For every period of Jewish history, interactions with non-Jews have been essential to forming Jewish culture and identity. The early Israelites made animal sacrifices at the Holy Temple, and they were distinct from other Levantine peoples, each of whom worshiped their local gods.

Symbolic representation of the ancient Temple of Jerusalem, Beth Shean synagogue floor mosaic, 5th–7th century C.E., stone, 276 x 435 cm (The Israel Museum, Jerusalem)

The Diaspora

Although there is no archaeological evidence for it, the Hebrew Bible describes a Temple in Jerusalem erected by King Solomon, probably sometime during the tenth century B.C.E. The Bible also describes the Temple’s destruction at the hand of the Babylonians 500 years later. Since the fall of the first Temple, Jews scattered throughout the Levant and Mesopotamia, creating competing cultures. Rabbinical scholars realized then that it would be necessary to write down oral interpretations—and they set the blueprint for future generations who would debate and reinterpret Jewish laws. The best-known rabbinical scholar was Hillel. Hillel developed methods for interpreting the Hebrew Bible that were flexible. Since its inception, Judaism has been subject to community ritual interpretation and context.

A new Temple was constructed a century after the first was destroyed when some Jews returned to the Land of Israel. In 70 C.E., at the Roman siege of Jerusalem, Jews dispersed throughout northern Africa, the Middle East, and the Mediterranean. This widespread dispersion of Jews outside of the Land of Israel is called the Diaspora.

The Middle Ages

Panel from a Torah Shrine from the Ben Ezra Synagogue in Cairo, 11th century, wood (walnut) with traces of paint and gilt, 87.3 x 36.7 cm (The Walters Art Museum). The patterns of vine scrolls and lozenges shows the influence of Islamic art.

In the Diaspora, Jewish groups lived in both Muslim– and Christian-dominated areas. Local communities had distinct traditions, but the differences between those who came from Muslim areas and those who came from Christian areas was more pronounced. Jews who can trace their ancestry back to Central and Eastern European areas are now known as Ashkenazim, and those who come from the Islamic world are now known as Sephardim. Sephardic Jews technically trace their origins back to the Iberian Peninsula, but Jews from the historically Muslim lands of the Middle East and North Africa (referred to as Mizrahi and Maghrebi, respectively), have been conflated with contemporary Sephardim since they share many of the same customs. These labels did not become widely used until the 1960s, when Jews from Islamic lands emigrated into Europe, the United States, and Israel. On a global scale, these distinctions weren’t relevant until after World War II.

In both Ashkenazic and Sephardic communities, Jews in the Middle Ages had to pay taxes in exchange for communal autonomy. Just as they came to speak the vernacular languages of the non-Jews among whom they lived, they also adopted the architectural, musical, culinary, and literary styles of their neighbors.

Synagogues in Christian-dominated lands are sometimes drab on the exterior but extremely ornate on the inside. Synagogues in Muslim lands have domes and arches that mimic Islamic architecture, such as the Santa María la Blanca in Toledo, Spain, or the Algiers Grande Synagogue in Algeria.

Ibn Shoshan Synagogue (now Santa María la Blanca), first built 1180, Toledo, Spain (photo: José Luis Filpo Cabana, CC BY-SA 3.0)

In Europe, persecution of Jews began after the Roman Emperor Constantine converted to Christianity. In the eleventh and twelfth centuries, crusading mobs massacred Jews throughout Europe. Crusaders blamed Jews for crucifying Jesus, an accusation that was extended in order to claim that Jews were committing the ritual murder of Christian children, known as the blood libel.

Jews who lived in Europe were easy, early targets for Crusaders since the Muslims, from whom they hoped to wrest the Holy Lands, were far from home. Throughout the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, Jews in Spain were subject to violent forms of anti-Judaism. The Spanish Inquisition forced conversions and expulsions of the many Jewish residents of the Iberian Peninsula.

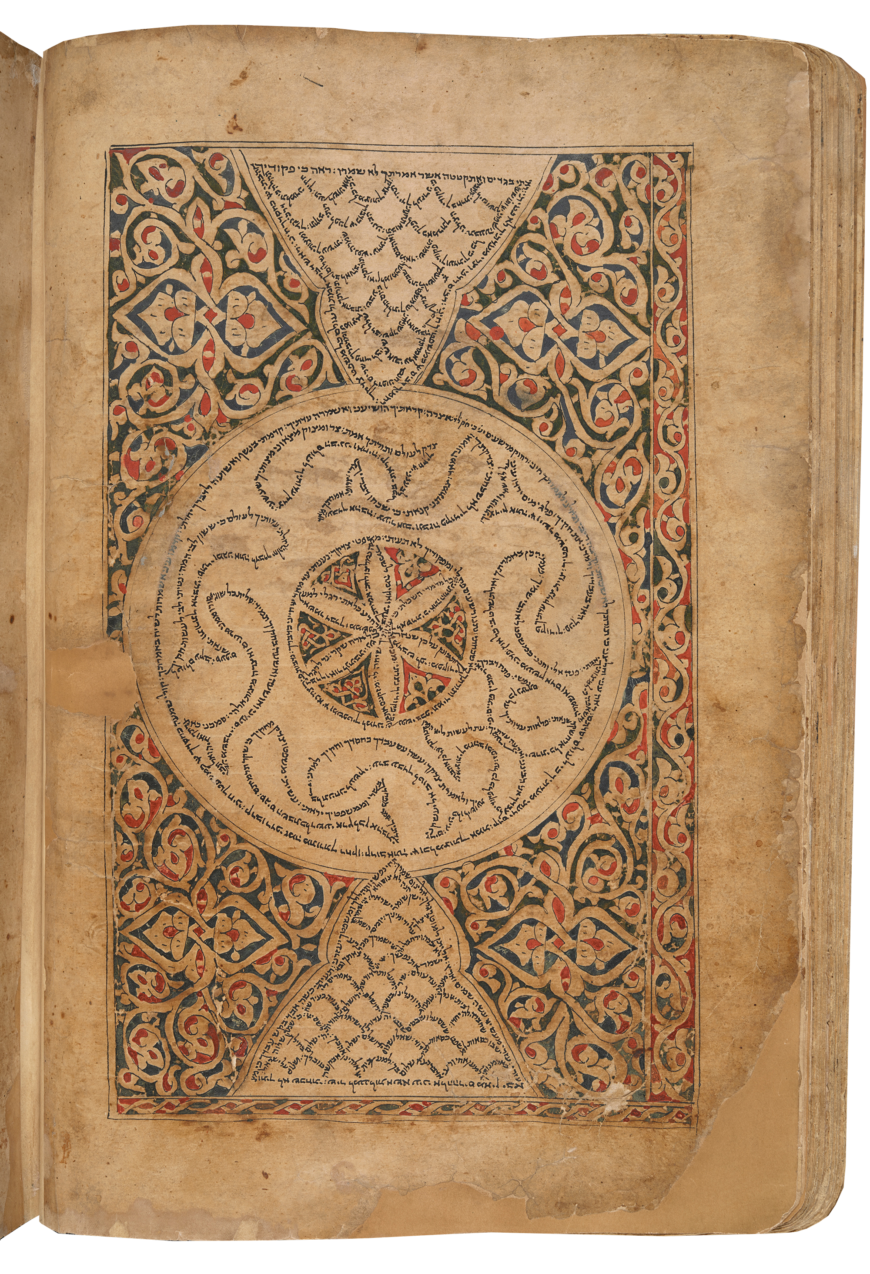

Folio from the Sana’a Pentateuch, 1469, illuminated manuscript, Sana’a, Yemen (British Library, MS 2348, fol. 38 verso)

Life for Jews in Islamic lands was comparatively tranquil. In areas dominated by Muslims, Jews in the Middle Ages were tolerated as a “dhimmi”—a people of the book. Unlike in the Christian world, Jewish people were not the only non-Muslim inhabitants (there were also Christians, Zoroastrians, Hindus, Buddhists, etc.). Jews were integrated into the economy, and they were allowed to practice their religion freely. Jews conducted business with non-Jews in the Middle Ages and the similarities in art, music, and food traditions speak to Jewish and non-Jewish interaction. But their communal lives remained mostly separate—Jewish dietary laws, or kashrut, meant that Jews had their own butchers, bakers, and even wine producers. The weekly Sabbath meant that Jewish merchants and peasants would refrain from work, while Christian or Muslim commerce might continue. And Jewish law forbid marriage outside of the religion, further solidifying boundaries between Jews and their neighbors—boundaries that in some later instances became walled ghettos within which Jews were forced to live.

Additional resources

Daniel Boyarin, Border Lines: The Partition of Judaeo-Christianity (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004).

Elisheva Carlebach, Divided Souls, 1500–1750 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2001).

Robert Chazan, The Jews of Medieval Western Christendom: 1000–1500 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006).

Mark R. Cohen, Under Crescent and Cross: The Jews in the Middle Ages (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1994).