Bahram Gur Fights the Karg (Horned Wolf), from the Great Mongol Shahnama, c. 1330-40, Iran, ink, colors, gold, and silver on paper, folio 41.5 x 30 cm (Harvard Art Museums/Arthur M. Sackler Museum)

As Bahram Gur’s men faced the Karg, a monstrous horned wolf that had been terrorizing the countryside, they cried, “Your majesty, this is beyond any man’s courage…tell Shangal this can’t be done….”

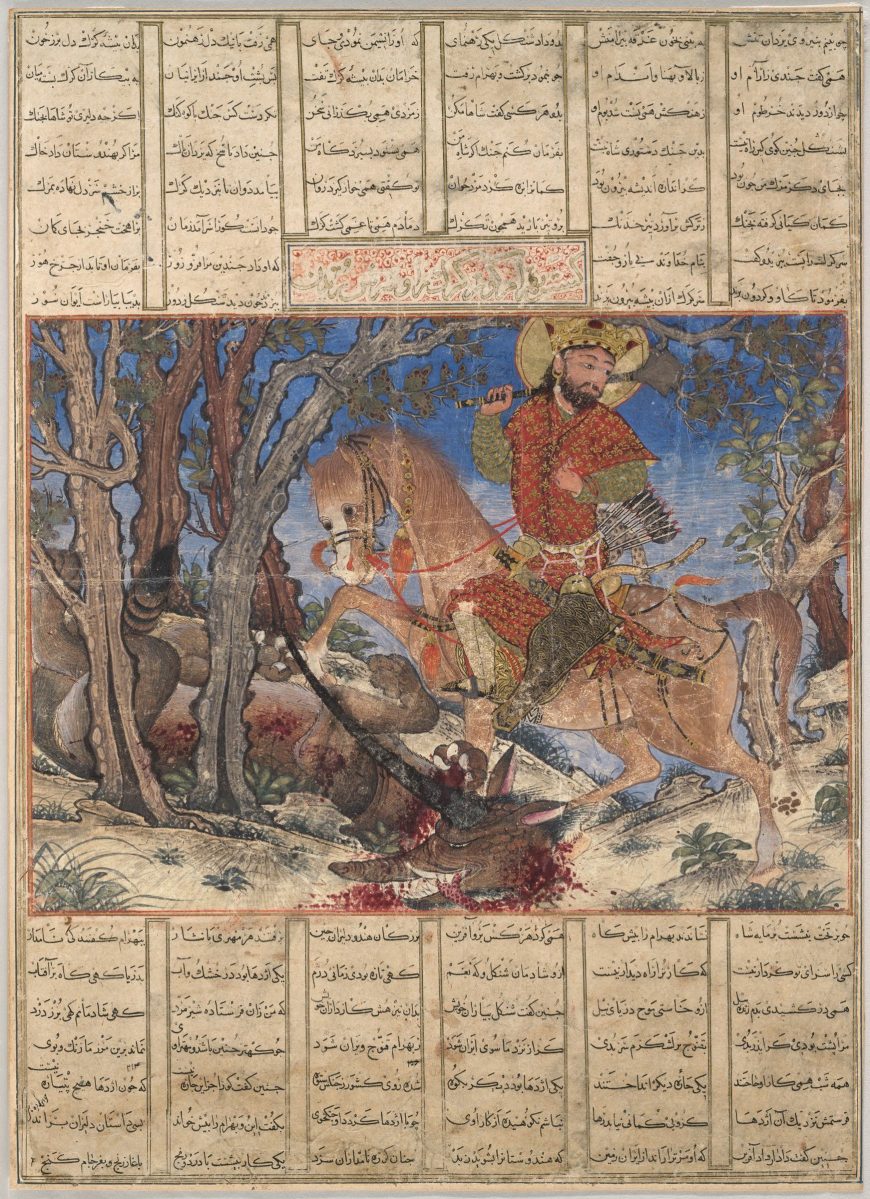

Bahram Gur Fights the Karg is a book illumination depicting one of the many stories from the Shahnama, the Persian Book of Kings. Though this particular image was painted in the fourteenth century by artists in the Mongol court in Persia (present-day Iran), the text of the Shahnama was composed by a poet named Firdawsi four hundred years earlier, around 1000 C.E. The Shahnama incorporates many older stories once told orally, chronicling the history of Persia before the arrival of Islam and celebrating the glories of the Persian past and its ancient heroes. The Shahnama is, in fact, still taught in Iranian schools today, and is considered to be Iran’s national epic—to know or recite the stories of the Shahnama is to express pride in the country’s glorious past. The illustration Bahram Gur Fights the Karg depicts one such story of the brave deeds of a Persian king, Bahram Gur, who singlehandedly defeated the monstrous Karg (horned wolf). It is much more than just an exciting tale, however; the Mongol artists who created this work were fulfilling their patrons’ strong desire to identify with the noble, virtuous, and powerful warrior-kings of ancient Persia.

Who was Bahram Gur and what is a Karg?

Plate with a hunting scene from the tale of Bahram Gur and Azadeh , c. 5th century, Sasanian, silver, mercury gilding, 20.1 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

Bahram V was a king of the Sasanian empire that ruled Persia from the third to the seventh century, just prior to the arrival of Islam. His nickname, Bahram Gur, refers to a “gur” or onager—a type of wild ass which is one of the world’s fastest-running mammals. The word “gur” may also mean “swift.” He was known as a great hunter of onagers, a favorite game animal in ancient Iran, and he was renowned for his talents in warfare, chivalry, and romance. On a trip to India, according to the Shahnama, the king of India, a ruler named Shangal, recognized Bahram Gur’s abilities and sought his help in ridding the Indian countryside of the frightening and fierce Karg.

Bahram Gur Fights the Karg (Horned Wolf) (detail), from the Great Mongol Shahnama, c. 1330-40, Iran, ink, colors, gold, and silver on paper, folio 41.5 x 30 cm (Harvard Art Museums/Arthur M. Sackler Museum)

Some translations of Firdawsi’s work describe the Karg as a rhinoceros, some as a wolf, and some, as we find here in Bahram Gur Fights the Karg, as a combination of the two—a ferocious horned wolf. When Bahram Gur and his men found the lair and saw the beast, his men beseeched, “Your majesty, this is beyond any man’s courage…tell Shangal this can’t be done….” The hero, of course, went forward alone, first using his bow to weaken the Karg with arrows, then using his blade to cut off the Karg’s head to present to Shangal.

The Mongol court and the art of the book

The Sasanian empire fell in the seventh century, and it was not until well after this that the Mongols invaded Persia. They came from the eastern Asian plains, where open grasslands had encouraged a nomadic lifestyle of herding, horsemanship, and fierce warfare. They first became a serious force under the leadership of Genghis Khan in the early thirteenth century, and later, under his grandson Hulagu, the Mongols expanded their reach all the way to the Mediterranean.

Map of the Ilkhanid state, 1256-1353 (map: Ahmed Hafez)

Settled in Persia, the Mongols fostered the growth of cosmopolitan cities with rich courts and wealthy patrons who encouraged the arts to flourish. The rule of Hulagu’s dynasty, which lasted until 1335, is commonly known as the Ilkhanid period. Book illustration thrived under the Ilkhanids and became a major art form for both religious and secular texts. Since the Mongols began as, and largely remained, nomadic peoples (moving from place to place during the year to satisfy the needs of their herds), artworks tended to be small and portable. Their long nomadic history also meant that the Mongols developed strong oral traditions of storytelling, which gave them an appreciation for narrative art—especially manuscripts with paintings to accompany the stories. Illustrated manuscripts were also prestige items, created in very sumptuous formats suitable for kings, princes, and members of the court.

It was within this environment of lavish artistic book production that the manuscript depicting Bahram Gur Fights the Karg was created, probably in a court workshop. The artists who crafted it used silver and gold accents over ink and opaque watercolor. While we do not know the name of the patron, scholars suggest that it may have been the court vizier, a high-ranking official. The full page, or folio, is relatively large for a hand painted book, and because of its size, the manuscript is also referred to as the Great Mongol Shahnama. It was most likely a prestige item intended to express the owner’s power and wealth, and it is the most luxurious of all the Ilkhanid painted books that survive. In its original form, scholars believe this complete manuscript probably comprised about 280 folios (pages) with 190 illustrations painted by several different artists, bound into two separate volumes. Today, however, only 57 folios are known to have survived. Like many other manuscripts, the Great Mongol Shahnama was taken apart by an early twentieth-century art dealer so that the pages could be sold separately.

The illumination as a stylistic blend

Six Horses, 13th–14th century, China, ink and color on paper, 47.1 x 647.1 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

This manuscript was likely completed at the Mongol court in Tabriz, a rich and cosmopolitan urban center (in what is today northern Iran). By the time the book was produced, the Mongols had settled into their role as refined rulers with international contacts, and their lands were secure enough to ensure the safe exchange of both goods and ideas throughout the empire. The increased availability of paper, invented in China in the eighth century, also encouraged the diffusion of artistic ideas. Consequently, Ilkhanid art had an international flavor. Landscape elements, for instance, often show influences from China, incorporating motifs seen on imported Chinese scrolls (above) and ceramics. In Bahram Gur Fights the Karg, the worn and twisted trees, overlapping forms that create spatial recession, rapidly brushed foreground vegetation, and a taste for asymmetry all suggest eastern Asian influences.

Bahram Gur Fights the Karg (Horned Wolf) (detail), from the Great Mongol Shahnama, c. 1330-40, Iran, ink, colors, gold, and silver on paper, folio 41.5 x 30 cm (Harvard Art Museums/Arthur M. Sackler Museum)

Local influences are also apparent: Persia had a long artistic tradition of depicting heroes, kings, and hunters riding horses over slain opponents. Bahram Gur is depicted in this tradition. Shown on horseback, he wears kingly garb, with a golden crown, luxurious garment, and an elegant gold and pearl earring visible in his right ear. But he is also clearly a warrior, holding a mace over his shoulder, and with a bow, sword, and arrows covered in a leopard skin hanging from his waist.

Bahram Gur Fights the Karg (Horned Wolf), from the Great Mongol Shahnama, c. 1330-40, Iran, ink, colors, gold, and silver on paper, folio 41.5 x 30 cm (Harvard Art Museums/Arthur M. Sackler Museum)

The result is a dynamic, energy-filled image with a monumental figure almost bursting out of the frame: Bahram Gur is cut off slightly at the top, trees and landscape details are truncated at the edges, and the horse is captured in mid-motion with one leg raised above the Karg. The Karg’s head, very close to the viewer, is centrally placed and dripping blood, while the splayed length of the Karg’s battered body pulls the viewer’s eye toward the left. The focus returns to the hero, however, because a visual circuit is created around him. Our eyes travel along the horn of the Karg, to the continuous arc of the tree branch, and up to Bahram Gur, whose glance leads our eyes back down across the vegetation and the body of his horse.

The page surrounding Bahram Gur Fights the Karg is covered with calligraphy, but we do not know what originally appeared on the page adjoining the painting because the book pages are dispersed today. Calligraphy is the most highly regarded form of Islamic art, and it can be highly stylized, showing off an artist’s personal flare and skill. Ideals of beauty in Islamic culture draw on calligraphy’s inherent harmony and balance, spacing, proportion and compositional evenness on the page, and these aesthetic values are also visible in the painting style of the Great Mongol Shahnama.

Calligraphy (detail), Bahram Gur Fights the Karg (Horned Wolf), from the Great Mongol Shahnama, c. 1330-40, Iran, ink, colors, gold, and silver on paper, folio 41.5 x 30 cm (Harvard Art Museums/Arthur M. Sackler Museum)

Old heroes for a new regime

There is a tradition within Islam that strongly discourages the visual representation of human or animal figures. In practice, however, figurative representations can very often be found in secular and private Islamic contexts, such as the Ilkhanid court, where it was acceptable—even desirable—to create splendid figurative artworks for private consumption.

This was true of the Shahnama, which was a favorite subject at the Mongol court, eagerly enjoyed by wealthy and sophisticated courtiers. The painters who illustrated the Shahnama were drawn to dramatic subjects such as battles or encounters with astonishing beasts such as the Karg. However, images like Bahram Gur Fights the Karg were not just meant as illustrations of simple, enjoyable fairy tales, but contained deeper meaning and significance for the Mongol nobility. Here, Bahram Gur symbolizes just rule and civilized society triumphing over chaos and disorder, represented by the Karg. In simple terms, this means good defeating evil, but it also implies that a good and stable social order is based upon kingship, and that warrior-kings like Bahram Gur are moral and courageous models to be emulated by the readers of the book. The Shahnama therefore also provided a teaching tool, subtly incorporating moral stories and illustrating desirable behaviors for future kings and nobles.

Bahram Gur Fights the Karg (Horned Wolf) (detail), from the Great Mongol Shahnama, c. 1330-40, Iran, ink, colors, gold, and silver on paper, folio 41.5 x 30 cm (Harvard Art Museums/Arthur M. Sackler Museum)

Many scholars also believe that the new Mongol rulers in Persia wanted to link themselves to the great heroes and kings of Persia’s past, a link which would enhance their authority. The Mongols and the ancient Persians had a shared respect for the manly arts of fighting, hunting, feasting, and courtship, and it is not a coincidence that Bahram Gur rides a horse as he defeats the Karg: the story is Persian, but the hero is shown as a great Mongol horseman.

The Shahnama is filled with magical tales of courtly life, including kings and heroes who fight, hunt, and live life to the fullest, as illustrated in the story of Bahram Gur Fights the Karg. But the Shahnama is also somewhat fatalistic, presenting a hostile world filled with fierce foes like the Karg. The book even ends with the defeat of the Persians by the Arabs. The stories, however, teach about the importance of courage and ethics while traveling through such a threatening world, and they provide guidance for readers confronting questions about death, love, honor and just rule.

Additional Resources

Bahram Gur Fights the Karg (Horned Wolf) at the Harvard Art Museums, Arthur M. Sackler Museum

Sheila Blair and Jonathan Bloom, Art and Architecture of Islam: 1250–1800 (New Haven, CT, 1994).

Jonathan Bloom and Sheila Blair, Islam: A Thousand Years of Faith and Power (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2002).

Abolqasem Ferdowsi, Shahnameh: The Persian Book of Kings (New York: Viking Penguin, 2006).

Gene Garthwaite, The Persians (Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2007).

Robert Irwin, Islamic Art in Context: Art, Architecture and the Literary World (New York and Upper Saddle River NJ: Prentice Hall & Abrams, 1997).

Cite this page as: Jayne Yantz, “Bahram Gur Fights the Karg (Horned Wolf),” in Smarthistory, January 15, 2017, http://smarthistory.org/bahram-gur-fights-the-karg/.