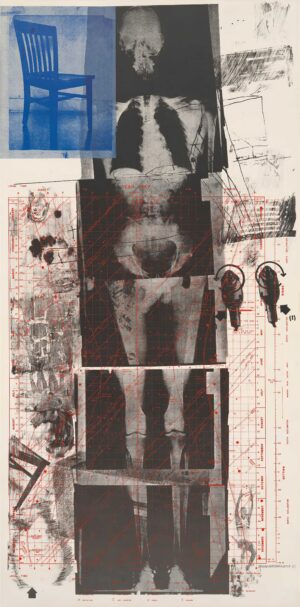

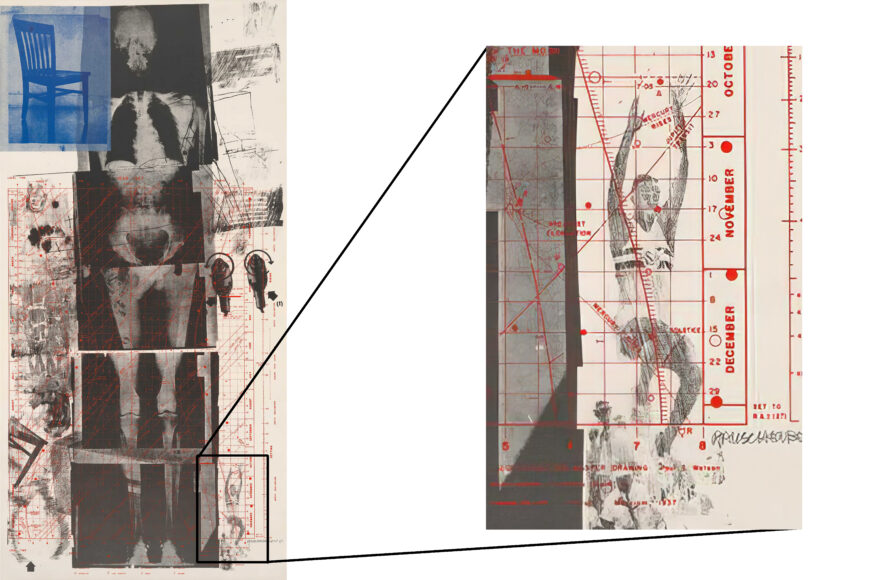

Robert Rauschenberg, Booster, 1967, lithograph and screen print, 181.7 x 89.3 cm, printed by Gemini G.E.L., Los Angeles (The Museum of Modern Art, New York) © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation

Robert Rauschenberg’s Booster is an unusual work of art, and viewers are likely to be struck by the cobbled together X-ray images that form a life-sized skeleton. These appear as though stacked along the large-scale print’s vertical axis, their dark, rectangular segments echoing the shape most often associated with pictures, screens, and printed materials. Because of these and other overlapping images, this work could even be read as a form of printed collage—an artwork created by cutting and pasting that typically features pop culture sources such as newspapers and magazines. The stacked X-rays also create a door-like frame from which the skeletal figure aligns with the viewer’s own body. Although perhaps a bit disquieting, the figure’s alignment with our position in front of the work, combined with the overlapping imagery of everyday life that includes other references to the human body, invites us to engage with this intriguing composition.

Booster is sometimes described as a self-portrait because Rauschenberg created its most striking feature by reproducing X-rays of himself. But the artist appears to be playing with and inverting our ideas about what portraiture and even what art can be. Whereas portraiture’s disparate histories have been characterized by realism, surface beauty, or imagined psychological depth, Booster uses the scientific medium of X-rays, routine medical images that reveal the body’s interior structure. Booster nods to the tradition of representational portraits by focusing on a body, but does so without employing the artistic skill needed to create illusionistic figures on two-dimensional surfaces such as paintings. In doing so, Rauschenberg’s print celebrates neither the presence of the artist’s hand nor an idealized representation of the body, longstanding tenets of Western art since the Renaissance.

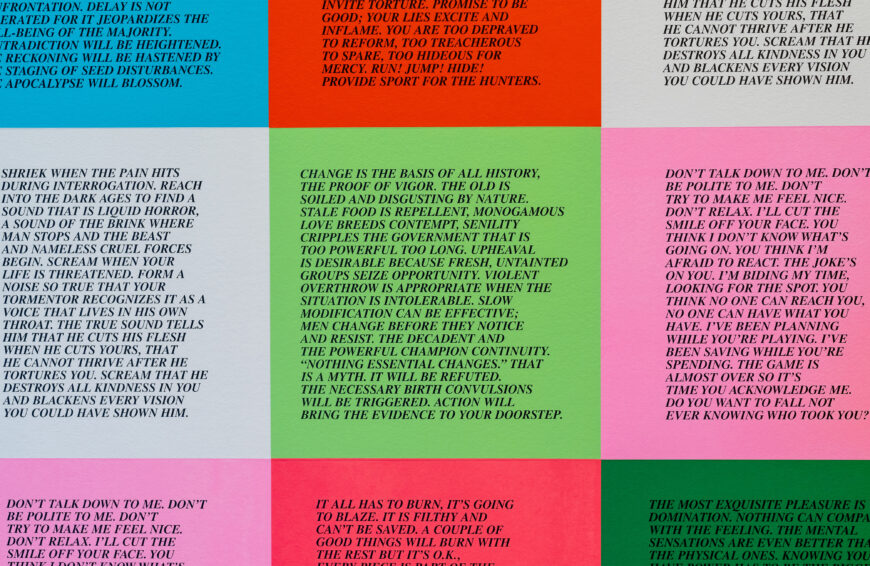

Experimenting with art history

The idea of artistic presence had been taken up by many artists working in abstraction during the 20th century, including the post WWII American painters known as Abstract Expressionists. They believed their expressive, sometimes sketch-like brushwork and signature styles revealed inner creativity. Rauschenberg makes a nod to this history, which opened the door to experimental art in the United States, but his scribbly marks also recall ordinary drawings such as diagrams, sketches, and graffiti.

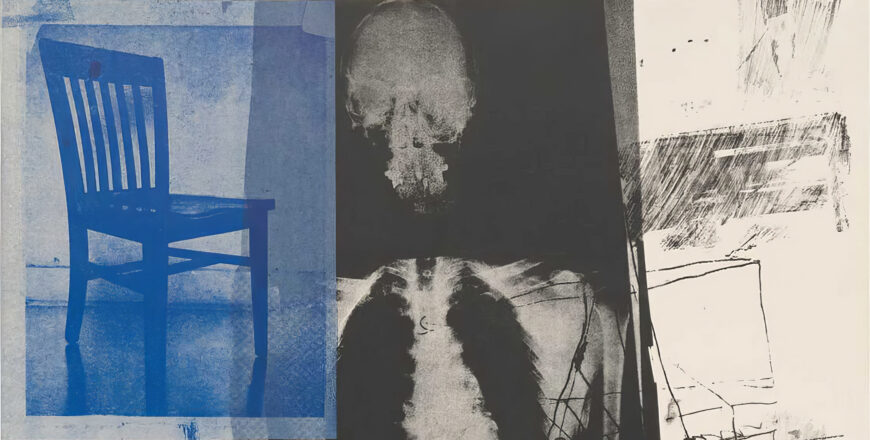

Chair, X-ray of a skull, and scribbly marks (detail), Robert Rauschenberg, Booster, 1967, lithograph and screen print, 181.7 x 89.3 cm, printed by Gemini G.E.L., Los Angeles (The Museum of Modern Art, New York) © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation

Although Booster pays homage to portraiture, photography, and even Abstract Expressionism, the work simultaneously subverts these genres and the imagined relationship between the artist, the work, and the viewer. Booster even plays with the tradition of memento mori—artworks that feature skulls and other signs that remind the viewer of the inevitability of death. As many critics and art historians have noted, however, Rauschenberg’s work avoids being overly expressive or sentimental. Although it suggests layers of memory, it rarely instigates nostalgia. Instead, as critic Leo Steinberg asserts, it calls to mind the “flatbed picture plane,” a term that references printmaking, visual culture, and the cobbler’s workbench rather than the so-called “high art” that for centuries characterized museums, galleries, and private collections. [1]

X-ray of legs overlaid with charts and other images (detail), Robert Rauschenberg, Booster, 1967, lithograph and screen print, 181.7 x 89.3 cm, printed by Gemini G.E.L., Los Angeles (The Museum of Modern Art, New York) © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation

A deadpan irony abounds in Rauschenberg’s choice of imagery in Booster that peers beneath the skin and his use of his body directly (or at least in copies), rather than pictorially or performatively to create art. In fact, the themes of the body, lived experience, and art operating in tandem with ordinary visual culture run throughout much of Rauschenberg’s oeuvre, as does his effort to work in the “gap” between art and life for which he often turned to printmaking, mixed-media collage, and its three-dimensional form known as assemblage. [2]

Tire print (detail), Robert Rauschenberg and John Cage, Automobile Tire Print, 1953, paint on 20 sheets of paper mounted on fabric, 41.9 x 726.4 cm (San Francisco Museum of Modern Art) © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation

In exploring these themes, Booster appears to also be in a kind of dialogue with the form of the readymade, a term coined by early 20th-century Dada artist Marcel Duchamp. Rauschenberg and many of the artists with whom he collaborated in the mid-20th century were referred to as Neo-Dada because they, like their early 20th-century counterparts, combined a variety of media and art forms—including performance, readymades, and printed materials—in order to simultaneously intrigue the viewer and resonate with lived experience. The improvisational tactics in works such as Booster show the influence of Dada artists, transmitted primarily through Rauschenberg’s friend, the experimental composer John Cage. As a young artist, Cage befriended Duchamp, and in turn, Cage’s innovative practice had a profound impact on the avant-garde art scenes in New York, Black Mountain College in North Carolina, and internationally.

Robert Rauschenberg, Canyon, 1959, oil, pencil, paper, metal, photograph, fabric, wood, canvas, buttons, mirror, taxidermied eagle, cardboard, pillow, paint tube and other materials, 207.6 x 177.8 x 61 cm (The Museum of Modern Art, New York) © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation

Rauschenberg’s work suggests more of an interest in artmaking using the literalness of his diverse materials and cultural sources, rather than the irreverence, clever parody, and shock value that occupied many of the Dada artists. He became well known for his Combines, an example of which is Canyon, which joined painted marks, images, real-world objects, including detritus, and even text. These recall some of the sensibility of recycling in the early 20th-century Dada of Kurt Schwitters. Yet, Rauschenberg refrains from translating cast-off rubbish into formally beautiful compositions. Instead, his layered, messy amalgamations confront us with emphatic materiality. Although Booster is a print, it is no exception.

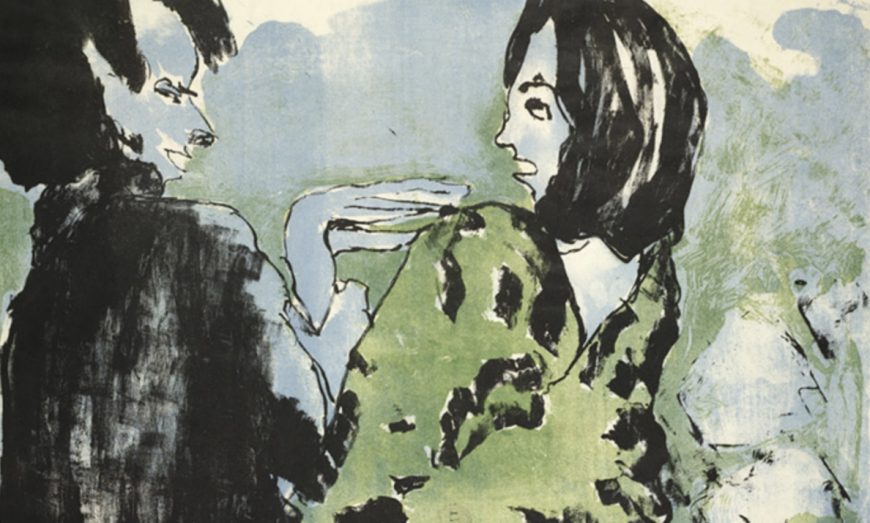

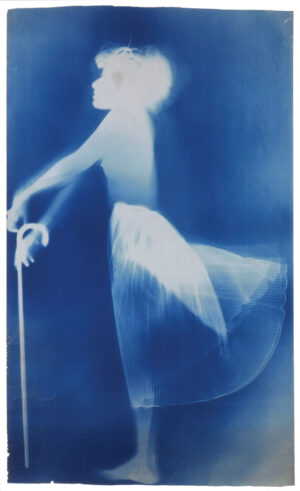

Robert Rauschenberg and Susan Weil, Sue, c. 1950, cyanotype, 177.2 x 105.7 cm (private collection) © Susan Weil and Robert Rauschenberg Foundation

Printmaking and the body

Rauschenberg began experimenting with printmaking and the use of the body early in his career, when he and his then companion, artist Susan Weil, created life-sized works they called Blueprints. The artists produced these works by lying on paper treated with cyanotype chemicals, creating a blue background on any surface not covered by the artists’ bodies. Booster appears to transform this early engagement with printmaking using Rauschenberg’s own body, now in X-rays that penetrate it to make its inside visible.

The overlapping images taken from print media and the scribbly hand-marks that are possible using a lithographic process are also interesting to consider. The transfer process Rauschenberg developed during the 1950s, in which he soaked images, placed them face down onto paper, and rubbed the backs until the images appeared on the paper, was readily adaptable to create transfer lithography. This and the screen printing process allowed him to integrate expressive marks with the literal imagery of visual culture that in Booster includes basketball players and chairs—images that, along with the X-rays, charts, graphs, and the mechanical devices of industry, reference the human body and its movements in culture.

Basketball player in the margin (detail), Robert Rauschenberg, Booster, 1967, lithograph and screen print, 181.7 x 89.3 cm, printed by Gemini G.E.L., Los Angeles (The Museum of Modern Art, New York) © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation

The imagery in the long, wide margins that frame the central figure appears to be in dialogue and also relates to the themes of the body, movement, and the acts of making, doing, or observing. A basketball player jumps to make a shot at the bottom right while another appears, inverted and truncated, at the upper left. These figures are small, perhaps suggesting the flitting imagery in print media and increasingly in the television and advertising of postwar consumer culture. The athleticism of these players again suggest movement and perhaps even the experimental theater and dance performances Rauschenberg participated in with other Neo-Dada artists, combining elements of art and ordinary life.

With collage as a guiding principle, Rauschenberg made no attempt to precisely align these figures or their orientation with regard to the X-ray or other compositional fragments. Instead, he let the improvisational, layering effects show, as though echoing the complex transience of lived experience.

Upper left chair (detail), Robert Rauschenberg, Booster, 1967, lithograph and screen print, 181.7 x 89.3 cm, printed by Gemini G.E.L., Los Angeles (The Museum of Modern Art, New York) © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation

Layers of references

The chairs in the print, most prominently the one in blue at the upper left of the work, also reference the body and the artist’s own body of work. Rauschenberg used readymade chairs in a number of his three-dimensional assemblages and incorporated drawn and photographed chairs in several of his prints. He would have also been aware of the use of chairs in other notable artworks, including Joseph Kosuth’s conceptual art installation One and Three Chairs, of 1965, which featured an actual chair, a photograph of the chair, and wall text with the definition of a chair. Rauschenberg would have also been aware that a readymade chair featured prominently in Joseph Beuys’s Fat Chair, a chair topped with a large slab of fat first created in 1964, which itself refers to the chair as a kind of portraiture and a marker of absence and loss, echoing the use of empty chairs as portraiture and self-portraiture in paintings by Vincent van Gogh.

The themes of repetition and appropriation (the recycling of existing images) feature prominently in both visual culture and Rauschenberg’s art practice. In addition to reusing images from popular sources in this piece, he also culled elements of Booster to produce other prints. From Booster, he took seven different elements and put each of them into a different work using different lithographic plates, creating a series referred to as Seven Studies. Overall, Rauschenberg’s gritty combinations of art and visual culture fueled practices of cultural and artistic critique that we still see in 21st-century art.