Sitter wearing the mascaypacha (detail), Portrait of Don Marcos Chiguan Topa, c. 1740–45, oil on canvas, 199 x 130 cm (Museo Inka, Cuzco)

A man stands proudly wearing fine clothing and holding a banner. He gazes piercingly at the viewer. At first glance, we notice that the work contains many of the trappings of European Baroque portraiture—a standing, elegantly dressed full-length figure, a red curtain in the background, and the solemn gravitas of the sitter’s gaze. Yet looking more closely at this portrait reveals that it originates not in Western Europe, but in the Andes of Peru. The man depicted is a wealthy and influential 18th-century curaca, or Andean Indigenous nobleman named Don Marcos Chiguan Topa.

This painting was most likely commissioned by Don Marcos himself as one in a series that traced his imperial lineage back to a legendary leader named Inka Lloque Yupanqui. [1] Don Marcos claimed to be descended from the first Inkas to convert to Christianity due to the missionizing efforts of the Spanish. This was a strategic move. Much as the painting visually connects Spanish and Inka cultural symbols, Don Marcos’ claims to both Inka and Spanish cultures served to position him within the highest levels of the colonial hierarchy. In this way, Inka nobles like Don Marcos retained power within their local communities and served as middlemen between the Spanish authorities and the local Andean Indigenous population.

Embodiment and representation in the colonial Andes

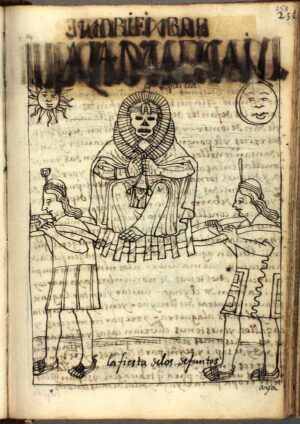

Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala, “Inka Mummy” in Nueva Corónica y Buen Gobierno, c. 1610 (Royal Danish Library, Copenhagen)

The Don Marcos portrait shows emblems of both Inka and Spanish elite status. While European portraits could be used to commemorate dead ancestors, the Inka had no need for these tools of representation because of their belief in kamay, meaning essence or life force. The kamay of an individual could be transferred from the physical body of a person into objects that became embodied with their essence. Deceased royals had their kamay preserved in two forms: one was the mummified body (called mallqui), and the second was through what was called the wawqi, or stone embodiment.

During the lifetime of the ruler, material from the physical body in the form of fingernail and eyelash clippings would be deposited into the crevices of a specially selected rock formation. This rock thereby obtained the kamay of that person, embodying what art historian Carolyn Dean describes as the masculine essence of the ruler. Upon their death, the body would be mummified, and came to embody the female aspect of the ruler. [2] These mummies would be ritually fed, consulted, and paraded through the streets at important times of pageantry. Within these Inka notions of embodiment, portrait traditions that focused on representations of the body were unnecessary. It was not until the colonial period that Inka elites began commissioning painted portraits, and the Don Marcos portrait is a key example of the way the portraits blended Spanish and Inka symbols.

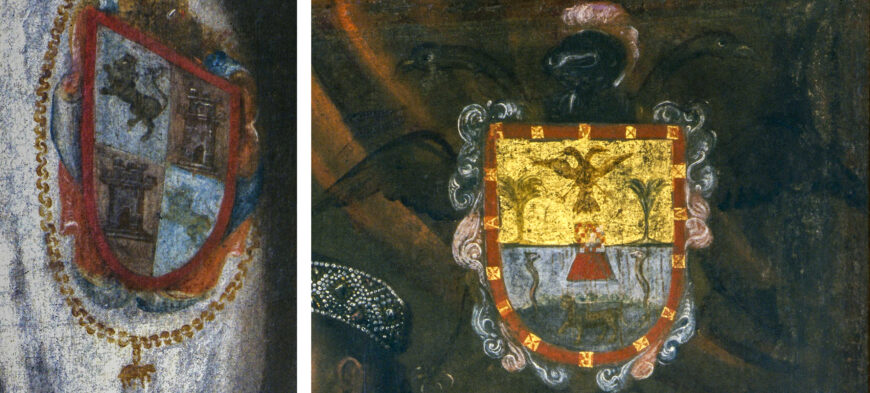

Coats of Arms (details), Portrait of Don Marcos Chiguan Topa, c. 1740–45, oil on canvas, 199 x 130 cm (Museo Inka, Cuzco)

Trappings of elite status

Let’s look closely at what the portrait is telling us. Notice the scarlet fringe on the figure’s forehead that is connected to an elaborate headdress. This regalia is called the mascaypacha in Quechua (the language of the Inka). In Pre-Hispanic times this crown was worn only by the Sapa Inka, or King of the Inka Empire. In the colonial period it came to be worn by a variety of Indigenous elites who claimed descent from the Inka royal family. Don Marcos holds a royal military standard in his right hand featuring the coat of arms of the Spanish kingdoms of Castile and Aragon. He therefore identifies himself as a standard bearer carrying the flag that would have been used in public processions such as during the famed Corpus Christi celebrations in Cuzco.

A prominent coat of arms is located at the top right of the painting featuring both Spanish and Inka emblems. The upper shield element features a bicephalic eagle (associated with the Spanish Habsburg monarchy) flanked by palm trees, while the lower shield element contains a tiger flanked by two snakes. Floating in the center is a red trapezoid, which seems to echo the shape and color of the sitter’s maskaypacha fringe. This elaborate coat of arms was granted by Spanish king Charles V in 1545 to an ancestor of Don Marcos’ named Paullu Topa Inka. [3] This ancestral emblem along with the lengthy inscription in the cartouche detailing his ancestry and titles draws attention to Don Marcos’ elite Inka genealogy. Within the Spanish Viceroyalty of Peru, Inka elites could maintain ancestral lands and status within their local communities.

Don Marcos fashions himself as an elite “Don,” or gentleman, wearing European-style clothing including elaborate lace and gilded flourishes. Around his neck, he wears an emblem of the Virgin Mary as a profession of his Christian faith. By picturing himself as a wealthy gentleman and a Christian, Don Marcos displays his loyalty to the Spanish crown while also maintaining ties to his Inka royal heritage. This mediation allowed for Indigenous elites like Don Marcos to maintain their elevated statuses while under Spanish rule—and he does so by employing conventions of portraiture seen on both sides of the Atlantic. The prominent inclusion of coats of arms and cartouches are primarily seen in Viceregal portraiture as ways of emphasizing the status and lineage of the sitter. Other trappings, however, point to Europe. We see this in the life-sized painting and in Don Marco’s full-bodied stance. His size is further emphasized in opposition to the dwarf attendant located behind him just above the white cartouche. This diminutive figure may not reference a real person, but may instead be a reference to dwarfs seen in Baroque portraits, though his attendant is rendered as an Indigenous person versus a European or African in European examples. Another typical Baroque convention is the use of the red curtain revealing Don Marcos, adding a theatrical flair to the composition.

By combining aspects of Inka material culture with Spanish methods of representation, the portrait speaks to the negotiations of the colonial period in Peru. While colonization was undoubtedly violent and fraught, the portrait of Don Marcos, like so many colonial artworks, shows the resistance and survival of Indigenous peoples who ingeniously adapted to their circumstances, thereby creating a new visual tradition.

Notes:

[1] Luís Eduardo Wuffarden, “Marcos Chiguan Topa,” The Colonial Andes: Tapestries and Silverwork, 1530–1830, edited by Elena Phipps, Johanna Hecht, and Cristina Esteras Martín (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2004), p. 200.

[2] Carolyn Dean, “The After-life of Inka Rulers: Andean Death Before and After Spanish Colonization,” Death & the Afterlife in the Early Modern Hispanic World, edited by John Beusterien and Constance Cortez (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2010), p. 32.

[3] Dana Leibsohn and Barbara E. Mundy, Vistas: Visual Culture in Spanish America, 1520–1820, 2015.

Additional resources

Learn more about the Global Baroque

Read about this work and Colonial Spanish America on Vistas

Visit the Museo Inka in Cuzco, Peru

Introduction to the Viceroyalty of Peru on Smarthistory

Elena Phipps, Johanna Hecht, and Cristina Esteras Martín, editors, The Colonial Andes: Tapestries and Silverwork, 1530–1830 (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2004).

Emily A. Engel, Pictured Politics: Visualizing Colonial History in South American Portrait Collections (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2020).