Master of Calamarca, Archangel with Gun, Asiel Timor Dei, before 1728, oil on canvas and gilding, 160 x 110 cm (Museo Nacional de Arte, La Paz, Bolivia)

Guns, angels and fashion—three unexpected elements that co-exist in the Master of Calamarca’s painting Archangel with Gun, Asiel Timor Dei. Depictions of androgynous, stunningly attired, harquebus (a type of gun) carrying angels were produced from the late seventeenth century through the nineteenth century in the viceroyalty of Peru (a Spanish colonial administrative region which incorporated most of South America, and was governed from the capital of Lima, c. 1534–1820). First appearing in Peru these images were widespread throughout the Andes, in places such as La Paz, Bolivia, and as far as present-day Argentina. Representing celestial, aristocratic, and military beings all at once, these angels were created after the first missionizing period, as Christian missionary orders persistently sought to terminate the practice of pre-Hispanic religions and enforce Catholicism.

Master of Calamarca (detail), Archangel with Gun, Asiel Timor Dei, before 1728, oil on canvas and gilding, 160 x 110 cm (Museo Nacional de Arte, La Paz, Bolivia)

The harquebus is a firearm with a long barrel created by the Spanish in the mid-fifteenth century. It was the first gun to rest on the shoulder when being fired and was at the forefront of military weapon technology at the time. During the early eighteenth century, the Bolivian painter, the Master of Calamarca—identified as José López de los Ríos—or his workshop created a well known series of paintings depicting angels with harquebuses, which included Archangel with Gun, Asiel Timor Dei. The Latin inscription of Archangel with Gun, Asiel Timor Dei indicates the name of the angel, Asiel, and a particular quality: Fears God. This painting was found by itself, but was likely part of a larger series that included angels performing other activities such as drumming and holding lances.

Celestial beings

The Catholic Counter Reformation held a militaristic ideology that portrayed the Church as an army and angels as its soldiers. The armed angel in Asiel Timor Dei represented this philosophy: its gun and mere existence protects faithful Christians. Although the Council of Trent (1545–1563) had condemned all angelic depictions and names but those of Michael, Gabriel, and Raphael in the mid-sixteenth century, this ban was observed neither in the Viceroyalty of Peru nor in Baroque Spain. In fact, angels appeared in paintings in the royal convents of Las Descalzas Reales and Encarnación in Madrid, Spain. Some of the angels in the paintings of both these convents (painted by Bartolomé Román in the early seventeenth century) were reproduced and sent to the Jesuit Church of San Pedro in Lima, Peru. The workshop of the famed Spanish artist Francisco de Zurbarán also sent paintings of angels to the Monastery of Concepción in Lima. The Spanish Inquisition later prohibited the cult of angels in the mid-seventeenth century, but depictions of angels still flourished in the “New World.”

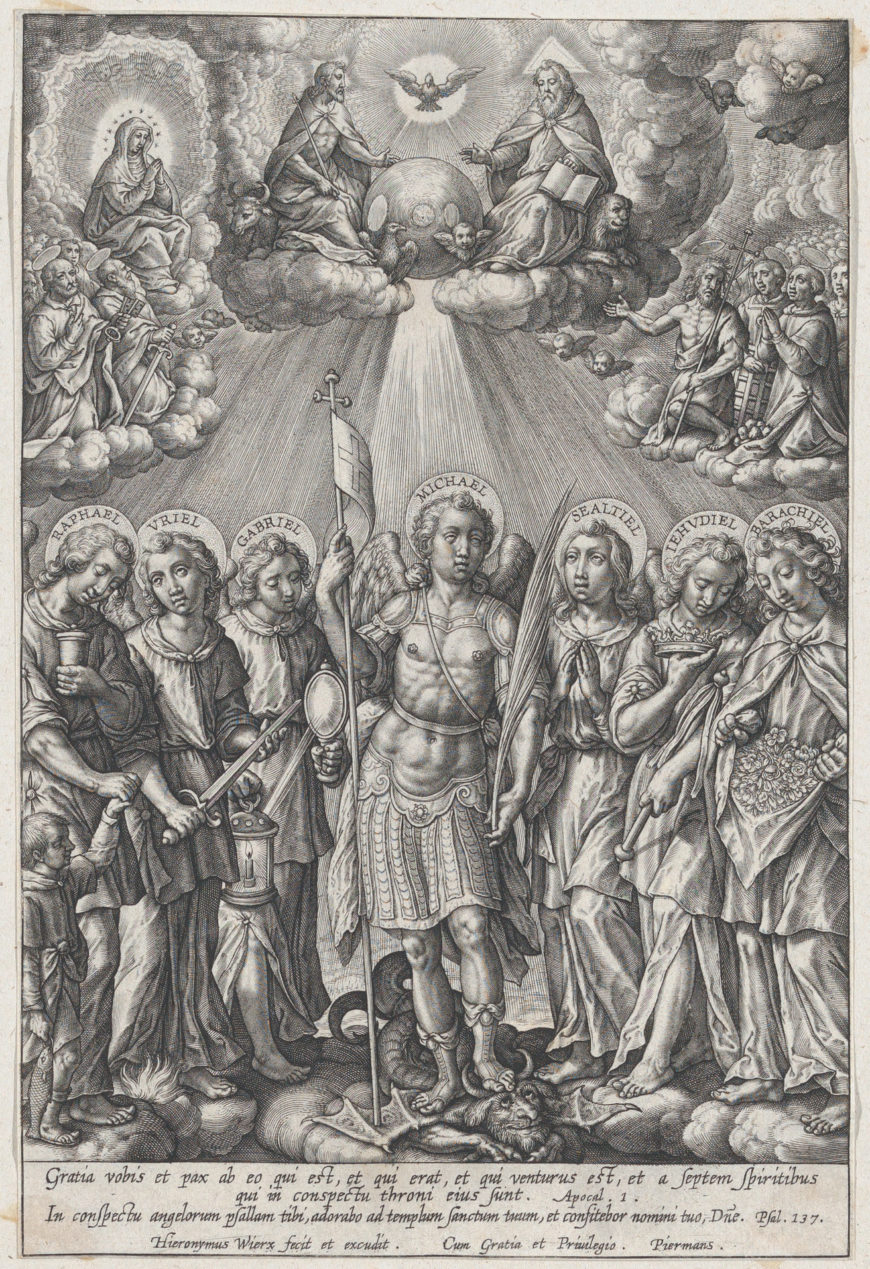

Hieronymus (Jerome) Wierix, St. Michael and Archangels (The Seven Archangels), 1570–1619, engraving, 15.9 x 10.5 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Prints by Flemish engraver Jerome Wierix depicting the seven archangels—Michael, Gabriel, Raphael, Uriel, Jehudiel, Barachiel, Sealtiel, all of whom appear in the Book of Enoch—may have circulated throughout the Andes in the seventeenth century, and influenced angelology discourse in the Americas. European prints were widespread in the Americas because they were cost effective and circulated easily. However, the attire, name, and pose of angels such as the one in Asiel Timor Dei separate such angelic depictions from European prints, making it specifically American.

In Catholic teachings, angels explained the spiritual function of the cosmos, and thus could easily stand in for sacred indigenous beings. The asexual body of the angel in Asiel Timor Dei is consistent with biblical descriptions. Conversely, early American images often alluded to angels’ connection to certain indigenous sacred planets and natural phenomena, such as rain, hail, stars and comets.

The Aymara and Quechua peoples in the Andes may have associated the harquebus-bearing angel with Illapa, the Andean deity associated with thunder. Catholic angels were also equated with Inka tradition through the myth of the creator god Viracocha and his invisible servants, the beautiful warriors known as huamincas. The Latin inscriptions in the upper left corner of the painting Asiel Timor Dei are approximates of the original names of angels, and were related to the names of planetary and elemental angels in indigenous religions.

Military beings

Jacob de Gheyn, A soldier taking aim, from the Marksmen series, plate 11, The Exercise of Arms, 1608 (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Firearms did not exist in the Americas before the Spanish conquests, and there is evidence suggesting indigenous people saw guns as supernatural manifestations. Paintings of angels with guns were perhaps representative of both the power of the Spaniards over indigenous people and protection offered to faithful Christians. Prints from the 1607 series, The Exercise of Arms, by the Dutch Mannerist engraver Jacob de Gheyn, may have inspired paintings such as Asiel Timor Dei. These prints were models for specific military positions and demonstrated how to fire a gun. However, the Andean paintings differ from the prints, since they combine local dress and do not present realistic military positions. The angel in Asiel Timor Dei holds the gun like a professional, close to his chest. Although the gun is ready for firing, the angel does not hold the trigger, nor does he hold it at eye level. Contrary to the aggressive face of Gheyn’s soldier, the face of the angel is serene. The figure is graceful and almost looks like a dancer. The extended lines of the angel’s body recall the Mannerist style still preferred in the Americas in the seventeenth century (Mannerism was a style that came after the Renaissance, in the early 1500s).

Aristocratic beings

The dress of the angels with guns corresponds to the dress of Andean aristocrats and Inka royalty, and is distinct from the military attire of Gheyn’s harquebusiers. The dress of Asiel Timor Dei was an Andean invention that combines contemporary European fashion and the typical dress of indigenous noblemen. While colonial gentlemen were aware of fashion trends in Europe through the dissemination of prints, they invented certain outfits that came from Spanish America, such as the overcoat with large balloon-like sleeves. The excess of textile in Asiel Timor Dei indicates the high social status of its wearer. The elongated plumed hat is a symbol of Inka nobility, as feathers were reserved for nobles and religious ceremonies in pre-Hispanic society. The broad-brim hat on which the feathers are planted was in style in France and Holland around 1630.

Master of Calamarca (detail), Archangel with Gun, Asiel Timor Dei, before 1728, oil on canvas and gilding, 160 x 110 cm (Museo Nacional de Arte, La Paz, Bolivia)

During the first half of the eighteenth century, when Asiel Timor Dei was painted, the use of gold and silver became prohibited in the clothing of nobility. The military was, however, exempt from this rule. The angels with guns personify at once the military, aristocracy, and sacred beings, and were adorned with the most lavish attire. Francisco de Ávila, a priest in Peru who studied native customs, described the second coming of Christ as an event during which an army of well-attired angels with feathered hats would descend from the heavens. Ávila’s writings directly allude to the angels with guns, and to the late Viceregal belief that portrayed the first conquistadores as messengers from God.