San Pedro Apóstol de Andahuaylillas, Peru, 16th century (photo: Bex Walton, CC BY 2.0)

The Sistine Chapel of the Americas

The Church of San Pedro de Andahuaylillas located outside of Cuzco contains an expressive decorative program that has earned it the title of the “Sistine Chapel of the Americas.” Filled with canvas paintings, statues, and an extensive mural program, the level of artistry and extravagance afforded to this church certainly rivals its counterparts in Renaissance Italy.

Nave looking toward the mural depicting The Paths to Heaven and Hell, San Pedro Apóstol de Andahuaylillas, Peru (photo: courtesy World Monuments Fund)

One of the church’s most well-known images is the mural painted on the interior entrance wall depicting an allegory of good and bad faith.

Luis de Riaño and indigenous collaborators, The Paths to Heaven and Hell, c. 1626, San Pedro Apóstol de Andahuaylillas, Peru (photo: courtesy World Monuments Fund)

The subject matter

Painted by the criollo artist Luis de Riaño and indigenous assistants, The Paths to Heaven and Hell transmits an important message to parishioners as they exit the church of the moral decisions they will confront on their spiritual journey. The two paths refer directly to a biblical passage which states,

Enter through the narrow gate. For wide is the gate and broad is the road that leads to destruction, and many enter through it / But small is the gate and narrow the road that leads to life, and only a few find it.Matthew 7:13–14

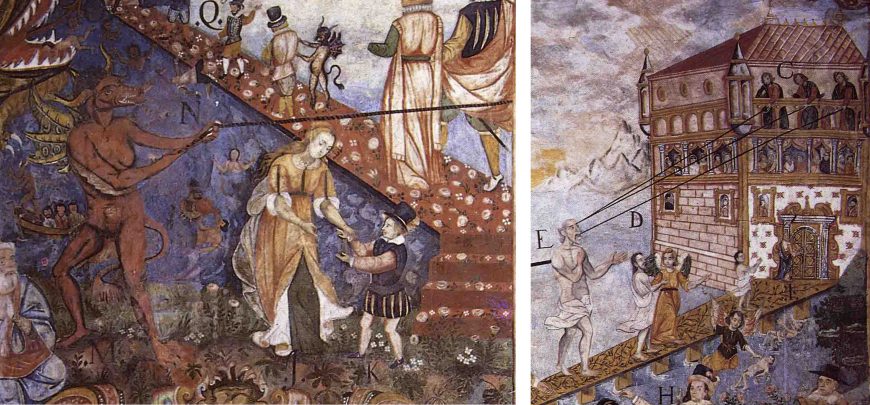

Luis de Riaño and indigenous collaborators, The Paths to Heaven and Hell. RIght: detail of the Devil holding a rope, and an allegorical female figure guiding a young man; right: the soul on the righteous path to the heavenly Jerusalem, c. 1626 (San Pedro Apóstol de Andahuaylillas, Peru)

A nude figure wearing nothing but a white sheet around his waist walks cautiously down the narrow and thorny path to the Heavenly Jerusalem, with three lines emanating from his head that lead to a representation of the Holy Trinity as three identical male figures. A thick rope also connects his back to the composition on the left of the doorway, where the Devil attempts to pull him over to the left side.

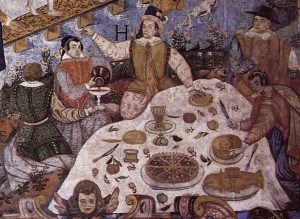

Luis de Riaño and indigenous collaborators, The Paths to Heaven and Hell, detail of the feast, c. 1626 (San Pedro Apóstol de Andahuaylillas, Peru)

Luis de Riaño and indigenous collaborators, The Paths to Heaven and Hell, detail of the Hell mouth, c. 1626 (San Pedro Apóstol de Andahuaylillas, Peru)

At the foreground of the scene is a banquet attended by four individuals feasting on wine, fish, bread, pie, and fruits. A mouth of Hell rears its head to the left of the path to Hell, its mouth agape with a naked sinner falling into his maw.

At the forefront of the scene is an allegorical female figure guiding a young man standing directly below the rope held by the devil. The path culminates at a castle engulfed in flames guarded by deer poised on the roof with bows and arrows.

The paths to Heaven and Hell were familiar tropes in medieval Christianity, with frequent representations in paintings, manuscript illuminations, and stage sets. Despite its decline in popularity in Europe by the Renaissance, this type of allegorical imagery carried great import in the colonial Andes.

The didactic iconography, painstakingly labeled with relevant biblical passages, was ideal for preaching Catholic doctrine to Andean parishioners. In fact, it is highly likely that Juan Pérez Bocanegra, the parish priest who commissioned the murals and accompanying decorative program, would have conducted his sermons using the murals as a focal point.

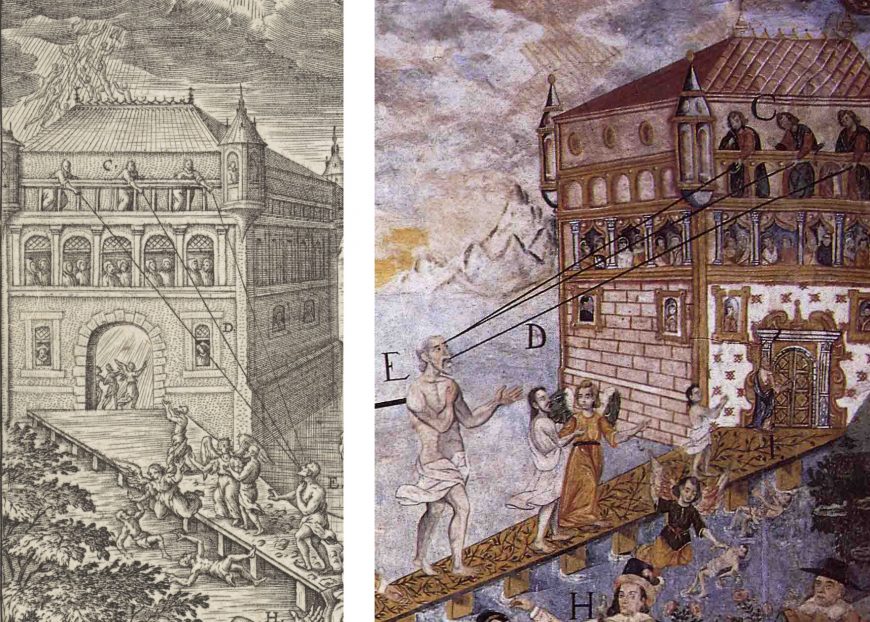

A New Jerusalem in the Andes

The mural is based on a print by Hieronymus Wierix entitled The Narrow and Wide Path, which Riaño copies relatively faithfully. One significant modification, however, can be found in the depiction of the path to Heaven. In the mural version, Riaño has added an additional figure at the doorway to the Heavenly Jerusalem holding a key. This individual likely represents Saint Peter the Apostle, the patron saint of Andahuaylillas. As the universal head of the church, Saint Peter held the keys to the kingdom of Heaven. Parishioners were thus given the implicit message that the church of their very community constituted a New Jerusalem on Andean soil. Indeed, the act of entering and exiting the church left congregations with a palpable reminder of the spiritual pilgrimage necessary for attaining salvation—and one that could be understood within the immediate parameters of their existence rather than as a place only to be visualized and imagined.

Left: Hieronymus Wierix, The Narrow and Wide Path, detail of the Heavenly Jerusalem, c. 1600; right: Luis de Riaño and indigenous collaborators, The Paths to Heaven and Hell, detail of the Heavenly Jerusalem, c. 1626 (San Pedro Apóstol de Andahuaylillas, Peru)

The path to Hell also contains an intriguing detail that is only visible upon close inspection of the mural. Three barely visible figures are seated in a devil-driven canoe beneath the mouth of Hell. The central figure wears an Inka-style tunic with a checkerboard pattern around the collar. Such regalia would have been worn by curacas, or local indigenous leaders. Another nearby indigenous figure ingests liquid from an Inka-style aryballos vessel called an urpu, probably filled with chicha. The figures differ dramatically from the rest of the mural in both content and style. They are painted using rougher strokes, indicating the hand of an assistant to Riaño. Moreover, the cultural specificity of the figures, linking them directly to the Inka past through objects and regalia, suggest that the assistant was of indigenous background.

Luis de Riaño and indigenous collaborators, The Paths to Heaven and Hell, detail of indigenous figures behind the Devil, c. 1626 (San Pedro Apóstol de Andahuaylillas, Peru)

Despite the obvious visual conflation of Andean ritual practices in association with the Christian concept of Hell, these figures were granted visibility in a religious arena that sought to eradicate Andean ancestral cultures. The Paths to Heaven and Hell infuses Christian iconography with local referents to facilitate a more personalized and culturally meaningful point of access for the seventeenth-century parishioners of Andahuaylillas.