al-ʿAziz ewer, rock crystal, Cairo, 1001–10, with 16th-century gold and enamel mounts (Treasury of San Marco)

Handle and ibex thumb rest, al-ʿAziz ewer, rock crystal, Cairo, 1001–10, with 16th-century gold and enamel mounts (Treasury of San Marco)

Today, we often expect translucent forms to be made of glass or plastic, but rock crystal—a transparent variety of the mineral quartz—has long been valued as a rare medium, which could be shaped by craftsmen into precious objects. Gazing through the translucent walls of a rock crystal vessel, one is astonished by the dynamic changes in light and color as light passes across its surfaces.

This rock crystal ewer, found today in the Treasury of the Church of San Marco in Venice, is a unique testament to the height of rock crystal production at the court of the Fatimid caliphs in 11th-century Cairo.

Roughly pear-shaped, the ewer has a straight handle delicately carved with rows of drilled holes. The handle, today supported by a 16th-century gold and enamel mount, is topped with a carved rock crystal ibex, which provides a thumb rest for its user.

Lion with carved dots, al-ʿAziz ewer, rock crystal, Cairo, 1001–10 (Treasury of San Marco)

Two large sitting lions confronting a central plant formed of palmette motifs dominate the body of the vessel. The lions look upward, their mouths open. Their faces are detailed with long curved eyebrows, large round eyes, and small ears set off from their bodies by a narrow collar-like mane executed with deep grooves. Small dots cover the surface of their bodies, giving an impression of fur, while a half palmette appears on their hind legs.

Inscription “blessing from Allah for the imam al-ʿAziz Biʾllah” on al-ʿAziz ewer, rock crystal, Cairo, 1001–10 (Treasury of San Marco)

The short cylindrical neck of the ewer is encircled by bands, one of which includes the inscription, “blessing from Allah for the imam al-ʿAziz Biʾllah,” referring to the patron of the ewer, Fatimid caliph al-ʿAziz Biʾllah, who ruled in Cairo from 1001–10. Based on this inscription, the San Marco ewer is one of only three rock crystal objects that can be securely dated, and thus offers a rare window into patronage and production of luxury objects in 11th-century Egypt. [1]

From left: Mufloni ewer, rock crystal, Iraq, late 9th or early 10th century, with later mounts (Treasury of San Marco); ewer, rock crystal, Iraq, late 9th or early 10th century (Victoria & Albert Museum); al-ʿAziz ewer, rock crystal, Cairo, 1001–10, with 16th-century gold and enamel mounts (Treasury of San Marco); ewer, rock crystal, Cairo, 1000–8 (Palazzo Pitti); ewer, rock crystal, Cairo, 10th–11th century (Fermo Cathedral); St. Denis ewer, rock crystal, Cairo, ca. 1000, with later mounts (Louvre); Keir collection ewer, rock crystal, Cairo, first half of 11th century with 19th-century mounts (Dallas Museum of Art)

The San Marco ewer is one of seven extant rock crystal pear-shaped vessels thought to have been produced as luxury objects for the Abbasid and Fatimid courts. All masterpieces of rock crystal carving, they are described today by scholars as the “Magnificent Seven.” [2] They stored and dispensed liquids for use during ceremonial banquets. We can imagine the sparkle emanating from the ewers’ carved and polished surfaces as the liquid, visible within, poured forth during a festive occasion.

Left and center: rock crystal cylinder seal (with interior paint) and the impression it creates, Ur, Iraq, ca. 2200 B.C.E, rock crystal with interior paint (British Museum); right: Roman skyphos, first century C.E., Alexandria (?), rock crystal (Treasury of San Marco)

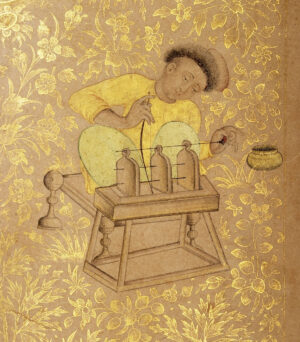

Engraving a gemstone with a bow lathe, detail from the border of a manuscript page from a Jahangir album, India, c. 1610–11 (Náprstek Museum)

Rock crystal carving and techniques

Rock crystals have been mined since antiquity, and were widely sought across ancient Mesopotamia, Persia, and Egypt, with early production peaking in the first two centuries of the Roman Empire. In ancient Mesopotamia, rock crystal was among the first materials used in the production of cylinder seals. In the example above, the addition of paint to a cavity within the seal gives the impression of three-dimensionality to the carved scene. Roman rock crystal vessels were largely left undecorated. Their highly polished surfaces were meant to highlight the purity of the crystal material. In contrast, the San Marco ewer and other rock crystal objects produced in 9th–10th century Iraq and 10th–11th century Egypt championed the craftsmen’s mastery of the crystal and their ability to carve intricate high-relief designs onto the surface without damaging the material. Alongside objects of the highest craftsmanship commissioned by members of the court, a range of rock crystal objects, including tablewares, perfume bottles, lamps, chess pieces, rings, amulets, and weapons, were also sold in urban markets.

The crystals underwent several stages of carving and decoration. Abrasive powders made from harder stones than quartz were combined with water or oil as a lubricant. This mixture was then brought into contact with the surface of the crystal with various metal tools, including bow saws, grinding wheels, bow lathes, and tubular drills, in order to carve and hollow out the final shape of the vessel. The San Marco ewer, including its integral handle, was carved from a single piece of rock crystal. The walls of the body of the ewer are remarkably thin, less than 2mm in some areas. This was extraordinarily difficult to achieve without shattering the crystal and served no practical purpose. Rather, it displayed the bravura of the craftsman, highlighting their own skill in carving such a masterpiece and adds to its rarity and aesthetic appeal.

Once a final form was achieved, the surface of the vessel was carved leaving areas of relief that stand above the surface of the vessel. Details, including palmettes, leaf-scrolls, circular dots, and line-and-dot motifs, were carved into the surface. These details highlight the rock crystal’s superior ability to reflect light, with the carved details causing light to travel in different directions when it hits its surface. The result, in the case of this masterpiece of rock crystal carving, are color and light effects that no photograph can capture.

Rock crystal trade: from Madagascar and the Swahili Coast to Basra and Cairo

Although carved and sold in Iraq and Egypt, medieval trade in raw rock crystal connected West Asia and North Africa with East Africa. The San Marco ewer required an exceptionally large and clear crystal of pure quartz. It is likely that it was mined in Madagascar and then traded in the Comoros Islands just off of what is today the Swahili Coast. Dembeni, one of the largest trading ports, served as a major distribution center for Madagascar rock crystal from the 9th–12th centuries. Arab and Persian traders brought ceramics, fabrics, beads, and glass to exchange for high quality crystals, as well as for ivory, gold, and enslaved people. From Dembeni, rock crystal traveled north to the ports of Aden in Yemen, and ultimately to Basra and Cairo, the primary Abbasid and Fatimid production centers of crystal objects in the 9th–12th centuries. The cost of acquiring such large, flawless crystals, imported across thousands of miles was surely immense, and explains the association of rock crystal production with royal courts.

al-ʿAziz ewer, rock crystal, Cairo, 1001–10, with 16th-century gold and enamel mounts (Treasury of San Marco)

Transparency and clarity

According to al-Biruni, a medieval Iranian astronomer, mathematician, and philosopher, “[rock crystal] is regarded noble because of its transparency and clarity, and also because it is like the essential elements of life, i.e., air and water.” [3] For medieval patrons, rock crystal’s transparency was its most important quality. The very best crystals, like the San Marco ewer, were reserved for complex objects produced for the court of the caliph. Smaller crystals with imperfections—perforations or cloudy areas—were likely carved in commercial workshops and sold to the wealthy urban elite.

Alongside its transparency, rock crystals were appreciated for the curative, magical, and spiritual qualities ascribed to the material. Ancient and medieval sources generally agree that rock crystals originated as water and later solidified in the course of a long natural process. This perceived duality—as both liquid and solid—is an expression of its own appearance, shining and bright, and yet also transparent. Its translucent and reflective qualities and its seemingly magical origins are compared with transcendence and spiritual light in the Hebrew Bible, New Testament, and Qur’an, while in Islamic literature and poetry they evoke paradisiacal and palatial connections. [4]

al-ʿAziz ewer in the San Marco Treasury, rock crystal, Cairo, 1001–10, with 16th-century gold and enamel mounts (Treasury of San Marco)

Transformation and reuse in western Europe

Today, a limited number of rock crystal objects remain in the lands of Islam; the majority, including the most outstanding examples, traveled from the 10th–13th century through trade, war, and diplomatic exchange to western Europe, where they were preserved in church treasuries and palace collections.

We don’t know the precise journey that each object took to western Europe. However, many of the most valuable rock crystal objects were dispersed from Cairo in 1068–69 in the midst of an economic and political crisis known as al-shidda al-ʿuzma, or “the great calamity.” The Nile failed to flood leading to widespread famine. Following several years of drought during which the Fatimid armies received no payment, the palace’s treasury, where the caliph stored his most prized possessions, was systematically looted. According to a contemporary account, among the objects brought out from the Treasury and sold on the open market were 36,000 pieces of rock crystal. [5] Another account reported that a witness had seen in the market of Tripoli a rock crystal ewer from the Fatimid Treasury, “extreme in purity and beauty of craftsmanship,” with the name al-ʿAziz Biʾllah inscribed on it. [6] It is tempting to think that the ewer spotted in Tripoli is the very same one that can be seen today in San Marco.

Left: Ambo of Henry II, 1002–14, in the Palatine Chapel, Aachen; right: rock crystal saucer-shaped dish surrounded by chess pieces, ambo of Henry II, 1002–14, in the Palatine Chapel, Aachen (photos: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

While we may never know the San Marco ewer’s path to Venice, once in Europe, the ewer and other rock crystal objects were similarly treasured for their clarity, transparency, and ability to reflect light. In their new environment, however, the material often assumed Christian theological and symbolic connotations, associating the purity of the crystal with the Virgin and Christ. Likewise, the vessels were put to radically new uses—rather than luxurious tableware in the Fatimid palace, the San Marco ewer was likely used in the service of the church. In the early 11th century, for example, a rock crystal cup and dish were incorporated into Ottonian king Henry II’s ambo. Divorced from their original functions, they were presented alongside other spolia, including agate bowls and chalcedony chess pieces.

Many of the rock crystal objects that arrived in Europe were reused as Christian religious vessels, and in particular reliquaries. Rock crystal’s durability and transparency made it an ideal medium to both preserve and make visible the precious relics placed within. A small rock crystal vessel, for example, likely originally a perfume flask, was transformed into a reliquary in the 14th century with the addition of a gilded silver cap and foot. A Latin inscription on the cap reads, “the hair of the blessed Mary,” indicating the object’s reuse as a container for the precious relics of the Virgin.

From Madagascar to Cairo to Venice, the San Marco ewer’s rock crystal was revered for its flawless transparency, the symbolic meanings associated with its material, its rarity, and its superior craftsmanship.