Amulet case, 19th century, silver, Italy, 7.8 x 7.2 x 1 cm (MFA Boston)

From cradle to grave, and throughout all the seasons of the year, Jewish life is filled with ceremonies—celebrations of births and weddings, and the observance of holidays at home and in the synagogue (the central place of Jewish worship). Over time, specific objects developed for the performance of these rituals. Because Jewish law does not specify the form of these ceremonial objects, their design and ornamentation reflects the varied artistic styles of the cultures among which Jewish communities have lived. As a result, every object offers a window into Jewish ritual and cultural life in a distinct time and place.

Ceremonial art and Jewish law

Jewish law (halakhah), thoroughly prescribes many aspects of Jewish life, including the celebration of holidays and significant life events, such as births, weddings, and funerals. However, the only ceremonial objects entirely dictated by Jewish law are the Torah, the most sacred Jewish work containing the five books of Moses, and the parchment scrolls inscribed with verses from the Torah that are affixed to the doorposts of Jewish homes (the mezuzah) and worn by adult Jews during weekday morning prayers (tefillin). Their appearance and form has remained consistent across time as a result of the clear stipulations of halakhah.

In contrast, for all other ceremonial objects, the leniency of Jewish law allowed for the adoption of new and diverse artistic approaches. The creation and embellishment of ceremonial objects stemmed in large part from the concept of hiddur mitzvah (literally meaning the beautification of a commandment). According to this custom, individuals should strive to enhance a ritual by moving beyond the basic demands of the law, using beautiful and precious materials. This gave rise to rich visual traditions that reflected the varied experiences of Jewish communities across time and space.

Left: Candlesticks, c. 1866, silver, Germany, 35.9 × 13.7 × 13.7 cm (Jewish Museum); right: Kiddush cup and saucer, 1803, Ottoman Empire, silver, 8.3 x 7.4 x 7.4 cm (Jewish Museum)

Candlesticks, lamps, and goblets

Johann Valentin Schüler, Judenstern, 1680–1720, silver, Frankfurt am Main (Germany), 56.5 × 37.5 cm (Jewish Museum)

Nearly all Jewish holidays begin with the lighting of candles and the recitation of Kiddush (literally meaning sanctification), a blessing over wine, as a means of separating the mundane from the holy. While the rituals themselves—the required blessings, the precise timing, and the amount of wine, among other details—were prescribed, the forms that the candlesticks and wine goblet take is not specified. In fact, nearly any candlesticks or drinking vessel—from plain glass cups to ornate silver goblets—could be used.

In the medieval period, the Jewish community adapted for its own use a star-shaped hanging lamp which was commonly used for lighting houses throughout Germany and elsewhere in medieval Europe. Each lamp consisted of a shaft from which was suspended a star-shaped container for oil and wicks, and a basin below for catching dripping fuel. By the 19th century, the type was so closely associated with Jewish rituals that it was known as a Judenstern, or Jewish star.

Jewish law does not specify the form or decoration of the cup for the wine (known as a Kiddush cup). While modern Kiddush cups often incorporate Hebrew inscriptions (such as the text of the blessing over the wine), or related motifs (such as images of grapevines), this was not always the case. Often domestic glass and silver vessels were used as they were more affordable or readily available. This makes it difficult to identify drinking vessels belonging to members of the Jewish community or as having been used explicitly for Jewish ritual purposes. In many cases, oral and recorded family traditions are the only way we know that some seemingly mundane vessels were used as Kiddush cups.

Shabbat

Havdalah spice container, c. 1550, silver, Frankfurt, 23.7 × 7.3 × 7.3 cm (Jewish Museum)

Shabbat, the Jewish day of rest is observed weekly from Friday night to Saturday night. In addition to refraining from work, it is a day intended for spiritual enrichment. Shabbat is welcomed with the ritual lighting of candles and the blessing of wine. The conclusion of Shabbat is marked with a similar ritual called havdalah (which literally means “separation”), which distinguishes between the holy Sabbath and the weekdays to come. The ceremony, performed both within the synagogue and at home, includes the recitation of blessings over a cup overflowing with wine, symbolic of the blessings for the upcoming week. The smelling of aromatic spices uplifts the soul before the week ahead, and the burning of a braided candle is symbolic of the distinction between light and darkness and the fire of the new week.

Special containers designed to hold spices are first described in Jewish sources in the 12th century. At this time, it was not unusual for Jews, Muslims, and Christians to create ritual objects for members of other faith communities. In this case, Christian silversmiths designed early spice containers based on vessels that they were familiar with from a Christian setting—such as censers, or incense burners which likewise let off aromatic odors in the performance of the Christian liturgy. Both censers and spice boxes were modeled on Gothic architecture. This 16th-century spice container is modeled on a four-story Gothic tower, incorporating rose windows on its third story, and pierced windows framed by an ogival arch on its fourth story, all capped by a pinnacle with four surrounding turrets.

Holidays

Passover

Left: Seder plate, c. 1480, ceramic lusterware, Spain, 57 cm (Israel Museum); right: Deep dish, c. 1430, ceramic lusterware, Valencia, Spain, 45.1 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Family at Passover Seder, Prato Haggadah, c. 1300, Barcelona (Jewish Theological Seminary)

In the spring, Jewish communities commemorate the exodus from Egypt (told in the second book of the Hebrew Bible, Exodus) at a ritual meal called a Seder, which marks the beginning of the Passover holiday. At the Seder, families use a book called a haggadah (plural: haggadot), which recounts the story of the Exodus. Elaborately illustrated haggadot began to be produced in the 14th century, giving birth to a rich and varied tradition of manuscript illumination and book printing for the Passover Seder.

The Seder plate, containing a variety of ceremonial foods which symbolize elements from the Passover story, adorns the center of the Seder table. Although Jewish law delineates the specific foods, it does not specify the container. The earliest known surviving seder plate dates to 15th-century Spain, where Sephardic Jews created ceramic lusterware plates specifically for the purpose of the Seder. Lusterware was an especially desirable, luxury medium in Spain, and across Europe. Once again, without any specifications for the Seder plate’s design, artisans turned to local visual traditions. Adorned with Hebrew inscriptions, this remarkable Seder plate testifies to the vibrant Jewish material culture of Spain prior to the expulsion of the Jews from Spain and Portugal in 1492 and 1536, respectively. The tradition of decorating Seder plates spread throughout Europe, with artisans continuing to draw on local aesthetics and materials, making plates decorated with scenes from the Passover story, or of the Passover table and its guests. Modern Seder plates have incorporated contemporary artistic traditions, introduced humor, and made space for new ritual foods.

Hanukkah and Purim

Although likely among the most well-known Jewish holidays, Hanukkah and Purim are considered less significant, since they are not mentioned in the Torah, but were added to the cycle of the Jewish year by the rabbis in the 1st to 6th centuries.

Hanukkah lamp, 19th–early 20th-century, silver, Essaouira (?), Morocco, 27.7 x 30.4 x 10.3 cm (Jewish Museum)

The holiday of Hanukkah celebrates a group of Jewish rebel warriors (the Maccabees), who defeated the Greek army, and rededicated the Temple in Jerusalem, which had been defiled by the Greek army. During the cleansing of the Temple, they discovered that only a single jar of oil had survived to light the Temple’s menorah (candelabra). While it should have lasted only one night, the oil miraculously lasted for eight days. As a result, the central ritual of Hanukkah is the lighting of the hanukkiah (pl. hanukkiot) or Hanukkah lamp. Jewish law requires the lighting of eight candles, all set at the same level, customarily lit by a ninth light, (shamash) usually placed higher than the rest. Aside from these stipulations, the form of the hanukkiah is otherwise unspecified.

In 13th- and 14th-century Germany, Jewish artisans devised a new form for the hanukkiah—wall-hung lamps. Looking at examples of hanukkiot from around the world, we find that while this format continued to be used, it, as well as other forms, was adapted to local artistic traditions in each region. A hanukkiah from Morocco, for example, has a silver backplate adorned with incised rosettes with radiating petals as well as gilded rosettes soldered to the metal surface—both typical of jewelry produced in western Morocco in the 19th century.

Esther scroll with zodiac wheel, c. 1800, Ottoman Empire,5.9 x 72 cm (Braginsky Collection)

The holiday of Purim celebrates the survival of the Jews of Persia from the hands of the wicked Haman, principal minister to the King of the Persian Empire (also called the Achaemenid Empire), who plotted to exterminate all of Persia’s Jewish subjects. According to the biblical Book of Esther, a young Jewish woman named Esther, with the help of her cousin Mordechai, married the Persian king Ahasuerus and exposed Haman’s plans to him, saving her people. The story of Esther is read every year on Purim in synagogues around the world.

Beginning in the 16th century, miniature illustrated scrolls (megillot, singular: megillah) housed in ornate wooden and silver cases were created for members of the congregation to follow along during the service. An early 19th-century megillah from the Ottoman Empire opens with an image of the zodiac wheel. The zodiac was a popular motif in decorated megillot, as according to some interpretations, when Haman plotted to destroy the Jewish people, he consulted the zodiac to determine an auspicious time to carry out his scheme. He ultimately decided on the Hebrew month of Adar, which corresponds to the sign of the Pisces (fish). The illuminator of this Ottoman megillah drew attention to Pisces, by illustrating the fish on a larger scale and outside of the zodiac wheel.

The rhythm of Jewish life

The major transitional stages of Jewish life—birth, marriage, and death, are likewise marked by ceremonies that create a time-honored framework.

Birth and circumcision

Parents’ hopes and dreams for their children as well as the anxieties of childbirth (particularly with the high infant mortality rates and dangers to the mother in the pre-modern world), fueled the production of an array of amulets and talismans intended to protect an expecting mother and her newborn. While this practice is found in many faith communities, Jewish amulets are distinctive in their use of Hebrew inscriptions, often drawn from traditional Jewish sources.

Amulet for the eastern wall for the protection of pregnant women and their newborns, 18th–19th century, ink on vellum, Kurdistan, 43 x 58cm (The Magnes Collection of Jewish Art and Life)

For example, this early 19th-century paper amulet from either Iraqi Kurdistan or the Kurdish community in Jerusalem, together with three other paper amulets, was used to guard against infertility and infant death. At the center of the amulet, we see a throne surmounted by a winged creature, representing Lilith, a mythical character in Jewish tradition, who was believed to have been Adam’s first wife and who sought to hurt women in childbirth and their newborns. To balance out Lilith’s evil intentions, the names of Adam and Eve are inscribed on the throne, as well as the names of one of four angels believed to ward off Lilith—Sanoy, Sansanoy, Samengalaf, and Samangalon. Surrounding the central image are prayers, blessings, biblical quotations, names of God, and mystical formulae inscribed in Hebrew, Aramaic, and (Ladino or Judeo-Spanish). While Hebrew and Aramaic were the languages of religious tradition in the Jewish community of Kurdistan, the presence of Ladino suggests that this amulet was used by members of the Sephardic community living in Kurdistan—Jews who traced their ancestry to Spain and Portugal. Each of the four amulets was placed upon the walls of the birthing room and infant’s nursery, protecting the rooms from all sides. This amulet was used to protect the eastern wall, as “Samengalaf, the Prince of the East,” is inscribed within the center of the hybrid creature.

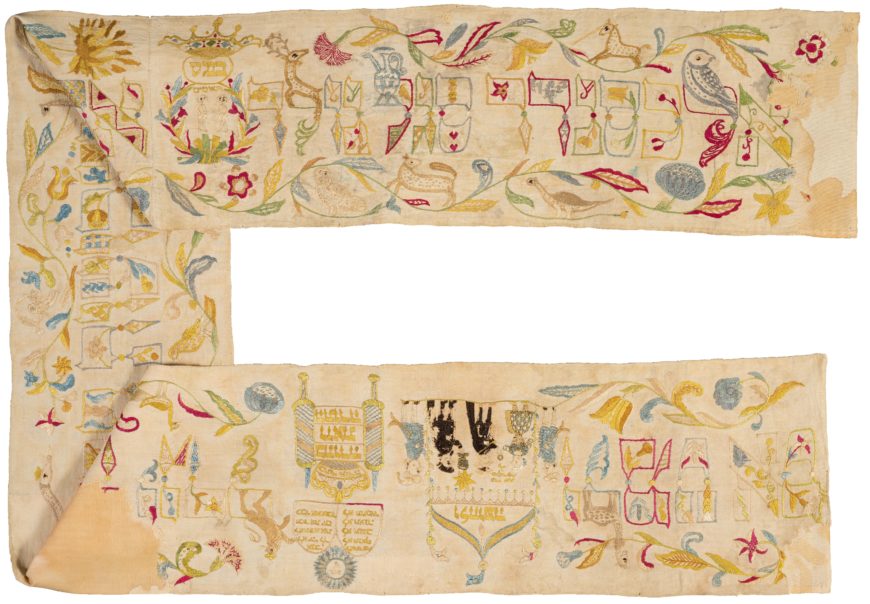

Torah binder (wimpel), Germany, 1750, linen and silk thread, 20.3 x 196.2 (Jewish Museum)

While amulets reflect a popular reaction to the dangers of daily life, the circumcision ceremony (performed on the eighth day of a baby boy’s life), dates back to biblical times. Symbolizing the covenant between God and the prophet Abraham, the ceremony marks the male child’s entrance into the Jewish covenant. In German-speaking lands, a unique tradition developed: the swaddling cloth used during the circumcision ceremony was transformed into a sacred object—a binder for the Torah scroll, meant to hold the staves of the Torah together when it was not in use. This binder, known as a wimpel, was elaborately embroidered with ornament and a lengthy inscription featuring the name of the child, the name of his father, and his Hebrew date of birth, followed by a blessing expressing the parents’ hopes for their child: “May he grow to [the study of] Torah, to chuppah (the wedding canopy), and to perform good deeds. Amen.” The family dedicated the wimpel to the synagogue, symbolically binding them to the Torah and the Jewish community.

This 18th-century Torah binder from Germany features a colorfully embroidered Hebrew text surrounded by animal and vegetal ornament. Towards the conclusion of the inscription, the binder includes a depiction of a wedding ceremony as well as an open Torah scroll surmounted by a crown and the two Tablets of the Law, referencing the inscribed wishes for the child.

Depiction of a Jewish wedding ceremony with the bride and groom standing beneath a chuppah (wedding canopy) as they exchange rings. Moritz Daniel Oppenheim, The Wedding (Die Trauung), 1866, oil on canvas, 66 x 54.4 cm (Jewish Museum)

Weddings

Ketubah, Livorno, Italy, 1751, pen, ink, gouache, and gold paint on parchment, 53.3 x 34.5 cm (Jewish Museum)

While several of the items used in a Jewish wedding ceremonies are indistinguishable from those made for Christians (such as drinking vessels), some objects are singular in their association with Jewish weddings—marriage contracts (ketubot, singular: ketubah) and medieval Jewish wedding rings.

One of the most carefully prescribed elements of the Jewish marriage ceremony is the ketubah, initially created to protect the status and property of a wife in case of divorce, or upon the death of her husband. Jewish marriage contracts have survived from as early as the 5th century B.C.E., but their format as we know them today was largely developed during the 1st through 6th centuries C.E. In modern times, the text of the ketubah has been further modified by some Jewish communities to reflect a more egalitarian approach. Although a strictly legal document, over time, the decoration of the ketubah became a way to broadcast a family’s status, and to enhance and personalize the marriage ceremony.

Made in regions around the world, ketubot reflect the artistic traditions of the communities in which they were produced. An 18th-century ketubah from Livorno, Italy, for example, features an elaborate architectural frame decorated with colored marble inlay and two putti (angels) raising a cartouche with the biblical scene of the sacrifice of Isaac. The biblical image likely refers to the bride’s father, Isaac Yeshurun. However, the remainder of the ketubah’s decoration was modeled on the work of sculptor Giovanni di Isidoro Baratta, who designed the altar for the Cathedral of San Ferdinando in Livorno as well as sculptural decoration for other churches in Livorno. He also designed the Synagogue of Livorno’s Torah ark, now destroyed. In this case, the ketubah not only draws upon the visual language then popular in Italy, which favored an exceptionally ornate aesthetic, but also refers to specific works of art visible in the city. The putti on the ketubah closely resemble those on the altar of the Cathedral of Livorno, while the colored inlay and decorative cartouches once appeared on the Torah ark.

Left: Jewish ceremonial wedding ring from the Colmar Treasure, c. 1300, before 1348, gold and enamel, made in Italy (?), 3.5 x 2.3 cm (Musée de Cluny); right: Jewish wedding ring, first half 14th century, gold, Germany, 4.8 x 2.5 x 2.5 cm (Thüringisches Landesamt für Denkmalpflege und Archäologie, Weimar)

In the medieval period, a wedding ring developed that was specifically associated with Jewish wedding ceremonies. These rings are crowned by miniature buildings inscribed with the Hebrew phrase, mazel tov, meaning good luck, a wish commonly expressed at weddings. As marriage is often equated with the formation of a new household, the building crowning the ring is an apt symbol for the commitment between bride and groom. Most of these rings were discovered in the 19th century buried among personal and communal treasures. These items were likely buried in the 14th century, during the era of the Black Death which ravaged Afro-Eurasia. Many Jews were blamed and persecuted for the devastation that the plague brought. These treasures likely belonged to Jewish families and communities who fled persecution in the wake of the Plague. A ring discovered in Erfurt, Germany is a remarkable example of early 14th–century gold craftsmanship. It is surmounted by a Gothic-style building, and carried by two winged dragons, which form the ring’s hoop. Inside the house is a small golden ball which gently rings when it is moved.

Left: glass for a burial society’s annual banquet, 1713, glass, enamel paint, Prague, Bohemia, 24.5 x 15.7 cm (The Israel Museum); right: beaker of the burial society of Worms, Johann Conrad Weiss, 1711/12, hammered, engraved, and parcel-gilt silver, Nuremberg, Germany, 24.8 x 12.5 cm (Jewish Museum)

Mourning and Death

The end of life is marked by solemnity and reverence. The Jewish customs of death, burial, and yahrzeit (the anniversary of a death) are carefully planned to ease the pain of the bereaved. In many Jewish communities, an organized burial society (hevra kaddisha) prepares the deceased and arranges the burial.

During the second half of the 16th century, the rabbis of Prague formed the first modern Jewish burial society. Like European Christian guilds and confraternities the European Jewish burial societies likewise cared for the ill, the deceased, and the deceased’s families. Also like Christian guilds, the hevrot kaddisha held festive banquets and commissioned precious vessels, both glass and silver. One of the few surviving enameled glass beakers produced for the burial society of Prague on the occasion of the society’s annual banquet, depicts male mourners proceeding around the circumference of the glass in a funeral procession. Inscriptions on the glass refer to death and mourning as well as the imperative to drink wine in celebration of life.

In the 18th century, the Burial Society of Worms, commissioned a leading silversmith, Johann Conrad Weiss, from the distant city of Nuremberg to create a silver beaker for their society. Twenty years later, when the society’s membership had grown, they commissioned a second beaker, this time made by a local silversmith. Beakers such as these were used to induct members into the society at the annual banquet. At the conclusion of the meal, new members were invited to drink wine from the ceremonial cup.

Left: memorial lamp (kandil), 19th century, Anti-Atlas Mountains, Morocco, 38.1 x 19.1 x 16.5 cm (Jewish Museum); right: memorial lamps in the Reuven Ben Sadoun Synagogue, Des, 1920 (Ariel Fein, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

In North Africa, for one year following an individual’s death, it was customary for family members to light a memorial lamp inscribed with the deceased’s name at home on Shabbat and holidays. Following the conclusion of the memorial year, the lamp was donated to the local synagogue. Together with other memorial lamps, their light served to continually remind the members of the congregation of their departed loved ones.

Whether for the observance of holidays or lifecycle events, ceremonial objects have become an essential element of Jewish visual culture. The remarkable diversity of these works, informed by the many communities among whom Jews have lived, are evidence of this vibrant Jewish artistic tradition.