans. The expansive adobe church emulates the large-scale mission churches of New Spain, also known as conventos. Like its colonial Mexican counterparts, the Church of La Asunción features a large atrium surrounded by a colonnade. The extensive outdoor space would have accommodated large congregations and also resonated with pre-Columbian Andean traditions of outdoor worship.

Facade, La Asunción, 1581-1608, Chucuito, Peru (image: Juan Pablo El Sous)

A restrained classicizing Renaissance-style carved stone façade frames the entry portal, flanked by pilasters and columns and topped with a pediment. Two carved niches on each side of the doorway may have originally contained sculptures of saints. The decorative relief carving along the arch and pediment provided an opportunity for Chucuito stonemasons to showcase their skills.

Early religious painting

Early painting of colonial Peru also served the didactic purpose of instructing indigenous people in the tenets of Catholicism through the language of images. European iconography traveled to the Andes through robust transatlantic trade networks that brought prints, pigments, paintings, brushes, and other art-related materials from Italy and Flanders by way of Seville, Spain.

European artists also traveled to South America to help meet the growing demand for religious images. One such artist was the Italian émigré Bernardo Bitti. Bitti, a member of the Jesuit order, trained in Rome, where he spent the early part of his artistic career. He subsequently spent time in Seville before arriving in Lima in 1575. He worked throughout the Viceroyalty of Peru, completing artistic commissions in Cuzco, Arequipa, La Paz, Potosí, and Chuquisaca.

One of his best-known paintings, entitled The Resurrection of Christ and dating to 1603, hangs in the Capilla San Ignacio in Arequipa’s La Compañía church. Christ’s serpentine, elongated figure pays homage to Italian Mannerist painters such as Jacopo Pontormo and Correggio.

A number of Bitti’s disciples emulated his characteristic muted color palette consisting of pastel pinks and blues and crisply folded drapery, extending Bitti’s artistic influence far into the seventeenth century. Bitti’s uncluttered compositions transmitted Biblical themes in a direct and engaging manner.

Additional resources

SAFE (Saving Antiquities for Everyone), Cultural heritage at risk: Peru

Introduction to Andean Cultures

The lofty ambitions of the Inca, National Geographic

The Inca road, Smithsonian Magazine