Portraiture functioned as an important artistic genre for wealthy elites to assert power and legitimacy in the Viceroyalty of Peru. From an art historical perspective, portraits also transmit a wealth of information about prevailing trends in clothing, jewelry, and other accessories with which the sitters are represented.

Portraits as visual documents

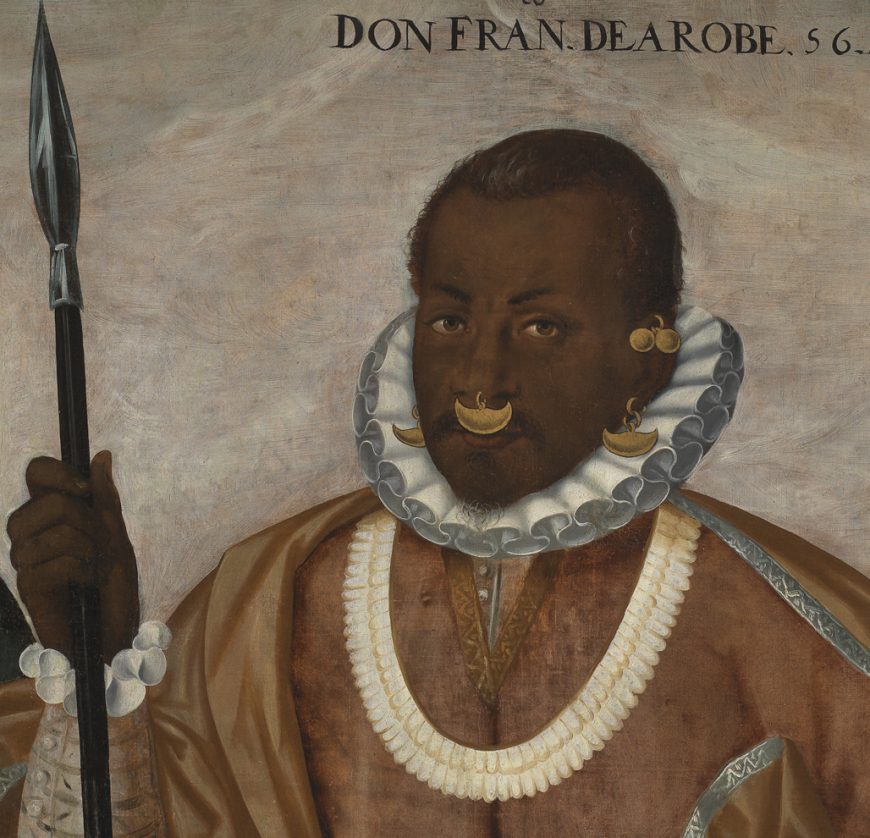

Andrés Sanchez Gallque, Three Mulatto Gentlemen of Esmeraldas, 1599, oil on canvas, 92 × 175 cm (Prado, Madrid)

Any discussion of colonial Andean portraiture must begin with Andrés Sanchez Gallque’s Three Mulatto Gentlemen of Esmeraldas from 1599, as it is the first signed and dated canvas in South America. The indigenous Quito artist depicts three men of indigenous and African descent. Don Francisco, at center, is flanked by his sons Don Pedro on his left and Don Domingo on his right.

All three of the men wear clothing associated with varying cultural affiliations. The stiff ruff collars and sleeves (called lechuguillos, or “little lettuces”) pay homage to Spanish and Flemish styles.

All three wear Andean uncus, or tunics, but the lustrous sheen of the fabrics suggests that they were fashioned from imported silk. Their necklaces derive from shells found along the coast of Ecuador, while the elaborate gold earrings and nose rings were likely fashioned out of gold extracted from mines in Colombia.

These men, in effect, embody a global material aesthetic made possible by the Spanish colonial enterprise. Taking up nearly the entirety of the picture plane, these men appear almost larger than life. Their open stance and steel-tipped spears further communicate a sense of power and authority.

A consideration of the historical context under which this portrait was produced, however, tells a different story. Don Francisco was the cacique (local indigenous ruler) of Esmeraldas, which had previously been an independent Afro-indigenous community on the north coast of Ecuador. In 1597, he submitted to Spanish authorities and the area became incorporated into the colonial bureaucracy. The judge responsible for this transfer of power, Juan de Berrio, commissioned this portrait as a gift to the Spanish King Philip III to commemorate his subjugation of the region. The portrait reveals the tensions of power at play in the realm of visual representation; Don Francisco and his sons assert the same kind of colonial authority to which they are also subjected. This image also demonstrates the power of portraits to act not only as depictions of an individual’s likeness, but as a visual “document” employed to commemorate political deeds.

Commemorative Portraits

Portraiture also became a tool for promoting alliances between members of the Spanish and indigenous elite. Marriage of Martín de Loyola with the Ñusta Beatriz and of Don Juan de Borja with Doña Lorenza Ñusta de Loyola, an anonymous canvas dating to c. 1680 that hangs in La Compañía Jesuit church in Cuzco, commemorates two marriages between Inka-descended women and prominent members of the Jesuit order.

Wedding of Martín de Loyola with the Ñusta Beatriz and of Don Juan de Borja with Doña Lorenza Ñusta de Loyola, c. 1680 (La Compañía Jesuit church, Cuzco)

The cartouche at the lower left, a common feature in colonial paintings, provides a biographical sketch of the figures depicted in the scene. The two central figures wearing black cloaks are St. Ignatius of Loyola, the founder of the Jesuit order, and St. Francis Borgia, who holds a human skull. On the left, Martín de Loyola, nephew of St. Ignatius, is shown marrying Beatriz Coya, a direct descendant of the Inka ruler Huayna Capac. To the right, Count Juan Enríquez de Borja y Almanza, grandson of St. Francis Borgia, marries the daughter of Martín de Loyola and Ñusta Beatriz.

The painting is not a realistic portrayal of reality, given the nearly forty-year gulf that separates the two marriages. Moreover, the former marriage occurred in Cuzco’s central plaza while the latter was performed in Madrid. Both locales are depicted in the respective backgrounds of the wedded couples. Instead, it is a commemorative portrait intended to demonstrate the seamless mixture of Spanish and Inka elite blood into perpetuity.

The power of history in the eighteenth century: Inka portraits

Effigies of the Inkas or Kings of Peru, c. 1725 (Convento de Nuestra Señora de Copacabana, Lima, Peru)

Portraits depicting the lineage of Inka and Spanish kings served as another means for solidifying links between the Inka and Spanish aristocracy. Effigies of the Inkas or Kings of Peru (c. 1725) depicts portraits of Inka kings from Sinchi Roca to Atahualpa, followed by portraits of Spanish monarchs from King Charles V to Ferdinand VI. At the top left and right are portraits of Manco Capac and Mama Huaco, the mythical founders of the Inka empire. Textual glosses identify and describe the deeds of each king. A portrait of Christ at the top center holding an olive branch, sword, and cross creates a compositional triangulation that places him at the apex of a hierarchy of rulership. Paradoxically, the Inka kings are positioned closest to Jesus rather than their Spanish successors.

The organization of the image creates a productive tension between two types of visual readings: viewing the image as composed of a tripartite spatial scheme with Christ and the Inkas occupying the “celestial” plane; or viewing it in conjunction with linear time, from left to right and top to bottom, implying a narrative of progress culminating in Spanish power.

Other aspects of the image show more definitive assertions of colonial power. The figure of the Inka king Atahualpa, located in the second-to-last cell in the middle row, looks directly at the Spanish King Charles V, pointing his lowered staff toward the Spanish king as a gesture of submission. Charles V points his finger to an illuminated cross, suspended in air to symbolize the entry of Catholicism to Peruvian lands. Atahualpa’s offering gesture served to normalize the conquest as a natural transfer of power.

These eighteenth-century lineage portraits attest to a renewed interest in the Inka past at a time when privileges granted to indigenous elites began to be curtailed under the Spanish Bourbon monarchy (1700–1808). Effigies of the Inkas or Kings of Peru asserts the primacy of the Spanish monarchy while also attesting to Inka cooperation in the creation of a Christian colony. Loyalty served as a crucial tool of political diplomacy in Spanish-Inka negotiations.

Elite criollo portraits

Pedro José Diaz (attr.), Portrait of Doña Mariana Belsunse y Salasar, c. 1780, oil on canvas, 198.4 x 127.2 cm (Brooklyn Museum)

Elite criollos (people born in the Americas, but of Spanish lineage) also commissioned large-scale portraits for display within private residences. Portrait of Doña Mariana Belsunse y Salasar (c. 1780), attributed to the artist Pedro José Diaz, depicts a wealthy member of Lima society who rose to local fame due to her involvement in a marital scandal. Belsunse y Salasar was unhappily married to an older man and decided to request a one-year grace period before consummating the marriage. She spent the subsequent year as a nun in a local convent where she stayed until he died. Upon his death, she resumed her life in Lima society and married one of his younger relatives, Agustín de Landaburru y Rivera.

Detail, Pedro José Diaz (attr.), Portrait of Doña Mariana Belsunse y Salasar, c. 1780, oil on canvas, 198.4 x 127.2 cm (Brooklyn Museum)

This portrait was painted after her return from the convent and displays a confident woman expressed through her three-quarter pose and direct eye contact with the viewer. Her finely detailed blue silk dress with lace sleeves reflects popular European fashions of the eighteenth century. The arched doorway looks out onto a tree-lined walkway with a fountain at the center, representing a park that she and her second husband donated to the city of Lima around 1755. This strategic inclusion in the portrait served as a means to highlight her social largesse and civic engagement. She delicately holds a fan in the right hand to connote modesty. The array of silver objects and jewelry in the portrait emphasize Belsunse y Salasar’s access to luxury goods, which she touches or wears as a means of embodying and even “performing” wealth. Unlike Effigies of the Inkas or Kings of Peru, which communicated power through recourse to history, Portrait of Doña Mariana Belsunse y Salasar remains firmly rooted in the present.

Identity and rebellion

Indeed, it was members of the criollo elite like Doña Mariana whose sights were fixed on the prospect of a future sovereign nation state — independent of Spain. At precisely the same moment when her portrait was painted in Lima, the southern Andean regions of Cuzco and La Paz were embroiled in bitter political conflict. The indigenous-led Tupac Katari Rebellion (1777–1780) in Alto Peru (present-day Bolivia) and Tupac Amaru Rebellion (1780–1783) sought to overthrow Spanish colonial rule and institute an indigenous power structure that drew inspiration from the Inka empire. The political conflict emerged largely as the result of increased economic burdens on indigenous peasant communities in the eighteenth century. These violent insurrections pitted natives against Spaniards, mestizos against criollos, and even native Andeans against each other, who were divided between Loyalist and Rebel factions.

The aftermath of the Tupac Amaru rebellion incurred around 100,000 deaths, the vast majority of whom were indigenous. These anticolonial rebellions exerted a cataclysmic impact on the colonial power structure, but they did not directly lead to independence. The movements for South American independence in the 1820s were largely dominated by criollos who resented their secondary status to peninsulares (Spaniards born on the Spanish peninsula) under the new Bourbon dynasty. The establishment of Latin American nations in the nineteenth century led to the development of new artistic genres, art academies, and arenas for the display of artworks. Nevertheless, colonial art left a longstanding legacy on the modern and contemporary arts of the Andes. Many of the portraits of South America’s liberators, for example, retain the same preference for flatness and poses found in eighteenth-century colonial portraits.

Additional resources:

Susan Verdi Webster, Lettered Artists and the Languages of Empire: Painters and the Profession in Early Colonial Quito (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2017)

Thomas Cummins, “Three Gentlemen from Esmeraldas: A Portrait Fit For a King,” in Slave Portraiture in the Atlantic World, ed. Agnes Lugo-Ortiz et al., 118-45. (Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press, 2013), 126-38.

Learn more about the Portrait of Doña Mariana Belsunse y Salasar