Camel, first half of the 12th century, fresco transferred to canvas, from San Baudelio de Berlanga, Spain (Met Cloisters, New York)

[0:00] [music]

Dr. Lauren Kilroy-Ewbank: [0:06] We are standing here in the Cloisters Museum in New York City, looking at a fresco painting of a camel that has been transferred to canvas.

Dr. Steven Zucker: [0:15] Originally, this would have existed as part of the wall in a hermitage, that is, in a religious community in Spain in Castile-León.

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [0:22] This actually comes from San Baudelio de Berlanga, which is halfway between Madrid and Zaragoza, and it dates to the 12th century, even though the space from which it comes was built a century earlier.

Dr. Zucker: [0:35] This was part of a frieze — that is, a band of painted animals and hunting scenes — that existed originally below additional images of the life of Christ. If you were to walk into this room originally, you would have been confronted with lots of imagery. Religious imagery above, and more secular, more playful imagery below.

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [0:54] In a Christian space like San Baudelio de Berlanga, you would expect to see scenes like the life of Christ. What is unexpected is that the scenes of animals and hunting scenes, like the camel we’re seeing here, were much larger than the scenes of the life of Christ and closer to eye level. So what are they doing in a Christian space?

Dr. Zucker: [1:15] Well, unsurprisingly, there’s symbolic value. These animals mean things.

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [1:19] The location of this religious space is important for why we’re seeing things like this camel here. In 711, you have the conquest of much of Spain by the Umayyads.

Dr. Zucker: [1:32] Now, the Umayyads was a ruling caliphate. That is, inheritors of Muhammad’s religious leadership over Islam. However, the Umayyads were basically run out of town and escaped to Spain, where they reestablished their caliphate.

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [1:44] In the 8th century, you have the beginning of what’s called the Spanish Reconquest, which was Christians attempting to reconquer the Iberian Peninsula from Muslims. By the 11th century and the 12th century, many more of those territories had been reconquered by Christians. The space from which this fresco comes was in a frontier zone.

Dr. Zucker: [2:04] A contested space at the edge of Christendom and Al-Andalus — that is, the area that was controlled by Islam.

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [2:11] In the 12th century, when these frescoes were commissioned, it was right around the time when King Alfonso here in this area had taken back control of some of the surrounding area. For a long time, this area had been under Muslim control or had a heavy influence from Islamic culture.

Dr. Zucker: [2:29] The camel will remind anybody in Spain of the Holy Land, of the Eastern Mediterranean. It is an interesting, complicated mix because the camel then represents both the origins of Christianity but also a land that is now controlled by Islam.

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [2:43] This camel was accompanied by other animals that don’t necessarily have any scriptural basis or hunting scenes that we don’t expect to find inside a Christian space.

[2:53] Another way we could read this camel is in relation to Islamic luxury arts, things like ivory caskets or metalwork, where you do find animals like this one.

[3:04] Even above the camel we see lions that almost look like griffins in these roundels that are similar to what we find on some of these Islamic luxury goods.

Dr. Zucker: [3:15] I love this camel. I love that he’s giving us a bit of a side eye. I love the heavy outline that gives him such a playful quality, that wonderful swoop of the neck and the careful rendering of the hooves.

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [3:26] Camels signified wealth, and so displaying it here, perhaps the artist who is painting this inside of a Christian space wanted to convey some of that idea of luxury and wealth, both the camel itself and its associations with the Eastern Mediterranean, but also that we do find camels on Islamic luxury goods.

Dr. Zucker: [3:46] It’s important to remember that the artist probably never saw an actual camel, and so this would have been copied from one of those luxury items. You can see a little bit of confusion around the hump area. There’s that larger hump and then there seems to be smaller hump within it.

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [4:00] One of the things that I find so interesting about this fresco is that it really speaks to some of the tensions, the ambivalences, but also the shared cultural practices that we find in Spain throughout the Middle Ages and eventually into the Renaissance.

[4:12] [music]

Introduction

The Romanesque hermitage of San Baudelio de Berlanga was built in the eleventh century in the border zone of Islamic and Christian territories in what is today Spain. While it may seem isolated today, in the eleventh century it was situated on an old Roman road that came from southern France that bustled with activity. It brought merchants as well as pilgrims going to visit the relics of the early Christian martyr St. Baudilus in Nîmes. The hermitage’s architectural style is often called mozarabic, a term used to describe Christians living under Muslim rule and who drew from Arabic visual culture.

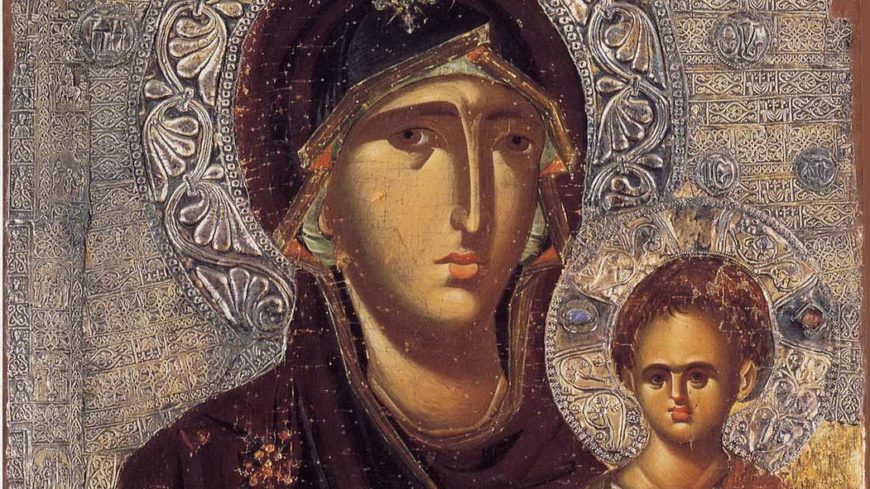

More than a century later, the building’s interior was transformed with the addition of brightly painted frescoes. In the upper levels are scenes from the life of Christ. Below, and painted on a larger scale, are more secular scenes of animals, hunting, and illusionistic silk tapestries. Among the animals depicted is a camel seen in profile. The animals suggest the complex history of medieval Spain, because they are based on animals seen on Islamic luxury goods (such as ivories, metal objects, ceramics, and textiles).

Construction of the hermitage and the painting of the murals occurred during an important moment in medieval Spain, one which saw boundaries shifting between faiths and rulers. Since 711, much of the Iberian Peninsula (today, Portugal and Spain), had been ruled by the Umayyad caliphate. The Umayyads were heirs to Muhammad, who had initiated the spread of the faith of Islam in the 6th century. The Umayyads created a vast empire that spanned much of the eastern and southern Mediterranean world, and eventually they reached the Iberian Peninsula (Spain and Portugal) in 711. After seven years, they had conquered much of it from the Christian Visigoths. These new Muslim territories were called al-Andalus. Then, in 750, the Umayyads were supplanted by the Abbasids. The last ruler of the Umayyads fled to al-Andalus, creating a new dynasty there with Córdoba as its capital. It was called the caliphate of Cordoba. Al-Andalus would develop rich, complex artistic traditions—the result of a diverse population that included Christians, Jews, and Muslims.

Still, Christians would try to regain lost territories and acquire others across the Iberian Peninsula after 711, in what has been called the Spanish Reconquest (although this term is considered problematic). The ensuing centuries would mean that the borders between al-Andalus and Christian-ruled Iberia would frequently change. San Baudelio de Berlanga was initially built in a frontier zone, and then when it was painted in Christian-controlled kingdom. A sign that Christians were gaining ground in acquiring territories came in 1085, when King Alfonso VI conquered the important city of Toledo.

Umayyad rule ended in 1031 after Christian forces were finally able to defeat the powerful caliphate. What remained of southern Al-Andalus would be divided into taifas (independent principalities). (Despite the downfall of the Umayyads, other Muslim rulers would establish themselves on the Iberian Peninsula until 1492). Still, the murals—which would have been painted when the hermitage was more associated with a Christian kingdom—-demonstrate that artists continued to draw on Islamic courtly arts. It was part of the complex, rich cultural heritage of the Iberian Peninsula.

Today, most of the hermitage’s murals are not in their original location, but were removed from the walls in the 1920s, mounted onto canvas, and acquired by different museums, including the Prado (Madrid), Cloisters (NYC), the Indianapolis Museum of Art, and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Terms and key ideas

- Al-Andalus, the Umayyads, and Islamic art in Spain

- Spanish “Reconquest”

- Romanesque murals

- Frontier zone

- Sacred and secular art

Test yourself with a quiz!