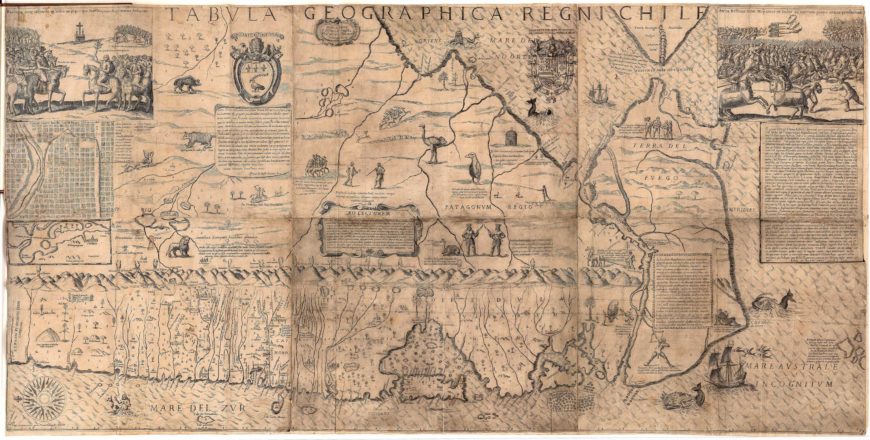

Alonso de Ovalle, Tabula geographica regni Chile, 1646, 57 x 116 cm (John Carter Brown Library, Brown University)

What images might enhance a map of a distant land in a remote corner of the world? Might lava-spewing volcanoes, a strutting penguin, and gold mines captivate your attention? All of these fascinating miniatures and more embellished one of the earliest maps of Chile that was disseminated in Europe.

In 1646, a Chilean man named Alonso de Ovalle published an illustrated text titled Historical account of the Kingdom of Chile (Histórica relación del reyno de Chile) to inform Europeans of the history and characteristics of his homeland, and he created a pictorial map of Chile to accompany it. More accurately, Ovalle produced two versions of his map of Chile, a smaller rendition that was bound within most copies of his book, and a larger and more detailed version that we know of through only two extant copies. One copy of the larger map (measuring 57 x 116 cm) is in the collection of the John Carter Brown Library, and it is called the Tabula geographica regni Chile. [1]

From 1542 until 1818, Chile was part of the administrative district of the Viceroyalty of Peru, one of four viceroyalties that Spain created in the Americas to better govern the population. The Viceroyalty of Peru was governed from Lima, and in Ovalle’s day consisted of nearly the entirety of South America (beyond Brazil, which was controlled by Portugal). During the eighteenth century, as Spain established two additional viceroyalties in South America, the Viceroyalty of Peru was reduced to what are now the nations of Chile, Peru, and Bolivia.

Alonso de Ovalle was born in approximately 1601 to an elite family in the Chilean capital, and in 1618 he joined the Jesuits. In 1640 he became the first Jesuit to hold the newly created office of Chilean procurator general (a religious diplomat) to Rome and Spain, and he passed the years 1642–1650 carrying out this office in Europe.

Taking advantage of the presses in Rome, Ovalle created his book and his maps describing Chile to attract missionaries and royal investors in support of Jesuit efforts there. His published works also exemplify the zealous pride of homeland that characterized many criollos (American-born peoples of European heritage). Criollos such as Ovalle felt a deep attachment to the Americas, and a desire to convey to Europeans how their particular homelands were uniquely wonderful places marked by productivity and wealth.

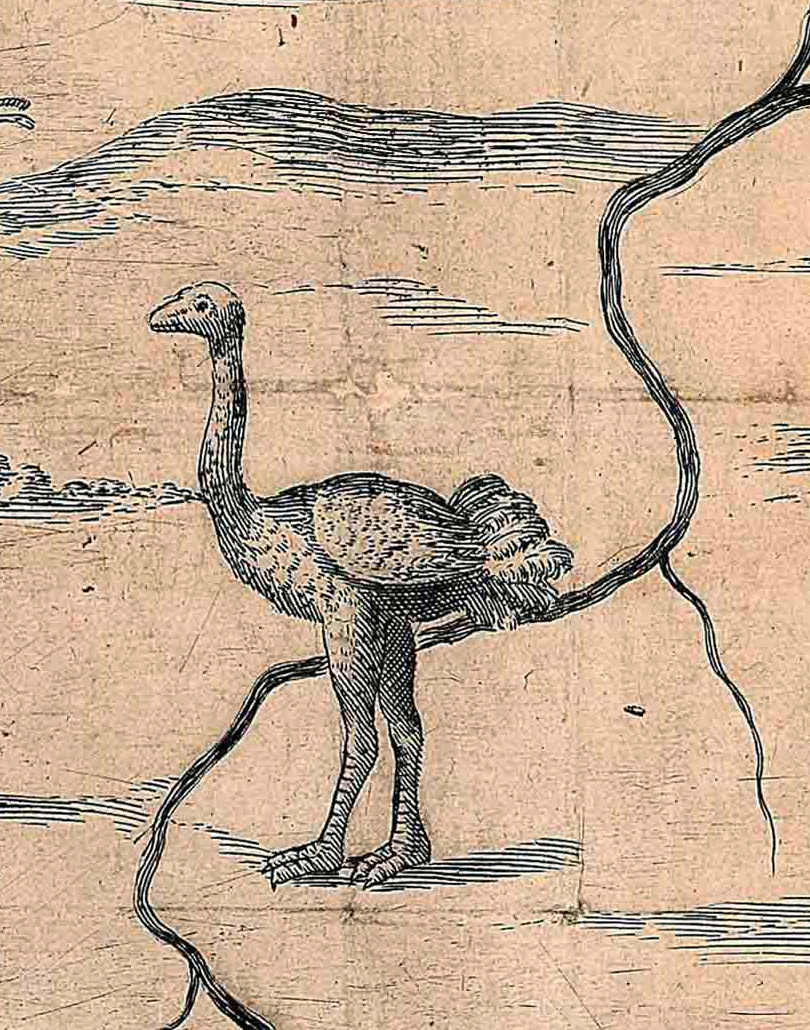

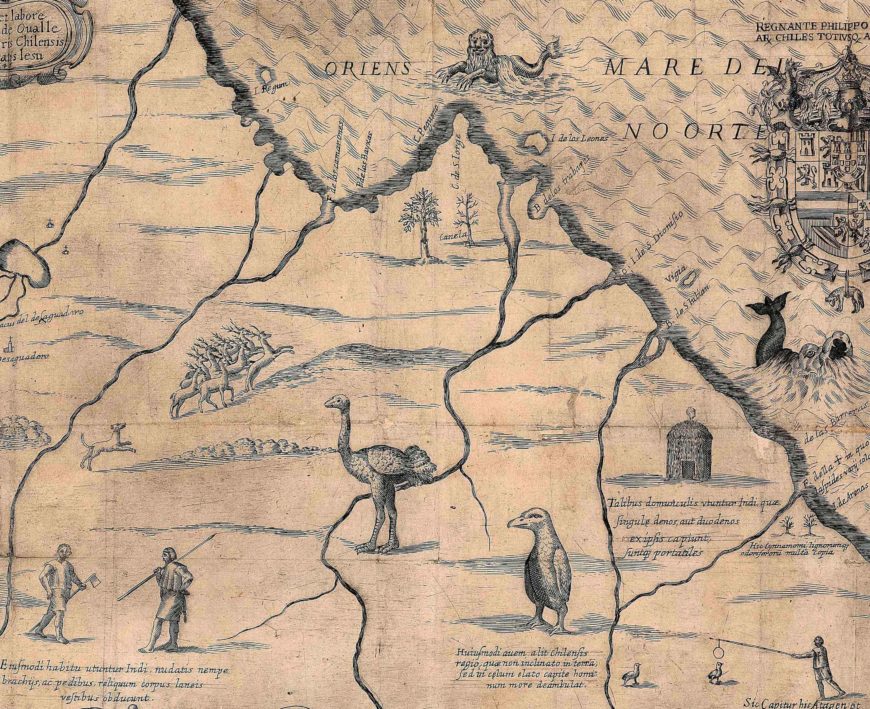

Animals roam the lands, including deer, a nañdú or rhea (which looks like an ostrich), and a penguin to the right. Detail of Alonso de Ovalle, Tabula geographica regni Chile, 1646, 57 x 116 cm (John Carter Brown Library, Brown University)

The significance of the Tabula geographica

Ovalle’s Tabula geographica is significant for various reasons, including its rarity as an early cartographic visualization of Chile. As Spain’s most remote territory in the Americas, primarily accessible via the treacherous Strait of Magellan or overland routes across Argentina, Chile maintained an insularity during the seventeenth century that limited knowledge of its geography and characteristics in Europe. As a further complication, because Chile did not obtain a printing press until the early nineteenth century, we currently have few maps of this region from the colonial era by Chilean authors. This is one reason why Ovalle’s map is so important. He provided detailed information about a land that was inaccessible to many. In his map, Ovalle also inserted tiny images of local flora, fauna, geographical characteristics, and Indigenous practices (past and present), allowing viewers to associate the features of the area with the particular regions where they occur.

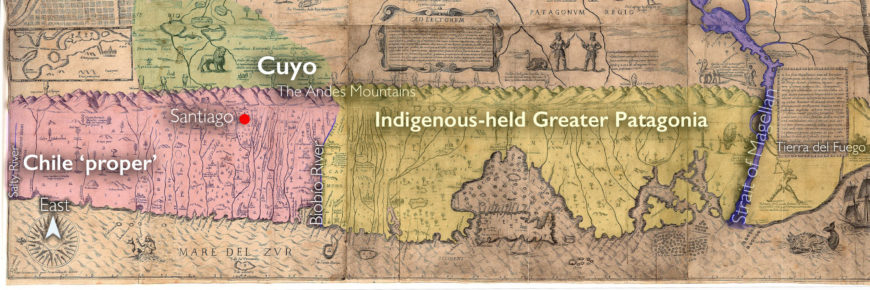

Detail showing ‘Chile proper’ at lower left, Cuyo just across the Andean cordillera, and southern Chile from Patagonia southward. Alonso de Ovalle, Tabula geographica regni Chile, 1646, 57 x 116 cm (John Carter Brown Library, Brown University)

Organization

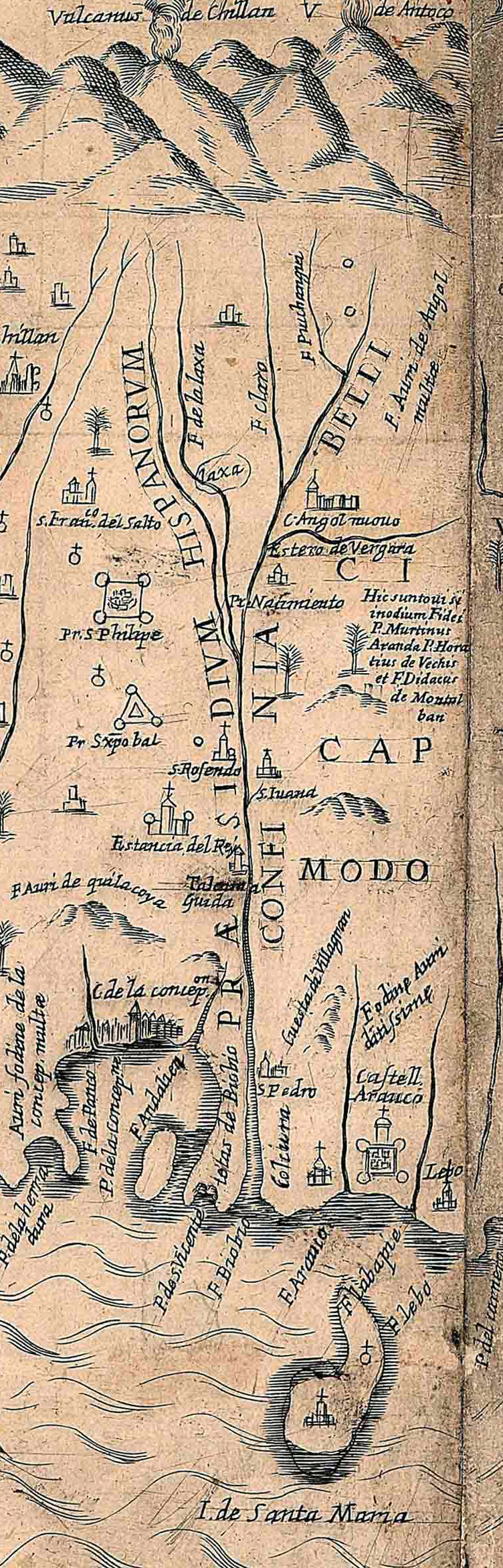

The large version of the Tabula geographica regni Chile is a horizontal east-up map (meaning that the map is oriented with the east at the top) showing Chile in three sections. The first section is “Chile proper,” a narrow ribbon of land confined by the natural limits of the Andean cordillera (the mountain range) to the east and the Pacific Ocean to the west, as well as by the Peruvian border at the Salty River (Río Salado) to the north and frontier with the Indigenous Mapuche (who live in Chile and Argentina) and their neighbors at the Biobío River (Río Biobío) in the south. The second region indicated in the Tabula geographica is Cuyo, a province located east of the Andes that pertained to the Diocese of Santiago de Chile.

The third area, by far the largest of the three, was located south of the Biobío River and was not formally part of Chile at the time the map was made. Comprised of the vast terrain of Patagonia down to the Strait of Magellan and Tierra del Fuego, Ovalle conveyed this section as a potential region of southward Spanish expansion.

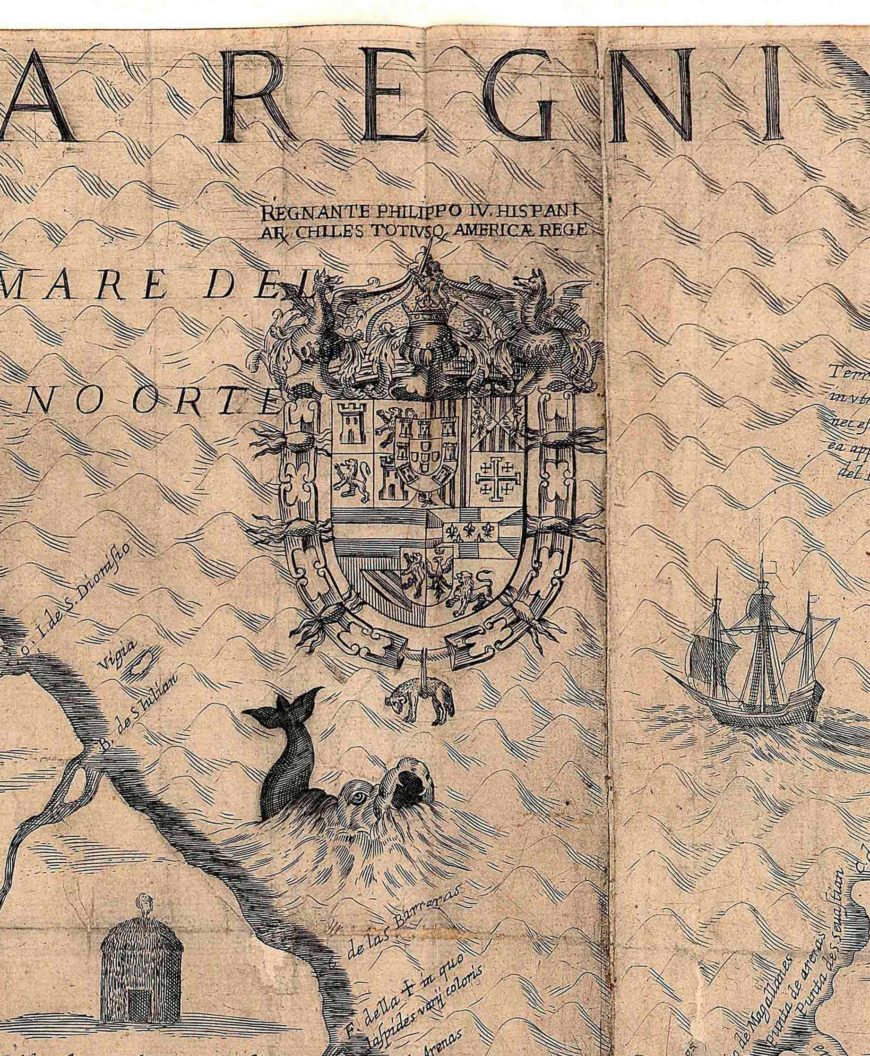

The coat of arms of Philip IV, with insignia of the Order of the Golden Fleece (including the ram pendant), threatened by a sea monster. Detail of Alonso de Ovalle, Tabula geographica regni Chile, 1646, 57 x 116 cm (John Carter Brown Library, Brown University)

In the upper area of the map, Argentina provides a backdrop for additional images and symbols. For instance, the Spanish royal coat of arms and the papal coat of arms are arranged beneath the title. Here Ovalle inserted a bit of comic relief at the expense of the Spanish King, Philip IV; a playful detail shows a sea monster poised to devour the ram pendant dangling from the collar of the Order of the Golden Fleece that frames his coat of arms, as if to attack the very emblem of the Crown’s authority.

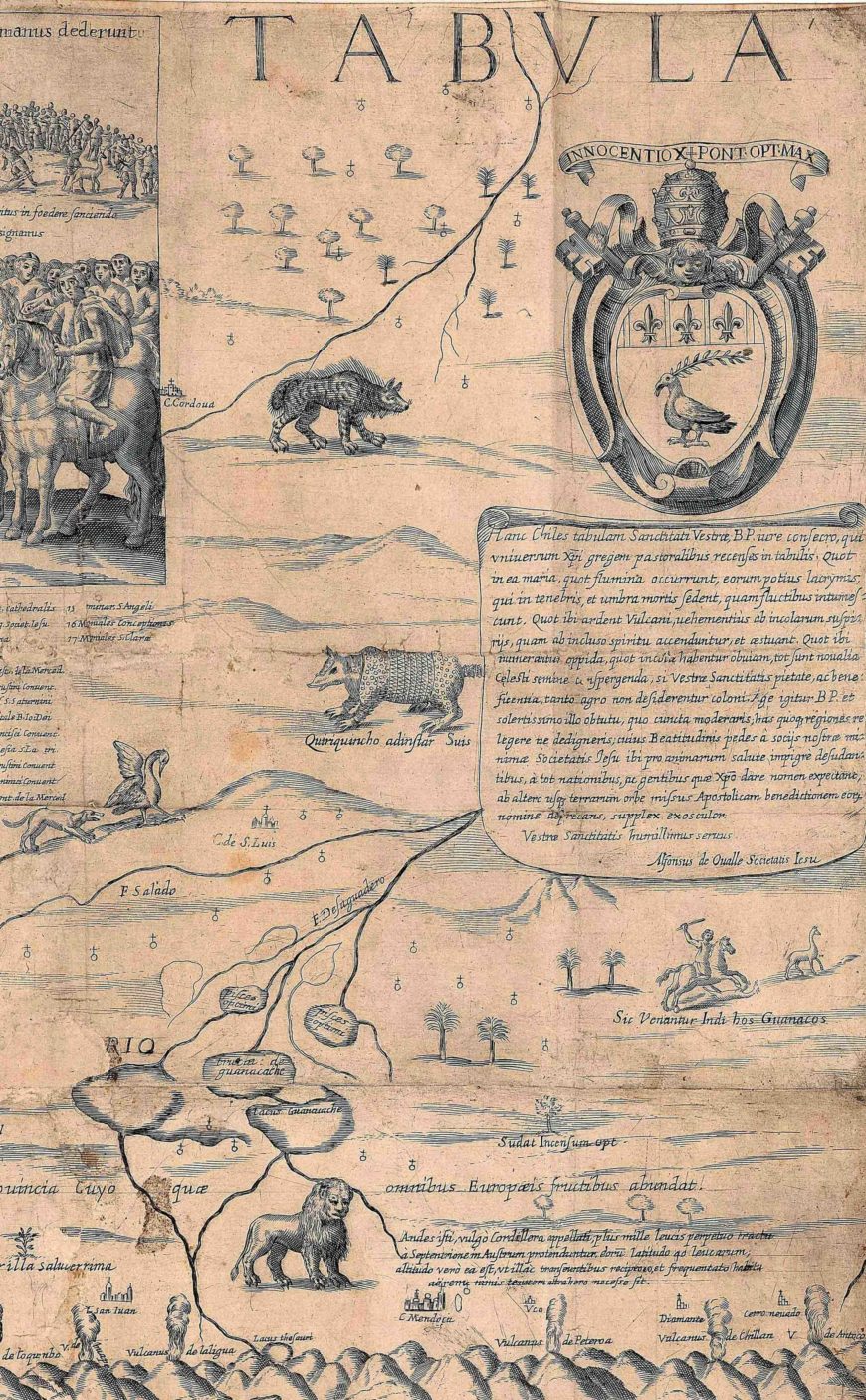

Lively beasts roam Argentina including an armadillo (called a quirquincho in Chile; center), a lion-like puma (bottom), and different birds. A hunting scene appears on the right side. Detail of Alonso de Ovalle, Tabula geographica regni Chile, 1646, 57 x 116 cm (John Carter Brown Library, Brown University)

Mapped Iconographies

The Biobío River and the Spanish forts San Cristóbal (triangular) and San Filipe (rectangular). Detail of Alonso de Ovalle, Tabula geographica regni Chile, 1646

Miniature illustrations bring Ovalle’s map to life and offer insight into his perceptions of the benefits and comforts of Chile. These tiny pictures also helped Europeans to envision Chile as a comfortable and productive land that was like Spain and Italy in many ways, yet also contained fascinating features that were unknown in Europe. Among these depicted features, mineral wealth in the form of mines and medicinal plants are dispersed throughout “Chile proper.”

In Patagonia (specifically in Tierra del Fuego), images such as an Indigenous man with a tail suggest mythologies adapted from other maps and prints, for instance from the illustrations produced during the early seventeenth century under the voyage of Dutch explorer Joris van Spilbergen. Lively beasts roam Argentina; we can identify an armadillo (called a quirquincho in Chile), a lion-like puma, a penguin, and a relative of the ostrich called a nañdú (all of which are visible in different images throughout this essay).

Hunting scenes are also featured, involving wild animals rarely encountered in Europe and Indigenous techniques for tracking or trapping them. Hunting is often a veiled metaphor for militarism, and it is no surprise that the Spanish effort to conquer and Christianize the Indigenous south is also expressed in the Tabula geographica. The Arauco War, as this long-running effort was termed, is signaled by the Spanish forts along the Biobío River and narrated by paired scenes of war and peace in the map’s upper corners. The Biobío River was the contentious border between Spanish-held Chile and the Indigenous southern region, labeled in the map as PRAESIDIUM HISPANORUM (Spanish garrisons) on the north and CONFINIA BELLI (limits of war) on the south. The Spanish forts San Cristóbal (triangular in shape) and San Filipe (rectangular in shape) are seen just north of the river.

In the background of the battle scene in the upper right corner, Spanish canons shoot at Indigenous forces who hold bows. The rest of the print shows a chaotic battle scene. Alonso de Ovalle, Tabula geographica regni Chile, 1646. Image from the John Carter Brown Library, Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island.

The battle scene at the upper right corner juxtaposes Spanish canons with Indigenous bows to suggest Spanish dominance. By contrast, the upper-left inset commemorates a peace treaty established in 1641 between the Governor of Chile and a Mapuche leader. Ovalle included these scenes because he wanted to express to the King of Spain and to the Pope that Chile had entered an era of peace with the neighboring indigenous peoples, an ideal moment for amplifying Jesuit efforts to convert this population to Christianity.

The Peace Treaty of Quillín of 1641 between Spanish and Mapuche authorities. Detail of Alonso de Ovalle, Tabula geographica regni Chile, 1646, 57 x 116 cm (John Carter Brown Library, Brown University)

Complex histories and meanings

As early modern pictorial cartographies of the Spanish Americas became more widely appreciated during the twentieth century, scholars began to study the diversity of meanings and functions that they held for their makers and audiences as well as the sources that inspired them. The Histórica relación del reyno de Chile has been reissued by several Chilean historians, sparking renewed interest in examining the details of the Tabula geographica. The commentaries of these historians have led to new information, providing a better understanding of the complex histories and cultural meanings embedded in this map. Today scholars recognize that meanings of colonial-era cartography shift across regions and audiences, and that Ovalle, a Mapuche cacique (tribal leader), a Spanish King, a Pope, and prospective Jesuit missionary would have each read the Tabula geographica in a very different way.

Notes:

[1] The other large map is preserved in Paris at the Bibiothèque nationale de France as a loose sheet measuring 68 x 121 cm.

Additional Resources

The Tabula geographica regni Chile (1646) by Alonso de Ovalle at the John Carter Brown Library, at Brown University, Rhode Island

The Tabula geographica regni Chile (1646) by Alonso de Ovalle at the Bibiothèque Nationale de France

Alonso de Ovalle, Histórica relación del Reyno de Chile y de las missiones y ministerios que exercita en el la Compañía de Jesús (Rome: Francisco Cavallo, 1646).

Catherine Burdick, “The remedies of the machi: visualizing Chilean medicinal botanicals in Alonso de Ovalle’s Tabula geographica (1646),” Colonial Latin American Review vol. 26 no. 3 (2017), pp. 313–334.

Alejandra Vega Palma, “La Tabula geographica regni Chile de Alonso de Ovalle,” en Histórica relación del Reyno de Chile y de las missiones y ministerios que exercita en el la Compañía de Jesús (Santiago: Patrimonio Cultural de Chile, 2012), pp. 63–70.

Lawrence C. Wroth, “Alonso de Ovalle’s Large Map of Chile, 1646,” Imago Mundi vol. 14 (1959), pp. 90–95.