More than one thousand years ago, a ship on its journey home to West Asia from Tang China sank off the coast of the island of Sumatra (today part of the modern nation state of Indonesia). In the 9th century, this region was the center of a maritime power known as Srivijaya. The ship’s cargo consisted primarily of Chinese ceramics. However, it contained other precious objects in gold, silver, and bronze as well as spices packed into storage jars. Known as the Belitung Shipwreck, it reveals a unique view of the global trade and artistic interchange in the Indian Ocean World during the 9th century.

The Indian Ocean World

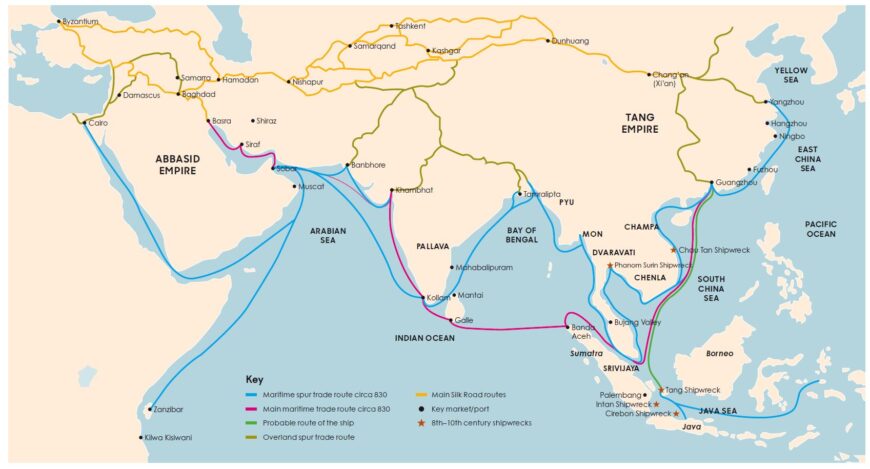

The Indian Ocean World is a term used in scholarship to define a broad geographical area that re-orients our perspective to the seas as opposed to the land. [1] It stretches from the East coast of Africa to the South China Sea. The landmass of India divides it into two halves. To the west lies the Arabian Sea, the Gulf, and the Red Sea. They act as gateways to Africa and the Islamic cultures of West Asia. To the east lie the peninsulas and islands of Southeast Asia. Traversing these, one enters the South China Sea, beyond which lies the vastness of the Pacific Ocean. From the 7th century onwards, these maritime routes were well known to Arab, Persian, and Malay sailors. Sophisticated networks stretching along ports and coastal cities developed, facilitating trade and travel over vast distances. It is within this interconnected Indian Ocean World that we can understand the significance of the Belitung Shipwreck.

Ceramics from the Belitung wreck lie undisturbed on the seabed (photo: courtesy Michael Flecker, CC BY-NC-SA)

The ship and its recovery

In 1998 local fisherman diving for sea cucumbers off the coast of Belitung Island, Sumatra, Indonesia came across a mound on the seafloor. Taking a closer look, they began to uncover well preserved Chinese ceramic bowls and soon realized that they had discovered a shipwreck. Word spread quickly and looting of the site began. [2] However, the Indonesian government soon secured the site and granted a commercial salvage license to a German company, Seabed Explorations, to recover the wreck. It was subsequently named the Belitung Shipwreck after its findspot. Over the course of two seasons, the salvagers recovered over 60,000 ceramics as well as items in gold, silver, and bronze. [3]

While the commercial salvage of the wreck led to its speedy recovery and protected it from looting, the company only engaged archaeologists to record details of the site, the ship, and its contents during the second round of recovery work in April 1999. This led to the recording of important information, such as the construction method of the ship. However, it was nowhere near as comprehensive as it would have been if archaeological methods had been applied from the start. Many archaeologists argue that commercial involvement compromises the documentation and retrieval of historical data from wreck sites, since the pursuit of profit may take precedence over preservation and research. However, underwater archaeological excavations require highly specialized professionals and are prohibitively expensive, and this was not a realistic option for Indonesia in 1998. [4] While the cargo was successfully recovered and acquired by the Singapore government and put on display at the Asian Civilisations Museum, much contextual information has been lost. Salvage is thus at best a very imperfect solution to the intractable problem of safeguarding and recovering shipwrecks at high risk of being looted.

And what of the wreck itself? We know from its construction technique—it was sewn together and did not use nails or dowels—that it was built in West Asia of timbers sourced in Africa. It most likely came from somewhere in the Abbasid Caliphate centered in modern-day Iran and Iraq. [5] A single bowl in the cargo was engraved with Chinese characters which have been read as Baoli ernian qiyue shiluiri, that is, the 16th day of the 7th month of the second year of Baoli era (the reign of the Jingzong Emperor), or 16 July 826 C.E. [6] It is highly likely that the ship set sail shortly after this date. Radiocarbon dating of wood samples recovered from the hull and stylistic comparisons of the Chinese ceramics on board also point to a 9th century date for the ship.

![Dish with incised floral lozenge, c. 830s (China, probably Gongyi [Gongxian] kilns), stoneware (courtesy Asian Civilisations Museum, CC BY-NC-SA)](https://smarthistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/fig.-4-870x489.jpg)

Dish with incised floral lozenge, c. 830s (China, probably Gongyi [Gongxian] kilns), stoneware (courtesy Asian Civilisations Museum, CC BY-NC-SA)

The cargo and the market

The Belitung wreck’s cargo paints a picture of a highly interconnected Indian Ocean World. Many of the Chinese ceramics it carried were tailored for the West Asian Market. This resulted in hybrid objects that combined elements of both Chinese and Islamic art and design. The most common of these was the Iranian/West Asian lozenge and palmette design. It is found primarily on green-splashed ceramics in the cargo. Fired at the Gongyi (Gongxian) kilns in Henan Province, northern China, they were produced by first applying a white slip to the body of the object over which a clear glaze was then added. [7] Finally splashes of green copper glaze were added in a rather freeform fashion, all of which would have required multiple firings in a kiln. In some cases, a lozenge and palmette design was added in incised decoration. These designs begin to be produced in the 6th century, hitting the peak of their popularity in the 9th century.

Given that there is little to no evidence of these ceramics being found in archaeological sites in China (apart from port locations such as Yangzhou and Ningbo), these ceramics appear to have been made purely for export. Discoveries of these ceramics at the 9th century Abbasid capital of Samarra in modern day Iraq, and Siraf and Nishapur in modern day Iran further supports this theory. [8]

![Ewer, c. 830s (China, probably Gongyi [Gongxian] kilns) stoneware (Courtesy Asian Civilisations Museum, CC BY-NC-SA)](https://smarthistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/fig.-5-870x902.jpg)

Ewer, c. 830s (China, probably Gongyi [Gongxian] kilns) stoneware (Courtesy Asian Civilisations Museum, CC BY-NC-SA)

![Blue-and-white dish, c. 830s (China, Gongyi [Gongxian] kilns) stoneware (Courtesy Asian Civilisations Museum, CC BY-NC-SA)](https://smarthistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/fig.-6-870x489.jpg)

Blue-and-white dish, c. 830s (China, Gongyi [Gongxian] kilns) stoneware (Courtesy Asian Civilisations Museum, CC BY-NC-SA)

Conclusion: an interconnected world

The Belitung Wreck provides some of the clearest evidence to illustrate how interconnected the Indian Ocean World was in the 9th century. People from West, South, and Southeast Asia and China were carried by monsoon winds along a network of ports and harbors. They took with them their products, ideas, arts, and designs, all of which left an indelible mark on the cultures that made up this thriving maritime world.

Notes:

[1] Edward A. Alpers, The Indian ocean in world history (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014), pp. 5–7.

[2] Natali Pearson, Belitung: The Afterlives of a Shipwreck (Honolulu: University of Hawaiʻi Press, 2023), pp. 58–61.

[3] Stephen A. Murphy, “Asia in the ninth century: the context of the Tang Shipwreck,” The Tang Shipwreck: art and exchange in the 9th century, edited by Alan Chong and Stephen A. Murphy (Singapore: Asian Civilisations Museum, 2017), p. 19.

[4] Pearson (2023), pp. 69–71.

[5] Michael Flecker, “The origin of the Tang Shipwreck: A look at its archaeology and history,” The Tang Shipwreck: art and exchange in the 9th century, edited by Alan Chong and Stephen A. Murphy (Singapore: Asian Civilisations Museum, 2017), pp. 22–39.

[6] Flecker (2017), pp. 22–39.

[7] Alan Chong and Stephen A. Murphy, editors, The Tang Shipwreck: art and exchange in the 9th century (Singapore: Asian Civilisations Museum, 2017), p. 118.

[8] Regina Krahl, “Green, white, and blue-and white stonewares: A precious ceramic cargo,” The Tang Shipwreck: art and exchange in the 9th century, edited by Alan Chong and Stephen A. Murphy (Singapore: Asian Civilisations Museum, 2017), p. 103.

[9] Chong and Murphy (2017), pp. 118–19.

Additional resources

Edward A. Alpers, The Indian ocean in world history (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014).

Alan Chong and Stephen A. Murphy, editors, The Tang Shipwreck: art and exchange in the 9th century (Singapore: Asian Civilisations Museum, 2017).

Michael Flecker, “The origin of the Tang Shipwreck: A look at its archaeology and history,” The Tang Shipwreck: art and exchange in the 9th century, edited by Alan Chong and Stephen A. Murphy (Singapore: Asian Civilisations Museum, 2017), pp. 22–39.

Stephen A. Murphy, “Asia in the ninth century: the context of the Tang Shipwreck,” The Tang Shipwreck: art and exchange in the 9th century, edited by Alan Chong and Stephen A. Murphy (Singapore: Asian Civilisations Museum, 2017), pp. 12–21.

Natali Pearson, Belitung: The Afterlives of a Shipwreck (Honolulu: University of Hawaiʻi Press, 2023).

Regina Krahl, “Green, white, and blue-and white stonewares: A precious ceramic cargo,” The Tang Shipwreck: art and exchange in the 9th century, edited by Alan Chong and Stephen A. Murphy (Singapore: Asian Civilisations Museum, 2017), pp 80–105.