The Museum of Islamic Art in Cairo was damaged by a bomb in 2014. It reopened in January of 2017. (Photo: Gérard Ducher, CC BY-SA 2.5)

For centuries, Egyptian archeological sites have been looted to feed the black market trade in antiquities. With so many priceless artifacts wrenched from their home in Egypt, it feels as though we are fighting an impossible battle.

This situation is particularly acute following the Egyptian revolution of 2011 and the ensuing political instability. Having experienced two revolutions in as many years, the majority of Egypt’s key archeological sites have fallen victim to looting. According to the International Coalition to Protect Egyptian Antiquities, around $3 billion worth of Egyptian antiquities have been looted since the troubles began in January 2011. Subsequently the antiquities market has been inundated with artifacts of Egyptian origin, as reported in the Washington Post.

It is not only archaeological sites at risk; extensive damage has been inflicted on the country’s leading museums. Over a hundred valuable artifacts were destroyed at the Museum of Islamic Art in Cairo in early 2014 when a car bomb detonated outside the building. Likewise nearly all of the collections, numbering more than a thousand artifacts, were looted from the Malawi National Museum in Upper Egypt in 2013 amidst the unrest.

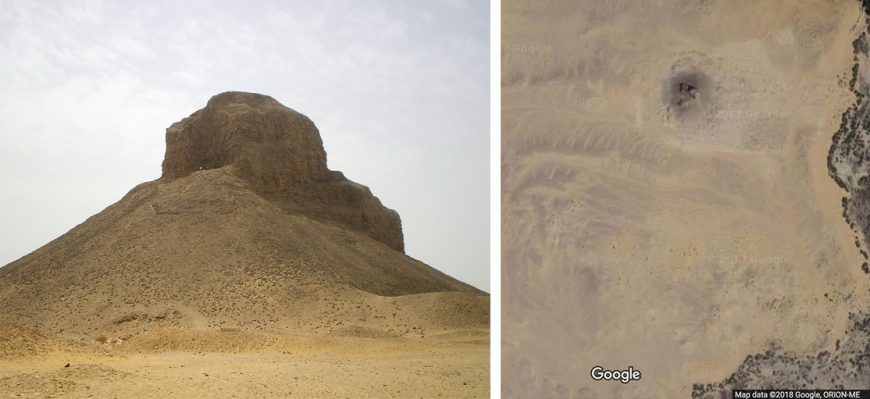

Left: Looting has been documented near the pyramid of Amenemhat III at Dahshur, Middle Kingdom, 1860–1814 B.C.E. (12th Dynasty), (photo: Tekisch, CC BY-SA 3.0); Right: Satellite view of the pyramid and looted areas to the south (©Google, 2018)

What is at stake for Egypt?

There are seven cultural and natural properties in Egypt inscribed on the World Heritage list, in addition to 32 sites on the tentative list. One of these properties includes the pyramid fields from Giza to Dahshur, a region known to be brutally pockmarked with holes dug by looters in search of saleable artifacts. BBC Cairo reporter Aleem Maqbool reports vertical shafts and tunnels, presumably dug in the hopes of finding archaeological material scattered across the landscape.

Armed robbers have also attacked storehouses holding antiquities from ongoing excavations, most of which were unregistered, meaning we have no idea just how many objects were lost. This loss of knowledge is incalculable.

“We are losing a lot of the monastic graffiti (Coptic, Syriac, Ethiopian, and Demotic) and several other archaeological features. Egyptian history is being destroyed….” Archeologist Monica Hanna told SAFE.

Before the Arab Spring revolution in 2011, tourism accounted for more than ten percent of Egypt’s gross domestic product. Since then, the tourist industry has struggled to find its footing amidst economic and political uncertainty. According to official statistics, foreign tourists have been returning to Egypt slowly but surely, with over a million visiting in April 2013. Although these numbers are increasing, they nevertheless remain well below pre-revolution levels, putting a serious strain on an industry that used to support a substantial portion of the population. Moreover, in a country where unemployment is rife, the budget deficit continues to grow, and the currency has lost much of its value, looting can appear to be a “get rich quick” occupation. It is of the utmost importance to protect Egypt’s cultural heritage in this turbulent time.

Egypt’s cultural heritage endangered

Egypt is home to one of world’s the oldest civilizations whose millennia of recorded history have had a profound influence on the cultures of Europe, the Middle East, and Africa. Although Egyptian archaeological sites have for centuries been looted to feed the black market trade of antiquities, recent upheavals in the region have led to the exposure of its material to the ravages of rampant looting. While the market demand remains strong, Egyptian antiquities are among the most valuable—and vulnerable—in the world.

To meet this demand, looters are even breaking the taboo of going into a tomb to store their loot in a location others won’t have the audacity to enter. Betsy Hiel of the Pittsburgh Tribune-Review reported about a family of looters who stored their artifacts in an already plundered tomb because “[n]o one would dare to take it.” One member of the family even bragged that “we don’t need fakes anymore” because there are so many vulnerable originals up for grabs. Armed criminal gangs have also been known to ravage the endangered sites in search of both antiquities and valuable land.

The pyramids of Abusir (Abu Sir Al-Maleq) (photo: Francesco Gasparetti, CC BY 2.0)

Archeologist Monica Hanna believes that many of the looters are looking for quick gold due to a mistaken belief that gold is readily available. At the site Abu Sir Al-Maleq, a burial ground about 70 miles from Cairo, there are piles of bones and mummy wrappings that have been hastily discarded as looters pick through on the hunt for quick cash. Although these looters might gain a small sum of money, what they are losing is far greater: the ability to understand past cultures. Hanna says the case of Abu Sir Al-Maleq is even more tragic because it has not been fully excavated, meaning that only salvage archeology can be conducted at this point.

Other threats to archaeological sites include encroachment on the land by residents trying to expand their homes or property, or repurposing of the land for use as landfills or car parks. This damages unexcavated sites, forcing archeologists to expedite their work and potentially miss crucial discoveries. After a new structure has been built on top of an unexcavated site, ancient artifacts might not be found for decades or even centuries, if ever.

Objects in museums are not immune to destruction. In August, 2013 thieves broke into the Mallawi Museum in the Upper Egypt city of Minya, destroying 48 artifacts and stealing 1,041 objects. Although nearly 600 artifacts were recovered, another museum became the target of destruction only months later. In January 2014 Cairo’s Museum of Islamic Art—home to one of the world’s most important collections of its kind—was hit by a bomb blast.

Market demand for Egyptian antiquities

Egyptian archeologist Heidi Saleh has stated that as long as the market continues to drive demand for Egyptian antiquities, the looting will continue. As she says in a newspaper article from June 2013, “antiquities have become a low priority for the average Egyptian” and that unless foreign collectors stop purchasing unprovenanced artifacts, the looting will continue—perhaps indefinitely.

After the revolution in 2011, international museums were on the on the lookout for artifacts that were potentially illicitly obtained. The Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology in London released a statement saying that, “All of us who are friends of Egypt can help the efforts to stop looting of archaeological sites, stores and museums, by focusing on the international antiquities trade.”

In December 2010, a mere 13 Egyptian artifacts sold for a reported total of $9,789,500. With a market demand capable of driving prices to such dizzying heights, it seems unlikely that auction houses or dealers will stop trading in Egyptian antiquities any time soon.

The sale of illicit artifacts is also taking place online. In February 2014, SAFE commented on the progress of curtailing sales of Egyptian antiquities on the world’s largest online auction site, eBay. According to a report in the Cairo Times, eBay has agreed with the U.S. Egyptian Embassy to stop the sale of Egyptian antiquities.

There is an ongoing debate surrounding the St. Louis Art Museum’s Ka-nefer-nefer mummy mask, purchased in the late 1990s. Other prominent cases include the conviction of antiquities dealer Frederick Schultz and the looting of the Mallawi Museum south of Cairo. Some of the objects looted from Mallawi have been recovered, but many more are still lost, vulnerable to the illicit trade.

What is Egypt doing to protect its cultural heritage?

Relevant laws and treaties

Protecting Egypt’s cultural heritage is enshrined in the country’s constitution, with Articles 12 and 49 committed to protecting Egyptian heritage through education and artistic freedom. Yet while the excavation and exploitation of ancient Egyptian sites dates back hundreds of years, the UNESCO Database of Cultural Heritage Laws indicates that it wasn’t until 1912 that the “Regiement pour l’Exportation des Antiquites” established a structured system for the exportation of antiquities.

The 1983 Law on the Protection of Antiquities clearly states that, “all antiquities are considered public property.” Any antiquity originating from Egypt belongs to the government and may not be obtained, purchased, or sold by a private individual. The 1983 law also gives merchants a grace period of a year to liquidate any antiquities that they might have in their possession—a time limit that has clearly been violated for more than two decades.

International treaties include the 1954 Hague Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict (with Regulations for the Execution of the Convention) and the 1970 UNESCO Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property.

Other Efforts

In May 2013, ordinary citizens joined together to protect the site of Dahshur around the clock in response to the reports of looting around the pyramids.

After looters broke into the Cairo Museum in 2011, hundreds of people formed a human chain around its perimeter to prevent the looters from escaping. This kind of story is inspiring, and it demonstrates the public’s desire to protect Egypt’s cultural heritage, although it is not feasible for such actions to be taken at every site in Egypt.

In June 2013, the National Committee of Egyptian Archaeological Sites was established to oversee the protection of Egypt’s World Heritage sites. The committee includes representatives from the Ministry of State for Antiquities as well as regional representatives. However, this committee provides little respite for uninscribed sites from the epidemic of looting and destruction.

Fekri Hassan, the Cultural Heritage Director at Egypt’s French University, is working with the United Nations to train “heritage guardians” as guides for Dahshur, a site that has taken the brunt of much of the looting.

According to this report in the Cairo Times, the world’s largest online auction site, eBay, has agreed with the U.S. Egyptian Embassy to stop the sale of Egyptian antiquities. This could mean a significant deterrent to the illicit trade, and in turn, a disincentive to loot.

Archaeologists such as Monica Hanna have spoken out in defense of Egypt’s cultural heritage and made important issues part of a public discussion. There have also been efforts via social media, such as the Facebook page “Stop the Heritage Drain” and “Egypt’s Heritage Task Force,” which post pictures and live updates of sites damaged by looting.

Other efforts to protect Egypt’s heritage

The International Council of Museums (ICOM) published the Emergency Red List of Egyptian Cultural Objects at Risk, listing categories or types of cultural items that are most likely to be illegally bought and sold. This adds to other Red Lists of objects from twelve other countries produced by ICOM.

In March of 2014, the Egyptian Antiquities Minister and the U.S.-based International Coalition to Protect Egyptian Antiquities (ICPEA) signed an agreement to protect Egyptian cultural heritage sites and antiquities from looting and cultural racketeers. According to ICPEA’s website, they have agreed upon a series of short-, medium-, and long-term programs to strike at the core of the cultural racketeering.

There are dozens of Facebook groups that aim to support Egypt’s cultural heritage, where members share news of the latest looting incident and aim to support those in Egypt by calling for greater protection of sites. Some of these include Protect Egyptian Cultural Heritage, The Society for the Study of Egyptian Antiquities, Egypt’s Heritage, and Save El Hibeh Egypt. Monica Hanna’s active Facebook page Egypt’s Heritage Task Force has thousands of followers from around the world.

Continuing media coverage of looting and destruction of heritage sites in Egypt shows a desire to learn about and prevent such incidents from happening. Nevine El-Aref’s roundup of the damage that happened during 2013 demonstrates that protecting Egypt’s cultural heritage is as relevant an issue as ever. Increased public awareness in and out of Egypt, facilitated by social media tools, will no doubt play a critical role.

On April 16, 2014 the U.S. State Department announced that Egypt requested that the U.S. impose import restrictions on Egyptian antiquities, made under Article 9 of the 1970 UNESCO Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property, to which both Egypt and the U.S. are state parties. The Cultural Property Advisory Committee (CPAC) received public comment on this request in an open session on June 2-4, 2014 in Washington.

What our partners at SAFE are doing to protect Egyptian cultural heritage

One month after the Arab Spring revolt of 2011, SAFE created the Say Yes to Egypt’s Heritage, Our Heritage campaign to show solidarity for the people of Egypt and raise awareness about the alarming threats to Egypt’s cultural heritage. In addition to content on the website highlighting the issues, “Say YES to Egypt’s Heritage” buttons were distributed around the globe. The campaign relaunched in 2014 to distribute buttons in Egypt, in honor of the Egyptian archaeologist Dr. Monica Hanna, the SAFE Beacon Award Winner. SAFE gathered some of these efforts outside of Egypt here.

You can read a SAFE discussion and analysis of recent sales in Egyptian antiquities here.