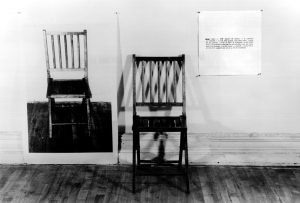

Joseph Kosuth, One and Three Chairs, 1965, wood folding chair, mounted photograph of a chair, and mounted photographic enlargement of the dictionary definition of “chair” (MoMA)

You would not be wrong, standing in front of One and Three Chairs, to think, “there is not much to see here.” This work by Joseph Kosuth consists of a wooden folding chair placed against the wall flanked by two prints: a black and white photograph of the chair, and a photostat of its dictionary definition. Nevertheless, One and Three Chairs is a defining work of conceptual art, a movement that emerged in the mid-1960s and advocated a radically new form of artwork: one whose value, meaning and existence was rooted in its concept, rather than in the work’s physical or material properties.

In Minimalism’s wake

Donald Judd, Untitled (Stack), 1967, lacquer on galvanized iron, twelve units, each 22.8 x 101.6 x 78.7 cm, installed vertically with 9″ (22.8 cm) intervals (MoMA)

Questions of form (the visual elements of works of art) had been paramount for many modern artists during the twentieth century and especially post-World War II, when New York City replaced Paris as the center of the most advanced art of the time. Modernism’s focus on pure form (works of art that sought to contain no references or likenesses to the external world and focused instead on their own inherent visual and material aspects) reached a peak in the 1960s with Minimalism, the movement that directly preceded conceptual art.

For the Minimalists, art’s role was no longer to render scenes of nature, spirituality, or humanity, as had been central to Western art since before the Renaissance, or even to celebrate the artist’s vision and hand as had been the case with Abstract Expressionism. The credo of Minimalist art was “what you see is what you see.” With these pure forms, art was emptied of all other meaning. It was as if the word “sculpture” needed quotation marks. It certainly strained credulity to imagine an industrially-fabricated object made from lacquered, galvanized iron as the equal to the historic sculptural processes such as carved marble or cast bronze produced by Donatello or Bernini.

“Art After Philosophy”

Joseph Kosuth, One and Three Chairs (detail), 1965, wood folding chair, mounted photograph of a chair, and mounted photographic enlargement of the dictionary definition of “chair” (MoMA)

By the end of the 1960s, these Minimalist practices were being challenged. Minimalism’s value remained tied directly to the physical object—a visual form that invited viewers to see it, walk around it, and enjoy its aesthetic qualities. Conceptual artists like Kosuth wanted to downplay the pleasures associated with looking at art as part of a rejection of what they saw as outdated ideas about beauty. While retaining Minimalism’s critical stance toward traditional art forms, they wanted to engage with the unseen relationships that Minimalism had put aside: ideas, signification, and the construction of meaning. “Being an artist now means to question the nature of art,” Kosuth wrote in his 1969 essay “Art After Philosophy.” To this end, he created works that directed the viewer away from form and toward the ideas that generated them.

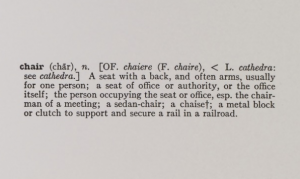

In the case of One and Three Chairs, the central idea was to explore the nature of representation itself. We know instinctively what a “chair” is, but how is it that we actually conceive of and communicate that concept? Kosuth presents us with a photograph of a chair, an actual chair, and its linguistic or language-based description. All three of these could be interpreted as representations of the same chair (the “one” chair of the title), and yet they are not the same. They each have distinct properties: in actuality, the viewer is confronted with “three” chairs, each represented and experienced—read—in different ways.

Semiotics

Joseph Kosuth, One and Three Chairs (detail), 1965, wood folding chair, mounted photograph of a chair, and mounted photographic enlargement of the dictionary definition of “chair” (MoMA)

Kosuth was influenced by new theories of language and signification that had emerged in the early twentieth century, particularly semiotics—the study of the meaning of signs (words or symbols used to communicate information). Semiotics grew out of the science of linguistics, which looks at how language structures meaning. However, the field of semiotics had a broader set of goals: it sought to explore how both linguistic and image-based forms of communication shaped larger social and cultural structures.

Why photography and text, and not a painting or a sculpture? Kosuth’s avoidance of the traditional media was also a critique of the ways that art institutions had historically accepted and promoted only certain types of artworks. This criticality had roots in the radical Dada practices of Marcel Duchamp and other early twentieth-century artists who pushed for the acceptance of new forms of art. Artists from the 1960s onward were increasingly interested in building on this legacy, challenging the ways that museums, academies, and other art institutions adhered to traditional, nineteenth-century notions of what art was and should be.

The viewer’s role

When we look at One and Three Chairs, we are not drawn to admire its beauty, nor are we presented with a relatable story or a figure to be admired. Rather, we are invited to consider the concept of what a “chair” is, as well as the nature of visual and linguistic representation itself—fundamental questions that Plato asked more than two thousand years ago. And like the ancient Greek philosopher, Kosuth focuses on the idea of a “chair,” rather than simply its physical representation. But he also reveals the importance of the viewer’s role in the function of conceptual artwork. It is not until we approach pieces such as One and Three Chairs and begin to engage with them intellectually that the actual “artworks”—the concepts—emerge. In this sense, conceptual art can only exist in tandem with its audience, and is created anew each time we view it. This emphasis on the participation of the viewer was also important for the related movements of performance and participatory art, which gained momentum as well beginning in the 1960s.

One and Three Chairs stripped art of its outer casing and celebrated, instead, the importance of the conceptual for both the artist and the viewer. Importantly, it also stripped the artist of his or her role as a romantic and existential agent of personal expression (an aspect of art that was increasingly important from the nineteenth to the mid-twentieth century). The conceptual artist appears, instead, as a philosopher questioning the nature of reality and the social world in which art and audience reside.