Scuola grande di S. Marco e chiesa SS. Giovanni e Paolo, Venice, photo: Mark Edward Smith, by permission © Mark Edward Smith

Venetian Society and the scuole

The Republic of Venice lasted for almost one thousand years (from the eighth to the eighteenth century). Its exceptional stability was due not only to its geographical position (in the middle of a protective lagoon) and its effective political system, but also to its social structure and the stabilizing presence of the scuole.

The scuole were confraternities, or brotherhoods, founded as devotional (religious) institutions, that were set up with the purpose of providing mutual assistance. They provided an important guarantee against poverty and played a crucial role in protecting individuals and families in need. The scuole were supported by a tax levied on each member and on the bequests of wealthy brothers. These donations and earnings were then used to help all the members and their families. The scuole also depended on the state, which exercised a protective and supervisory role. Each scuola had a patron saint and a statute with its own symbols and emblems.

In the fifteenth century, more than two hundred such scuole existed, among which six were scuole grandi (large scuole). By then the initial religious role had shifted to a more civic purpose. The scuole grandi included individuals who had diverse occupations and could afford spectacular meeting-houses, while the scuole piccole (small scuole), could be purely corporate. Even foreigners, in order to overcome the lack of protection by the State, and to strengthen their national or religious identity, founded several scuole piccole. These were all dissolved (but one) with the Napoleonic invasion in 1797—the year that marked the end of the Venetian Republic.

Scuola di San Giorgio degli Schiavoni (with paintings by Vittore Carpaccio), Venice, photo: Mark Edward Smith, by permission © Mark Edward Smith

Social structure

In Venice there were three distinct social classes:

Patricians

The patricians were drawn from the nobility and were the ruling class. They represented about 5 percent of the population and were the only ones eligible to hold positions at a high political level.

Citizens

The next 5 percent were known as citizens. Citizens were divided into two categories: those who were Venetian by birth and those who became citizens after a lengthy process of naturalization (similar to green card status in the United States). Professionals, employees of the bureaucracy and merchants usually qualified as citizens. Though Citizens did not hold political power, they could exert some influence through the scuole, where the most distinguished members held significant positions.

Working class

The working class included artisans, small traders, other workers, and seamen. These people were not necessarily poor, just as the patricians were not necessarily rich. The working class also had their own scuole.

The Teleri

The scuole served an important role in the patronage of Venetian art. Along with altarpieces, they commissioned large narrative painting cycles (teleri). The subject matter of the teleri (telero — singular) was always religious but they also carried secular and civic connotations. The charm of these large paintings lies in the fact that they tell stories that unfold step by step. Because the imagination of the artists and their narrative skill was combined with their patron’s instructions—and there are even instances when members of a scuola required they were included in the paintings, teleri provide a fascinating visual journey that allows us to appreciate and understand Renaissance Venice. What follows are a few outstanding examples with brief descriptions.

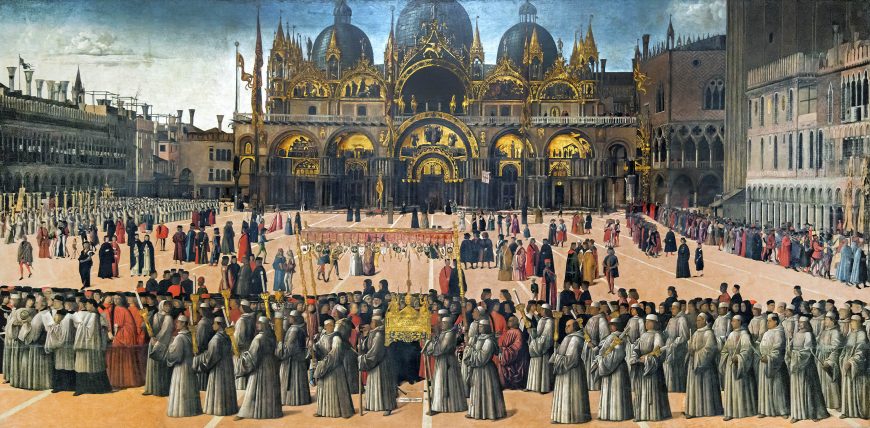

Gentile Bellini, Procession in St Mark’s Square, 1496, tempera on canvas, 347 x 770 cm (Gallerie dell’Accademia, Venice)

Gentile Bellini, Procession in St Mark’s Square, 1496

The Scuola Grande di San Giovanni Evangelista (a large scuola dedicated to St. John the Evangelist) commissioned paintings that narrate the miracles made by the relic of the True Cross that was in its possession. This sacred fragment was carried through the streets of the city each year on April 25 for the feast of St. Mark (patron saint of the city). In Venice, processions had great civic and religious meaning; creating continuity season after season, virtually unchanged over time.

This painting, by the Venetian artist Gentile Bellini, depicts a miracle. In the midst of the procession, in the foreground, is a man in prayer. He is a merchant from Brescia who, having arrived in Venice for business, received the terrible news that his beloved son was in critical condition from a blow to his head. The next day, the man, aware of the powers of the True Cross, went to attend the ceremony, and when the famous relic passed in front of him, he knelt before it as a sign of devotion. When he returned home, he found his child miraculously healed.

The protagonists of the procession are in the foreground: the scuola’s brothers (members) are dressed in white; the procurators (the office of procurator of St Mark’s was the second most prestigious appointment in the Venetian government after that of Doge) and senators of the Republic wear red gowns. The patricians and the citizens wear black. The members of the scuola carry a canopy to protect the reliquary that holds the sacred relic as it is carried through St. Mark’s Square (the religious and political heart of the city).

Reliquary (detail), Gentile Bellini, Procession in St Mark’s Square, 1496, tempera on canvas, 347 x 770 cm (Gallerie dell’Accademia, Venice)

St. Mark’s Square is reproduced in Bellini’s painting with a wide-angle view in striking detail, providing a remarkable visual document of the square at the end of the fifteenth century. To open up the scene, the artist moved the bell tower to the right. St. Mark’s Basilica, sparkling with its Byzantine gold (gold also lights up the reliquary in the foreground), functions as a backdrop. The square is populated by a cosmopolitan mix of people elegantly dressed in the fashion of the time: some young people in multicolored stockings, a group of Jews, a number of Turks wearing turbans, as well as merchants and children. On the left, women look out from the windows and colorful carpets are displayed from balconies as a sign of celebration.

Vittore Carpaccio, The Healing of the Madman, 1496, tempera on canvas, 365 x 389 cm (Gallerie dell’Accademia, Venice)

Vittore Carpaccio, The Healing of the Madman, 1496

Carpaccio portrayed another miracle of the True Cross for the Scuola Grande di San Giovanni Evangelista. The artist presents the passage of the miracle from the procession on the bridge (whose members are in white) to the main event that takes place in the Patriarch of Grado’s palace on the upper left. The Patriarch is seen raising the relic before a possessed man who fixes a glassy-eyed stare on it, and who will be miraculously cured. The miracle is in progress, a dramatic moment made even more authentic by the fact that the scene takes place in a marginal position within the composition. The white tunics of the procession members surround the scene, while all around life unfolds quietly, and it seems that few are aware of what is happening. Here Venice itself is not just the background but a dominant theme of the painting.

One can see the Rialto Bridge (the financial heart of the city) as it was then, constructed in wood, with a row of shops on each side, while below the Grand Canal (the main waterway of the city) is animated by gondolas and their gondoliers. In the distance, among the colorful palaces and the characteristic chimneys, daily life is in full swing. A woman beats a carpet, another hangs the laundry, a mason fixes a roof. In the lower section several men in turbans confirm the diversity of those who visited the Rialto market.

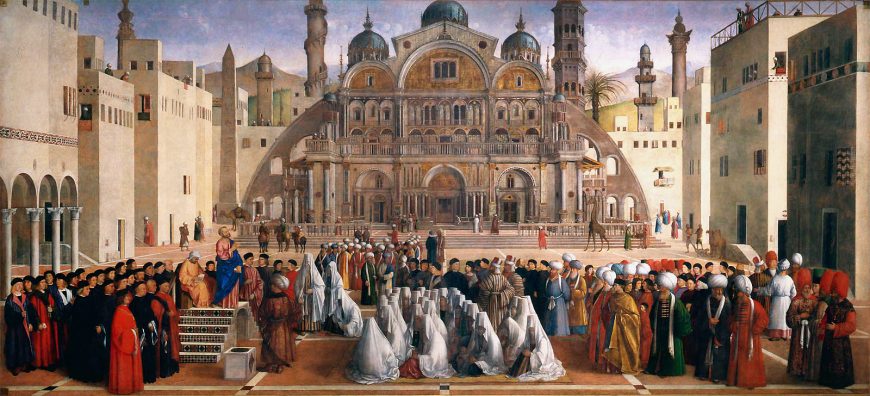

Gentile Bellini and Giovanni Bellini, Saint Mark Preaching in a Square of Alexandria in Egypt, 1504-07, oil on canvas, 347 x 770 cm (Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan)

Gentile Bellini, St Mark Preaching in Alexandria, Egypt, 1504-07

The Scuola Grande di San Marco commissioned Gentile Bellini to paint St. Mark Preaching in Alexandria, Egypt, but the artist died before the painting was completed, so it was finished by his brother Giovanni Bellini (who, like Gentile, had never been to Alexandria). For the costumes and architectural details, Gentile drew inspiration from his stay in Constantinople and from travelers’ accounts. The layout of the painting is reminiscent of Procession in St. Mark’s Square, where the figures in the foreground are represented in profile.

Saint Mark (detail), Gentile Bellini and Giovanni Bellini, Saint Mark Preaching in a Square of Alexandria in Egypt, 1504-07, oil on canvas, 347 x 770 cm, (Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan)

The saint, who will become the patron saint of Venice, preaches from a small podium placed between the scuola brothers and the Arabs, while in the background stands a great temple whose façade, divided into three parts, brings to mind the meeting house of the Scuola Grande di San Marco, the Basilica of San Mark and the Hagia Sophia in Constantinople. Nearby is an obelisk engraved with hieroglyphics and several minarets. In the square, alongside the inhabitants, a number of exotic animals stroll by, including camels and giraffes.

Vittore Carpaccio, Arrival of the Ambassadors from the Saint Ursula cycle, 1490-96, tempera on canvas, 278 x 589 cm (Gallerie dell’Accademia, Venice) (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Vittore Carpaccio, Arrival of the Ambassadors, 1490-96

At the end of the fifteenth century, Vittore Carpaccio was commissioned by the Scuola Piccola di Sant’Orsola (a small scuola dedicated to Saint Ursula) to paint a cycle of nine paintings on the Life of Saint Ursula, taken from the popular medieval book, the Golden Legend by Jacopo da Varagine. With his vivid imagination he had no difficulty creating a northern scene (Brittany and Germany) set in the fourth century, often with elements drawn from an imaginary city reminiscent of fifteenth-century Venice. In the story, the ambassadors approached the father of Ursula in Brittany asking for the hand of his daughter on behalf of the English prince Ereo. After consulting her father, the girl accepted, on the condition that Ereo be baptized at the end of a long pilgrimage to Rome. After the baptism, on the way back to Cologne, the married couple ran into the king of the Huns who fell in love with Ursula. She rejected the proposals of the bloodthirsty ruler, preferring death instead.

The story begins with the Arrival of the English Ambassadors, where we see a large room represented with no front walls, while in the background we see buildings in the Venetian style and details of city life. Carpaccio skillfully employs perspective while maintaining the frieze-like structure typical of Venetian narrative paintings. The telero includes two consecutive moments. The first episode displays the ambassadors approaching the king; this scene unfolds behind a railing left accessible by an open gate. The following episode takes place in Ursula’s bedroom where she receives the message from her father. The room is simple but includes a devotional painting testifying to the pious character of the young girl.

Vittore Carpaccio, Saint George and the Dragon from the cycle: Episodes from the Life of Saints Jerome, George and Triphun, 1502, tempera on canvas, 141 x 360 cm (Scuola di San Giorgio degli Schiavoni, Venice)

Vittore Carpaccio, Saint George and the Dragon, 1502

Carpaccio was also summoned by the Scuola di San Giorgio degli Schiavoni (Dalmatians) to depict the cycles of Saint George and Saint Jerome, still in-situ today. The cycle of Saint George is also taken from the Golden Legend. In the narrative, Selene, a city in Libya, was oppressed by a terrible dragon that fed off the meat of boys and girls and terrorized the town with threats of death and destruction. When it was the king’s daughter’s turn to be devoured, Saint George, on his steed, intervened swiftly, injured the dragon and then led it into the town before killing it in front of everyone. Thanks to the surprising liberation from the dragon, the knight persuaded the king and his people to be baptized.

In the combat scene with the dragon, the background is delineated to the left by a city, represented by several minarets, an obelisk, an equestrian statue, exotic palm trees and a castle typical of the Veneto (the region in northern Italy that was ruled by the city of Venice). On the other side we see the African princess, with a fair complexion and elegantly dressed in European-style clothing, looking on calmly, with her hands folded. In the foreground, the scene runs along the diagonal of the lance of Saint George who struggles valiantly with the dragon on a ground strewn with the remains of tortured bodies.

Conclusion

The complex narratives depicted in these paintings represent important religious events and miracles—yet directly or indirectly, they are simultaneously preoccupied with the complexity, diversity, and beauty of Renaissance Venice. They also point us to the critical role played by the scuole in both the life and art in the Most Sererene Republic of Venice.

Additional resources

Patricia Fortini Brown, Venetian Narrative Painting in the Age of Carpaccio (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998).

Augusto Gentili, Le storie di Carpaccio (Venice: Marsilio,1996).

Peter Humfrey, Painting in Renaissance Venice (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995).

Brian Pullan, Rich and Poor in Renaissance Venice: The Social Institutions of a Catholic State to 1620 (Oxford, 1971).

Brian Pullan, “The Scuole Grandi of Venice: Some Further Thoughts,” in Christianity and the Renaissance: Image and Religious Imagination in the Quattrocento, ed. T. Verdon and J.

Scuola di San Giorgio degli Schiavoni

Lorenza Smith, Venice: Art and History (Verona: Arsenale, 2011).