Inka ruins, Písac, Peru (photo: Chensiyuan, CC BY-SA 3.0)

The Andes mountains (image: NASA)

A land of contrasts

“The Andes” can refer to the mountain range that stretches along the west coast of South America, but is also used to refer to a broader geographic area that includes the coastal deserts to the west and into the tropical jungles to the east of those mountains. This region is seen as home to a distinct cultural area—dating from around the fourth millennium B.C.E. to the time of the Spanish conquest—and many of these cultures still persist today in various forms.

From the desert coast, the mountains rise up quickly, sometimes within 10-20 kilometers of the Pacific Ocean. Therefore, the people who lived in the Andes had to adapt to varying types of climate and ecosystems. This diverse environment gave rise to a range of architectural and artistic practices.

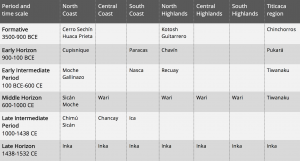

Table showing the time periods, cultures, and territories within Andean prehistory. While the table ends with the Spanish conquest of the Inka in 1532, native cultures continue in the Andes, with many changes from their pre-conquest forms.

Deserts, mountains, and farms

Though much of the Andean coast is near the Equator, its waters are cold, due to currents from the Antarctic. This cold water is rich in sea life; however, during El Niño years, warm water takes over, leading to large die-offs of fish and marine mammals, and often creating catastrophic flooding on the coast.

Ocean and cliffs near the site of Pacatnamú, Peru, with the foothills of the Andes visible in the distance (photo: Dr. Sarahh Scher)

In normal years, the coast is very dry. The rivers that run to the coast, fed by melting snow from the Andes mountains (called the Cordillera Blanca, or White Mountains, in contrast to the Cordillera Negra, or Black Mountains to the west where snow does not fall), create areas of agricultural lands interspersed with desert. Cultures eventually learned to create canals, allowing them to irrigate more land, and irrigation remains important to farming on Peru’s coast.

As the elevation climbs, different ecological zones are created, and people of the Andes used these to grow different products: maize (corn), hot peppers, potatoes, and coca all grew at different elevations. Some cultures (such as the Cupisnique and Paracas) developed on the coast, and incorporated seafood into their diet. They would trade with the cultures that lived in the highlands (such as the Recuay and the inhabitants of Chavín de Huantar) for the things they could not grow for themselves. The people in the highlands would likewise trade with the coastal peoples for dried fish and products that would not grow at their elevation, as well as exotic animals like parrots from the tropical jungles to the east.

Plants and animals

Leaves of an Erythroxylum coca plant, Colombia (photo: Darina, CC BY-SA 3.0)

The plants and animals of the Andes provided ancient peoples with food, medicine, clothing, heat, and many other resources for daily life. As noted above, the rapid change in elevation of the Andes meant that many different foods could be grown in a compressed area. Celery was a staple food of the highlands, and maize and manioc were important in the lower elevations.

Coca grew in the highlands but was traded all over the Andes. The leaves of this plant, when chewed, provide a stimulant that allows people to walk for long periods at high altitude without getting tired, and it suppresses hunger. It was used by travelers in the highlands, but was also used in ritual practices to endure long nights of dancing. In modern times, people drink it as a tea to help with the symptoms of altitude sickness.

Terraced hillsides at the Inka ruins of Písac, Peru (photo: Paulo JC Nogueira, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Farming in the steep topography of the mountains could be difficult, and an important innovation developed by the Andeans was the use of terracing. By creating terraces (essentially giant steps along the contours of a mountain) people were able to make flat, easily worked plots. The terraces were formed by creating retaining walls that were then backfilled with a thick layer of loose stones to aid drainage, and topped with soil.

The most important animals in the highlands were camelids: the wild vicuña and guanaco, and their domesticated relatives, the llama and alpaca. Alpacas have soft wool and were sheared to make textiles, and llamas can carry burdens over the difficult terrain of the mountains (an adult male llama can carry up to 100 pounds, but could not carry an adult human).

Left: Alpacas, Ecuador (photo: Philippe Lavoie, public domain); Right: Llama near Cusco, Peru (photo: Dr. Sarahh Scher)

Both animals were also used for their meat, and their dried dung served as fuel in the high altitudes, where there was no wood to burn. Andean camelids, like their African and Asian cousins, can be very headstrong. If they are overloaded, they will sit on the ground and refuse to budge. Because of this, the ancient people of the Andes did not have domesticated animals that could carry them or pull heavy wagons, and so roads and methods of moving people and goods developed differently than in Europe, Asia, and Africa. The wheel was known, but not used for transport, because it simply would not have been useful.

Textile arts

Weaving with traditionally dyed alpaca wool, Chinchero, Peru (photo: Rosalee Yagihara, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

The ancient peoples of the Andes developed textile technology before ceramics or metallurgy. Textile fragments found at Guitarrero Cave date from c. 5780 B.C.E. Over the course of millennia, techniques developed from simple twining to complex woven fabrics. By the first millennium C.E., Andean weavers had developed and mastered every major technique, including double-faced cloth and lace-like open weaves.

Andean textiles were first made using fibers from reeds, but quickly moved to yarn made from cotton and camelid fibers. Cotton grows on the coast, and was cultivated by ancient Andeans in several colors, including white, several shades of brown, and a soft grayish blue. In the highlands, the alpaca provided soft, strong wool in natural colors of white, brown, and black. Both cotton and wool were also dyed to create more colors: red from cochineal, blue from indigo, and other colors from plants that grew at various elevations. Alpaca wool is much easier to dye than cotton, and so it was usually preferred for coloring. The extra time and effort needed to dye fibers made the bright colors a symbol of status and wealth throughout Andean history.

Ceramics

Oxygenated sculptural ceramic ceremonial vessel that represents a dog, c. 100-800 C.E., Moche, Peru, 180 mm high (Museo Larco).

Though ceramics were not as valuable as textiles to Andean peoples, they were important for spreading religious ideas and showing status. People used plain everyday wares for cooking and storing foods. Elites often used finely made ceramic vessels for eating and drinking, and vessels decorated with images of gods or spiritually important creatures were kept as status symbols, or given as gifts to people of lesser status to cement their social obligations to those above them.

There are a wide variety of Andean ceramic styles, but there are some basic elements that can be found throughout the region’s history. Wares were mostly fired in an oxygenating atmosphere, resulting in ceramics that often had a red cast from the clay’s iron content. Some cultures, such as the Sicán and Chimú, instead used kilns that deprived the clay of oxygen as it fired, resulting in a surface ranging from brown to black.

Non-oxygenated ceramic feline bottle, 12th–15th century, Chimú (Peru), 28.26 cm high (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Decoration of ceramics could be done by incising lines into the surface, creating textures by rocking seashells over the damp clay, or by painting the surface.

Some early elite ceramics were decorated after firing with a paint made from plant resin and mineral pigments. This produced a wide variety of bright colors, but the resin could not withstand being heated and so these resin-painted wares were only for display and ritual use. Most ceramics in the Andes instead were slip-painted. Slip is a liquid that is made of clay, and the color of the slip is determined by the color of the clay and its mineral content. Most slip painting was applied before firing, after the semi-dry clay had been burnished with a smooth stone to prepare the surface. The range of slip colors could vary from two (seen in Moche ceramics) to seven or more (seen in Nasca ceramics). Once fired, the burnished surface would be shiny. Ceramics, because of their durability, are one of the greatest resources for understanding ancient Andean cultures.

Female figurine, 1400–1533, Inka, Silver-gold alloy, 14.9 x 3.5 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Knife (tumi) with Removable Figural Handle, Moche, 50-800 C.E., green copper with patina, 11.43 x 2.5 x 1.43 cm (Walters Art Museum)

Metalwork

Metalworking developed later in Andean history, with the oldest known gold artifact dating to 2100 B.C.E., and evidence of copper smelting from around 900–700 B.C.E. Gold was used for jewelry and other forms of ornamentation, as well as for making sculptural pieces. Inka figurines of silver and gold depicting humans and llamas have been recovered from high-altitude archaeological sites in Peru and Chile. Copper and bronze were also used to create jewelry and items like ceremonial knives (called tumis).

Architecture

The architecture of the Andes can be divided roughly between highland and coastal traditions. Coastal cultures tended to build using adobe, while highland cultures depended more on stone. However, the lowland site of Caral, which is currently the oldest complex site known in the Andes, was built mainly using stone.

Caral, Peru, founded c. 2800 B.C.E. (photo: Pativilcano, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Beginning with Caral in 2800 B.C.E, various cultures constructed monumental structures such as platforms, temples, and walled compounds. These structures were the focus of political and/or religious power, like the site of Chavín de Huantár in the highlands or the Huacas de Moche on the coast. Many of these structures have been heavily damaged by time, but some reliefs and murals used to decorate them survive.

Painted adobe relief, Huaca de La Luna,100 CE to 800 C.E., Moche (Peru) (photo: Marco Silva Navarrete, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

The best-known architecture in the Andes is that of the Inka. The Inka used stone for all of their important structures, and developed a technique that helped protect the structures from earthquakes. Because of its stone construction, Inka architecture has survived more easily than the adobe architecture of the coast. Ongoing efforts by archaeologists and the Peruvian Ministry of Culture are also focused on restoring and preserving the great works of coastal architecture.

Inka stone doorways, Qoricancha, Cusco (photo: Jean Robert Thibault, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Ancient past, continuing traditions

From textiles to ceramics, metalwork, and architecture, Andean cultures produced art and architecture that responded to their natural environment and reflected their beliefs and social structures. We can learn much about these ancient traditions through the artifacts and sites that survive, as well as the many ways that these practices—such as weaving—persist today.

Additional resources:

Dualism in Andean Art from The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Timeline of Art History

Chavin (UNESCO World Heritage Site)

Project page for the Huaca de la Luna restoration by the World Monuments Fund