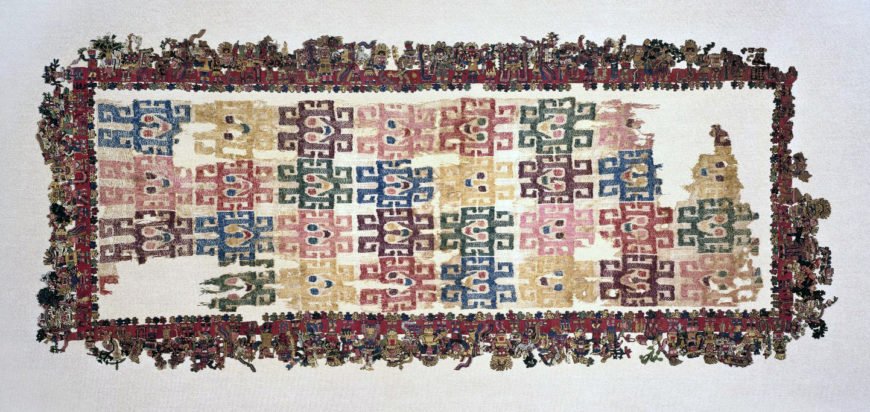

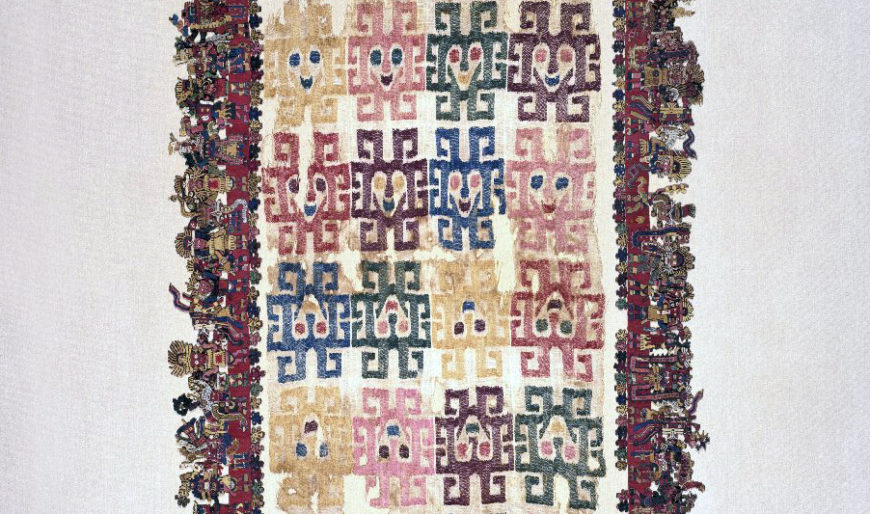

Nasca, Mantle (“The Paracas Textile”), 100–300 C.E., cotton, camelid fiber, 58–1/4 x 24–1/2 inches / 148 x 62.2 cm, found south coast, Paracas, Peru (Brooklyn Museum)

Mummy bundles

One of the most extraordinary masterpieces of the pre-Columbian Americas is a nearly 2,000-year-old cloth from the South Coast of Peru, which has been in the collection of the Brooklyn Museum of Art since 1938.

Despite the textile’s small size (it measures about two by five feet), it contains a vast amount of information about the people who lived in ancient Peru; and despite its great age and delicacy, its colors are brilliant, and tiny details amazingly intact. This is due to the arid environment of southern Peru along the Pacific shore, where it is so dry that organic material buried in the sand remains well preserved for hundreds or even thousands of years.

Paracas National Reserve, Peru (photo: Edubucher, CC BY 2.0)

In the ancient cemeteries on the Paracas Peninsula, the dead were wrapped in layers of cloth and clothing into “mummy bundles.” The largest and richest mummy bundles contained hundreds of brightly embroidered textiles, feathered costumes, and fine jewelry, interspersed with food offerings, such as beans. Early reports claimed that this cloth came from the Paracas peninsula, so it was called “THE Paracas textile,” to mark its excellence and uniqueness. Currently, scholars have revised this provenance, and now attribute the cloth to the related, but slightly later Nasca culture.

Thread by thread

Recently, the Brooklyn Museum has posted high quality, close-up views of this masterpiece online, allowing viewers to scrutinize the textile, thread by thread. Such a detailed inspection has not been possible since the piece was first made. With simple tools, the early cultures of the Andean region of South America produced textiles of astonishing virtuosity. Some extremely fine pieces, like this one, are too delicate to have served any utilitarian purpose, and so are considered ceremonial.

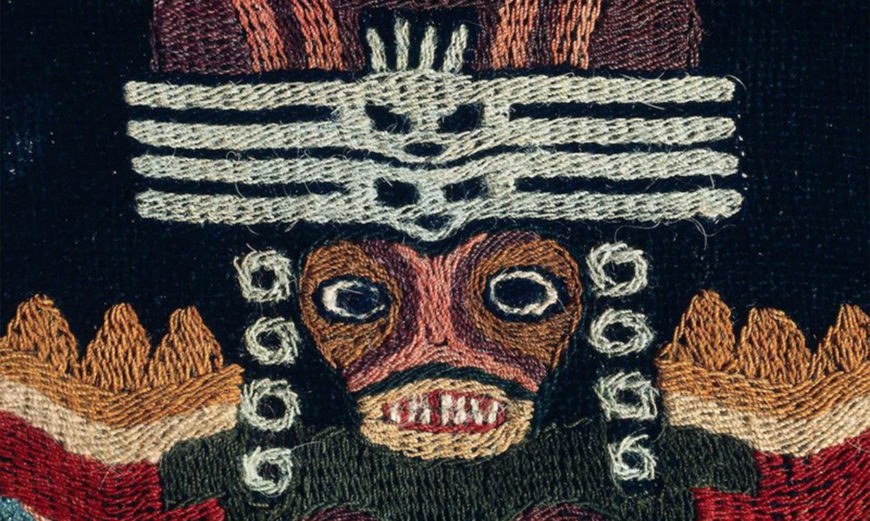

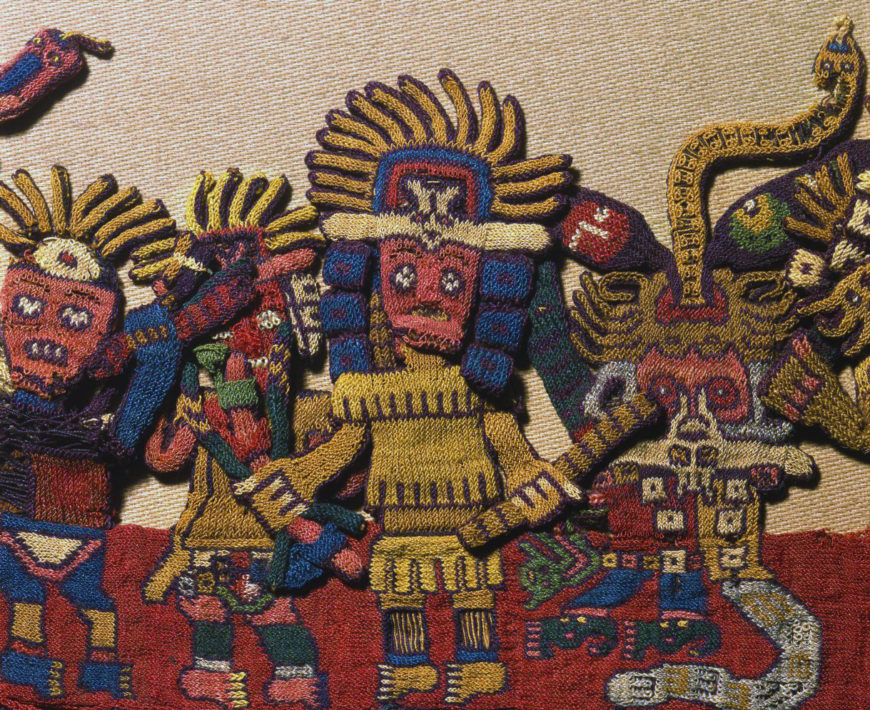

Detail of border figure 61, Nasca, Mantle (“The Paracas Textile”), 100–300 C.E., cotton, camelid fiber, 58–1/4 x 24–1/2″ / 148 x 62.2 cm, found south coast, Paracas, Peru (Brooklyn Museum)

Like some other very fine cloths, the Brooklyn textile is finished so carefully on both sides that it is almost impossible to distinguish which is the correct side. Although the central cloth and its framing dimensional border are created by different techniques, both display perfect reversibility—except for three border figures. These three—instead of being duplicated on the back (as if flipped in mirror image), like all the others—appear in back view on one side of the cloth, thereby designating a “front” and “back” to the textile.

Center detail, Nasca, Mantle (“The Paracas Textile”), 100–300 C.E., cotton, camelid fiber, 58–1/4 x 24–1/2 inches / 148 x 62.2 cm, found south coast, Paracas, Peru (Brooklyn Museum)

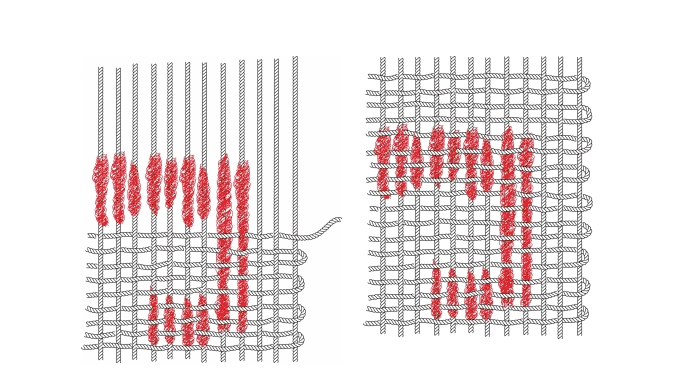

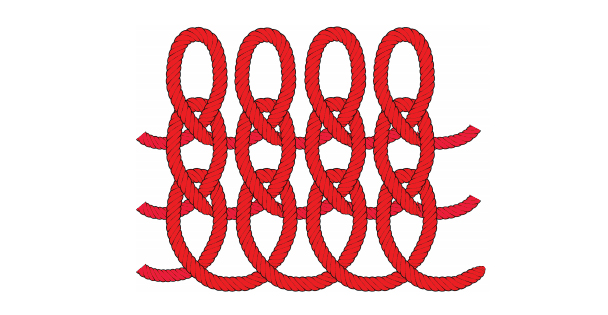

The central cloth’s design of 32 geometric faces is created by “warp-wrapping,” a technique in which colored fleece is wound around sections of cotton warp threads before weaving. Because the central cloth and the border have different color palettes, they may have been created at different times. The triple-layer border has colorful outer veneers of wool “crossed-looping” that envelop inner cotton cores of looping or weaving.

“Crossed-looping” resembles knitting (but is accomplished with a single needle); in areas where the threads are broken, it is possible to glimpse the underlying cotton substrates. While the cotton is off-white, the wool is dyed in jewel-bright tones.

Alpaca herd, Ausangate, Peru (photo: Marturius, CC BY-SA 3.0)

The combination of materials suggests extensive trading relationships: for while cotton was grown in coastal valleys, wool came from camelids (such as the llama, alpaca, and vicuña) that live at high altitudes in the Andes mountains.

The llama is laden with a bounty of vegetables. Since pre-Columbian people had no wheeled vehicles for transport, llama caravans carried goods between regions. Border figure 26, Nazca, Mantle (“The Paracas Textile”), 100–300 C.E., cotton, camelid fiber, 58–1/4 x 24–1/2 inches / 148 x 62.2 cm, found south coast, Paracas, Peru (Brooklyn Museum)

Monstrous hybrids

On the border, a parade of 90 figures is linked together on their lower bodies, which are worked two-dimensionally against a red background.

Detail of border figures (composite photo), Nasca, Mantle (“The Paracas Textile”), 100–300 C.E., cotton, camelid fiber, 58–1/4 x 24–1/2 inches / 148 x 62.2 cm, found south coast, Paracas, Peru (Brooklyn Museum)

Each figure’s upper body and head is constructed as a separate unit, and attached to the woven strip. The upper bodies are worked in bas-relief, with some parts projecting outwards from the plane of the fabric. Tiny components (like leaves and feathers) were worked as separate pieces and then attached, giving a wonderful three-dimensionality and liveliness to the figures, especially because they mingle and overlap.

Nasca, Mantle (“The Paracas Textile”), 100–300 C.E., cotton, camelid fiber, 58–1/4 x 24–1/2 inches / 148 x 62.2 cm, found south coast, Paracas, Peru (Brooklyn Museum)

The parade is arranged in four, single-file, L-shaped lines that proceed around each corner of the cloth. A wide variety of types appear, including human, animal, and monstrous hybrids. Some figures are unique, others are twins, triplets, or even sextuplets; a few are in related groups.

Most of the animals and plants that appear can be tied to species still found on the South Coast, and many human figures wear or carry items that directly relate to the archaeological record.

Nasca mouthmask, 300–700 C.E., gold with cinnabar, Peru (de Young Museum, San Francisco)

Their jewelry, for example, corresponds to specimens formed from thin sheets of gleaming gold. These include: “forehead ornaments” (shaped like a bird with outstretched wings); “hair spangles” (disk or star shapes that dangle from the wingtips of the forehead ornament); slender, feather-shaped headdress “plumes;” and “mouthmasks.” Mouthmasks hung from the nose septum, and had flaring extensions, like cat whiskers.

Detail with face ornament, border figure 63, Nasca, Mantle (“The Paracas Textile”), 100–300 C.E., cotton, camelid fiber, 58–1/4 x 24–1/2″ / 148 x 62.2 cm, found south coast, Paracas, Peru (Brooklyn Museum)

Garments

The border figures’ clothing also matches examples found archaeologically, and some bear minuscule designs that faithfully represent embroidered decorations found on life-sized garments. Some wear wrap-around dresses of a style worn by women in ancient times; others wear two-part outfits, associated with men (below). The largest and most beautifully decorated garments were mantles that draped over the shoulders, and fell to the knee. By examining stitches on actual mantles, archaeologists have determined that teams of artists worked on them, sitting side-by-side.

One of three figures with a front and back, painted or tattooed skin, wears a bristling mouthmask, and a headdress with flower-like plumes. He carries a striped staff topped with a winged creature, and wears a tunic and loincloth. Over his shoulder hangs a boldly-patterned mantle ending in a feline. Detail of border figure 16, Nasca, Mantle (“The Paracas Textile”), 100–300 C.E., cotton, camelid fiber, 58–1/4 x 24–1/2″ / 148 x 62.2 cm, found south coast, Paracas, Peru (Brooklyn Museum)

Other border details, rather than realistic, seem to be fantastic or mythological. The severed heads (sometimes called “trophy heads”) brandished by some figures, for example, sometimes sprout flourishing plants—as if to suggest themes of sacrifice and fertility. And snake-like streamers that flow from some figures do not correspond to any known object, and may indicate supernatural qualities.

Pampas cat and tree, border figure 3, Nasca, Mantle (“The Paracas Textile”), 100–300 C.E., cotton, camelid fiber, 58–1/4 x 24–1/2″ / 148 x 62.2 cm, found south coast, Paracas, Peru (Brooklyn Museum)

When they depicted clothing, Paracas and Nazca artists often added a face, or an animal body to the loose ends of fabric hanging behind a wearer. This artistic convention seems to suggest the lively movements of cloth fluttering behind a wearer, and hints that these ancient people considered cloth a precious carrier of vitality: an interpretation that seems warranted because this vibrant textile gives us such an evocative and animated glimpse into their world.

Backstory

The Paracas Textile is only one of hundreds of similar textiles that originate from multiple burial sites on the Paracas peninsula. These burials were first identified and excavated by the renowned Peruvian archaeologist Julio Tello in the 1920s. For political reasons, Tello was forced to abandon the site in 1930, and, without a team of archaeologists to oversee the area, a period of intense looting followed. It is now believed that a great number of the Paracas textiles in international museum collections were acquired as a result of this looting, which occurred most heavily between 1931 and 1933.

A large group of these illegally acquired textiles is held by the Gothenburg Collection in the Museum of World Culture in Gothenburg, Sweden. The objects were smuggled out of Peru by the Swedish consul in the early 1930s, and donated to the city of Gothenburg. The museum and city fully acknowledge the objects’ illicit provenance, and have been working with the Peruvian government on a plan for their systematic return. As stated on the museum website,

Large quantities of Paracas textiles were illegally exported to museums and private collections all over the world between 1931 and 1933. About a hundred of these were taken to Sweden and donated to the Ethnographic Department of Gothenburg Museum. Today, problems associated with looted artifacts and illicit trade in antiques are better acknowledged and being addressed.

Though Peru began lobbying for repatriation in 2009, Gothenburg has been somewhat slow to respond to the requests, partly due to the fragile condition of the textiles. According to the museum website, even the transport of these objects between the museum’s archives and their exhibition space in Sweden—a distance of only a few kilometers—has resulted in their deterioration. Despite these concerns, a plan has been put in place to systematically return some of the textiles to Peru. The first four were delivered in 2014, and another 79 in 2017. Further works are set to be returned by 2021. The repatriated textiles are now in the possession of Peru’s General Directorate of Museums of the Ministry of Culture.

The case of the Gothenburg Paracas textiles highlights the need not only for governmental and institutional agreements regarding the restitution of illegally acquired objects, but also for oversight concerning the continued stewardship and preservation of these fragile artworks.

Backstory by Dr. Naraelle Hohensee