By Ludovic Bertron from New York City, Usa – https://www.flickr.com/photos/23912576@N05/2942525739, CC BY 2.0, Link

The rainbow flag was designed by a group of volunteers led by artist and activist Gilbert Baker at the Gay Community Center in San Francisco, and first waved in the sky at the Gay and Lesbian Freedom Day Parade on June 25, 1978. Over the decades, it has become the most prominent symbol of Pride and equal rights advocacy for all people identifying as LGBTQ+ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and everybody else in an expansive community, including our straight allies).

As the concept of representation by the flag broadened over time, so its colors and their meaning changed: from the eight-stripe version of 1978, down to the most common six-stripe one, developed for practical reasons having to do with the availability of the colored fabric, up again to ten stripes.

As the Black community currently fights for equality and justice, we honor the people of color who are part of our LGBTQ+ community. Pride, as we know it today, grew out of the June 1969 Stonewall uprisings led by activists of color Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera. The SILENCE = DEATH campaign during the HIV/AIDS epidemic of the 1980s drove home the idea that when you say nothing, you’re complicit.

The particular version of the flag we decided to honor here includes the eight original colors (which stand for sexuality, life, healing, light, nature, magic, serenity, and spirit), plus brown and black, meant to symbolize the value of diversity and inclusion of all people.

As is the case with many effective symbols and great works of art, the rainbow flag was not born out of a single person’s stroke of genius, and its pole is firmly driven into several layers of history and popular culture. Starting at least from the 18th century, different versions of the rainbow flag have been used to symbolize different identities, beliefs, and struggles, such as Andean indigenous cultures, Buddhism, and the Peace Movement, to name a few.

Gilbert recounted on several occasions that the idea of making a flag came about during the United States’ bicentennial celebrations of 1976, when the stars and stripes were embraced as a symbol of national unity. (The artist, by the way, would sometimes dress in drag and adopt the name Busty Ross in honor of Betsy Ross, the upholsterer from Philadelphia who’s credited with making the first American flag.)

It has also been suggested that the rainbow was chosen as a reference to Judy Garland, a beloved intergenerational gay icon who first recorded the Academy Award-winning song “Somewhere Over the Rainbow” (from The Wizard of Oz). Like many songs that have become anthems in our community, “Somewhere Over the Rainbow” is about the hope and longing for a future “where troubles melt like lemon drops,” about overcoming all obstacles and becoming stronger and happier in the process.

I want to finish this brief introduction on a personal note. On June 26, 2015, while I was working at my desk at the Getty Research Institute, the US Supreme Court decided that the Fourteenth Amendment required all States of the Union to recognize same-sex marriages.

That same day, the Museum of Modern Art in New York installed in its foyer the flag, which had entered the design collection a couple of weeks earlier. I remember that day. I am an immigrant in this country, and thanks to that ruling, which led to a modification of federal immigration policies, I was eventually granted permanent residency in the United States.

With this colorful, joyous flag, we’re not just celebrating abstract symbols and ideas. We’re celebrating actual positive change in people’s lives. We’re celebrating ourselves, the people who came before us who fought for our rights, and the people who will come after us: their right to pursue happiness, to love, and to live the life of their choosing. Happy Pride, everybody!

~Pietro Rigolo

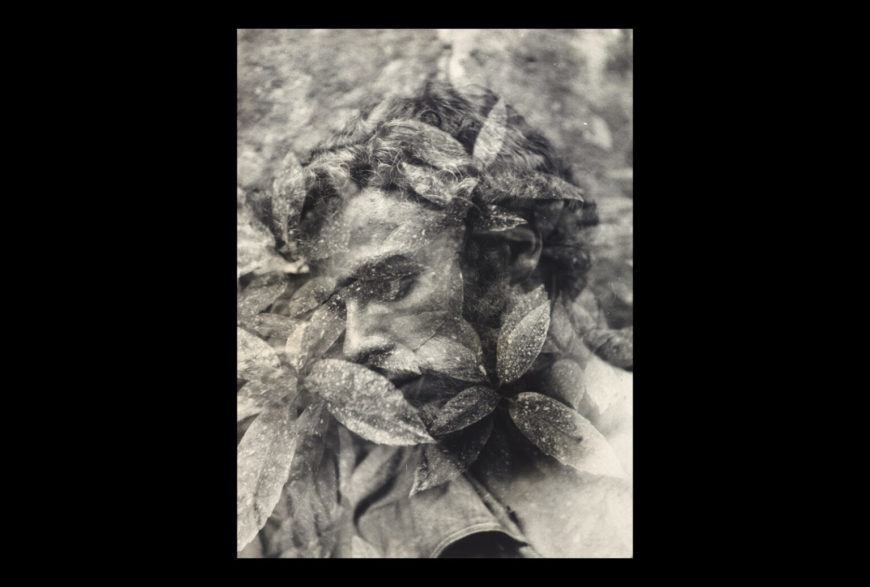

Portrait, about 1963, Emil Cadoo. Gelatin silver print, 15 1/4 × 11 7/16 in (© Estate of Emil Cadoo. Gift of Joyce Cadoo / Janos Gat Gallery. J. Paul Getty Museum, 2008.74.3)

Black: Diversity

The American photographer Emil Cadoo made this enigmatic photograph by combining multiple negatives, including a portrait of a young man in profile and one depicting foliage. The juxtaposition of these disparate subjects creates a dreamlike image and reveals his interest in Surrealism, a cultural movement born in the aftermath of World War I that carried considerable influence well into the second half of the 20th century.

After studying Romance languages at Brooklyn College with the help of the GI bill, Cadoo worked as a photojournalist. In the early 1960s, following in the footsteps of prominent American intellectuals including James Baldwin and Richard Wright, he emigrated to Paris, where as a queer Black man he found racism and homophobia to be less overt.

Cadoo had a successful career in France working for fashion magazines and political journals. His photographs appeared on the dust jackets of several books—including this image on the cover of the 1964 edition of Jean Genet’s Our Lady of the Flowers—and in the pages of the provocative and influential literary journal Evergreen Review.

~Arpad Kovacs

Mirror Study (0X5A6568), 2017, Paul Mpagi Sepuya. Pigment print, 51 × 34 in (© Paul Mpagi Sepuya. Purchased with funds provided by the Photographs Council. J. Paul Getty Trust, 2019.95.2)

Brown: Inclusion

For this picture, the artist fragmented an earlier photograph he’d made of an entangled embrace, and taped the pieces onto the smudged studio mirror into which he shoots his self-portraits. The legs of the artist’s camera tripod are visible at the base of the image, while his hands reach into the frame, helping to hold the pieces of the earlier composition in place.

Paul Sepuya’s work is intimate, foregrounding his body and relationships between bodies. The drapery and skin visible in the picture collaged onto the mirror call to mind the lush flesh and fabrics of 18th-century boudoir paintings, contrasting against the spare space of the artist’s studio. I’m drawn to this work because it reminds me that even when we feel most alone or isolated, we remain resolutely intertwined with others and with images. Pictures, like relationships, impact our sense of self and our images of ourselves.

When I think of Sepuya’s work I am heartened. His art is a poignant reminder of the power of connection.

~Mazie Harris

Attic Red-Figure Kylix, 510–500 B.C., Attributed to Carpenter Painter. Terracotta, 15 in (J. Paul Getty Museum. Digital image courtesy of Getty’s Open Content Program)

Pink: Sexuality

On the inside of this Athenian wine cup, a seated youth pulls his older lover down towards him for a kiss. Relationships between men and youths were a central component of Athenian aristocratic society, encompassing the cultivation of body and mind, proficiency at music and speech, and physical desire. According to literary sources, the beloved (eromenos) should behave in a modest way before the advances of his lover (erastēs), and some have noted that this cup is unusual in showing the youth reciprocating his aficionado’s advances. But I wonder—given that this scene would appear to a drinker as he consumed his wine—whether the scene is more likely an optimistic expression of a lover’s hopes?

~David Saunders

Achilles among the Daughters of Lycomedes, about 1625–1630, Pietro Paolini. Oil on canvas, 50 × 80 in (J. Paul Getty Museum, 78.PA.363)

Red: Life

As a child and adolescent struggling to understand my place in the world, I was always on the alert for works of art that seemed to question traditional notions of gender and sexuality in some way. While I wasn’t familiar with it then, I’m sure I would have been fascinated by this painting by Pietro Paolini, which depicts the Greek hero Achilles dressed as a woman, holding a shield and admiring a sword.

The painting is based on a legend in which Achilles’s mother, fearing her son would die if he fought in the Trojan War, entrusted him to King Lycomedes’s household, where he lived as one of the king’s daughters. When the Greeks arrived to find Achilles, they presented the daughters with gifts of jewelry and clothes but also a sword and a shield. Achilles reached for the weapons, revealing his “true” identity, and off he went to war.

A friend once remarked that this is “Achilles in drag,” and while that’s not quite right, it suggests an enduring cultural interest in what constitutes gender and what makes us who we are. I’m intrigued by the frequency with which this story of Achilles was depicted in paintings, opera, and other forms of art in the 17th and 18th centuries.

In matters of gender and sexuality, what is essential and innate? What involves a choice or performance? For me, celebrating the possibilities as we embrace the most authentic version of ourselves is one of the things that Pride Month—and life itself—is all about.

~David Bardeen

Documentation of the performance Free Fall 49, 2017, by Brendan Fernandes at the Getty Center, June 16, 2017

Orange: Healing

In June 2016, the Pulse nightclub in Orlando was the site of a horrific massacre targeting the Latinx and LGBTQ+ community celebrating Pride month. The year that followed was one of intense political change and frightening cultural shifts. In times like that, I always look to artists, who are inherently nuanced and multi-dimensional communicators, for a sense of clarity, a new perspective, and a pathway toward a shared sense of healing, even if in the abstract.

Artist Brendan Fernandes had been building a body of work to remember the 49 lives lost at Pulse, and used succinct and thoughtful gestures—an installation of 49 delicate hand-pulled crystal coat hangers, reminders of the coats taken off before hitting the dance floor, and a solo performer occupying a small gallery space, repeatedly falling flat to the ground in 49 moments of silence.

In June 2017, Fernandes expanded on those ideas for a performance of Free Fall 49 at the Getty Center. A feat of endurance across three hours, he directed eight dancers who emulated the movements of club dancing while on raised platforms scattered across the museum courtyard as music lured everyone into a dance party. At random, startling intervals, the music suddenly stopped and the dancers fell to the ground, snapping the crowd out of the present into a stark state of reflection. This was repeated 49 times.

As the artist and I prepared for this event, we wondered how the audience would react. Would they dance? Would they cry? Would they laugh? What ultimately happened was a complete surprise to me: the performance was not at all about the fall, but rather the act of getting back up again.

Each time the dancers rose from the ground and resumed dancing, it was euphoric. Every sudden stop offered a moment of renewal. The experience deftly spoke to the resiliency of the LGBTQ+ community that has continually found refuge together on the dance floor, and a community that has endured so much yet thrives in every way possible.

~Sarah Cooper

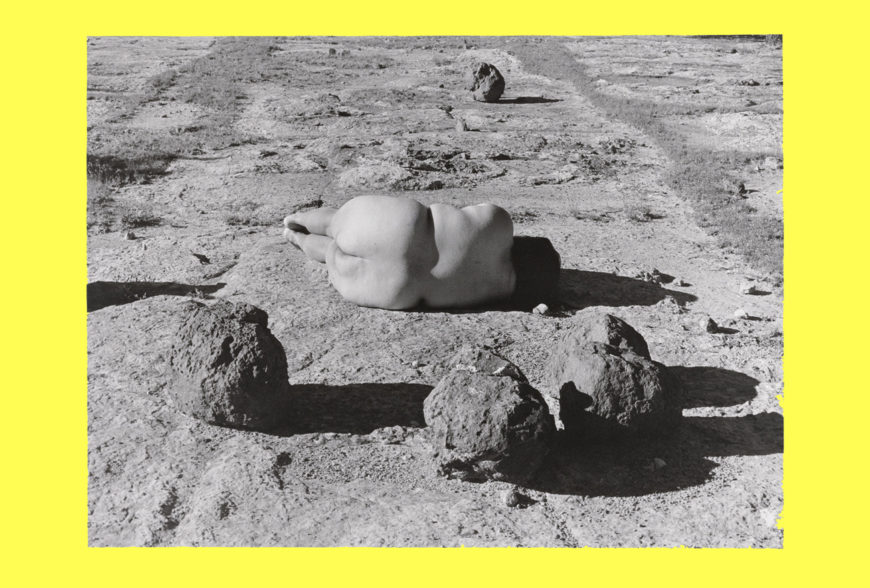

Nature Self-Portrait #2, 1996, Laura Aguilar. Gelatin silver print, 14 × 19 1/16 in (© Laura Aguilar Trust of 2016. Purchased with funds provided by the Photographs Council. J. Paul Getty Museum, 2019.19.2)

Yellow: Light

As a queer Chicana artist who grappled with mental health issues throughout her life, Laura Aguilar was able to connect easily with people on the margins of society. While she struggled with her sexuality, especially with openly identifying as a lesbian, she also drew upon this internal conflict to propel her photographic practice and made deeply compassionate portraits of fellow artists, authors, and activists, as well as sensitive self-portraits.

Aguilar regularly turned the lens of her camera on her own body as a way of coming to terms with long-held insecurities about her weight. Her nude self-portraits in the landscape reveal an interest in juxtaposing the fragile human form amidst the harsh conditions of the desert and with more bucolic scenes of a foliage-strewn riverbed.

In this image, she contrasts her exposed skin with boulders, mimicking their shape and position by contorting her frame to blur the distinction between human and non-human forms. The image suggests a way of looking at the landscape of the American West that is about cultivating a personal relationship.

~Arpad Kovacs

A Volcano in Auvergne, 1874, Aurore Dudevant (George Sand). Watercolor on paper, 4 1/2 × 6 in (J. Paul Getty Museum, 2009.37)

Green: Nature

Aurore Dudevant, better known as George Sand, was one of the most prolific authors of 19th-century France and had a rebellious reputation. She flouted traditional gender conventions by dressing in men’s clothing, smoking in public, and engaging in a number of high-profile affairs. Celebrated for her writing, Sand also enjoyed painting and drawing, a private undertaking that she took up in her later years.

Green represents nature in the Pride flag, and who better to encapsulate this theme than Sand, a force of nature whose love for the French countryside manifested in the settings of her novels and the subject matter she chose for her drawings.

In this “dendrite,” which is how Sand referred to her watercolors, the artist created the craggy surface of a dormant volcano by applying watercolor to a sheet of paper and crushing it with another. The resulting pooling of pigment outlines the crater’s ridges, and Sand situated the crevasse before distant mountains and under a cloudy sky.

~Casey Lee

The Chemical Wedding of Hermes and Aphrodite from Michaelis Majeri (detail), 1687, Matthäus Merian the Elder (Getty Research Institute, 1380-908)

Turquoise: Magic

What has always struck me (and everyone else) about the subject of alchemy is its bizarre approach to expressing science through art. Matthäus Merian’s engraving of a hermaphrodite being roasted is no exception.

In the original myth, Hermaphroditus is simply the offspring of the god Hermes and goddess Aphrodite, born with “male” and “female” sex organs. In alchemy, the figure is adapted into a symbol for creating the illusion of gold. Hermes, the Roman Mercury, stands for the element mercury. Aphrodite comes to be a symbol for copper. The island of Cyprus, her birthplace, was heavily mined in antiquity for copper (the word copper is actually derived from “Cyprus”).

Simply put, if one takes mercury, copper, and a sprinkle of genuine gold flake, and heats the mixture, the mercury bonds the gold to the surface of the copper, making it look like gold. (This process is called mercury amalgam gilding.) Poof. Magic. An illusion. This image is illustrating a scientific formula.

Alchemical imagery often expresses transformation by metaphorically toying with the ambiguity of gender as a physical illusion. Despite the offense that the term ‘hermaphrodite’ has for a contemporary community, there is something compelling in the way that this image vaunts alchemy’s ability to tap what is chameleon in physical identity.

Alchemy is a science tinged with spirituality and a spritz of artistic spirit. And among its most spirited expressions is… Poof. Magic. Gender’s a transitory illusion. True identity’s an embedded secret, waiting to be empowered.

~David Brafman

![The Martyrdom of Saint Sebastian (detail), 1469, Lieven van Lathem. Tempera colors, gold leaf, gold paint, silver paint, and ink on parchment, 4 7/8 × 3 5/8 in (J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 37 [89.ML.35], fol. 29)](https://smarthistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/10_vanLathem-870x587.jpeg)

The Martyrdom of Saint Sebastian (detail), 1469, Lieven van Lathem. Tempera colors, gold leaf, gold paint, silver paint, and ink on parchment, 4 7/8 × 3 5/8 in (J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 37 [89.ML.35], fol. 29)

Indigo: Serenity

Saint Sebastian was a Roman imperial captain who was shot with arrows by fellow soldiers because of his faith. In the late 1400s, manuscript illuminator Lieven van Lathem depicted Sebastian with a serene look on his face, as golden rays emerge to form a halo around his head.

A prayer across the pages reads, “Console us in times of tribulation, and bring us remedy in times of plague and epidemic.” Sebastian has long been a patron saint of queer individuals, especially during the outbreak of AIDS in the 1980s (see @theAIDSMemorial on Instagram) and for a spectrum of gay men specifically (from twinks to twunks, and from bears to the BDSM and leather scenes).

I’m fascinated by images of the saint — in churches, museums, saunas, and adult entertainment — and I like to reflect upon what his image or the evocation of his story reveals about historical concepts of the body (masc/fem or androgynous, beautiful and abject). A look across time at images of Saint Sebastian also provides a fascinating history of undergarments (note the codpiece above).

Numerous contemporary artists have referenced the saint in their art, including Ron Athey and Catherine Opie, Keith Haring, Kent Monkman, and Kehinde Wiley. The ubiquity of Saint Sebastian images in art finds a harrowing parallel in the litany of names and faces of LGBTQ+ individuals who have been murdered around the world, including Tony McDade and Nina Pop. We remember them during Pride.

~Bryan C. Keene

Untitled self-portrait, ca. 1900s–1910s, Elisar von Kupffer. Lantern slide (Getty Research Institute, 2011.M.30)

Violet: Spirit

Elisar von Kupffer, also known as Elisarion, was an Estonian-born poet, artist, and gay-rights activist. Together with his partner Eduard von Mayer, Elisarion founded a religion called Clarism, which tried to reconcile their faith and longing for an afterlife with their identity as queer men.

In 1900, von Kupffer published what is widely considered the first anthology of homoerotic literature. After living in Saint Petersburg, Berlin, and Florence, at the outset of World War I von Kupffer and von Mayer moved to Switzerland, where they would spend the rest of their lives.

Clarism attracted virtually no followers other than the couple. Nevertheless, between 1927 and 1939, the two built a temple to this new religion in Minusio, on Lake Maggiore, known as the Sanctuarium Artis Elisarion.

The entire temple was meant to symbolize a path from darkness to light, from duality to unity through a circuit that visitors would follow in a space filled with dozens of paintings by the artist. Von Kupffer was an amateur photographer, and would often use himself as the model for the figures in his paintings.

With Clarism, von Kupffer and von Mayer favored a vision in which two forces, one good and one evil, were always at play. These forces occupied two worlds in constant opposition: the Chaotic World, where humans lived, and the Clear World of the Blessed, which souls could aspire to reach through a series of reincarnations. The first characteristic of the Chaotic World is the existence of dualities, principally male and female. The blessed beings of their Clear World were instead conceived as beings beyond gender and sexual impulses, living in an eternal state of falling in love, and beauty worship.

~Pietro Rigolo

This essay first appeared in the iris (CC BY 4.0).