Hubert Robert, Design for the Grande Galerie in the Louvre, 1796, oil on canvas, 112 x 143 cm (Louvre Museum)

“It is to kill art to make history of it … .”Quatremère de Quincy, Considérations morales sur la destination des ouvrages de l’art<, 1807 (1815)

Take a good look at this statement. What does Quatremère de Quincy (“Catruh-mayre duh Cansie”) mean by “making history” with art? And what is this about killing?

Quatremère was writing in the thick of the raiding of churches and palaces that accompanied the French Revolution and Napoleon’s looting of European collections. He witnessed paintings and sculpture, architectural ornament and furnishings ripped from their original settings and taken to museums—which he considered to be mausoleums, cold places filled with lifeless things. Whether or not you agree with him, Quatremère had one thing right: in his day, none of the objects now considered “art” were made for display in museums of art history. Art was political, religious, or for personal use, but the emerging art museums, formed in the Enlightenment context of secularism and science, had little interest in those functions.

Museums aimed to forge a historical narrative that could explain, rationally and through a story of stylistic influence, how art had evolved over time. An altarpiece by Raphael, for example, was understood as the culmination of a developmental arc from late medieval devotional imagery to high classicism. Its life as a vehicle for worship was secondary at best, only important as it supported stylistic achievements.

Another way of thinking about Quatremère’s critique is to consider the art museum as its own kind of context, a place that shapes how we see and think about objects it contains. There are several primary interpretive tools that do this work, including the classification and arrangement of things, the mode of presentation, and what we might call the museum’s “ontological” attitude toward the objects on view—that is, how they are understood to exist in relation to other things in the world. The last of these is the most tricky but in many ways the most interesting, so our exploration will focus there, with attention to three collection matters critical to museums and their objects: authenticity, value, and permanence. (Issues of display and presentation are considered in the related essay, “Looking at Art Museums.”)

Authenticity

Cast gallery, V&A, London (photo: stu smith CC BY-ND 2.0)

We generally assume art museum objects are “authentic,” meaning that they are what they claim to be—true to the period, place, or person of attribution and to characteristic materials, forms, subject matter, and iconography. Art museums also place a high premium on originality, an understanding that each work is unique to a particular artist or, more rarely, group of artists. But these assumptions reflect what we might call the high modernist museum—a space built around a twentieth-century Euro-American notion of art. In the nineteenth century, even great museums like the Louvre and the Metropolitan displayed collections of plaster casts, where replicas stood in for the most famous sculptures of antiquity and the Renaissance. The objective of these collections was instructional: they allowed any museum to display famous works like the Laocoön or the Venus de Milo and thus tell the dominant story of art historical development, unlimited by financial resources or access to key works. Authenticity and the aura of the original object were secondary to education.

View of the cast collection of ancient sculpture in the former Franciscan monastery church in Hostinné. Part of the Cast Collection of Ancient Sculpture of the Institute of Classical Archaeology at the Faculty of Arts, Charles University in Prague (photo: Zde, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Today many types of museums (of history, science, and ethnography) rely on copies and replicas to tell their stories. Visitors to traditional art museums, however, still tend to expect an encounter with “the real thing.”

The antithesis of authentic objects are fakes and forgeries—things that are intended to fool people into thinking they are something they are not. Museums try mightily to avoid acquiring fakes, but sometimes mistakes are made.

These objects point to the complexity of copies and fakes. The Getty Kouros may be a forgery intended to fool the market; but the contemporary copy of the Mona Lisa was part of the Renaissance tradition of replicas, often made by or within the same studio as the original. Left: Kouros, c. 530 B.C.E. 206.1 x 54.6 x 51 cm (The J. Paul Getty Museum, CC BY 4.0); right: Apprentice of Leonardo da Vinci, copy of the Mona Lisa, 1503-16, oil on panel, 76.3 x 57 cm (Prado)

The most famous museum forgery debate in recent years surrounds the Getty Kouros, finally (for now) declared by the museum to be a fake. But between the genuine object and the intentional forgery there is a spectrum of authenticity that reveals the complexity of these categories.

For example, artistic training practices often prioritizes imitation as a way of learning and working, and in the tradition of Orthodox icon painting, an exact replica is a means for transmitting divine power. Sometimes objects are made as copies for the market and later became confused with forgeries as the history of the pieces and the intention of the maker got lost (as is the case with many late nineteenth-century copies of the wildly popular ancient Greek “Tanagra” figurines).

Some institutions have made a point of highlighting works of problematic authenticity, in some cases even exhibiting forgeries in their collection as teachable objects (for example the Walters Art Museum, Artful Deception: The Craft of the Forger, 1987-88, and the Brooklyn Museum of Art, Unearthing the Truth: Egypt’s Pagan and Coptic Sculpture, 2009).

Value

Relative Values: The Cost of Art in the Northern Renaissance, The Metropolitan Museum of Art (August 7, 2017 – June 23, 2019)

Duccio di Buoninsegna, Madonna and Child, c. 1290-1300, tempera and gold on wood, 27.9 x 21 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

We can think of authenticity as a form of “value,” a way of gaging the worth of an object, and the previous examples indicate that there are many ways to do this and many types of value. The most obvious of these is monetary value, something that art museums are particularly reluctant to discuss for reasons ranging from security to guarding knowledge about the way museums funds are spent (though in the case of public art museums much of this information is technically available on request). Museums prefer to elevate other reasons for treasuring their collection—aesthetic and historical ones, for example. But the price of an artwork is a question that fascinates the public.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s 2004 purchase of Duccio’s Madonna and Child for 45 million dollars made international news, and this figure remains a great point of interest for museum visitors. The Met turned this interest on its head in a recent installation, Relative Values: The Cost of Art in the Northern Renaissance, 2017-19, demonstrating the monetary value of artworks measured according to the cost of a cow in 16th-century Europe. Notably, the price of a fine Netherlandish oil painting was equal to five cows while a woven tapestry cost 52 cows. The modern museum places paintings at the top of the institutional hierarchy—the most prized in collecting and for exhibition—but even this simple example indicates how subjective that system of valuation is.

Permanence

A third framework for considering how museums classify and prioritize objects is the idea of permanence—material permanence, but also permanence in the sense of cultural authority. The idea of a “masterpiece” or a “canon of great works,” which guides much collecting and display, assumes that certain works are and always will be the most important in telling the history of art. This assumption has kept many artworks out of the museum, particularly those by women and minorities but also material by untrained artists (“outsider artists”) and even certain genres of art that are not broadly accepted as serious or significant.

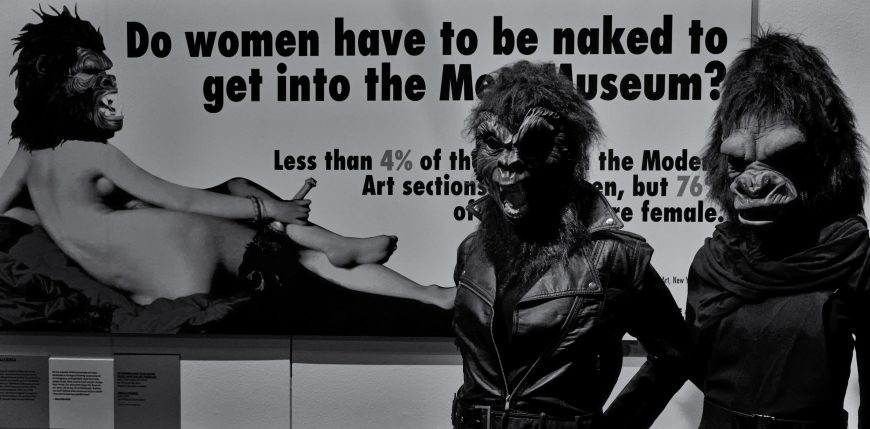

For many years, photography was not accepted by most preeminent art museums, for example. Artists and activists, such as the Guerilla Girls and those who founded the Museum for Women in the Arts, have worked hard to impact the ways museums shape artistic canons, and the objects they collect—which, tellingly, are termed “permanent collections.”

Guerrilla Girls – V&A Museum, London (Photo: Eric Huybrechts, CC BY-ND 2.0)

We can also think about permanence as a material question. Western art has long prized the power of art to endure—think of marble sculptures or of Renaissance portraits made to promote eternal fame. Indeed, preserving its collection from decay is one of the core obligations of museums. But some cultural traditions and some contemporary artists challenge that very premise.

Many indigenous groups in North America, for example, understand cultural objects as having a lifecycle that includes natural degradation and decay, while museum conservation works against those processes. Museum staff should at least be aware of that original context, and in the case of some materials—for example, sacred objects—consult with originating peoples about the most culturally appropriate care.

Many contemporary artists play with notions of permanence, employing time-based strategies of making or transient materials not intended to last. Zoe Leonard’s “Strange Fruit” is an example of artwork made to decay, while the sculptures of Nam Jun Paik rely on technologies that are destined to become obsolete, things like monitors, keyboards, and screens. In choosing to collect such art, museums must be willing to invest resources (money, space, expertise) into something they know will not last.

Nam June Paik, Electronic Superhighway: Continental U.S., Alaska, Hawaii, 1995, fifty-one channel video installation (including one closed-circuit television feed), custom electronics, neon lighting, steel and wood; color, sound, approx. 15 x 40 x 4′ (Smithsonian American Art Museum) (© Nam June Paik Estate)

Quatremère de Quincy’s lament over the killing of art objects was less about their literal demise than about the dislocation that removed them from their natural habitat and placed them in the alien, neutralizing space of the museum, remaking them as objects of inspection and instruction rather than of daily life.

Today, art museums are so commonplace that we can easily forget the systems of value that once made the objects they house meaningful. Yet many museums are increasingly attuned to this issue, exploring new techniques of display and interpretation to explain their institutional relationship with objects to the public—including questions of what and how they collect and how they manage those collections. Transparency in museum practice is an important step in helping visitors understand the ways that the museum context shapes the interpretation of objects.

Additional resources:

Gill Perry and Colin Cunningham, ed. Academies, Museums and Canons of Art (Yale University Press, 1999).

Menachem Wecker, “The Imitation Game,” The Washington Post Magazine, February 27, 2019.