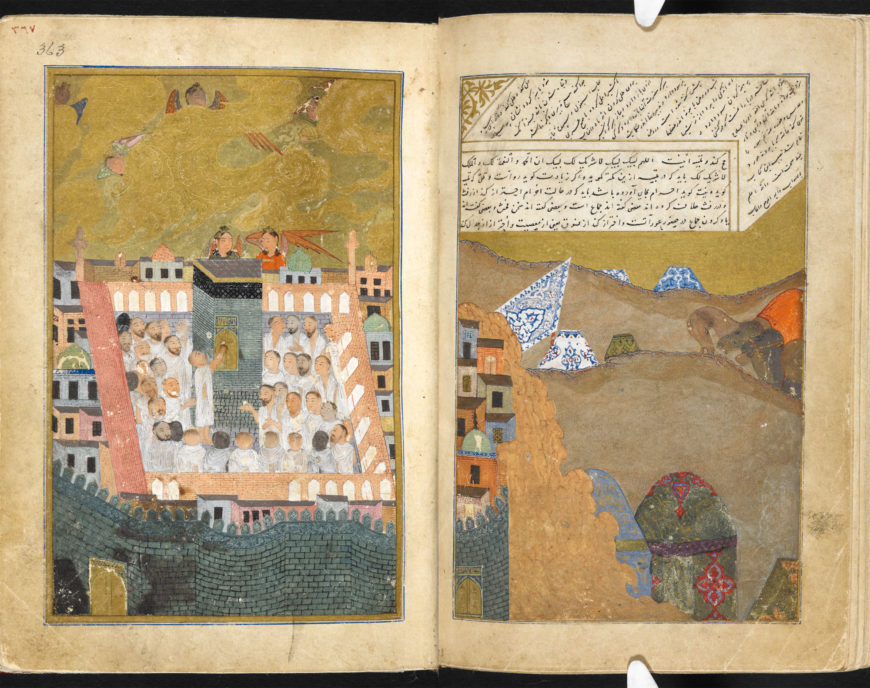

A Timurid painting of Mecca, depicting the pilgrims camping outside and making preparations. Miscellany of Iskandar Sultan, 1410–11, manuscript, 18.4 x 12.7 cm (The British Library, London)

What is hajj?

Hajj is undoubtedly the most well-known pilgrimage in Islam; it is one of the five pillars of Islam and is considered a duty for all Muslims who are in good health and can afford the journey to Mecca. It takes place during the month called Dhu al-Hijjah. Hajj has many rituals including tawaf (the circumambulation of the Ka‘bah) and sa’i (the running between the hills of Safa and Marwah). Umrah is similar to hajj but can take place at any time of the year. Pilgrims also enter the holy sanctuary of the Grand Mosque of Mecca through a different gate. The pilgrimage to the Ka‘bah is specified in numerous Qur’anic verses, including 5.97 which reads:

God made the Kabah the Sacred House

maintaining it for humanity

and the Sacred Month and the sacrificial gift

and the garlanded.

That is so that you will know that God knows

Whatever is in the heavens

And whatever is in the earth. Bakhtiar’s translation

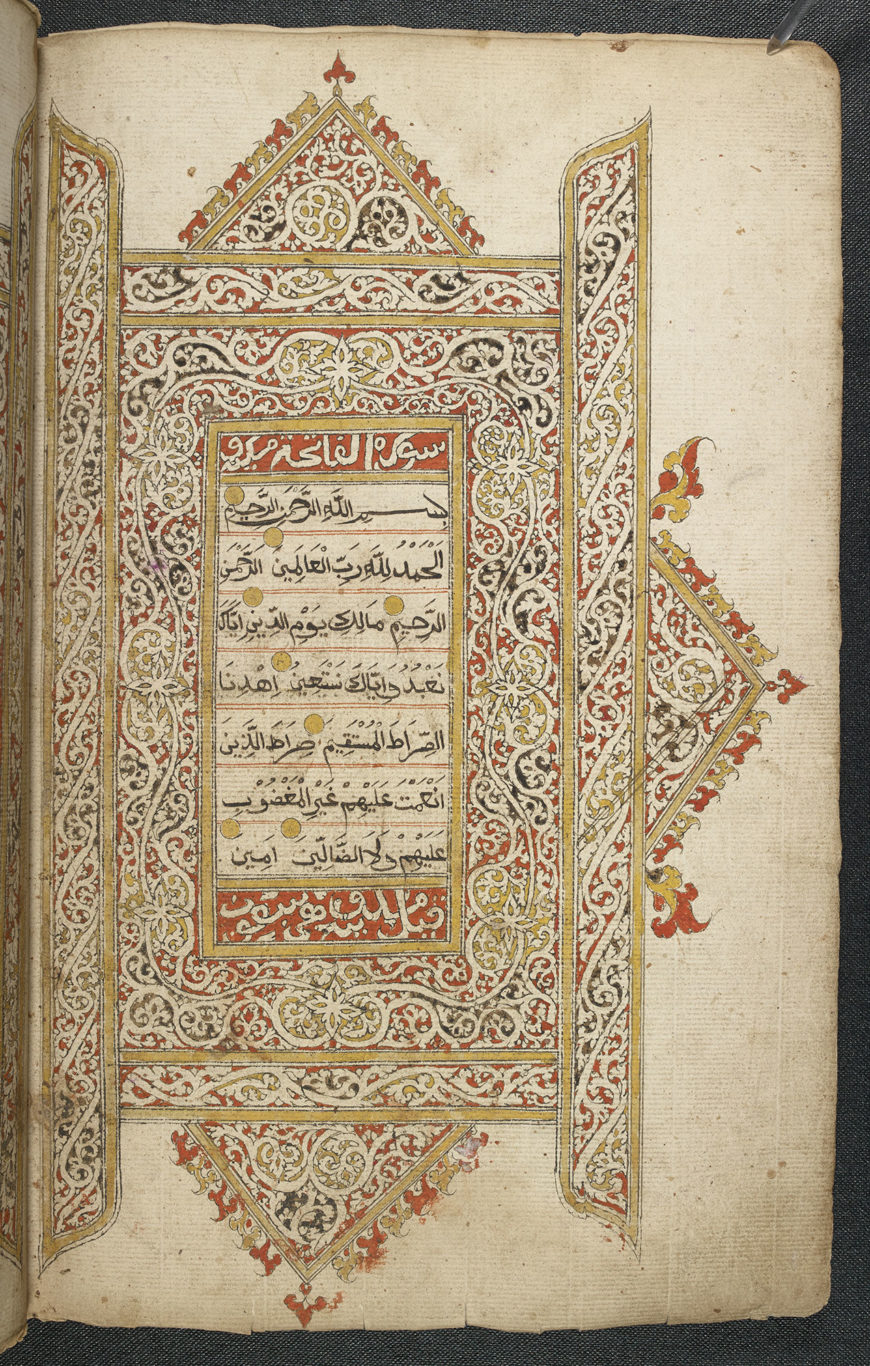

Illuminated opening page and folio showing Q 5:97 of a Qur’an manuscript from Aceh, early 19th century. Qur’an, early 19th century, manuscript, 33 x 20.5 cm (The British Library, London)

Hadiths are accounts of the Prophet’s life that determine much of Islamic practice. Some of these texts provide specifics on how to conduct the rituals associated with hajj. For example, one hadith reports that ‘The Prophet offered four rak’a of the zuhr prayer in Medina and two rak’a of ‘asr prayer at Dhu al-Hulaifa’. This hadith and others tell Muslims how to execute the particular rituals of hajj, which include specific prayers and supplications, as well as the order in which the traditions associated with hajj should be performed.

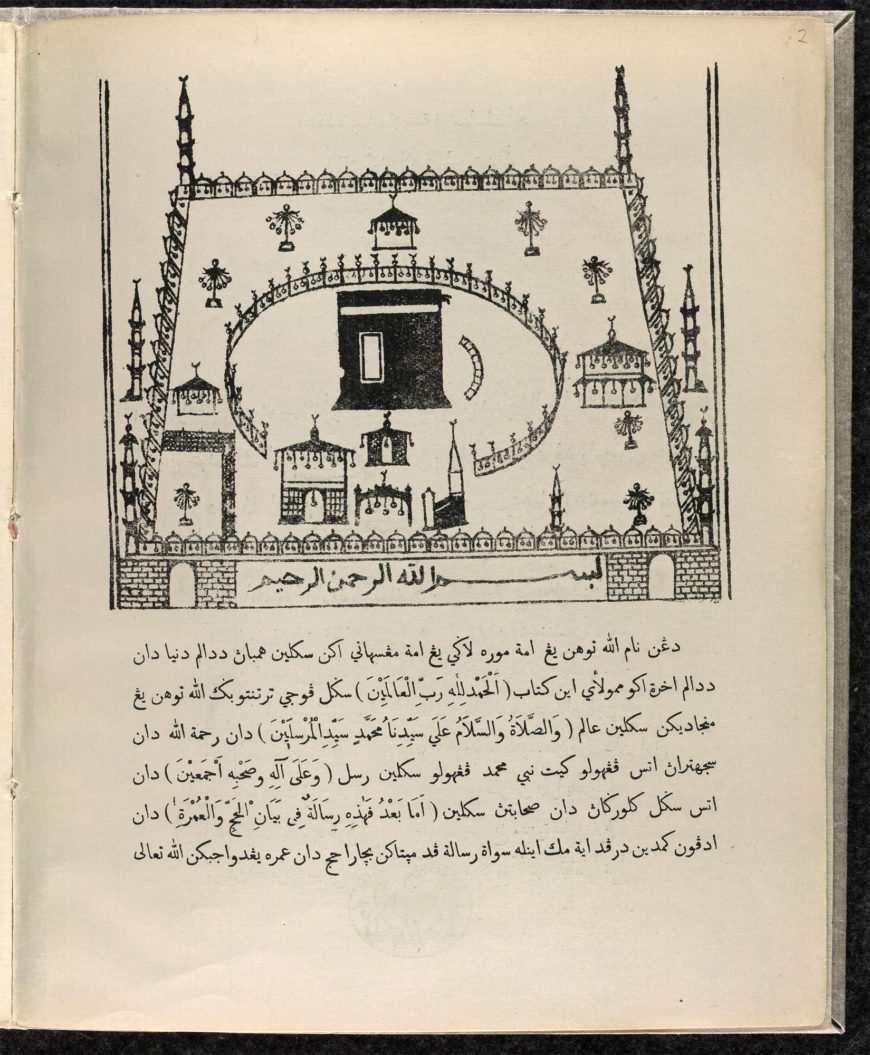

Pilgrimage guides also serve as an important aid for Muslims by giving instructions on what prayers and other supplications to perform at particular sites. For centuries these existed in a written form, while today Muslims also have the option of electronic forms of pilgrimage guides or smartphone apps, for both hajj and umrah, as well as for other pilgrimages known generally as ziyarat.

Illustration of the Ka‘bah in Mecca from a travel guide for pilgrims in Malay, Risalah majmu‘ah fi manasik al-Hajj by Muhammad Azahari bin Abdullah, published in Singapore in 1900 (The British Library, London)

The use of technology has altered hajj in other ways too. In previous centuries the only options for travel were by land or sea, and the journey could be both difficult and dangerous, as well as long. The advent of air travel has made it easier for Muslims to reach Mecca. Tour companies offering packages for umrah and hajj are also popular; their posters can be seen on billboards, in Islamic literature and online.

Why is Mecca so important to Muslims?

Mecca is important to Muslims for a number of reasons. The Prophet was from Mecca and returned there before his death. The Hira cave, on Jabal al-Nour, is reportedly where the Prophet received his first revelation. Islam is also an Abrahamic, monotheistic religion that is strongly rooted in the traditions associated with Judaism and Christianity. Muslims believe that Mecca is the place where Abraham and Ishmael built the Ka‘bah, an act referred to in Qur’an 3.96. According to Muslim tradition, the Prophet Muhammad returned the Ka‘bah (more formally called al ka‘bah al-musharrafah) to its former status as a monotheistic site, rescuing it from the polytheism that had taken it over in previous centuries.

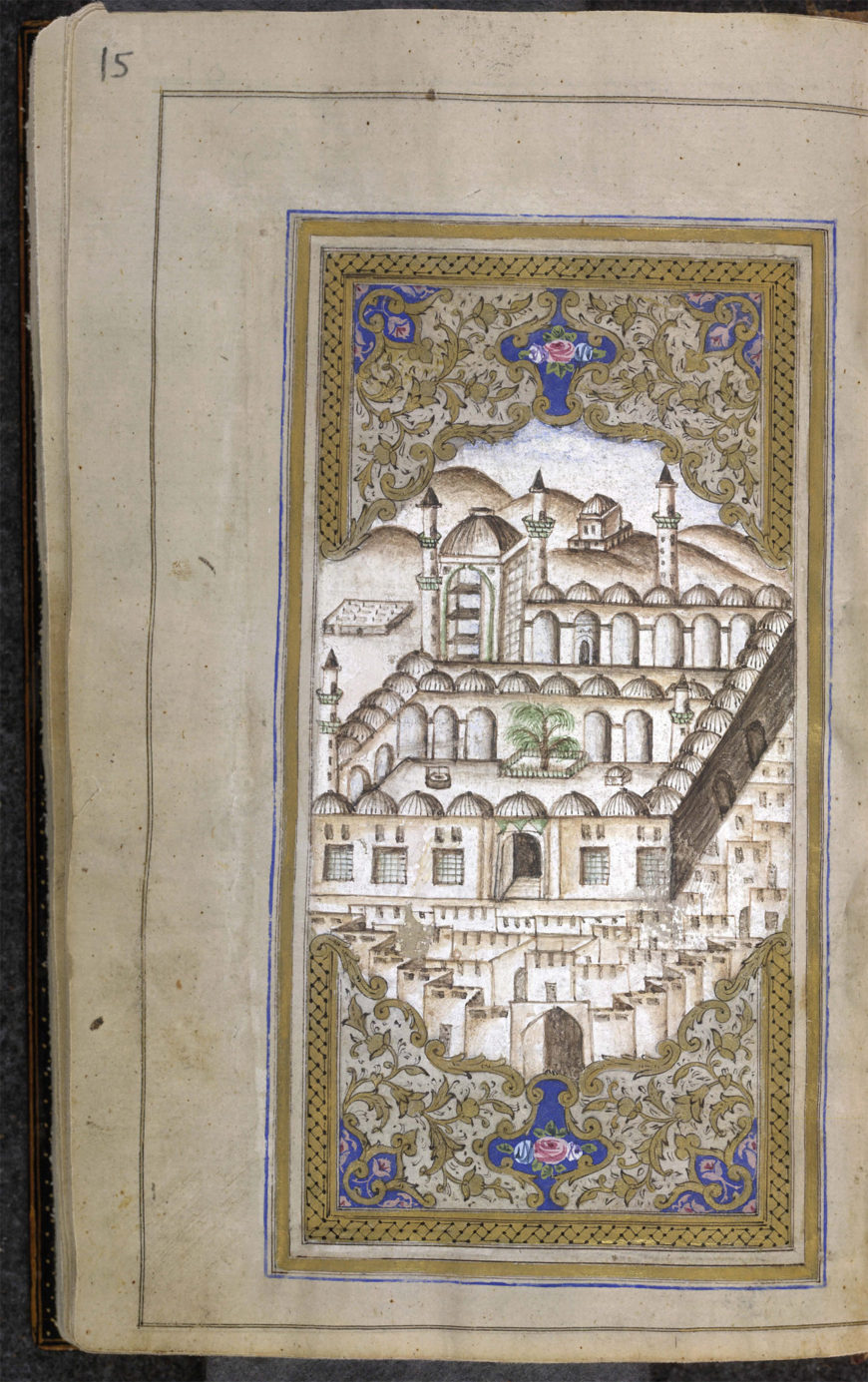

The holy city of Medina, as depicted in a copy of the Dala’il al-khayrat (Guide to Goodness), a devotional prayer-book, produced in India in the 19th century. Muhammad*ibn Sulayman al-Jazuli, Depiction of the holy cities of Mecca and Medina from Dala’il al-khayrat (Guide to Goodness), 19th century, India (The British Library, London)

Numerous cultural artefacts speak to the importance of Mecca for Muslims, as well as the religious duties associated with the city and its environs. Pictures of the Ka‘bah are found on posters, on carpets, in Muslim places of worship and in Muslim homes. Pictorial representations of the holy sanctuary are found in numerous Islamic cultures, executed in styles ranging from drawings and paintings to prayer rugs. In addition to paintings, drawings, and other artistic representations, hajj guides, maps, manuals and certificates inspired and recorded the experiences of pilgrims from the Hijaz to faraway lands such as Southeast Asia and Africa.

This 15th-century scroll from the commemorates the hajj by a woman called Maymunah. Seen here, reading downwards, are: the sanctuary of the Ka’bah at Mecca, the hill al-Marwah (depicted as a series of concentric circles), the shrine of the Prophet Muhammad at Medina, and the sole of the Prophet’s sandal, in which is written one of his sayings. Hajj pilgrimage certificate, 1433, manuscript (The British Library, London)

Are there other Islamic pilgrimages?

Outside of hajj and umrah, hundreds of other religious journeys are undertaken by Muslims around the world, ranging from local visits to family graveyards in Javanese villages to large-scale annual pilgrimages to cities such as Karbala and Mashhad. In part, the restrictions on hajj contribute to the popularity of these other pilgrimages. Islam is a global religion with over 1.7 billion followers, however only two million pilgrims can perform hajj each year due to safety concerns and the limited space of the sites. The expense of hajj and its distance from many Muslim communities are also barriers. Thus, Muslims around the world participate in other religious journeys known collectively as ziyarat. While not considered an obligation on the same level as hajj, these journeys are nonetheless popular. The other factor that may contribute to their popularity is that the range of places visited as part of these traditions is immense, and often reflect the cultural and religious variations in diverse Muslim communities. For instance, among popular ziyarat sites are the graves of Sufi saints, the large tomb complexes of Shi‘a imams, the mountains surrounding holy cities and the forests of Bosnia.

![This Ottoman-era book of model correspondence shows drawings of various tombs in Jerusalem, Mecca and Medina. The tombs depicted in the Hejaz were destroyed in 1926. Mustafa Efendi [scribe], İnşā’-i a‘là - انشأ اعلى, early 18th century, paper manuscript, 31 x 21 cm (The British Library, London)](https://smarthistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Early-18th-century-Ottoman-or_6261_198r-870x1301.jpeg)

This Ottoman-era book of model correspondence shows drawings of various tombs in Jerusalem, Mecca and Medina. The tombs depicted in the Hejaz were destroyed in 1926. Mustafa Efendi [scribe], İnşā’-i a‘là – انشأ اعلى, early 18th century, paper manuscript, 31 x 21 cm (The British Library, London)

Various debates surround the religious appropriateness of these ziyarat. These debates centre around who has the authority to determine proper Islamic tradition. Some Muslims are uncomfortable with pilgrimages outside of hajj; they are not universally accepted, yet they remain popular around the world, from Africa to Southeast Asia.

What pilgrimages are important to Shi‘a Muslims?

Muslims around the world have their own pilgrimage traditions that exist outside of hajj and umrah. In some cases, these are particular to a small community, such as the case of the local pilgrimages in Southeast Asia. In other cases, pilgrimage is a transnational affair, involving Muslims from every corner of the earth. The best case of this outside of hajj, umrah and popular Sufi sites such as Rumi’s tomb in Konya in Turkey, is found in the transnational pilgrimages of the Shi‘a.

For Shi‘a Muslims, the family of the Prophet and in particular the relatives of his daughter Fatima and her husband Ali (the Prophet’s cousin), are especially important. These relatives are recognised as the Twelve Imams and their family by the majority of Shi‘a, who consider the visitation of the Imams’ tombs, as well as those of their relatives, a duty.

![A guide book for pilgrims, including a 17th-century depiction of the Holy Shrine of Mecca. This 17th-century work describes of the holy shrines of Mecca and Medina and the rites of pilgrimage tombs. Shown here (left) are tombs of the Prophet’s family, and (right) the tomb of the Prophet’s wife Khadījah and others at Mecca. Muḥyī *Lārī [Muhyi Al-Din Lari], Futūḥ al-ḥaramayn (‘Revelations of the two sanctuaries’), 17th century, Iran, manuscript, 22.2 x 15.2 cm (The British Library, London)](https://smarthistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/17thc-manuscript-combo-870x604.jpg)

A guide book for pilgrims, including a 17th-century depiction of the Holy Shrine of Mecca. This 17th-century work describes of the holy shrines of Mecca and Medina and the rites of pilgrimage tombs. Shown here (left) are tombs of the Prophet’s family, and (right) the tomb of the Prophet’s wife Khadījah and others at Mecca. Muḥyī *Lārī [Muhyi Al-Din Lari], Futūḥ al-ḥaramayn (‘Revelations of the two sanctuaries’), 17th century, Iran, manuscript, 22.2 x 15.2 cm (The British Library, London)

The Muharram festival is in commemoration of Imams Husain. This festival starts on the first day of Muharram, the first month of the Islamic calendar, and lasts for ten days. Painting of a Muharram procession, gouache on mica, Benares or Patna style, 1830–40 (The British Library, London)

Sainthood in Islam

The question of sainthood in Islam is an interesting one. Islam does not have a canonisation process like, for instance, the Catholic Church. In academic literature, the word saint is often used to describe the awliya’ (wali, sing.), or the “friends of God.” These are individuals believed to be close to Allah. Sufi individuals such as Rumi, whose tomb in Konya sees millions of visitors a year, and Rabiah, who is buried in Basra, Iraq, are considered by many to be awliya’ . In other contexts, those close to Allah are culturally specific, such as the wali songo—the nine founding saints of Islam in Indonesia. There, numerous tombs of the wali songo populate the coastlines and interior of Java.

The oldest mosques on islands such as Lombok are visited by locals, Indonesians from other islands in the archipelago and by Muslims from as far away as Cairo. The Imams of the Twelver Shi‘a Imamate resemble more closely the early martyrs of the Christian Church, with the exception of the last Imam, who is believed to be in a state of occultation.

Sacred space in Islam

Sacred space is an important topic in understanding Islamic pilgrimage. The direction of prayer is the Ka‘bah, bringing the focus of Muslim prayer towards Mecca throughout the day. The qiblah (direction of prayer) is often marked by a sticker or other symbol in hotel rooms, so that Muslims can orient themselves for their daily prayers. Shi‘a, who like other Muslims face Mecca to pray, use a prayer stone (turbah) made from clay from a holy Shi‘a city, or place their forehead on the earth, illustrating the importance of the earth as a sacred tableau.

For Muslims, the world is Allah’s creation, hence the expression, “The world is your prayer mat.” This saying is likely inspired by a hadith of the Prophet’s in which he states, “The entire earth is a place of prayer except for graveyards and bathrooms.” Whatever the authenticity of the tradition, the Islamic view of space does not observe the religious and secular division that is more common in the West. Islamic practices such as removing one’s shoes before entering a mosque, shrine or home suggest that any place where prayer takes place is sacred. Some places, however, are more sacred due to their history, who is buried at the site or how many pilgrims visit the place. Scholars have named the sense of camaraderie generated by these pilgrimages communitas.

The importance of awliya’ and other important Muslim individuals shapes the sacred spaces associated with pilgrimage in Islam. In the case of the Prophet Muhammad’s grave in Medina, the presence of his body, the graveyard where he is buried (al-masjid al-nabawi) and the history of the early Muslim community (ummah), have shaped the history of the city. The Jannat al-Baqi, the graveyard adjoining the Prophet’s mosque, is the site of many of the graves of his relatives and companions. The renovations and expansions of his modest and small mosque, the first in Islam, which also served as his home during his lifetime, attest to the popularity of pilgrimage for Muslims, whether in Mecca, Medina or elsewhere in the world.

Written by Sophia Arjana

Sophia Arjana is Assistant Professor of Religious Studies at Western Kentucky University. She is the author of three books, Muslims in the Western Imagination (2015), Pilgrimage in Islam: Traditional and Modern Practices (2017), and Veiled Superheroes: Islam, Feminism, and Popular Culture (2017). Her forthcoming book is Buying Buddha, Selling Rumi: Orientalism and the Mystical Marketplace (2019).

The text in this article is available under the Creative Commons License.

Originally published by The British Library.