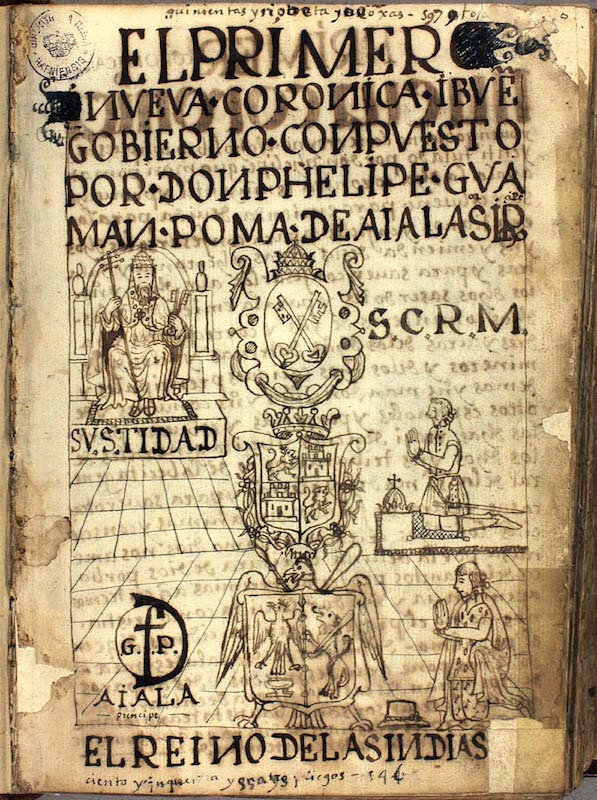

The author kneeling alongside the king of Spain before the Pope. Title page from Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala, The First New Chronicle and Good Government (or El primer nueva corónica y buen gobierno, c. 1615 (image from The Royal Danish Library, Copenhagen)

A very long letter

If you love to write letters, imagine writing one that is almost 1200 pages—complete with 398 full-page illustrations. Sound ambitious? Well, in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth century, the indigenous Andean man, don Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala, actually wrote such an extensive letter in pen and ink addressed to the Spanish king (at one point Philip II, and then Philip III). It was called The First New Chronicle and Good Government (or El primer nueva corónica y buen gobierno, c. 1615). Guaman Poma wrote about Andean peoples prior to the arrival of Europeans in the 1530s as well as documented the current colonial situation (“Andean” refers to the Andes mountains, in what is today Peru). He was keen to record the abuses the indigenous peoples suffered under the colonial government, and hoped that the Spanish king would end them. Guaman Poma hoped to have New Chronicle printed when it arrived in Europe, and for this reason he borrowed from type-setting conventions when writing the textual inscriptions accompanying his illustrations, such as those on the frontispiece to his letter (above). It also explains why he left his images in black-and-white.

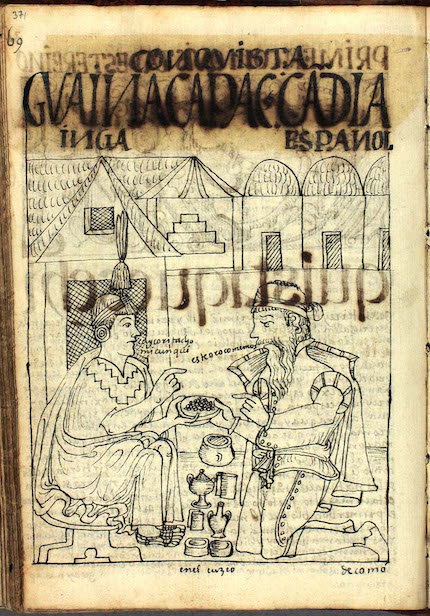

“The Inka asks what the Spaniard eats. The Spaniard replies: ‘Gold,'” from Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala, The First New Chronicle and Good Government (or El primer nueva corónica y buen gobierno), c. 1615, p. 371 (image from The Royal Danish Library, Copenhagen)

While the first part of the manuscript addresses Andean life and culture prior to the invasion of the Spaniards, the second half focuses on viceregal life and administration (viceregal refers to the administrator who ruled the Spanish colony in the name of the king from the Conquest of 1534 until independence from Spain in 1820). For the viceregal section of the letter, Guaman Poma discusses topics as broad as parish priests and local native administrators to religious and moral considerations and viceregal towns and cities. So New Chronicle is not only ambitious in length, but also in scope!

Significance

This amazing letter is special for several other reasons. First, it is the most famous manuscript from South America dated to this time period in part because it is so comprehensive and long, but also because of its many illustrations. Few illustrated manuscripts survive from this time period, and Guaman Poma’s has no rival. Second, it is important for what it tells us about pre-Hispanic Andean peoples, especially the Inka. While the Inka had an advanced recording system that used knots on cords, called khipus, researchers have not yet been able to translate them. Guaman Poma’s discussion of Inka culture provides us with information that would otherwise be lost to us, even if we have to be aware that he wrote this information a generation after the Spaniards defeated the Inka. Finally, the letter is written in Spanish, two indigenous languages (Quechua and Aymara), and Latin—highlighting the various languages Guaman Poma knew. One might even consider the many images a fifth, purely visual language, one that combined Andean and European systems of representation.

“The hermit priest Martín de Ayala instructs Guaman Poma and his parents in the Christian faith,” from Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala, The First New Chronicle and Good Government (or El primer nueva corónica y buen gobierno), c. 1615, p. 17 (image from The Royal Danish Library, Copenhagen)

A brief biography of Guaman Poma

Born around 1525, Guaman Poma was a descendent of the royal Inka on his mother’s side and the pre-Inka Yarovilka dynasty on his father’s side. He had a half-brother, Martín de Ayala, who was a mestizo (meaning that one of his parents was Spanish) and worked as a priest, eventually converting Guaman Poma’s family to Christianity. He claims that his brother also taught him to read and write.

Because he could read and write in several languages, Guaman Poma worked as an administrator and scribe in the Andean colonial government. On several occasions he attempted to have lands near Huamanga (today, a province in Peru), which were at the center of a dispute, returned to his family. Ultimately, he was exiled from Huamanga after he was charged with falsely claiming he was a noble entitled to these lands.

Guaman Poma also worked with the Mercedarian friar, Martín de Murúa, who had traveled from Spain in the 1580s to Peru to help convert the native peoples of the Andes to Christianity. Murúa completed two different historical chronicles, which included color illustrations, the Historia general del Piru (General History of Peru) and the Historia del origen y genealogía de los reyes Incas del Piru (History of the origin and genealogy of the Inka Kings of Peru, 1590. Guaman Poma completed some of the images in the manuscript known as the Galvin Murúa—attesting to the productive working relationship between these two men (despite Guaman Poma expressing some dissatisfaction with Murúa in his New Chronicle). A distinct advantage of working with Murúa, however, was that it afforded Guaman Poma access to his library—influencing some of the information and drawings contained in his letter to the King.

Guaman Poma the artist

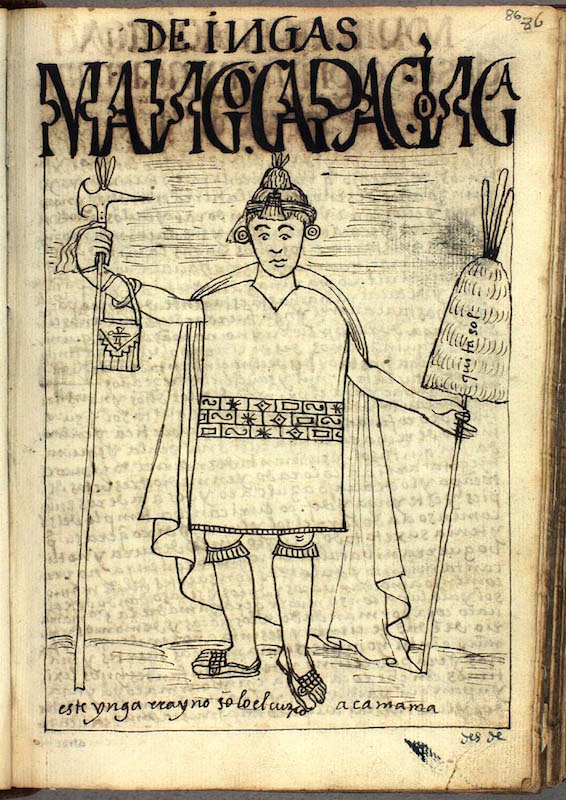

Guaman Poma’s illustrations offer insight into his perception of the Andean past and colonial present. They don’t simply duplicate the text, but often complement it. Throughout his letter, Guaman Poma’s drawings pay scant attention to the details of individual faces, though he does render detailed clothing. For example, some of the most famous illustrations from New Chronicle are those depicting the male Inka rulers (called the Sapa Inka).

The first Inka, Manco Capac Inka, from Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala, The First New Chronicle and Good Government (or El primer nueva corónica y buen gobierno), c. 1615, p. 86 (image from The Royal Danish Library, Copenhagen)

The image of the first Sapa Inka (above), called Manco Capac, shows the ruler standing in the center of the page, dressed in the appropriate regalia for a Sapa Inka. He wears a man’s tunic, called an unku, that has an elaborate, decorative band around his midsection. This is the tocapu, and it is reserved for the Inka ruler as a way to identify him and signal his special status. Manco Capac also wears elaborate sandals, earspools, and a special fringed ornament on his head, called the mascaypacha (and only worn by the Sapa Inka). A cape frames him from behind, and he holds a special staff and a weapon in his outstretched arms.

Maps

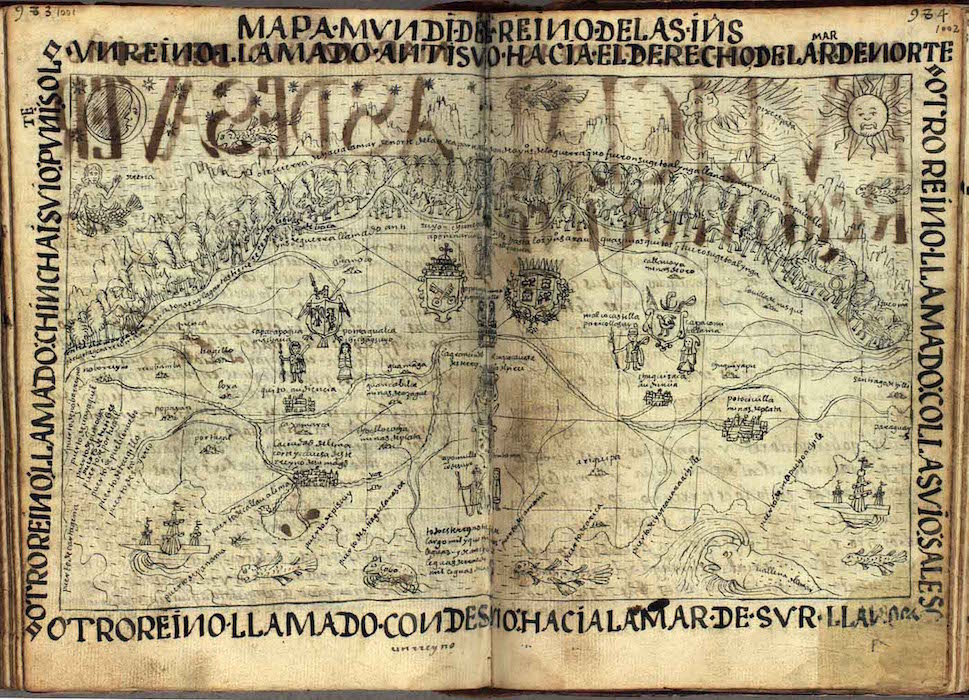

One of the most fascinating images from the manuscript depicts what Guaman Poma titles a “mappa mundi of the kingdom of the Indies” in other words, the Andean region (mappa mundi means “map of the world”).

Mappa Mundi of the Indies of Peru, showing the quatripartite division of the Inka empire of Tawantinsuyu, from Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala, The First New Chronicle and Good Government (or El primer nueva corónica y buen gobierno), c. 1615, p. 1001-02 (image from The Royal Danish Library, Copenhagen)

Detail, Mapa Mundi of the Indies of Peru, showing the quatripartite division of the Inka empire of Tawantinsuyu, from Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala, The First New Chronicle and Good Government (or El primer nueva corónica y buen gobierno, c. 1615, p. 86 (image from The Royal Danish Library, Copenhagen)

Guaman Poma’s map shows the Andean “Indies” divided into four parts, with the Spanish Crown’s coat of arms and the papal (Pope’s) coat of arms at the center. The four parts of the world are based on the earlier Inka division of their empire, known as Tawantinsuyu, or realm of the four quarters. Each realm had a different name, and was associated with specific ethnic groups. In Poma’s mappa mundi, we see each region represented by a male and female couple, along with a coat of arms representing the quarter. Important cities are labeled, along with rivers and mountains.

For example, in the realm to the left of center, known as Chinchaysuyu, we see the Audiencia of Quito (an administrative unit in the Spanish Empire) labeled just below the ruling couple (left). Fantastic beasts like unicorns, monkeys, hairy men, and creatures reminiscent of dragons and large flying fish, dot the fringes of the land. A mermaid waves below the moon on the upper left corner. While some of these spatial conventions and fantastical creatures borrow from medieval European mapping traditions, Guaman Poma blends them with Andean concepts of space and symbols.

The Symbolism of Space

Throughout his manuscript, Guaman Poma uses space to communicate Andean notions of power—specifically the complementary concepts of hanan (upper) and hurin (lower). The mappa mundi offers a nice example of these concepts. The couple in the center is the Sapa Inka Tupac Yupanqui (an early Inka king) and his coya (queen consort) Mama Ocllo (who was also his sister). The suyus, or regions, of Chinchaysuyu and Antisuyu represent hanan (upper) positions, while Cuntisuyu and Collasuyu are hurin (lower). While the hanan regions are considered superior, they also complement the lower regions. Neither could exist without the other, and represent broader binary yet complementary concepts like male/female or left/right. Another example of this complementary relationship between hanan and hurin can be seen in the plan of the Inka capital Cusco.

Guaman Poma uses these spatial concepts in other ways in his manuscript—sometimes to draw attention to someone’s importance. For instance, on the frontispiece of the manuscript (top of page) the pope is in the hanan position (reader’s left, but right side of the page), while the Spanish king and Guaman Poma are in the hurin position. In this way, Guaman Poma likely intended to convey the superiority of the Pope.

The Conquest, Civil War, and Revolts

In chapter 19 of New Chronicle, Guaman Poma recounts the Spanish Conquest and ensuing civil wars that erupted in the Andes. The images accompanying the text reveal the Spanish lust for gold and some of the key events of the Conquest.

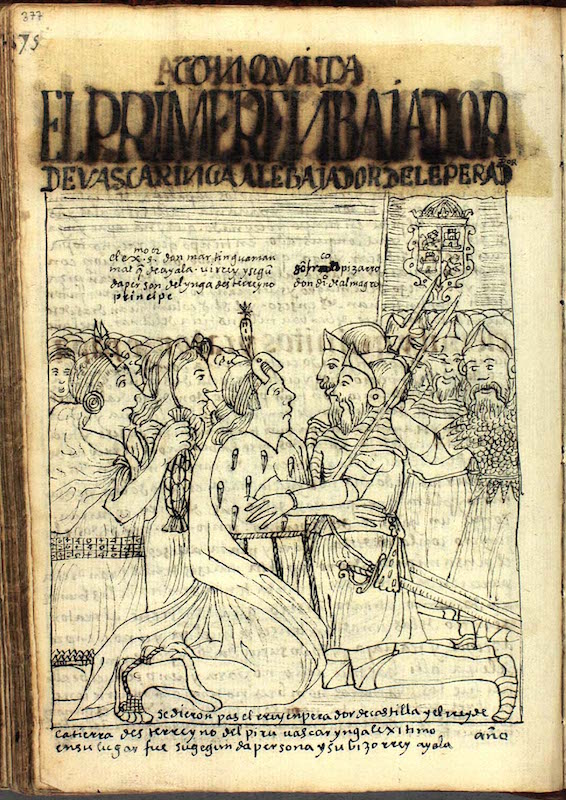

“Don Martin de Ayala, the first ambassador of Huascar Inka and father of Guaman poma, greets Don Francisco Pizarro and Don Diego de Almagro, ambassadors of the Spanish king,” from Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala, The First New Chronicle and Good Government (or El primer nueva corónica y buen gobierno), c. 1615, p. 377 (image from The Royal Danish Library, Copenhagen)

In one we see the Spanish conquistadors Francisco Pizarro and Diego Almagro, dressed in Spanish armor and leading troops (p. 373). Another image (above) shows the same conquistadors as they interact with Guaman Poma’s father, Don Martin de Ayala, who is noted as an ambassador to the Sapa Inka, Huascar Inka.

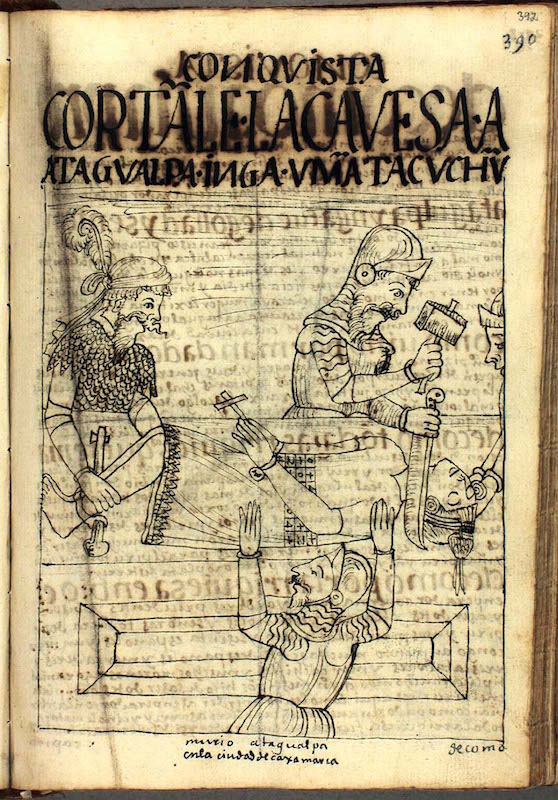

“The execution of Atahualpa Inka in Cajamarca: Umanta kuchun, they behead him,” from Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala, The First New Chronicle and Good Government (or El primer nueva corónica y buen gobierno), c. 1615, p. 386 (image from The Royal Danish Library, Copenhagen)

One of the most disturbing scenes of the Conquest is the beheading of Sapa Inka Atahualpa in the city of Cajamarca (above). Huascar Inka and Atahualpa were brothers who both sought to control the Inka Empire after their father died. Eventually, Atahualpa would defeat his brother during a civil war, and Atahualpa would then be captured by Pizarro. The illustration of Atahualpa’s execution shows him bound on a hard surface, his hands clasping a cross—a reference to his conversion to Christianity just prior to his death. A Spanish soldier holds a knife to his neck, as well as a mallet. Atahualpa’s eyes are closed, signaling that he is dead. The illustrations from this chapter portray the complexity and chaos of this time.

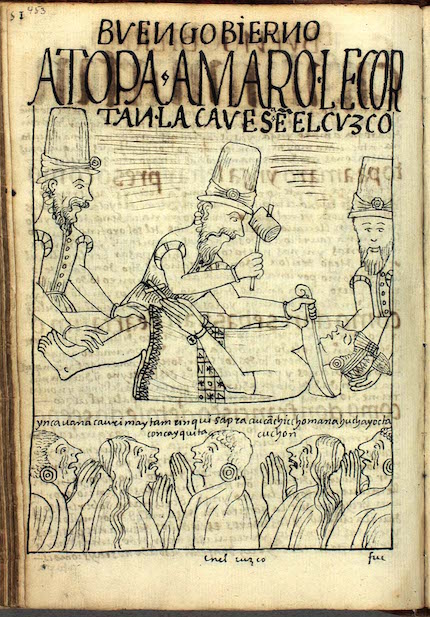

“The execution of Tupac Amaru Inka by order of the Viceroy Toledo, as distraught Andean nobles lament the killing of their innocent lord,” from Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala, The First New Chronicle and Good Government (or El primer nueva corónica y buen gobierno), c. 1615, p. 453 (image from The Royal Danish Library, Copenhagen)

The following chapter details “good government” after the Spanish Conquest. In one illustration, we see the capture of Tupac Amaru Inka (p. 451), who led a series of revolts against the Spaniards as he and others attempted to retain an Inka state or empire free of the Spaniards.

Another image (left) shows Tupac Amaru’s execution in 1572, which mimics the death of Atahualpa Inka during the Conquest. Guaman Poma used the same basic composition and motifs, but this time with Tupac Amaru’s prone body resting above a group of weeping Andean peoples to highlight their suffering.

Tupac Amaru’s death is considered the end of the Conquest though he would remain a symbol of protest and revolt in the Andes throughout the colonial period, specifically the uprising led by Tupac Amaru II in the eighteenth century. (Fun fact: the hip-hop artist Tupac Shakur was named after Tupac Amaru II).

It is impossible to discuss all aspects of Guaman Poma’s Chronicle, but hopefully this essay provides a sense of the importance of his letter as a resource for learning about Inka and colonial Andean culture. While it never made its way into the hands of the Spanish king, and was never published and distributed as Guaman Poma intended, today the manuscript is available in its entirety online from the Royal Library of Denmark, where the original Chronicle is kept.

Additional resources:

A facsimile of the Historia general del Piru (also called The Getty Murúa)

Essays on The Getty Murúa from the Getty Museum

Rolena Adorno, Guaman Poma: Writing and Resistance in Colonial Peru (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2000).

Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala, The First New Chronicle and Good Government, trans. Roland Hamilton (Austin: University of Texas PRess, 2009).

Guaman Poma de Ayala: The Colonial Art of an Andean Author (NYC: Americas Society, 1992).

Lauren Kilroy-Ewbank, “For all the world to see: Guaman Poma’s Self-Portraits in Nueva corónica,” The Americas: A Quarterly Review of Latin American History 75, no.1 (January 2018): 47–94.