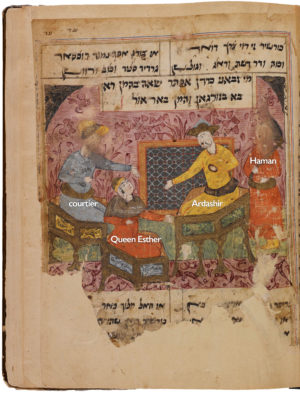

Queen Esther entertains the King in the presence of courtiers, Ardashirnama, late 17th century, Iran (The Library of the Jewish Theological Seminary)

A biblical book transformed

Detail, Queen Esther entertains the king in the presence of courtiers (The Library of the Jewish Theological Seminary)

This book illumination depicts four figures seated on ornamented thrones in a lavishly decorated palace. Floral motifs adorn the walls and lush carpets cover the floors. In the foreground, gazing up at her king, sits Queen Esther.

We might expect this to be the biblical Esther, whose story is told in the Book of Esther, which recounts the story of a young Jewish girl named Esther who lived in the Persian Empire, in what is today Iran. In this story, Queen Esther learned of a plot by the king’s principal minister, Haman, to exterminate all of ancient Iran’s Jewish subjects. With the help of her cousin, Esther exposed Haman’s plans to the king and saved her people. The Book of Esther is read every year by Jews around the world on the holiday of Purim.

This painting, however, does not depict the story of the Book of Esther. Rather, it comes from a popular book written in 1333 called the Ardashirnama (the Book of Ardashir—an Iranian King), which recounts and embellishes the story of the Book of Esther to emphasize its Jewish owners’ identities as both Iranian and Jewish. The Ardashirnama was written for the Jewish community living in Iran during the time of the Safavid Empire, and the text is not written in Hebrew, but in Judeo-Persian (Persian written in Hebrew characters). This essay explores how the late 17th- and early 18th-century Jewish community celebrated their Jewish–Iranian identity through art and poetry in one illuminated manuscript of the Ardashirnama.

Judeo-Persian text from the Ardashirnama, detail from Queen Esther entertains the king in the presence of courtiers, Ardashirnama, late 17th century, Iran (The Library of the Jewish Theological Seminary)

Jews in Iran and the Ardashirnama

The Jewish community of Iran is an ancient one, and over centuries, this community established a fruitful relationship with their Muslim neighbors. They adjusted to their new cultural environment, and although they reserved their own language, Hebrew, for religious practice, they spoke Persian and read and wrote in Judeo-Persian. They became intimately familiar with and appreciated Iranian art and literature, transcribing the great works of Iranian literature into Hebrew. Beginning in the 14th century, some Jewish poets also wrote new stories, recasting books from the Hebrew Bible, including the Book of Esther, in the form of Iranian poetry. The Ardashirnama is one such book.

The Ardashirnama was written by the Jewish poet Shahin-i Shirazi and it fuses ancient Iranian history with the biblical Book of Esther. Shahin drew on Iran’s great epic, the Shahnama or Book of Kings, and created a national epic that was both Jewish and Iranian.

Left: King Ahasuerus, Shalom Italia, Scroll of Esther, Netherlands, c. 1640–41, hand drawn and manuscript on parchment (Braginsky Collection); center: silver coin (drachm) of Ardashir I, 224–40, minted in Hamadan, Iran (British Museum); Ardashirnama, late 17th century, Iran (Jewish Theological Seminary)

In the great Iranian poems, such as the Shahnama, the legendary heroes were all male. So for the Ardashirnama, Shahin transformed the story of a queen, into the story of a king—the Book of Esther was transformed into the Book of King Ardashir. Ardashir was both a great historical Iranian king (the founder of the Sasanian Empire) and a central protagonist of the Shahnama. By fusing the biblical king Ahasuerus, from the Book of Esther, with Ardashir I in the Ardashirnama, Shahin made the religious story of Queen Esther a national story about the Iranian people.

The growth of Illustrated manuscripts in Isfahan

In the 15th and 16th centuries, artists painted brilliantly illuminated manuscripts for the royal workshop in the Safavid capital city of Tabriz and later the new capital of Isfahan. By the 17th century, as Isfahan emerged as a thriving urban center, artists began to sell their artwork in bazaars and marketplaces (outside of the confines of royal workshops). This broadened the art market and made illustrated manuscripts more affordable for the general population. At the same time, the ruler (Shah ‘Abbas) encouraged various minority populations, including both Jews and Armenians, to move to Isfahan. These changes in Isfahan fostered an environment in which Judeo-Persian manuscripts like the Ardashirnama could be created and valued.

The Ardashirnama that is the focus of this essay is one of only two illuminated Ardashirnama manuscripts that survive, and it is currently in the collection of the Jewish Theological Seminary (JTS). [1] While the scribes (who copied the texts) were Jewish, the identity of the artists who painted the illuminations are entirely unknown. It is possible that they were painted by Jewish artists; but it is more likely that they were created by Muslim artists who adapted familiar Safavid styles to suit commissions from Jewish patrons.

Similar depictions of kingship in the in the Judeo-Persian Ardashirnama (left), and the Iranian epic the Shahnama (right). Left: King Ardashir ascends the throne amidst feasting and rejoicing, Ardashirnama, 17th century, Iran (Jewish Theological Seminary); Right: Bahram Gur and courtiers entertained by Barbad the Musician, from a Book of Kings (Shahnama) manuscript, second half 17th century, Iran, opaque watercolors, ink and gold on paper, 31.4 x 22 cm (Brooklyn Museum)

Iranian kingship and power in the Ardashirnama

Queen Esther entertains Shah (King) Ardashir in the presence of Haman and another courtier, Ardashirnama, late 17th century, Iran (The Library of the Jewish Theological Seminary)

In the JTS Ardashirnama, we see King Ardashir hunting and feasting—activities that conveyed ideals of royal authority in visual terms that contemporaries would have understood. In fact, the manuscript is replete with scenes that communicated the kings’ right to rule. In this way, Esther appears not as just any queen, but as the Queen of Iran alongside her legitimate Iranian king.

In a scene depicting King Ardashir’s ascension to the throne, he is shown seated atop an elaborate wooden throne in a lavishly decorated room. Painted scenes of lush vegetation and jumping hares adorn the wall behind him and his throne is ornamented with delicate scrolling motifs, suggesting carved decoration. A gentleman beneath him offers him a goblet of wine, while musicians play music at his feet, and courtiers dance and celebrate his ascension. Verses from the story appear both above and below the painting. The image that opens this essay similarly depicts a scene of celebration at the Iranian court. Queen Esther is shown entertaining Shah Ardashir as well as two courtiers, including the Shah’s vizier Haman (with his face erased). The painting uses similar conventions to depict a lavish interior—painted scenes on the walls, ornate carpets, and ornamented thrones. The artist of the Ardashirnama renders these festive scenes in the same way that historical and contemporary kings are shown in celebration in Iranian manuscripts.

A 17th-century manuscript of the Shahnama, for example, depicts the Sasanian King Bahram Gur seated on a similarly shaped throne and, like the representation of Ardashir seated on his throne, surrounded by musicians and courtiers, including an attendant bringing him wine. Just as in the Ardashirnama paintings, the image is framed above and below by passages from the story (but here the Persian text is written in Arabic script).

The Ardashirnama and 17th-century anti-Judaism

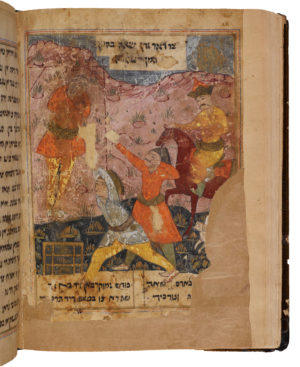

Haman is hung upon the shah’s orders. Ardashirnama, 17th century, Iran (Jewish Theological Seminary)

Although Jews and Muslims mostly coexisted peacefully in Iran for centuries, in the decades just prior to the production of these manuscripts, Jews were required to wear identifying headgear. In the second half of his reign, Shah ‘Abbas I reversed his largely benevolent attitude towards the Jewish community. In 1619–20, he accused the Jews of Isfahan of practicing magic. Under Shah ‘Abbas I, several prominent holy men who would not renounce Judaism were murdered, sacred Jewish books were burned, and many Jews were forced to convert. After a brief period of respite, under Shah ‘Abbas II, in 1656–62, there was another massive persecution of Jews and other minority communities in Iran, including Armenians and Zoroastrians.

After this period of intense persecution, the story of Queen Esther (relating the near extinction of ancient Iran’s Jews) and the Ardashirnama became newly relevant and personal. One image from the manuscript depicts the hanging of Haman, the King’s minister, who plotted to murder the Jews. As in the painting at the opening of the essay, his face is entirely rubbed out. The erasure of the figure by the book’s owners follows the traditional custom to use groggers, or noisemakers, when Haman’s name is mentioned during the annual recitation of the Book of Esther on the holiday of Purim. [2] With each swing of the Purim noisemakers, the name of Haman is blotted out.

As tensions eased, in the ensuing decades, the Ardashirnama and other Judeo-Persian manuscripts continued to be copied and produced within the Jewish communities of Iran. Through the story and paintings of Esther and Ardashir, the Ardashirnama redefined Jewish identity as inseparable from that of the Iranian people. The survival of this rare illuminated manuscript gives visible expression to the Jewish community’s deeply felt Iranian identity, as they adapted Safavid painting to recast Jewish history as intrinsically Iranian history.