European-style paintings in colonial Lima

In the Peruvian city of Lima, a visitor will encounter a bustling modern city, the natural beauty of the coast, and numerous references to the city’s layered past, including the ruins of structures made by indigenous cultures, and churches built during the colonial period. Filling those churches are paintings and sculptures that call to mind a tradition not born in South America, but in western Europe — that of the Renaissance, with its illusionistic devices, technical virtuosity, and figural narratives. Some of these paintings (along with books and prints) were imported from Spain, Flanders, and Italy. Some were painted by émigré artists resident in Lima. But why were European artists making paintings in colonial Lima?

The Peruvian city of Lima, Peru (photo: Allan Grey, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Bernardo Bitti was one of many artists who made the journey across the Atlantic in this period as part of the Spanish Crown’s effort to colonize and evangelize the indigenous populations of what is today Mexico, Central America, and parts of South America. Bitti was a sixteenth-century artist from Camerino, Italy, in the Marches region, who produced paintings for churches throughout the Peruvian viceroyalty. He arrived in Lima, the viceroyalty’s capital, in 1575. Looking at Bitti’s work in Peru offers an opportunity to better understand the practice of evangelization. It also helps us to recognize that what we consider as Italian Renaissance art was not just a European phenomenon, but a global event.

An international Renaissance

The year 1492 is firmly planted in the western consciousness, as the fateful year that Christopher Columbus accidentally landed in Santo Domingo in what is now called the Dominican Republic. It also happens that this thing we call the Renaissance, an influential period of artistic and cultural achievement, took place contemporaneously, in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. What then happens when we begin to consider this period of art making in correspondence with the beginnings of international encounters? The resulting collisions of belief, history, and art allow us to consider the period as one that was not localized in places like Italy and Flanders, but was in fact international in its scope.

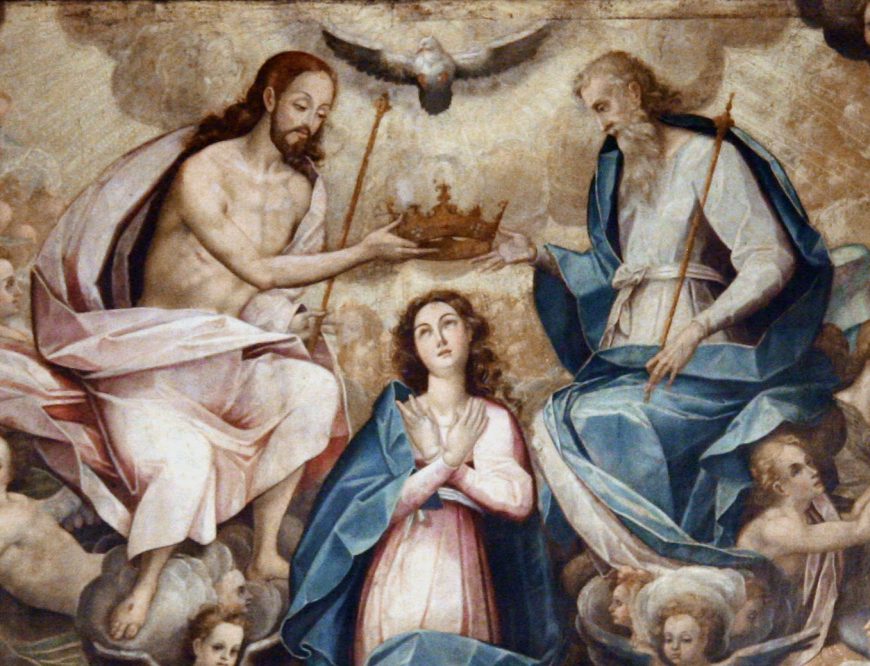

Bernardo Bitti, Coronation of the Virgin, 1575 – 80, Church of San Pedro, Lima, Peru, tempera (photo: Jonathan.adrianzen, CC BY-SA-4.0)

The Coronation of the Virgin

Bitti’s first project in Lima was a large altarpiece depicting the Coronation of the Virgin, for the Jesuit Church of San Pedro. The subject matter is fairly straightforward, an image of the Virgin Mary rising into the heavens, to be crowned by Christ to her right, God the Father to her left, and a dove representing the Holy Spirit overhead, while angels playing musical instruments gather in celebration.

![Diego Valadés, Rhetorica christiana : ad concionandi et orandi vsvm accommodata, vtrivsq[ue] facvltatis exemplis svo loco insertis, 1579](https://smarthistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/friar-preaching-870x1284.jpg)

Diego Valadés, Rhetorica christiana : ad concionandi et orandi vsvm accommodata, vtrivsq[ue] facvltatis exemplis svo loco insertis…, 1579 (Internet archive)

Church of San Pedro, completed 1638, Lima, Peru (photo: Manuel González Olaechea, CC BY-SA-3.0)

The context of the Counter Reformation

Bernardo Bitti was a painter, but also a Jesuit, who traveled to Lima as part of the order’s evangelization efforts. The Jesuits were at the forefront of global missionary efforts during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Issues and ideas from Europe intersected with the agenda of missionaries in Latin America. Throughout colonization, the Catholic Church remained embroiled in the Counter Reformation, a campaign to reinvigorate the Church and reform, where necessary, after suffering the criticisms of the Protestant Reformers in Northern Europe. Bitti’s Coronation of the Virgin did contribute important narrative information about Christian belief, but it also served as visual propaganda of the Catholic Church’s reform.

There are several elements to this painting that highlight Bitti’s attention to the Counter-Reformation agenda. Most important is the glorification of the Virgin Mary. The painting serves as a reminder of her divinity and an encouragement to worship her as queen of heaven. In this period, the Catholic Church re-asserted its dedication to the Cult of the Virgin, partly in response to criticisms from the Protestant Reformers. Between 1545 and 1563, the Council of Trent (a meeting of Church officials, convened to address the crisis of the Reformation, and among many other proclamations), affirmed the value of worshipping the saints, and the Virgin Mary. The Council also instructed that sacred art was a valid and appropriate undertaking.

Bitti’s painting would have served as a Counter-Reformation example of how art should serve its didactic and devotional functions. It is clear and legible. The composition is symmetrical, with the most important figures easy to locate, and their significance over the other figures made clear by the attention paid to them by surrounding angels. Additionally, the painting represents the Virgin’s crowning, not by just Christ, or God the Father, but by the Holy Trinity, the inclusion of the white dove completing this all important triad. Bitti’s inclusion of the Trinity as three separate entities was a critical iconographic choice. European commentators were careful to instruct artists of this period to be clear in their depictions of the Trinity, never as three identical figures, or one body with multiple faces, but as an older man, a younger man, and a dove. For Bitti, painting in Lima for a diverse audience of Europeans and newly converted indigenous viewers, the accurate depiction of the Trinity would have been of particular importance.

Detail showing the Holy Trinity in Bernardo Bitti’s Coronation of the Virgin (photo: Jonathan.adrianzen, CC BY-SA-4.0)

Representations of the Trinity were potentially problematic in the Andes, where the indigenous populations had for centuries followed polytheistic religions. Christian missionaries sought to stamp out any residue of such pagan beliefs and traditions. A painting presented by Christian clergy of three beings, representative of God, could be confusing for the local indigenous converts. These same missionaries vehemently prohibited the worship of multiple gods.

The matter was further complicated when Europeans learned that some Andean religions pictured their gods in threes. For example, three statues of the god representing the Sun stood in Cuzco; Apointi, Churiinti, Intiquaqui were the father Sun, the son Sun, and the brother Sun. Upon learning of this predisposition for a conception of a trinity in the local indigenous religions, the clergy attempted to use this potential complication to their advantage. They preached the idea that the pre-Christian existence of a trinity was merely a precursor for the true Trinity that the indigenous populations were now learning about. For them, the truth had been laying in wait, but obscured, for centuries. Images of the Trinity would become common in Spanish colonial art as tools to engage the locals with a familiar image but ones that needed to be appropriately presented according to Catholic doctrine.

View of the Coronation of the Virgin, Church of San Pedro, Lima, Peru (photo: Jonathan.adrianzen, CC BY-SA-4.0)

Bitti’s paintings were also tools implemented to aid in the imposition of western European culture onto the indigenous Andean people. Bitti’s figural, narrative, illusionistic style of representation was steeped in the traditions of Italian Renaissance aesthetics. It was informed by the concept of Leon Battista Alberti’s “painting as window,” which contrasted violently with the centuries old visual traditions of the Andes, where art tended to be more abstract, geometric, and not representational. So, while it was certainly important for Bitti to use his altarpiece to communicate Christian narrative appropriately, this painting was also a weapon used by the Europeans in their campaign to replace ancient Andean beliefs and culture with their own understanding of the world.