The Christian Bible has had a long and complex genesis. The term “bible” is derived from the Greek word βιβλία (books), which in turn is based on the Greek word for papyrus (βύβλος or βίβλος). (Throughout antiquity papyrus was the principal material from which books were made.) As reflected in its name, the Christian Bible is a book made up of many books, incorporating the Jewish bible, known as the Hebrew Bible (Tanakh) as its first section. The Hebrew Bible is referred to by Christians as the Old Testament (derived from the Latin word testamentum, in the sense of dispensation or covenant). The Christian Bible also includes a smaller corpus of Christian texts as its second section, the New Testament. Although the Christian Church regards both Testaments as inspired, it also holds as a fundamental doctrine that the New Testament bears witness to the fulfillment of the Old.

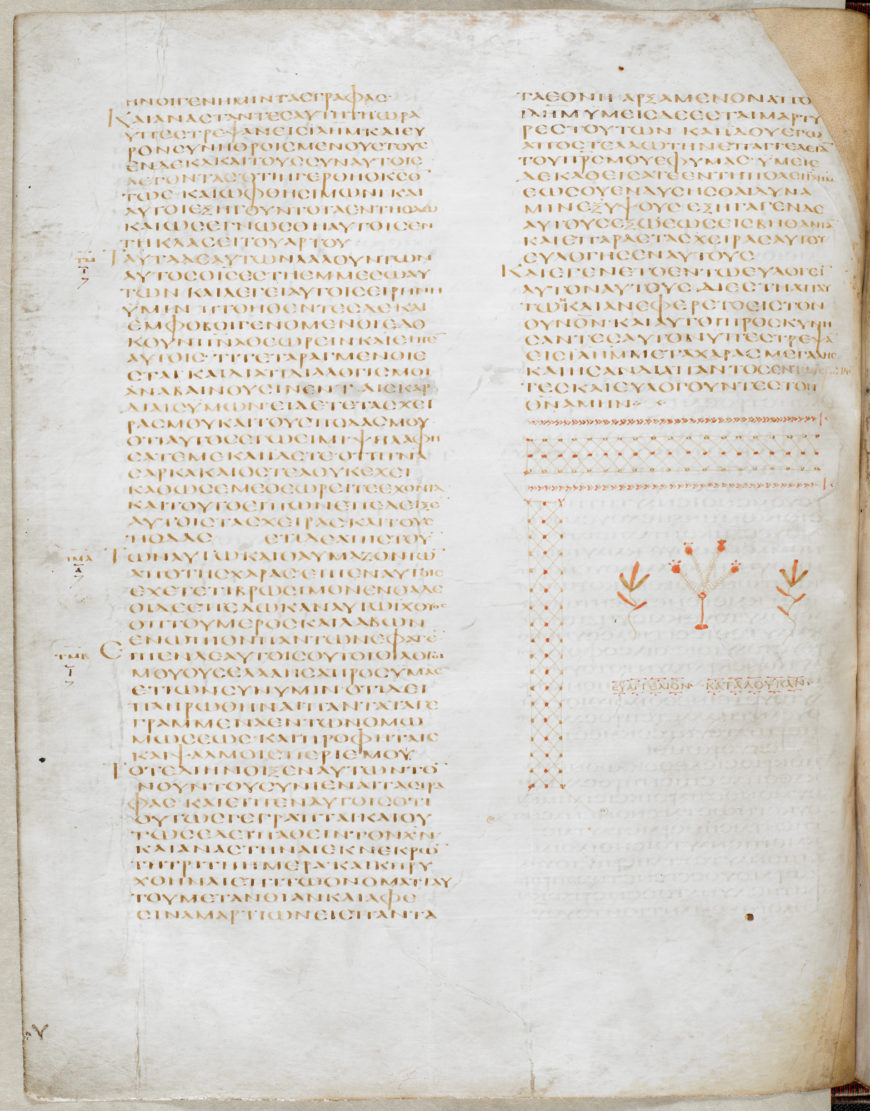

The Gospel of St Luke, from the fourth volume of the Codex Alexandrinus, from the 5th century. It is one of the three early Greek manuscripts that preserve the Old and New Testaments together. (British Library)

What does the Old Testament consist of?

Early Christians adopted a Greek version of the Jewish scriptures that had been produced for Jews residing in Egypt and other Greek-speaking territories, who were less familiar with Hebrew. Known as the Septuagint (“seventy” in Latin), this translation was traditionally attributed to seventy or so scholars working in Alexandria for Ptolemy II Philadelphus (308–246 B.C.E.). The Septuagint has at its heart the three key elements of Jewish scripture.

The first, the Torah, is traditionally ascribed to Moses and comprises the five books from Genesis to Deuteronomy. The second is the twenty-one books of the Prophets, including the twelve Minor Prophets. The third, the Writings, comprises thirteen assorted books: the Psalms, Proverbs, Job, the Song of Songs, Ruth, Lamentations, Ecclesiastes, Esther, Daniel, Ezra, Nehemiah and Chronicles 1–2. The shaping of these thirty-nine books had evolved over nearly a millennium.

The Septuagint also contains several texts that are excluded from the canon of Jewish scripture, most notably Tobit, Judith, the Wisdom of Solomon, Ecclesiasticus (Sirach), Baruch, and the two books of Maccabees. These texts were thus accepted by early Christians, who developed their canon based on the Greek rather than the Hebrew version of the Jewish scriptures.

When St. Jerome (c. 342–420; see below) undertook the translation of the Bible into Latin, he advocated that the Church follow the Jewish canon, and designated these extra texts as Apocrypha (from ἀπόκρυφος, ‘hidden’). Because the Protestant reformers of the sixteenth century used copies of the Jewish Hebrew canon of Scripture as the basis for their translations, these texts either do not form part of Protestant Bibles, or are included in them separately as apocrypha or deuterocanonical books. The apocrypha do, however, remain part of Roman Catholic and Orthodox Bibles.

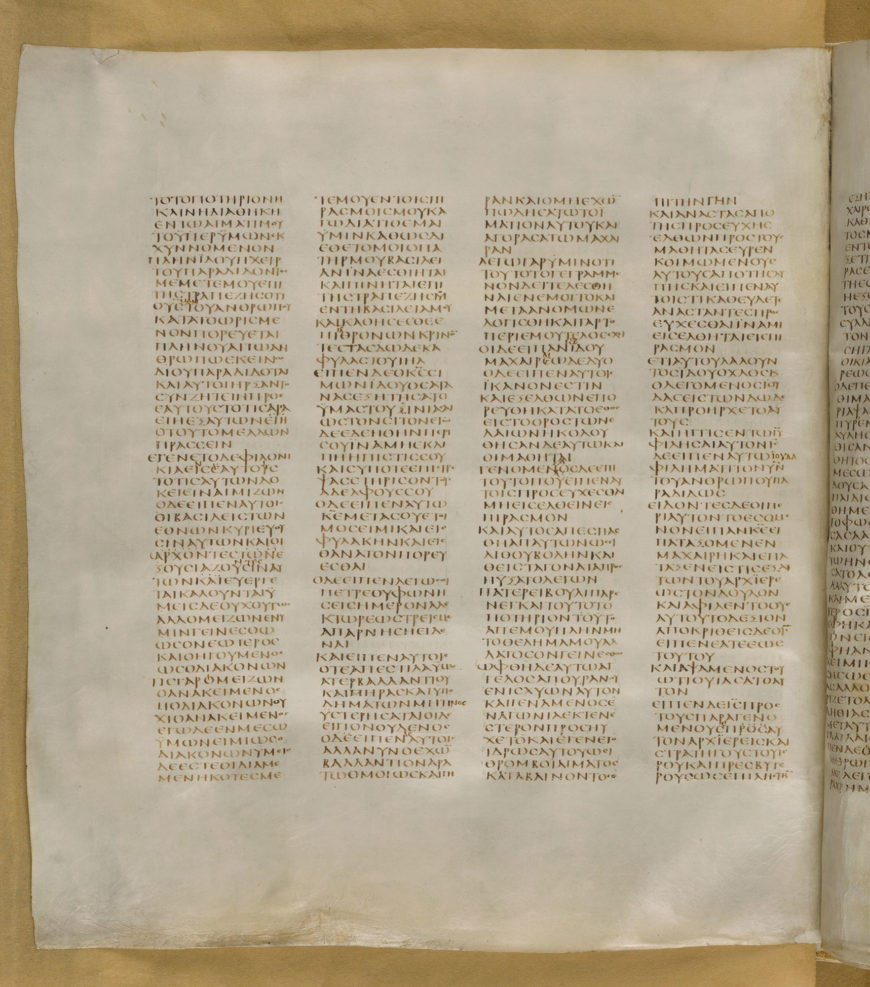

Produced in the Eastern Mediterranean during the early 4th century, the Codex Sinaiticus preserves the earliest surviving copy of the New Testament (British Library)

What is the New Testament?

Whereas their opinions differ over the Old Testament, Protestants, Roman Catholics, and Eastern Orthodox Christians all accept the same New Testament canon. This was formed over a much shorter period than the Jewish scriptures, but similarly comprises several distinct texts. The core of the New Testament is the Four Gospels. The word “gospel” is possibly derived from the Old English translation of the Latin word evangelium, which is itself based on the Greek εὐαγγέλιον (good news) and is the origin of the term for the authors of these texts, the Evangelists. Initially, many accounts of the Gospel were in circulation, and some, like the Gospel of Nicodemus, continued in popularity through the Middle Ages.

However, the Four Gospels of Saints Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John were widely accepted as uniquely authoritative from an early date. Their Gospels comprise individual witnesses to the life, teachings, death, and resurrection of Jesus of Nazareth, and to his status as the Christ (“Anointed One”), or Messiah, predicted in the Old Testament. The other twenty-three books of the New Testament include the Acts of the Apostles, in which St. Luke recounts the life of the Church immediately after Jesus’s ascension; letters to early Christian communities or individuals written by the Apostle Paul and other early Christian leaders; and an apocalyptic account, or revelation, traditionally attributed to St. John.

Although the core of the New Testament canon (the Four Gospels and thirteen Epistles of St. Paul) was established by the middle of the second century, the full canon of twenty-seven books was formally confirmed only during the fourth century. Until then, some books, such as Hebrews and Revelation, were in doubt, and other texts, such as the Epistle of Barnabas and Shepherd of Hermas, were considered authoritative by some Christians. All of the books of the New Testament were originally written in Greek, the language of the predominant literate community in the region, to further the evangelizing purpose of the New Testament.

Early translations of the Bible

By the fourth and fifth centuries the language of the Bible had changed. As the Christian faith spread to other regions and nations, their Scripture was also translated into other languages, beginning with those of the earliest converts. Known to biblical scholars as the Versions and recognized by them as important witnesses to the earliest forms of the text of the Bible, these texts included translations into Coptic, Syriac, Armenian, Georgian and Ethiopic.

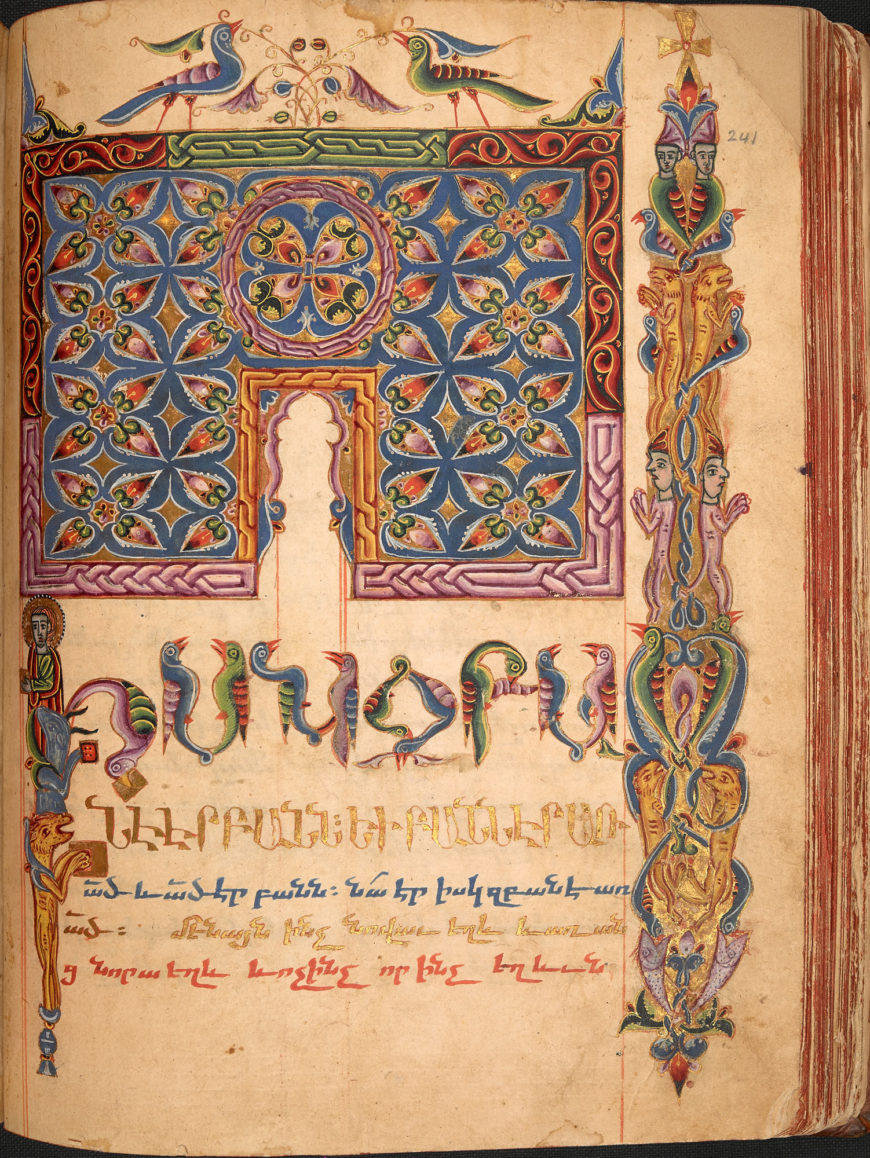

The opening of St John’s Gospel, from an early 17th-century Armenian Gospel book (British Library)

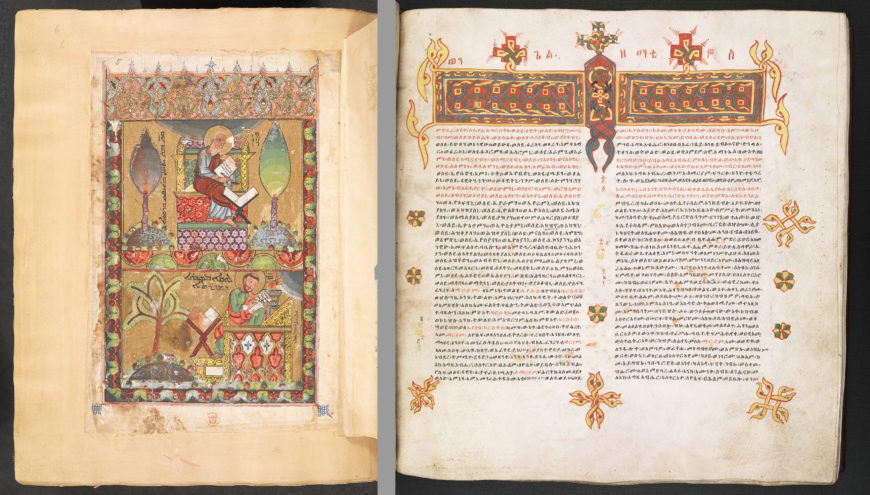

Through the work of Syriac missionaries, Syriac translations were widely disseminated into Persia, Arabia, India, and Central Asia, and gave rise to the earliest versions in other languages used in those areas, such as Armenian. The Syriac Gospel Lectionary from the early thirteenth century, the Armenian Gospels from the early seventeenth century and the Ethiopic Octateuch and gospels from the late seventeenth century demonstrate the continued use of these Versions over many centuries. Versions include some additional books, such as the Third Epistle to the Corinthians cited by St. Gregory the Illuminator (d. 332), which was included in many later copies of the Armenian New Testament.

Left: A 13th-century representation from a Syriac Gospel lectionary of the Evangelists St John and St Luke writing the opening words of their Gospels (British Library). Right: The beginning of the Gospel of St Matthew, from a late 17th-century Ethiopian Octateuch and Gospel (British Library)

In the West major changes also occurred. By the end of the second century, Latin was the most widely used language in the West, and Old Latin versions of the Bible were circulating in both Gaul (a historical region in Western Europe) and North Africa. More significantly for the future, the early Christian scholar St. Jerome initiated a translation and revision of the complete Bible into Latin, authorized by the Pope.

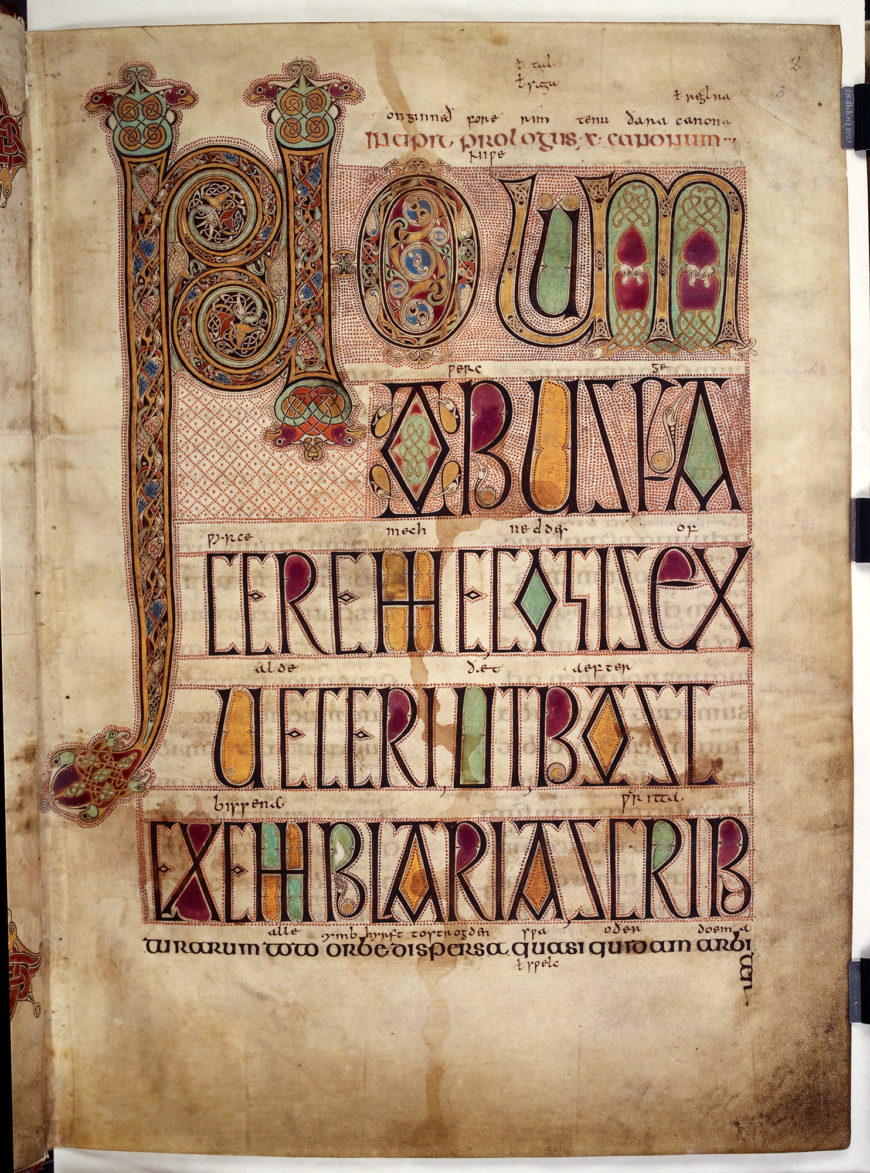

St. Jerome’s letter to Pope Damasus, who commissioned the translations of the Bible, appears at the beginning of the Lindisfarne Gospels, c. 700 (British Library)

Working first in Rome and then in Bethlehem, he used Hebrew and Greek texts, but also drew on the Old Latin versions. St. Jerome spent around half his life on his translations, and even then may not have himself progressed in the New Testament beyond the Gospels. He also purposely excluded several of the books of the Old Testament that he regarded as apocryphal.

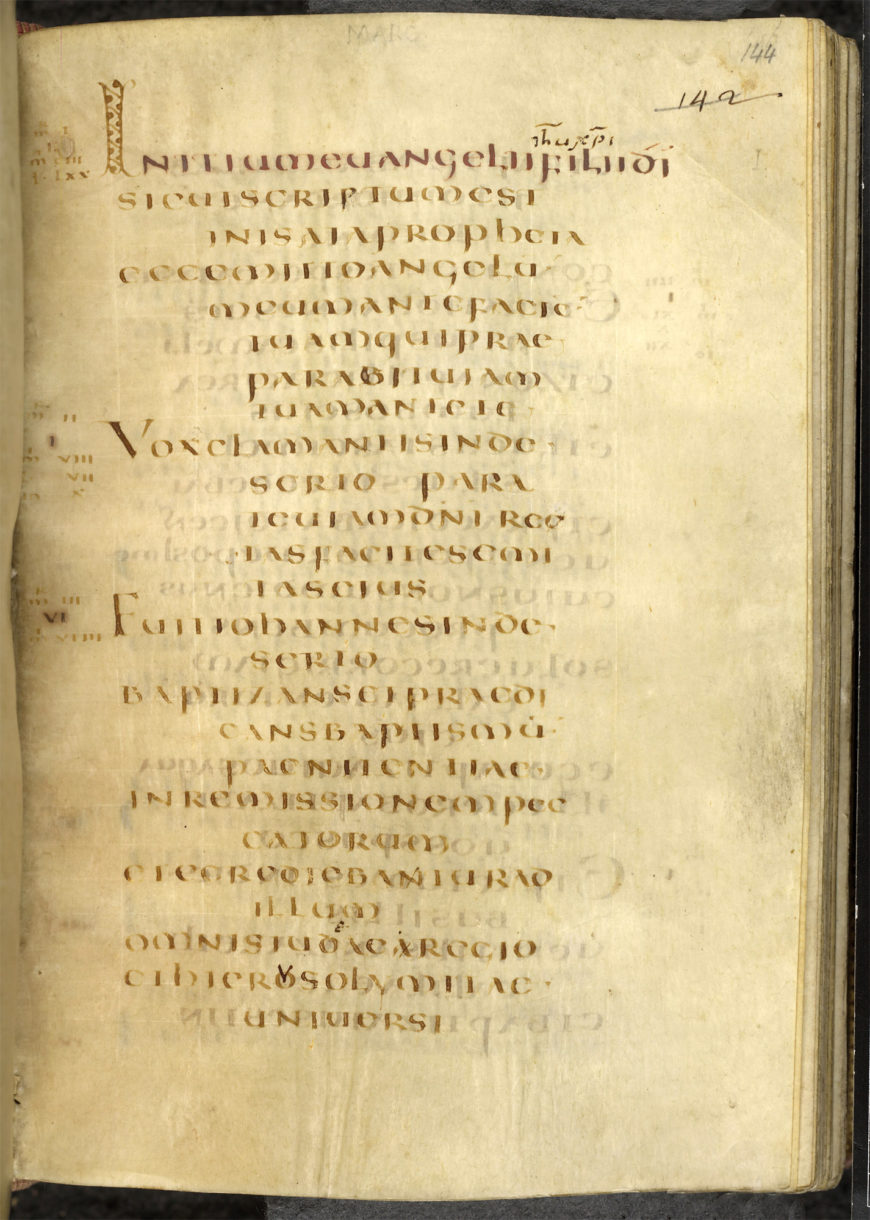

The Harley Gospels is one of the earliest surviving examples of St. Jerome’s Vulgate – the Bible in the ‘everyday Latin’ translation that was the standard version used by Christians for over a thousand years. It was created sometime in the last quarter of the 6th century. (British Library)

The use of Old Latin versions persisted for several centuries. Some manuscripts included texts that fused both the Old Latin and St. Jerome’s translation. St. Jerome’s exclusion of apocrypha was also reversed and Old Latin versions used to supply perceived gaps. In fact, the whole text had to be corrected at various points, for example by Alcuin of York for Charlemagne. St. Jerome’s legacy to the Church was, however, critical. The Vulgate (or common) Latin version that St. Jerome had initiated became the single, authoritative version of Christian Scripture in Western Europe for over one thousand years.

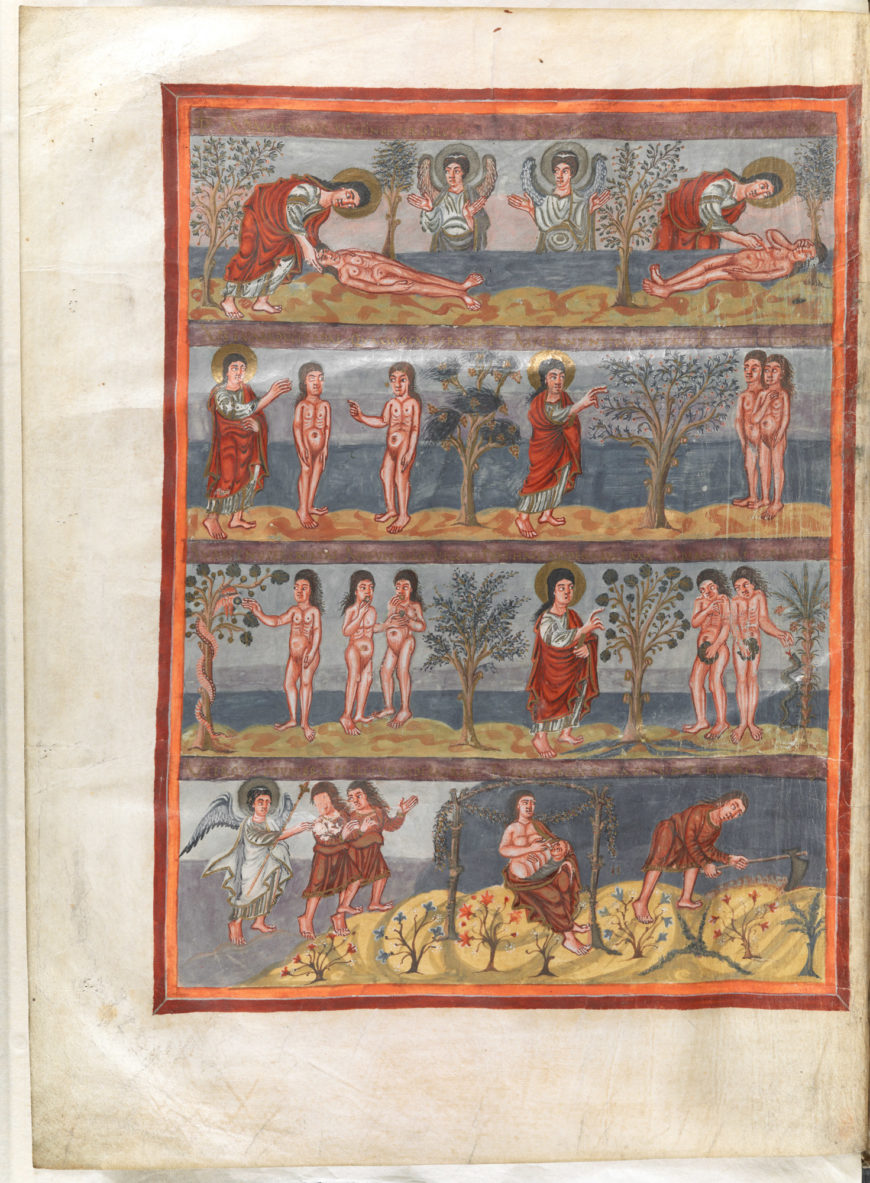

A 9th-century full-page illustration of the Fall in Eden from the Moutier-Grandval Bible (British Library)

During this period all translations of the Bible into Western vernacular languages were made from the Vulgate. None was regarded as having the authority of its model. They were regarded as aids to understanding the Scripture, not as Scripture itself. Only the Reformation brought new authoritative Western translations of the entire Bible based on the original Hebrew and Greek texts. These vernacular translations of the Bible in Europe in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries formed the basis of what we now read as the Bible.

From The British Library (CC BY-NC 4.0)