Newark Museum: Exhibition of Clay Products of New Jersey, 1915, poster (The New York Public Library)

A great department store… is more like a good museum of art than any of the museums we have yet established.

—John Cotton Dana, “The Gloom of the Museum,” 1917

Chances are, when you were young, you preferred to hang out at the local mall rather than the local art museum. John Cotton Dana, the founding director of the Newark Museum in Newark, New Jersey, was a radical early-twentieth-century museum innovator who wanted to know why. What was it that the world of retail was doing that was so attractive to the general public? What lessons might museums take from retail to become socially “active and influential agencies”?

Dana thought that, as in retail settings, museum objects needed to be interesting, displays attractive, information freely available, and exhibits in regular rotation to keep people coming back. These were fairly novel ideas in 1917, and a century later they still have pull, but the idea of the museum as a social good has never been stable and continues to evolve. The department store is only one useful analogy. Today people call on art museums to act as schools, civic centers, economic engines, refuges, and town squares, shining a bright light on the needs of communities and the expectations they often have of their museums.

Museums and elites

European and North American museums have their roots in elite personal collections, which were housed in private spaces and open only to a restricted circle of friends and acquaintances, or those with proper letters of presentation—almost always wealthy, educated men. Although the range of visitors broadened somewhat with the founding of public museums in the eighteenth century, these remained exclusive and unwelcoming to most people.

Benjamin Sly, The British Museum: The Egyptian Room, 1844, engraving by Radclyffe (The Wellcome Collection)

The British Museum, for example—founded in 1753 as a gift to the nation to be “visited and seen by all persons desirous of seeing and viewing [it]”[1]—required until 1810 that applications for a ticket be submitted in advance, in writing. A punchy guide to London lamented that “idle girls, or … , still worse, idle men and women, may go and admire, for a few minutes… [but] the image[s seen] will soon be effaced from their minds, their understandings being as much darkened as their memories unretentive.”[2] Museums did little in the way of labeling or interpretation to help, and this impression of visitors too unprepared and too unintelligent to benefit from a museum’s collections prevailed.

Ironically, many public museums were founded with the intention of countering those perceived shortcomings—that is, to raise levels of general education and culture in support of an informed, engaged citizenry. In France, for instance, the Louvre laid out a clear message of national identity tied to cultural heritage: the distinctiveness of French art, its place in the larger artistic patrimony of mankind, and so forth. However, the space of the museum remained—and remains still to some degree today—mainly the realm of the elite.

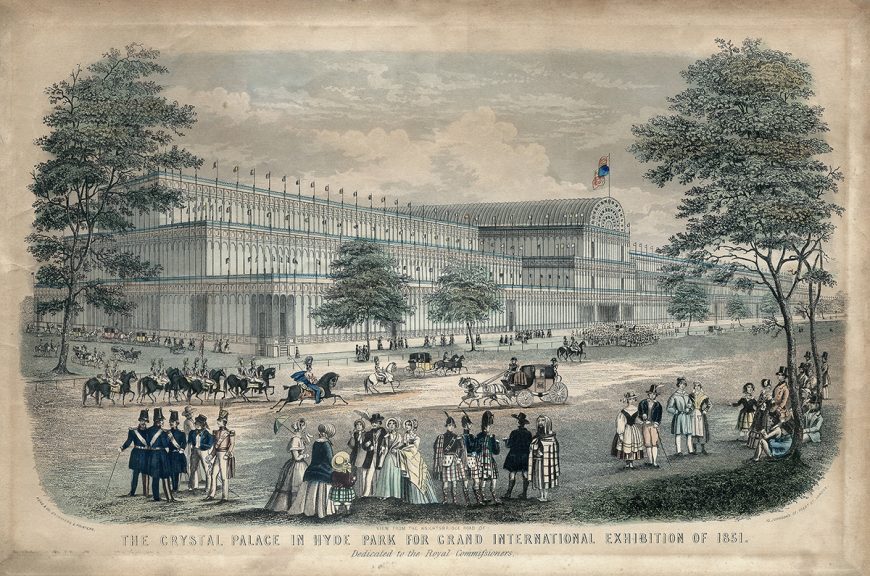

The Crystal Palace in Hyde Park for Grand International Exhibition of 1851 (Read & Co. Engravers & Printers)

The market as a driver of change

Joseph Nash, “An exhibition gallery representing Guernsey and Jersey, Malta and Ceylon,” from Dickinson’s Comprehensive Pictures of the Great Exhibition of 1851, 1854, watercolor, 33.3 x 48.4 cm (The Royal Collection)

In nineteenth-century Britain, much of the concern around who could and should visit museums centered on economic and class issues, as the Industrial Revolution radically transformed the nature of work and, by extension, urban and social structures. British industrialists felt pressured by goods imported in bulk from the colonies (Indian cotton, for example), and by manufacturing innovations in rival European nations (especially France) that threatened to displace their own products. One solution was to give their citizen-laborers better access to imported goods so that they could study, imitate, and ultimately challenge them. At the same time, lush displays of goods would stimulate consumer appetites, boosting demand and thus also production.

Out of these ambitions was born the first international trade fair, London’s Great Exhibition, held in 1851 in the newly built Crystal Palace (above). This massive structure of iron and glass was itself a marvel, at the time the largest enclosed space in the world, housing over 100,000 exhibitions. Displays were divided by geography (nations and colonies) and technologies, and organizers sought to balance spectacle and wonder with an educational agenda. Notably, their target audiences included the artisans and craftsmen who had been excluded from elite museums but who enthusiastically joined the throngs at the Exhibition.

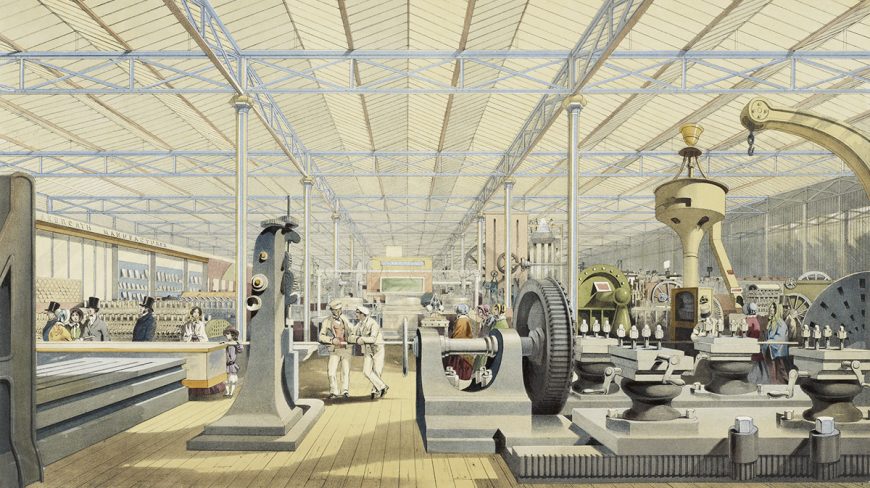

Louis Haghe, Moving Machinery, Dickinson’s Comprehensive Pictures of the Great Exhibition of 1851, 1854, pencil, pen and ink, watercolor, with touches of bodycolor and gum arabic, 29.5 x 54.5 cm (The Royal Collection)

Until this time, museums had not paid much attention to design; it was assumed that educated visitors would stay engaged through their inherent interest in the objects themselves. But at this giant trade fair, great care was given to installation, drawing attention to the workmanship, materials, and beauty of the objects on display, be they unfinished goods like textiles or finely crafted items for the home. Visitors were encouraged to look carefully, but not touch. Explanatory materials were plentiful, including written labels, attendants who demonstrated the machinery, and public lectures. Writer Henry Mayhew described the Crystal Palace as a giant schoolhouse—a far cry from the impenetrable museums of the day.

Thomas Abiel Prior, Queen Victoria Opening the 1851 Universal Exhibition at the Crystal Palace in London, 1851, 1851-86, watercolor with white gouache highlights, 20.5 x 40 cm (Musée d’Orsay)

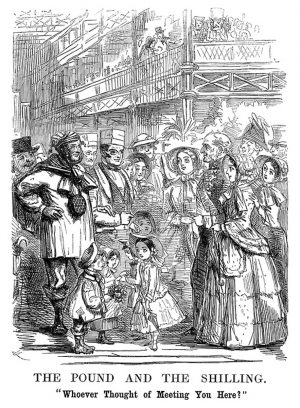

John Leech, The Pound and the Shilling. “Whoever Thought of Meeting You Here?” 1851 (Punch)

Beyond didactic learning about materials and technologies, organizers hoped their exhibitions would have a “civilizing” effect. Thus the Crystal Palace also presented “fine arts,” including sculpture, stained glass, and other objects “illustrative of the taste and skill displayed in the applications of human industry.”[3]

The hierarchy that distinguished “art” as being of the highest taste and skill implied a social hierarchy as well, allying this elevated category of production with those elites who could study, appreciate, and collect it. And yet even while the Crystal Palace seemed to reinforce social distinctions, it also pushed against them. For unlike the British Museum and its kin, the Great Exhibition was affordable to many. It was a place where the laborer and the lord literally rubbed elbows, as illustrated in this satirical image where the Duke of Wellington is astounded to encounter a working class family at the fair.

J.C. Lanchenick, South End of the Iron Museum (the “Brompton Boilers”), South Kensington, c. 1860, watercolor, 26.5 x 38.3 cm (Victoria and Albert Museum). This temporary museum structure was given the name “Brompton Boilers” based on an architectural critique published in a contemporary journal.

The Great Exhibition lives on

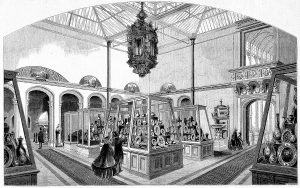

W.E. Hodgkin, Ceramics collections in the North Court of the South Kensington Museum, from The Builder, May 3, 1862, wood engraving (The Wellcome Collection)

London’s South Kensington Museum, founded in 1857 and renamed the Victoria and Albert Museum in 1899, was the literal heir to the Crystal Palace. Established to further the Exhibition’s goals of making exemplary objects of craft and industrial arts (as opposed to “fine” arts) available to the general public, a good part of its collection came directly from the fair. Objects were arranged first by medium—ceramic, metalwork, glass—that is, according to categories that made the most sense to a visiting artisan. These things were displayed to the public not to awe them with history, power, or authority, but to improve their lives by providing them with models of good form and taste.

The Victoria & Albert Museum today (photo: Diliff, CC BY-SA 3.0)

To that end, the museum made visiting easier as well. South Kensington’s first director, Henry Cole, welcomed working people by establishing opening hours on weekends, holidays, and evenings (necessitating the installation of gas lighting), adding free admission days, publishing transportation information, and constructing a refreshment hall. Although some critics feared Cole would attract “lunatics, derelicts, and suffragettes” who might damage the collections, the large crowds were remarkably well behaved, as found “in the best drawing rooms [of Europe].”[4]

These were innovative, even radical adaptations of the museum model, but we might pause before cheering too loudly. Like many of his contemporaries, Cole believed that through museums of art he could help instill proper manners, morals, and values in the visiting public—that he could help “civilize” them by “furnish[ing] a powerful antidote to the gin palace,” as he put it.[5] By today’s standards, his attitude was paternalistic, rooted in a certainty that he and others like him knew what was best for “the people.”

Whose museums?

A student learns how to add citations to Wikipedia articles during the AfroCROWD DEFCON 201 Wikipedia editathon on unsung Black artists, makers and innovators at the Newark Museum, August 5, 2017 (photo: Jim.henderson, CC BY-SA 4.0)

The idea that the art museum might be a morally acceptable space for aiding uprooted, itinerant urban dwellers is one that was taken up on the other side of the Atlantic as well. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, some American progressives saw museums as safe gathering places: reliable alternatives to the taverns and beer halls that might otherwise draw in and corrupt susceptible new arrivals to the big city. It took an innovator like John Cotton Dana at the Newark Museum to search for balance between a museum that could “better” the lives of city dwellers by teaching them upper-class values, and one that allowed visitors to engage with collections on their own terms.

Cai Guo-Qiang, I Want to Believe, 2009, installation in the Guggenheim Bilbao atrium (photo: Tony Hisgett, CC BY 2.0)

Art museums today continue to struggle with issues of social relevance, elitism, and ownership. Many professionals worry about “threshold fear,” the idea that museums intimidate visitors who were not raised in a museum culture and feel unwelcome and unrepresented in their galleries.

Others believe art museums are sacrificing their traditional role by bending to popular culture and the market, exhibiting motorcycles, tennis shoes, and runway fashions to draw in visitors. As museums become spaces of international attention, particularly tourism, some see them neglecting local communities: the Guggenheim Bilbao, for example, has been criticized for favoring famous international artists at the expense of regional ones.

The role of an expanding global museum paradigm is equally complicated. Should art museums underscore cultural continuities, perhaps encouraging empathy, or should they highlight cultural differences and express diversity? And who gets to decide? Clearly, museums have never been neutral spaces, and the conceit that they present widely shared social values to which we all aspire is wildly out of date. As the recent controversy over Dana Schutz’s painting of Emmett Till at the 2017 Whitney Biennial in New York City made clear, art museums in the early twenty-first century are charged political spaces where social struggles are being played out on powerful, highly visible stages.

Notes:

[1] Sir Hans Sloane’s will, cited in Rosemary Ashton, Victorian Bloomsbury (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2012), p. 133.

[2] Squire Randal’s Excursion round London: Or, a Week’s Frolic in the Year 1776 (London: Richardson and Urquart, 1777), p. 69.

[3] As described in the Great Exhibition’s Official Descriptive and Illustrative Catalogue (London, 1851), p. 23.

[4] Black, Barbara J. On Exhibit: Victorians and their Museums (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 2000), p. 104; and an 1882 report cited in Lara Kriegel, Grand Designs: Labor, Empire and the Museum in Victorian Culture (Durham: Duke University Press, 2007), p. 198.

[5] Cited in Edward P. Alexander, Museum Masters: Their Museums and their Influences, (Nashville: American Association for State and Local History, 1983), p. 163.

Additional resources:

A history of the Victoria & Albert Museum

Auerbach, Jeffrey A. The Great Exhibition of 1851: A Nation on Display (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1999).

Black, Barbara J. On Exhibit: Victorians and their Museums (Charlottesville and London: University Press of Virginia, 2000).

Dana, John Cotton. “The Gloom of the Museum” (1917), republished in Gail Anderson, ed. Reinventing the Museum: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives on the Paradigm Shift (Walnut Creek, Cal.: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers, Inc., 2004), pp. 13-29.

Gurian, Elaine Heumann. “Threshold Fear” (2005), republished in Civilizing the Museum: The Collected Writings of Elaine Heumann Gurian, (Oxon and New York: Routledge, 2006), pp. 115-126.

Maffei, Nicolas, “John Cotton Dana and the Politics of Exhibiting Industrial Art in the US, 1909-1929,” Journal of Design History, Vol. 13, No. 4 (2000): 301-317.