Gallery in the Alte Pinakothek, Munich (photo: Dr. Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

When people think of museums, art museums most often come to mind—solemn places where visitors stand in silence contemplating neat rows of paintings. The exploratory, hands-on science center, the contextualized ethnographic collection (think dioramas), and the storytelling of history museums seem worlds away. But all museums have a history to tell. Museums are more than containers of things; rather, they are complex reflections of the cultures that produced them, including their politics, social structures, and systems of thought.

The word “museum” comes from the nine Muses, the classical Greek goddesses of inspiration, though the famed “Museion” of ancient Alexandria was more like a university, with an important library, than a place for the display of objects. While scholars generally place the earliest museum (in the sense that we understand it today) in 17th or 18th-century Europe, there were earlier collections of objects and sites of display, including the public squares or fora of ancient Rome (where statuary and war booty were exhibited), medieval church treasuries (for sacred and valuable objects), and traditional Japanese shrines where small paintings (ema, traditionally of horses) were hung to draw good favor.

Relief panel showing The Spoils of Jerusalem being brought into Rome after 81 C.E., marble, 7 feet, 10 inches high on the Arch of Titus, in the Roman Forum, erected by Emperor Domitian after the death of his brother Titus in 81 C.E., commemorating the capture of Jerusalem by Titus in 70 C.E. (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The modern museum, as a secular space for public engagement and instruction through the presentation of objects, is tightly bound to several institutions that arose simultaneously in 18th and 19th-century Europe: nationalism fused with colonial expansion; democracy; and the Enlightenment. Thus this historical essay and several others in this series on museums focus largely on Europe and North America. The influence of the museum model, as a tool of colonialism but also as a site for local adaptation and self-definition in places other than the West, are two sides of an important coin that is just beginning to receive attention from art historians.

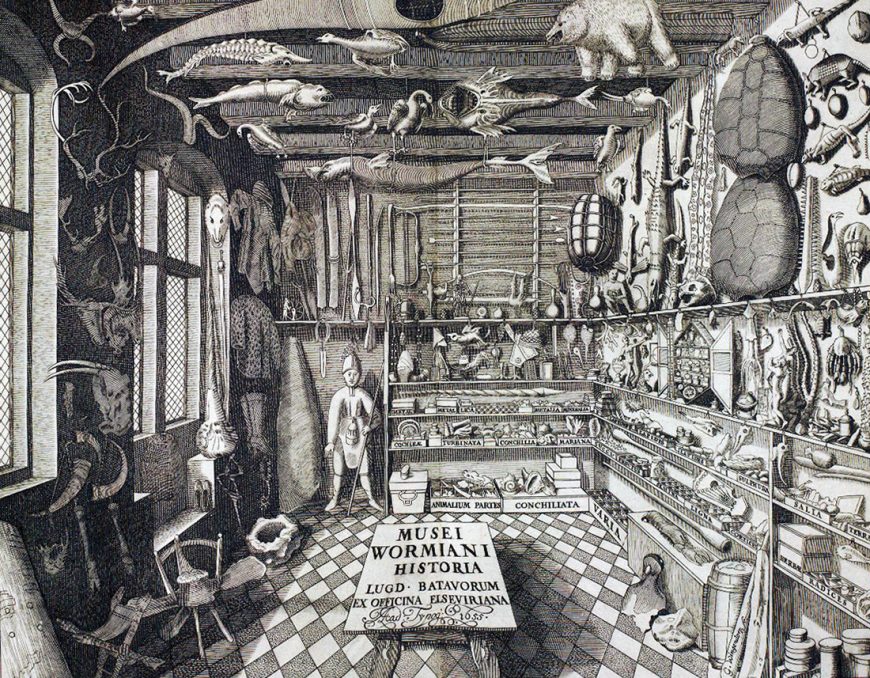

Wunderkammern

The nearest thing to a museum in early modern Europe were the Wunderkammern, or cabinets of wonders, assembled by curious nobles, wealthy merchants, and scholars. Emerging just as Europe was extending its reach into “new” continents and cultures, Wunderkammern were places to gather together, interpret, and show off the riches of the world. Some were literal cabinets, fitted with cupboards and drawers; others were rooms stuffed with animal, mineral, vegetal, and artistic treasures. Much like our museums—and differently from church treasuries and displays of war booty—Wunderkammern were intended to deepen people’s knowledge through the presentation of things.

Frontispiece depicting Ole Worm’s cabinet of curiosities, from Museum Wormianum, 1655 (Smithsonian Libraries). Ole Worm was a Danish physician and natural historian. Engravings of his collection were published in a volume after his death.

Display cabinet from Augsburg, Germany, c. 1630, ebony and other woods, porphyry, gemstones, marble, pewter, ivory, bone, tortoiseshell, enamel, mirror glass, brass, and painted stone, 73 x 57.9 x 59.1 cm (The J. Paul Getty Museum)

In most other ways, however, Wunderkammern differed from modern museums. They were the domains of the wealthy elite, typically located in a private palace and open only to the collector, his immediate circle, and the occasional visitor who was properly furnished with a letter of introduction. This intimacy meant that objects could be taken from shelves, handled, juxtaposed, and discussed before being returned to storage, often out of sight. Wunderkammern were more like private study collections than the art museums most of us know today.

As is true of all museums, the organization of the Wunderkammern mirrored the intellectual outlook of their day. “Wonders”— extraordinary objects like featherwork from New Spain or a spiraled unicorn horn (actually the tusk of a narwhal)—were among the most valued, as marvelous expressions of creation. At the same time, Wunderkammern were all-encompassing, ideally including every kind of object, both natural and artificial (i.e. made by human hands) from every corner of the world.

The studiolo of Francesco I in the Palazzo Vecchio, Florence. Though it is empty now except for the paintings on the walls and ceiling, it originally contained Francesco I’s collection of rare objects. (Photo: Web Gallery of Art, CC 0)

Wunderkammern were seen as “microcosms” of God’s creation: the cosmos, Greek for “universe,” was encapsulated in one, miniaturized reflection of its literal awesomeness. This was an age of rising scientific interest, but this interest was still thickly wrapped in religious covers. In the worldview of elite European collectors, all elements of the cosmos were interconnected in a perfectly balanced web of meaning. If one laid out a Wunderkammer in imitation of this divine plan, the plan would be revealed. Francesco I de’ Medici of Florence, for example, probably arranged his collection according to the four Aristotelian elements: earth, air, fire, and water. Objects as varied as armor, mirrors, and enamels were linked as fire-objects (since they were created using heat), pearls and narcotics (typically diluted for use) as water-objects, and so forth. Other Wunderkammern had other organizational systems, but they were typically rooted in visual or conceptual resemblance (e.g. fire=forge=armor).

Robert Smirke, south portico of the British Museum, 1846-47 (photo: Ham, CC BY-SA 3.0)

The British Museum and the Enlightenment

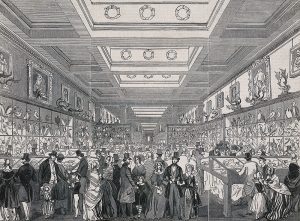

The Zoological Gallery in the British Museum, c. 1845, engraving (The Wellcome Collection, CC BY 4.0)

Toward the middle of the eighteenth century a different structure emerged, one associated with several important trends. One of these was the rise of the Enlightenment. This intellectual movement aimed to make sense of a world that— from the perspective of Europeans who were colonizing other places around the globe—was revealing new things that demanded new explanations. Enlightenment thinkers relied on the emerging tools of secular empiricism, or sense-based evidence, and proof through repetition—that is, the guiding concepts that lie at the root of modern science.

Richard Westmacott, The Progress of Civilization, pediment of the south portico of the British Museum, 1850s (photo: Matt Lancashire, CC BY-NC 2.0)

The British Museum embodies the ideals of the Enlightenment. Founded in 1750 as a gift to the British nation by Sir Hans Sloane, its core collection consists of specimens he acquired as a medical doctor in the West Indian colonies (plants, birds, and seashells, for example) and objects he purchased from other explorers (including ethnographic and archaeological objects and manuscripts). These were eventually housed in an imposing building that featured an image of Britannia, the personification of the British Empire, at the apex of its great triangular pediment. This architectural reference to classical temples was intentional, symbolizing a space of protection and prestige, and the nationalist imagery above its entrance made it clear just who controlled the materials within—much of it from the colonies.

The British Museum inherited the all-inclusive approach to collecting characteristic of the Wunderkammern, though it focused on typical objects, or specimens, as much as exceptional ones. Not for nothing are the British Museum and its kin termed “encyclopedic” (encyclopedias were another product of the 18th century). Rather than mirroring the balanced, interwoven web of the divine microcosm, however, the new sciences emphasized differentiation and development as tools for an empirical understanding of the universe.

View of the Campidoglio, Rome, with the Capitoline Museum at top right, 1750, print, 32 x 41 cm (Bibliothèque nationale de France)

The rise of museums

Museums reflected and helped shape that outlook. The Enlightenment is when we begin to see specialized collections, including museums devoted only to art—the Capitoline (Rome, 1734), the Louvre (Paris, 1793), and the Alte Pinakothek (Munich, 1836). Similarly, dedicated collections of plants (botanical gardens), animals (zoological gardens), and eventually natural history and ethnographic objects emerged. One key thing these collections shared was a scheme of linear, didactic layouts dedicated to narratives of development or progress.

View through the Egyptian Room in the Townley Gallery at the British Museum, 1820, watercolor, 36.1 x 44.3 cm (The British Museum).

In art museums, this meant chronological arrangements subdivided by nation, local school, and artist and based in the comparison of visual forms: for instance, the idea that ancient art leads to the Renaissance, which leads to French Neoclassisicm, or that Egyptian art was less “developed” than Greek art. Using different examples, this same history of art could be repeated in different places, much like a scientific demonstration or a proof. A similar general narrative continues to define many art museums today.

The Brooklyn Museum, c. 1905, dry plate negative, 8 x 10 inches (The Library of Congress). Founded in 1895, building designed by McKim, Mead, & White.

The “white cube”

In the newly formed United States, art museums were an unimagined luxury until the later decades of the nineteenth century, when wealthy patrons in rapidly expanding American cities began to emulate European models. This is why so many historic American museums resemble their European counterparts (temple-fronted facades over a grand staircase), echo their collecting habits (classical sculpture, Renaissance painting, etc.), and mimic their approach to layout and installation.

Yet it was in the United States that some of the most influential trends in modern art museums also emerged. One of these is the “white cube” approach which, despite precedents in Europe, was most fully exploited at The Museum of Modern Art in New York City in the 1930s under the direction of Alfred H. Barr. By minimizing visual distractions, Barr hoped to direct viewers toward a pure experience of the art work. The bare spaces, white walls, and minimalist frames he used are now so common that we hardly notice them.

Installation view of Modern Works of Art: 5th Anniversary Exhibition, MoMA, November 19, 1934–January 20, 1935 (The Museum of Modern Art)

The “white cube” was rooted in a philosophy that aimed to liberate art and artists from the conservative forces of history. Ironically, this model has taken over, and art museums from Rio to Abu Dhabi to Shanghai draw on similar exhibition tactics. This has led some museum critics to wonder if the “white cube” has itself become a vehicle of cultural control.

Another less recognized pioneer, but one receiving renewed attention, is John Cotton Dana, founder of the Newark Museum in Newark, New Jersey (1907). Dana rejected what he called the “made-to-order museum,” that is, a museum that simply replicated European models. He believed collections should serve local audiences, responding to their needs and wants. Today many art museums are following Dana’s philosophical lead, developing collections that reflect the ethnic make-up of the communities they serve and striving to welcome everyone into their galleries.

An art museum dedicated to serving the intellectual, spiritual, and social demands of a diverse community is worlds away from the elite microcosm of the early modern Wunderkammer. Yet, like its ancestors, it is a reflection of the world that produced it, and it tells us as much about the history of its—and our—times as it does about the things it contains.