The central figure seems to shout in Hu Yichuan’s image, To the Front!, as he urgently calls for unity and defense. A crowd appears to rush past awkwardly angled city walls. This arresting image responded to Japan’s invasion of China, inciting the indignation of the Chinese public and hardening their resolve to resist Japanese aggression. Since the May Fourth Movement of 1919, when students demonstrated in protest against the stipulations of the Treaty of Versailles, many artists looked to the visual arts for strengthening the nation. Not long after, the Chinese Communist Party formed in Shanghai, and many young Communist artists and writers joined art societies, hosted art exhibitions, and studied woodcut prints from China and Europe. As a woodcut print, To the Front! represents one of many images widely circulated in efforts to foment resistance against the Japanese invaders and to denounce the inaction of those in power.

A visual rallying cry

Hu Yichuan and his fellow woodcut artists responded to the Japanese invasion of Manchuria and bombing of Shanghai in 1931 with images that were militant and intended to function as a visual rallying cry for the Chinese people. Characteristic of woodcut prints, To the Front! is startlingly simple, composed only of dramatic slashes of contrasting black and white that reveal the terse movements of the artist’s chisel. The image is deliberately flattened to lend an unsettling sense of drama and confusion. The figure in the foreground fills nearly the entire frame, his right arm extended with a hand open as if gesturing to the crowd, underscoring the subject’s desperate cry to arms.

Conveying anger and urgency, Hu’s image met a critical moment in Chinese history. After the fall of the last imperial dynasty in 1912, the Chinese Nationalist Party (Guomindang 國民黨, GMD or KMT) established the Republic of China in the city of Nanjing. However, the Nationalists struggled to establish a new government while facing the threat of imperial Japan.

Japanese aggressions began with the Manchurian Incident in 1931, when rogue Japanese military personnel staged an explosion along the train tracks carrying the Japanese army. Blaming the incident on Chinese dissidents, the Japanese army then invaded Manchuria in response and began bombing the city of Shanghai in August of 1931. As the horrors of war mounted, many—especially members of the Chinese Communist Party (Gongchandang 共产党, CCP)—felt that the Republican Nationalists were not doing enough to protect the nation.

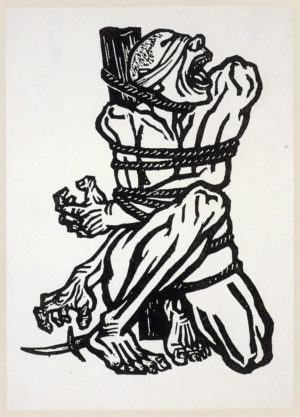

Like Hu, who was active in woodcut art societies and exhibitions, the artist Li Hua echoed Hu’s revolutionary sentiments in China, Roar! Similarly inspired by China’s helplessness in the face of Japanese aggressions, Li personified the nation as a rugged, well-muscled youth, a member of the masses. Bound and blindfolded, the figure appears to be roaring with rage as he gropes for a knife to free himself. The boldness and simplicity get the work’s message across loudly, drawing attention to social injustice and offering a call to arms to fight against Japanese oppression.

The modern woodcut movement

Käthe Kollwitz, Memorial Sheet of Karl Liebknecht (Gedenkblatt für Karl Liebknecht), 1919–20, woodcut heightened with white and black ink, 37.1 × 51.9 cm (photo: Anvilaquarius)

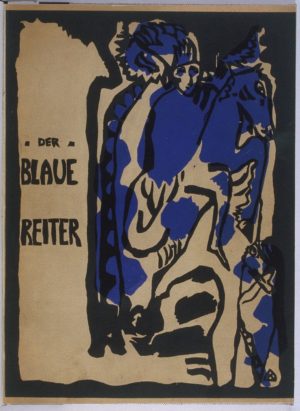

The modern woodcut movement (Xinxing banhua yundong 新兴版画运动) began in China with the early Communist writer, Lu Xun, who promoted woodblock prints as tools of political propaganda. Having amassed a large collection of European woodblock prints, Lu took particular interest in those with social and political messages such as artists like Käthe Kollwitz, whose interest in the suffering of the masses can be seen in her woodcut print, Memorial Sheet of Karl Liebknecht.

Sympathetic to the emerging left-wing communist movements, Lu believed that while the Nationalists had begun the revolution, their socialist agenda did not go far enough. Lu thought that the answer to sufficient Chinese reform lay in Communism. He made his growing collection of European, Soviet, and Japanese woodcuts available to young artists for study.

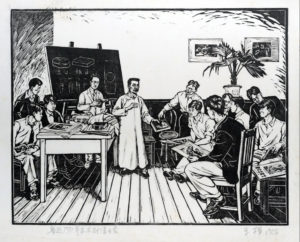

Li Hua, Lu Xun and Uchiyama Kakechi Conduct a Woodcut Class in Shanghai, 1931, woodcut print on paper

Ming banknote, 1375, Ming Dynasty, China, paper, 34 x 21.8 cm (© Trustees of the British Museum)

In August 1931, Lu invited thirteen art students to study printmaking techniques with the Japanese engraver Uchiyama Kakichi in Shanghai. While Sino-Japanese artistic exchange might seem odd in light of anti-Japanese sentiments, it reflected the close relationship of the two nations before Japan’s invasion and challenge to Chinese sovereignty. Although other artists had been working in woodcuts, most notably Li Shutong who was among the first to study in Japan, Lu’s printmaking workshop is recognized today as the foundation of the modern woodcut movement. Woodcut artists formed societies, exhibited their works, and printed them in journals in efforts to expand the role of art in society.

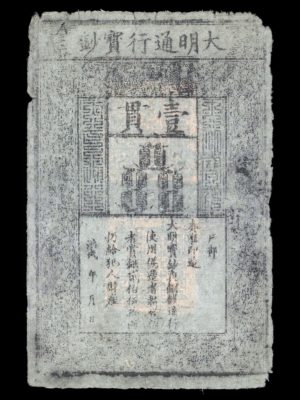

The woodcut medium existed since at least the ninth century in China, and its long history was a major draw for the early twentieth-century Communist artists. Woodcuts are carved wooden stamps that can be reused; in other words, they can be “stamped” over and over. They typically employ only black and white for clarity in message and emotional intensity. As the earliest paper currency in the world and a medium used for public announcements, print encyclopedias and classics, and religious imagery, the woodcut print is inseparable from Chinese visual culture and its history.

Like other prints of the early twentieth century, To the Front! also may be described as a hybrid art informed by traditional Chinese, Japanese, and European media, styles, and messages. Early twentieth-century Chinese woodcuts drew heavily on the style of European woodcuts, as well as modernist oil painting, with sources ranging among German Expressionism, Russian Constructivism, and British Art Nouveau.

Departing from the Chinese medium of water-based ink, artists used oil-based paint in the prints to highlight their modern and foreign nature. Twentieth-century woodcuts also differed from earlier woodblock production methods, as well as those of Japanese prints, in that early Communist artists not only designed the images, but also carved the blocks themselves. Previously, artists would design the image, but a skilled craftsperson would carve the blocks. This new approach—with the artist designing, carving, printing each image—actually marked a departure from the mechanized, reproductive technologies of their modern moment. Rather than upholding traditional social class distinctions between artists and craftspeople, these young woodcut artists demonstrated a process that aligned more closely with their political ideals.

Hu Yichuan, To the Front! (detail), 1932, woodcut, 1932, 9 1/8 x 12 inches (Lu Xun Memorial, Shanghai)

“Modern art must follow a new road . . .”

In 1932, Lu Xun viewed Hu’s To the Front! in an exhibition of over a hundred works held at the Shanghai YMCA. He reportedly purchased ten prints (possibly even this one), and viewed Chinese works in various media as well as German prints. Although the Shanghai YMCA hosted many lectures and exhibitions since its construction in 1931, this exhibition was the work of an art society called the Spring Earth Art Research Center, a group of leftist artists, writers, and poets (such clubs frequently changed names of their group to avoid persecution). Their manifesto stated:

Modern art must follow a new road, must serve a new society, must become a powerful tool for educating the masses, informing the masses, and organizing the masses. This new art must accept this mission as it moves forward! [1]

Circulated among avant-garde artists at exhibitions and printed in popular illustrated presses, Chinese woodcuts in the early twentieth century are an example of an art form intended as a rallying cry—a visual call to arms. Only a few years later in 1937, China descended into the Second Sino-Japanese War, known in Chinese as the “War of Resistance against Japanese Aggression,” marking the beginning of World War II in Asia.

Notes:

[1] Translation from Julia F. Andrews and Shen Kuiyi, “The Modern Woodcut Movement,” in A Century in Crisis: Modernity and Tradition in the Art of Twentieth-Century China, edited by Julia F. Andrews and Shen Kuiyi (New York: The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, 1998), p. 216.

Additional resources

Julia F. Andrews and Shen Kuiyi, “The Modern Woodcut Movement,” in A Century in Crisis: Modernity and Tradition in the Art of Twentieth-Century China, edited by Julia F. Andrews and Shen Kuiyi (New York: The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, 1998).