Taj Mahal, Agra, India (photo: David Castor)

What is Islamic Art?

The Dome of the Rock, the Taj Mahal, a Mina’i ware bowl, a silk carpet, a Qur‘an; all of these are examples of Islamic art. But what is Islamic art?

Islamic art is a modern concept, created by art historians in the nineteenth century to categorize and study the material first produced under the Islamic peoples that emerged from Arabia in the seventh century.

Today Islamic art describes all of the arts that were produced in the lands where Islam was the dominant religion or the religion of those who ruled. Unlike the terms Christian, Jewish, and Buddhist art, which refer only to religious art of these faiths, Islamic art is not used merely to describe religious art or architecture, but applies to all art forms produced in the Islamic World.

Thus, Islamic art refers not only to works created by Muslim artists, artisans, and architects or for Muslim patrons. It encompasses the works created by Muslim artists for a patron of any faith, including Christians, Jews, or Hindus, and the works created by Jews, Christians, and others, living in Islamic lands, for patrons, Muslim and otherwise.

One of the most famous monuments of Islamic art is the Taj Mahal, a royal mausoleum, located in Agra, India. Hinduism is majority religion in India; however, because Muslim rulers, most famously the Mughals, dominated large areas of modern-day India for centuries, India has a vast range of Islamic art and architecture. The Great Mosque of Xi’an, China, is one of the oldest and best preserved mosques in China. First constructed in 742 C.E., the mosque’s current form dates to the fifteenth century C.E. and follows the plan and architecture of a contemporary Buddhist temple. In fact, much Islamic art and architecture was—and still is—created through a synthesis of local traditions and more global ideas.

View of the Great Mosque of Xi’an, Shaanxi, China (photo: Alex Berger, CC BY-NC 2.0)

Islamic art is not a monolithic style or movement; it spans 1,300 years of history and has incredible geographic diversity—Islamic empires and dynasties controlled territory from Spain to western China at various points in history. However, few if any of these various countries or Muslim empires would have referred to their art as Islamic. An artisan in Damascus thought of his work as Syrian or Damascene—not as Islamic.

As a result of thinking about the problems of calling such art Islamic, certain scholars and major museums, like the Metropolitan Museum of Art, have decided to omit the term Islamic when they renamed their new galleries of Islamic art. Instead, they are called “Galleries for the Art of the Arab Lands, Turkey, Iran, Central Asia, and Later South Asia,” thereby stressing the regional styles and individual cultures. Thus, when using the phrase, Islamic art, one should know that it is a useful, but artificial, concept.

In some ways, Islamic art is a bit like referring to the Italian Renaissance. During the Renaissance, there was no unified Italy; it was a land of independent city-states. No one would have thought of one’s self as an Italian, or of the art they produced as Italian, rather one conceived of one’s self as a Roman, a Florentine, or a Venetian. Each city developed a highly local, remarkable style. At the same time, there are certain underlying themes or similarities that unify the art and architecture of these cities and allow scholars to speak of an Italian Renaissance.

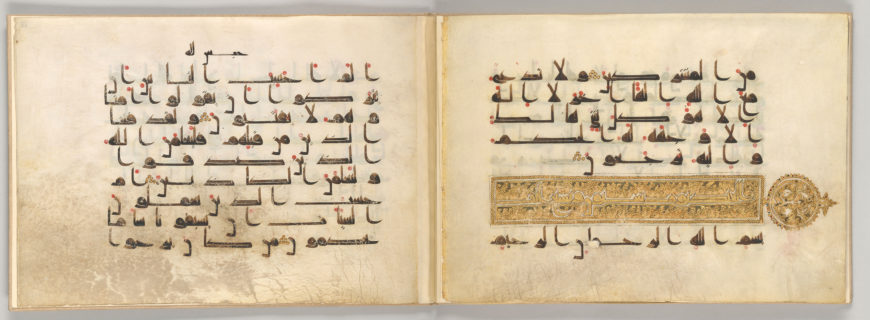

Qur’an fragment, in Arabic, before 911, vellum, MS M. 712, fols 19v-20r, 23 x 32 cm, possibly Iraq (The Morgan Library and Museum, New York)

Themes

Similarly, there are themes and types of objects that link the arts of the Islamic World together. Calligraphy is a very important art form in the Islamic world. The Qur’an, written in elegant scripts, represents Allah’s (or God’s) divine word, which Muhammad received directly from Allah during his visions. Quranic verses, executed in calligraphy, are found on many different forms of art and architecture. Likewise, poetry can be found on everything from ceramic bowls to the walls of houses. Calligraphy’s omnipresence underscores the value that is placed on language, specifically Arabic.

Geometric and vegetative motifs are very popular throughout the lands where Islam was once or still is a major religion and cultural force, appearing in the private palaces of buildings such as the Alhambra (in Spain) as well as in the detailed metal work of Safavid Iran. Likewise, certain building types appear throughout the Muslim world: mosques with their minarets, mausolea, gardens, and madrasas (religious schools) are all common. However, their forms vary greatly.

Bathing scene on west wall of west aisle of audience hall, Qasr ‘Amra, c. 730, Jordan (photo: Sean Leatherbury/Manar al-Athar)

One of the most common misconceptions about the art of the Islamic world is that it is aniconic; that is, the art does not contain representations of humans or animals. Religious art and architecture, almost from the earliest examples, such as the Dome of the Rock, the Aqsa Mosque (both in Jerusalem), and the Great Mosque of Damascus, built under the Umayyad rulers, did not include human figures and animals. However, the private residences of sovereigns, such as Qasr ‘Amra or Khirbat Mafjar, were filled with vast figurative paintings, mosaics, and sculpture.

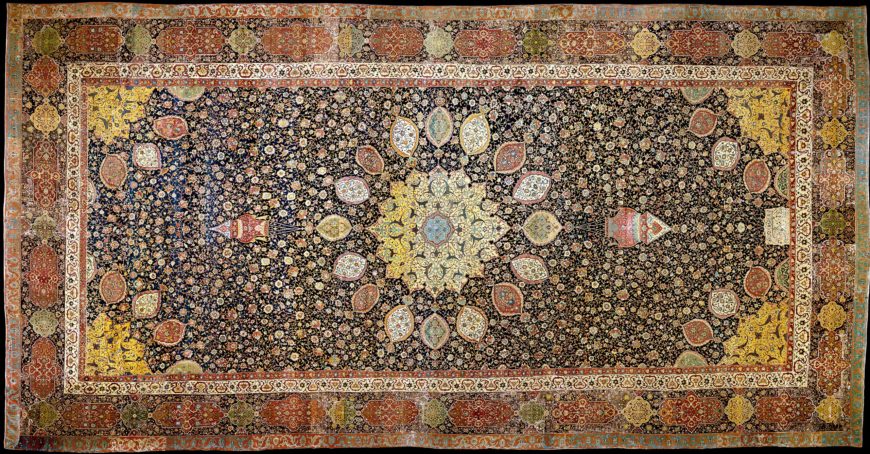

The study of the arts of the Islamic world has also lagged behind other fields in art history. There are several reasons for this. First, many scholars are not familiar with Arabic or Farsi (the dominant language in Iran). Calligraphy, particularly Arabic calligraphy, as noted above, is a major art form and appears on almost all types of architecture and arts. Second, the art forms and objects prized in the Islamic world do not correspond to those traditionally valued by art historians and collectors in the Western world. The so-called decorative arts—carpets, ceramics, metalwork, and books—are types of art that Western scholars have traditionally valued less than painting and sculpture. However, the last fifty years has seen a flourishing of scholarship on the arts of the Islamic world.

Medallion Carpet, The Ardabil Carpet, unknown artist (Maqsud Kashani is named on the carpet’s inscription), Persian: Safavid Dynasty, silk warps and wefts with wool pile (25 million knots, 340 per sq. inch), 1539–40 C.E., Tabriz, Kashan, Isfahan or Kirman, Iran (Virginia & Albert Museum, London)

Arts of the Islamic world

Here, we have decided to use the phrase “arts of the Islamic world” to emphasize the art that was created in a world where Islam was a dominant religion or a major cultural force, but was not necessarily religious art. Often when the word “Islamic” is used today, it is used to describe something religious; thus using the phrase, Islamic art, potentially implies, mistakenly, that all of this art is religious in nature. The phrase, “arts of the Islamic world,” also acknowledges that not all of the work produced in the “Islamic world” was for Muslims or was created by Muslims.

Note on organization from the contributing editor

We have organized the material in this section into three chronological periods: early, medieval and late. When starting to learn about a new area of art, chronological organization often enables students to grasp the material and its fundamentals before going on to more complex analysis, like comparing building types or styles. Within each of these chronological groups, we have focused on creating geographic groups or groupings to organize the material further. The Islamic world was only unified very briefly in its history under the Umayyads (661–750 C.E.) and the early Abbasids (750–932 C.E.). Soon various dynasties or rulers simultaneously commanded sections of territory, many of which had no cultural commonalities, aside from their religion.

We are also planning to upload a series of introductory essays on major types of art and architecture from the Islamic world, including carpets and mosques, in addition to essays and videos about specific works of art and architecture. These are forthcoming.

Arabic, Persian and Turkish are complex languages whose transcription from their respective scripts to English has changed considerably over time. For the sake of ease, we have used the most common forms today, omitting the vocalizations. While we have aimed for consistency, we have also tried to use the simplest forms for those who are new to the arts of the Islamic world.