Mosque-Madrasa of Sultan Hassan and the al-Rifa’i Mosque, seen from the Citadel, Cairo (photo: Ahmed.magdy.88, CC BY-SA 4.0)

For many people, Cairo, the modern capital of Egypt, recalls a bustling metropolis with museums full of ancient art. However, the origins of the city are much more recent. Since its founding in 969 by the Fatimids, Cairo has been the seat of several important medieval dynasties, reaching its zenith under the Mamluks who left behind a staggering number of impressive public and pious foundations. These foundations were endowed for the public to use—for example, mosques, madrasas, khanqāh, sabīl-kuttāb (places of worship, schools, and fountains) and greatly influenced the urban and architectural character of the city. As a result, Cairo flourished as a cultural, political, and social capital in the region for centuries, including as a modern and industrial city in the 19th century. Today, more than 400 extant registered historic monuments survive tucked away amid the modern urban sprawl, which are complemented by richly decorated artifacts found both in situ and on display in the Museum of Islamic Art (MIA) in Cairo.

Islamic Museum, Cairo (photo: Gérard Ducher, CC BY-SA 2.5)

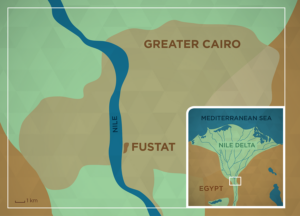

Map showing the location of al-Fusṭāṭ and Cairo (AramcoWorld)

What we call Cairo today succeeds several earlier cities in the area. The first was al-Fusṭāṭ, a military encampment founded after the Arab/Muslim conquest of Egypt in 641 by general ʿAmr ibn al-ʿĀṣ. Al-Fusṭāṭ is just south of modern Cairo, and was strategically located parallel to a canal dug by the Roman Emperor Trajan that linked the Nile to the Red Sea. This provided a direct trade route between the Mediterranean Sea and Asia.

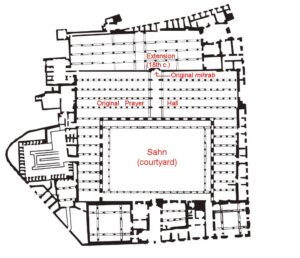

In addition to his successful military campaigns, general ʿAmr also built the hypostyle Mosque of ʿAmr, the first in Africa in the newly founded capital (nothing survives of the original 7th century building). Over time, al-Fusṭāṭ evolved from an encampment to a town and eventually an important commercial and political center. Even when the Abbāsid governors built a new administrative capital to the north called al-ʿAskar in 750, al-Fusṭāṭ continued to grow into a major metropolis.

The founding of Cairo

The Fatimids rose to power in the early 10th century in Ifrīqiya. They were ambitious and sought to expand their empire east and rule over the Islamic world. To do this though, they would first have to defeat the Abbāsids at their capital in Baghdad. The first step in this process was the conquest of Egypt. After launching two failed invasions, they succeeded in 969 under the leadership of caliph al-Muʿizz and his general Jawhar al-Siqilī.

The Fatimids then needed a new imperial city and selected a site located in the desert to the north of the previous capitals and beyond the reach of the Nile floods. This new capital was named Cairo (derived from the Arabic al-Qāhira, The Victorious). The site was further protected by the limestone Muqaṭṭam Hills on the east, the Roman canal on the west (re-excavated in 643–644) and was fortified first by brick walls.

Most Egyptian Muslims remained Sunni and were, therefore, separated from the Fatimids by religious and urban barriers: the caliph, their families, and entourage lived in the walled city, while the masses remained in al-Fusṭāṭ to the south. The Persian poet and traveler Nāṣir-i Khusraw lived in Egypt from 1047 to 1050. In the Safar-nāma, an account of his travels and pilgrimage to Mecca, he described the Cairo and al-Fusṭāṭ of the 11th century in detail. While Cairo was spacious, al-Fusṭāṭ, was a much denser city with crowded streets and tightly packed houses; it was full of shops, markets and lanes lit with lamps continuously since natural light hardly illuminated the streets. The area linking Cairo and al-Fusṭāṭ was full of orchards, gardens, and ponds that were formed by the annual inundation of the Nile.

Luster bowl, 11th century (Fatimid) (Museum of Islamic Art, Cairo; photo: Richard Mortel, CC BY 2.0)

Cairo had considerable attraction for artisans and craftsmen from around the Islamic world. International trade and economic activity are evidence of the prosperity of the time, where merchants traveled in search of quality goods.

Trade occurred in the markets of Cairo, while the goods were manufactured in al-Fusṭāṭ. During the Fatimid period, al-Fusṭāṭ was a major center for the manufacture of luster-painted glass and pottery; textiles; and carved rock-crystal, ivory, and wood.

Map, Cairo, early Fatimid period 969–1073, from Irene A. Bierman, Writing Signs: The Fatimid Public Text (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998)

The monuments of Cairo

Cairo had a rectangular plan that ran parallel to the canal. The city walls were lined with several defensive gates and the main thoroughfare, al-Qaṣaba, ran north-south.

At the center of Cairo stood two sumptuously decorated palaces: the Great Eastern Palace and Smaller Western Palace opposite it. Both overlooked Bayn al-Qaṣrāyn, a wide-open parade ground that became the setting of great events and lavish court ceremonies. The two palaces were an extraordinary campus of buildings that included courts, mosques, and a burial ground; they were surrounded by open spaces, orchards, and beautiful gardens.

Nothing survives from the palaces except for written descriptions left by contemporaneous and near-contemporaneous historians and travelers, although richly carved architectural decorations were reused in later Ayyubid and Mamluk foundations built on the ruins of the palaces. These architectural elements, many of which are in the collection of the MIA, are a testimony to the grandeur and luxuriousness of the palaces.

Wooden panel decorated with human, animal and floral decorations from the palaces of the Fatimid caliphs in al-Mu’izz street between Bāb Zuwayla and Bāb al-Futūh gates, 11th century (Museum of Islamic Art, Cairo)

Over the course of their two-century rule, the Fatimids invested heavily in Cairo; although today we are limited to the few surviving mosques, city gates, and shrines. Though few in number, these monuments show us the great creativity of this period, and the reason for its long-lasting influence on later dynasties.

Mihrab (prayer niche), the gold is a later addition, al-Azhar Mosque, Cairo, 970 (photo: R Prazeres, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Their first mosque, al-Azhar was built in 970 in southern Cairo (so as not to encroach on Bayn al-Qaṣrāyn which dominated the city). The first prayer was held there in 972, and it acquired the status of a college in 989. Shīʿa theology was taught at al-Azhar and it became an important center of learning. The original hypostyle plan (built by Jawhar al-Siqilī—the general who with caliph al-Muʿizz, had captured Egypt), consisted of a sanctuary with five aisles that ran parallel to the qibla wall and bisected by a wider and higher transverse aisle that led to an intricately carved directional prayer niche (mihrab), that faced Mecca. What you see of al-Azhar today is the outcome of later additions.

Projecting portal, façade, Mosque of al-Ḥakīm, Cairo, 990 (photo: Iman R. Abdulfattah, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

In 990, caliph al-Ḥakīm commissioned a second major mosque that was initially located outside the city walls, then absorbed at the end of the 11th century when the walls were rebuilt.

Bāb Zuwayla gate, Cairo (photo: JMCC1, CC BY-SA 3.0)

The Mosque of al-Ḥakīm’s façade, projecting monumental portal, and corner minarets are all clad in stone, marking the beginning of a newly cultivated taste for this medium. Interestingly, this configuration was inspired by the Great Mosque of Mahdiyya (916) in the former Fatimid capital in Ifrīqiya (which in turn harkens back to Roman triumphal arches like the outstanding example in Timgad).

By the end of 11th century, urban growth and external threats hastened the need to replace the brick walls constructed by Jawhar al-Siqilī. Badr al-Jamālī, the Armenian vizier of caliph al-Mustanṣir, rebuilt them in stone using master stonemasons from Edessa and Syria (it was not unusual for prosperous courts to seek exceptional craftsmen from further afield).

Three gates survive today (Bāb al-Futūh and Bāb al-Naṣr were built on the north walls in 1087, and the Bāb Zuwayla was built on the south walls in 1092). From the towers of the latter rise the elaborately carved minarets of the later Mamluk Mosque of al-Muʾayyad Shaykh, built 1415–22.

Perhaps the most important mosque of this period is al-Aqmar, built in 1125. Of particular significance is the way that the façade is aligned with the main thoroughfare of al-Qaṣaba, but the floor plan shifts to respect prayer orientation towards Mecca which is a requirement in any mosque. Such contorted plans demonstrate that pious foundations could accommodate irregular plots of land in the expanding imperial capital.

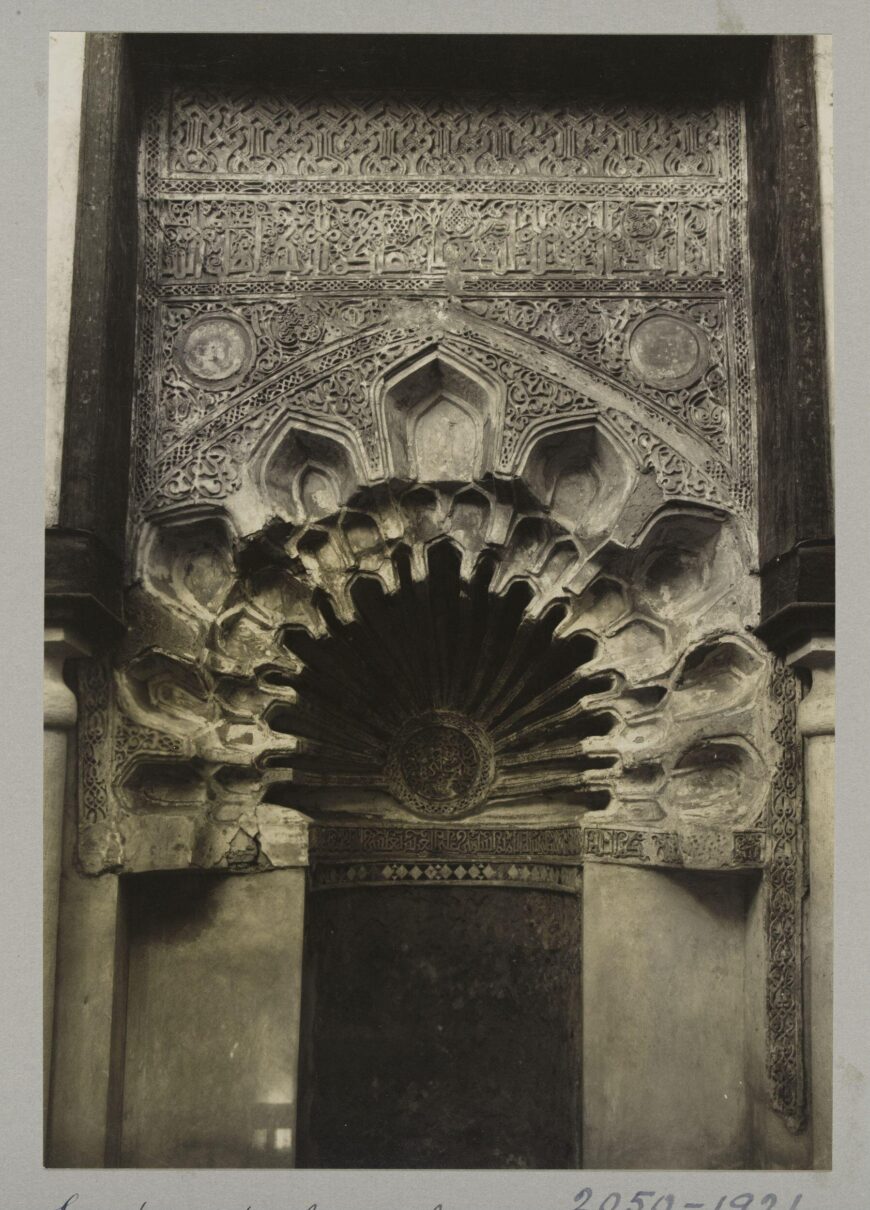

Mihrab, Shrine of Sayyida Ruqayya, Cairo, 1133, photographed by Professor Sir K.A.C. Creswell (Victoria and Albert Museum, London)

With the continued growth of Cairo, another important genre of buildings emerged during the end of the Fatimid period. A series of shrines dedicated to members of the Prophet’s family (ahl al-bayt) were built outside of the city walls as significant places of prayer and visitation (ziyāra). These shrines are still used as oratories where people make vows and pray for the deceased’s intercession. One of the most impressive Fatimid shrines is dedicated to Sayyida Ruqayya, a member of the Prophet’s family and patron saint of Cairo. It is still used as an oratory today, and is most known for its beautifully carved stucco mihrab.

Decline of the Fatimid caliphate

At its peak, Fatimid Cairo was the center of an empire with a geographic expanse that included parts of North Africa, Sicily, Palestine, Jordan, Lebanon, Syria, the Hijaz, and Yemen. However, by the late 11th and early 12th century, internal strife, drought, and famine in Egypt led to the decline of the caliphate. In 1168, al-Fusṭāṭ suffered great damage in a fire ordered by the Fatimid vizier to thwart the potential advances of the Crusaders. This episode ushered in two major changes: the Ayyubids overthrew the Fatimids in 1171 and ruled Egypt and the eastern Mediterranean from Cairo; and they erected new stone fortification walls that now enclosed Cairo and al-Fusṭāṭ.