The Qur’an is the holy book of the religion of Islam, containing the words of God as revealed to the Prophet Muhammad starting in the year 610. Following the Prophet’s death in 632, these revelations, which had initially been memorized by the early Muslim converts, were fully written out for the first time. At this time they were organized into 114 chapters (called suras in Arabic) that were themselves divided into verses (ayas), and placed in order of decreasing length rather than the order in which they were revealed (except for the first very short opening chapter). Following this codification of the text, Qur’ans have been copied in beautifully produced and lavish manuscripts that reflect the fact that they contain the words of God. The text is written in specially devised scripts, and gold and colored inks are used to enhance the appearance of the pages.

When you encounter pages from a Qur’an, you find much more than just the Arabic text. There are different traditions about where certain verses end, how certain words are pronounced, the intonation to use when reading them aloud, and other such details. As a result, many of the visual features in the text that are classified as decoration were actually introduced into the manuscripts to preserve these specific readings. This essay will help you understand the many marks that appear in historic manuscripts, and how they facilitate the ways the Qur’an is studied, recited, and prayed with.

Frontispieces

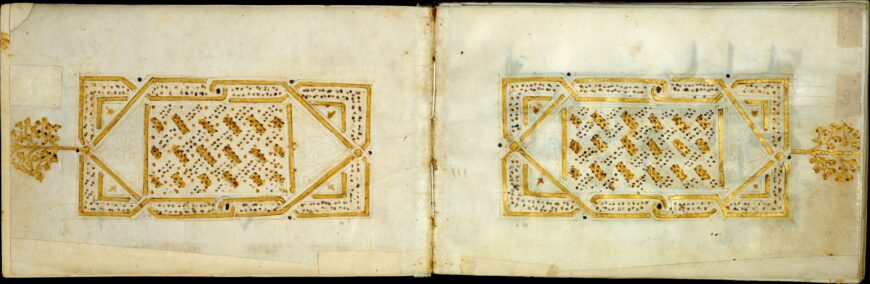

Moving from the front to the back of a manuscript, for instance, you might first encounter a frontispiece. This is either a single page, or two-facing pages, with painted ornament which serves as a decorative entry into the contents.

Frontispiece to volume two of a 30-volume Qur’an, late 9th–early 10th century (Syria or Iraq), ink, opaque watercolor and gold on parchment, 17.1 cm (each page) (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

Many early Qur’ans have frontispieces with geometric or floral illumination, such as this example from the 9th or 10th century which has interlacing gold borders enclosing a geometric, stippled design. Extending into the margins on either side are floral roundels, also in gold.

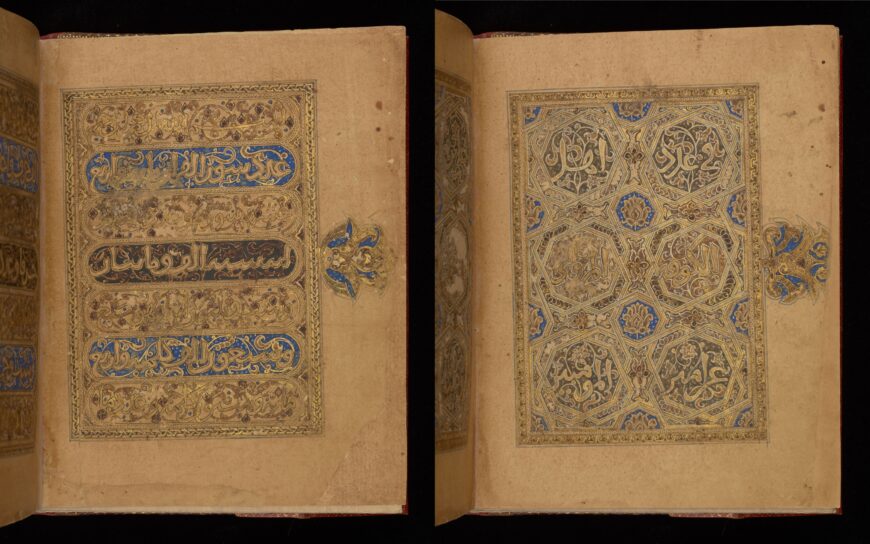

Other frontispieces might also include information about the text itself. The Qur’an copied by Ibn al-Bawwab in Baghdad in 1000–1001 is an important manuscript that serves as an example of what this information might be. It includes three double-page frontispieces, two of which have calligraphy along with the gold, blue, black, and brown decorative motifs.

Left: first frontispiece with script in oblong bands; right: second frontispiece with script in interlacing octagons, Qur’an of Ibn al-Bawwab with chapter, verse, word, letter, vocalization, and diacritic counts, 1000–1001 (Iraq, Baghdad), ink and gold pigment on paper, 18.3 x 14.5 cm (Chester Beatty Library, Dublin, Is 1431, folios 6 verso and 7 verso)

In the first frontispiece, the script is arranged in oblong bands while in the second it is set within interlacing octagons. The calligraphy specifies the number of chapters, verses, words, letters, and diacritical marks in this volume of the Qur’an. This accords to an accounting approved by ‘Ali ibn Abi Talib (an early convert and a son-in-law of the Prophet Muhammad). Ibn al-Bawwab would have included this information to certify that he had copied exactly a particular reading of the Qur’an, in its entirety, and without error. This last part was important because it’s always possible, when copying a text by hand, for words or phrases to be accidentally skipped or repeated.

Chapter headings

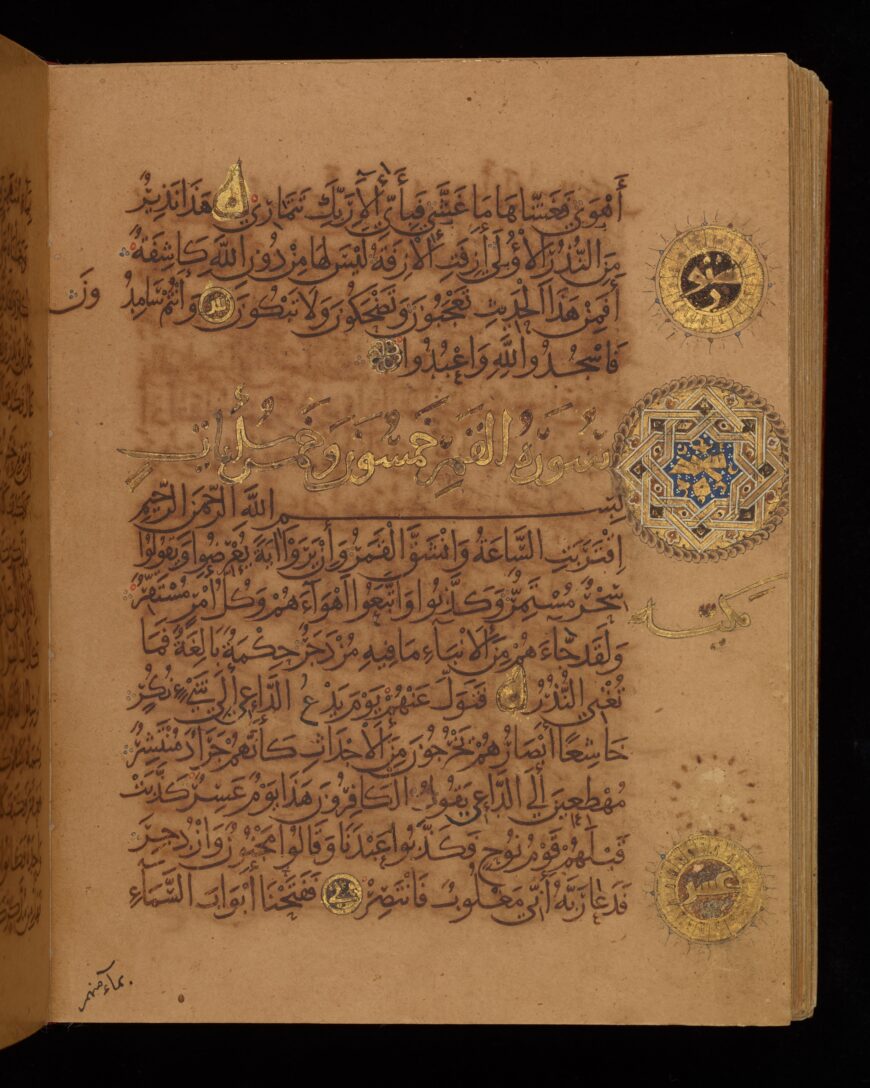

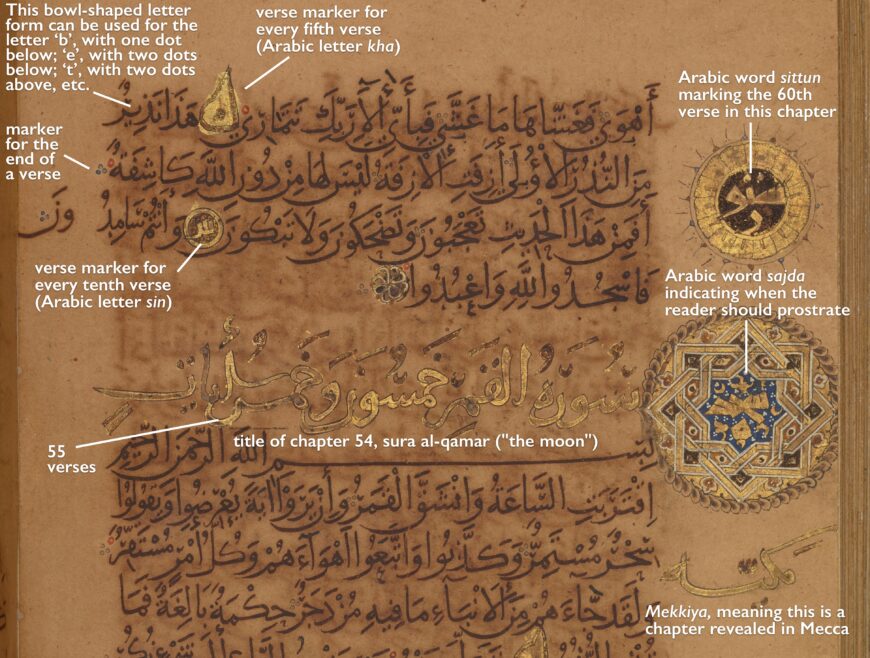

The text following the frontispiece is organized by chapter, with the chapter names written in a different script from the main text. On this page, the title of chapter 54, sura al-qamar (“the moon”), appears on the fifth line from the top, in a gold ink also different from that used for the Qur’anic text.

Folio from the Qur’an of Ibn al-Bawwab with Sura 53 (al-Najm, “The Star”), verse 53 and Sura 54 (al-Qamar, “The Moon”), verses 1–11, 1000–1001 (Iraq, Baghdad), ink and gold pigment on paper, 18.3 x 14.5 cm

(Chester Beatty Library, Dublin, Is 1431, folio 243 verso)

Since the chapters names were applied later to each revelation (usually taking a word that features prominently within it), the change in script makes it clear that the titles are not part of God’s words. This heading also includes the number of verses in the sura (in this case, 55), and the place where it was revealed to Muhammad—either Mecca or Medina (this verse was revealed in Mecca, as indicated by the word “Meccan” in the margin).

Folio from the Qur’an of Ibn al-Bawwab with Sura 53 (al-Najm, “The Star”), verse 53 and Sura 54 (al-Qamar, “The Moon”), verses 1–11, 1000–1001 (Iraq, Baghdad), ink and gold pigment on paper 18.3 x 14.5 cm (Chester Beatty Library, Dublin, Is 1431, folio 243 verso)

Diacritics and vocalizations

In Arabic, short vowels do not have their own characters, and some consonants share character forms only distinguished with the addition of diacritics (the dots placed above or below these forms to create different letters). This copy of the Qur’an is distinguished by the clear and consistent use of diacritic and vocalization marks, which did not always appear in earlier Qur’ans. This is an important feature since the Qur’an, whose name itself means “recite,” is taught and memorized by reading aloud, following rules about the pronunciation, style, tone and intonation by which it is voiced. The Qur’an is also recited as part of daily prayers, during sermons and other ceremonies, and is experienced by sound as much as by sight. The inclusion of these marks therefore not only help avoid confusion about which letter has been written, but also assist someone reciting the Qur’an aloud to pronounce the words correctly according to the reading by which the text has been copied.

Verse markers

This page also includes markings for the ends of verses. These kinds of markings appear in many Qur’an manuscripts and can take different forms, ranging from small gold circles to rosettes or the motifs here, of the three dots arranged in a triangle (one such marking can be seen at the left side of the second line).

At the end of every fifth verse the dots are replaced with a golden letter kha, as seen on the top line.

Tenth verses are marked in a more elaborate way: within the text is a gold circle inscribed with a letter that represents the number of verses reached, while another gold roundel in the margin includes that number written out in words. This kind of mark was included because variant readings can break verses in different locations; the insertion of the verse marker would therefore make it clear which reading is used in a given manuscript. It also helps the reader keep a count of the verses, both to certify the integrity of the text that has been copied, and also to track how many verses have been read on a particular day, since sometimes worshippers will read the text in equal parts over the course of a week or a month.

Markers for prostration

One last type of mark found on this page indicates where a person reading or reciting the Qur’an should prostrate (bend down and touch the forehead to the ground). Here it is an illuminated circle to the right of the chapter heading; at its center is a golden star-shape around the word sajda (prostrate). There are either fourteen or fifteen verses for which prostration is indicated (depending on different beliefs), and the act reflects the person’s humility through his or her willingness to prostrate in front of God.

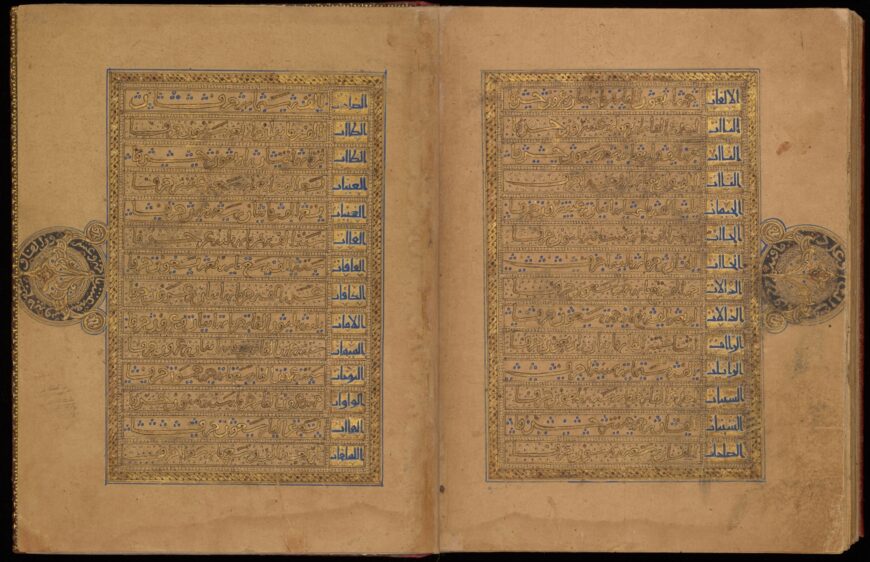

Ending illumination from the Qur’an of Ibn al-Bawwab with letter counts, 1000–1001 (Iraq, Baghdad), ink and gold pigment on paper, 18.3 x 14.5 cm (Chester Beatty Library, Dublin, Is 1431, folios 285 verso–286 recto)

Finispieces

Finally, at the end of the text, in what is called a finispiece, some Qur’ans include tables that provide the number of times each letter in the alphabet appears. These tables serve again to certify the completeness and correctness of the text that has been copied. The Ibn al-Bawwab Qur’an includes just such an accounting on a set of illuminated folios that concludes the manuscript; on the right side of each table is the name of the letter, and to left is written the number of its occurrences.

Division into volumes

One last development to note are the methods for separating the Qur’anic text into sections in order to facilitate its reading over specific periods of time. In these cases, the text would be divided in nearly equal parts that might be read during the course of a week (creating seven parts called manazil, plural of manzil) or a month (creating 30 parts called ajza’, plural of juz’). The thirtieths might also be sub-divided into a half (nisf), a fourth (rub‘), and even sixtieths (ahzab, plural of hizb). In a single-volume Qur’an, these divisions in the text could be indicated with illuminations in the margins. Alternatively, the sections could be bound separately; in especially elaborate productions, each of these volumes might be given their own frontis- and finispieces.

These interventions into the Arabic text were devised over many centuries in response to the changing needs of the numerous Muslim communities. As the text of the Qur’an was written, as the initially small group of Muslims spread into non-Arabic speaking areas, as scholars developed variant readings, and as rituals involving the Qur’an developed, calligraphers and illuminators responded with a range of visual devices to help and support with readings of the text, but in beautiful and eye-pleasing ways that corresponded to the sanctity of the text.

Additional resources

Colin F. Baker, “Illumination of the Qur’an”