A truly modern architecture

What is impractical can never be beautiful. Otto Wagner

Functionalist design

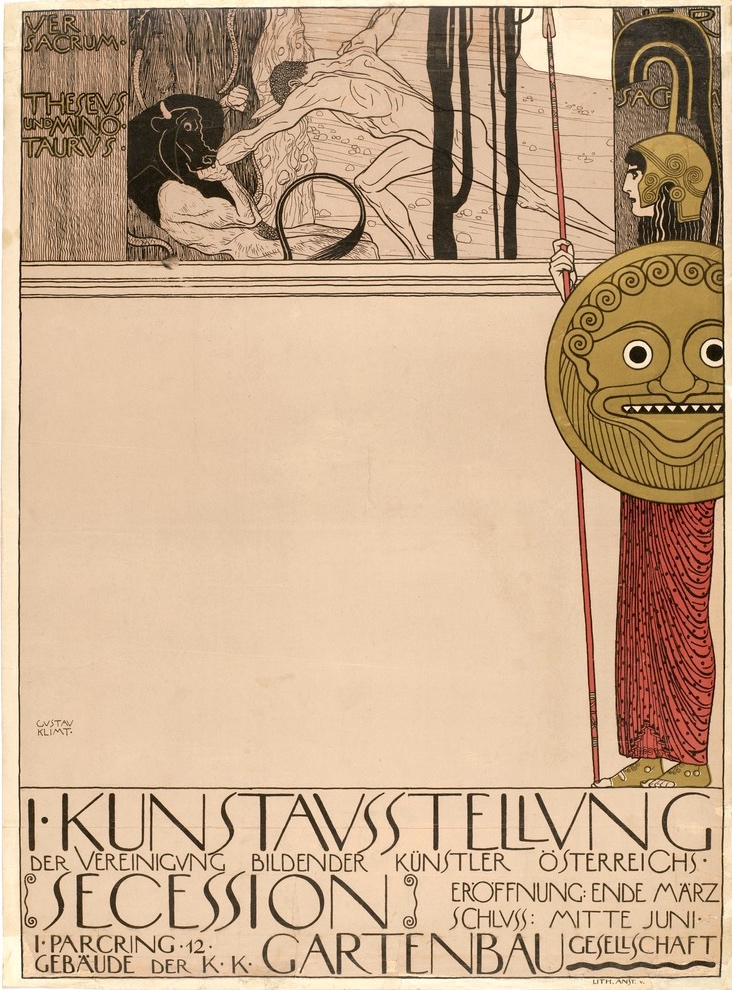

Wagner’s approach to design was closely tied to that of the Secession—a progressive group of Austrian artists, architects and designers who pursued artistic rejuvenation in combining quality building processes with new materials and technologies, and expressive modernist forms. Secessionist architects, including Josef Hoffmann and Joseph Maria Olbrich, were drawn to the idea of Gesamtkunstwerk—or the “total work of art”—in which all aesthetic elements are subordinated to the whole effect. In practice, this concept promoted artistic craftsmanship across a wide spectrum of disciplines and favored collaborative models of creation over individual authorship. In 1903, the craftsmen cooperative called the Wiener Werkstätte (Vienna Workshop) was developed by a group of Secessionists to facilitate this end. Bringing together designers of fashion, furniture and books, with architects, sculptors, painters, ceramists, and jewelers, the Werkstätte elevated the status of the craftsman while at the same time facilitating the unification of artistic endeavors in single fully-designed products.

Plan

Materials and furnishings

Materials were selected due to their durability, economy and functionality. For the flooring, glass-block, porcelain tile and linoleum was laid over asphalt to create insulated, easily cleaned and long lasting surfaces. In high traffic areas, marble wall paneling thwarts wear and prevents the need for repainting, and aluminum hot-air blowers are not only sleek and sanitary, but occupy minimal floor space.

The bank’s furniture and detailing were also under Wagner’s purview and he developed an entire catalogue of standard-design furnishings that allowed for maximum economic and functional flexibility, depending on the respective location and use of each piece. With the exception of the chief executive’s office—where brass, velour and mahogany was used in the furniture—light fixtures were made of aluminum, porcelain and nickel, and the wood used in desks, cabinets, counters and chairs was artfully-treated beech.

Backstory

When it was built at the turn of the last century, Otto Wagner’s building appeared strikingly modern compared to the baroque architecture that characterized most of central Vienna at the time. Today, though, it makes up part of the historic urban fabric that led UNESCO to inscribe the city’s center into the World Heritage List in 2001:

…its architectural and urban qualities and layout…illustrate [Vienna’s] three major phases of development—medieval, Baroque, and the Gründerzeit—that symbolize Austrian and central European history. The Historic Centre of Vienna has also maintained its characteristic skyline.

It is Vienna’s skyline that is now a cause for concern by UNESCO and others. A project by a private developer to create a hotel, conference center, and ice rink on the edge of the city’s historic district prompted UNESCO to put Vienna on its List of World Heritage in Danger in 2017. The design for the hotel entailed the remodeling of an existing International Style tower that was built in 1964, as well as the construction of an additional apartment tower that exceeded the average height of the surrounding buildings (though it still complied with the city’s planning rules). UNESCO and ICOMOS strongly condemned the project, as well as the city’s new planning policies with regard to height limits, drawing on the language of the Vienna Secession to argue for the tower’s incompatibility with the cityscape:

Today, the mass of the Intercontinental Hotel still creates a contrast with the “Gesamtkunstwerk” character of the close surrounding context which, as a manifestation of late 19th century’s architecture, is an attribute of the property “Historic Centre of Vienna.”

The architect and developer, on the other hand, argued that the new plans highlighted important phases of the city’s architectural history:

Like no other part of [historical Vienna], the area surrounded by the Vienna Concert Hall (built in 1913), the Vienna Ice Skating Club (WEV) (established in 1899) and the InterContinental Vienna (built in 1964) documents the (architectural) history of Vienna in the 20th century.

Urban development is a growing threat to cultural heritage around the globe. In some places, sites need strict protections to ensure that historically important structures are not built over or encroached upon by newer ones. However, in this case, UNESCO and other organizations are arguing for something more subtle: the preservation of the historic character of a particular neighborhood. The developer and city planners in Vienna are interested in economic growth, and value the history of 20th-century architecture as a valid part of the city’s story. Organizations like UNESCO (as well as local groups) would prefer to preserve the city as it looked in the nineteenth century and earlier. These differing points of view reveal how “preservation” and “heritage” are not stable concepts: they grow and change over time as societies themselves change. Balancing these ideas—and the tensions between history and modernity—while still allowing for growth is a difficult task faced around the world by city planners and preservationists, not only in high-risk zones, but in wealthy metropolises like Vienna, as well.

Backstory by Dr. Naraelle Hohensee