Great Mosque of Djenné, Mali, 1907 (photo: BluesyPete, CC BY-SA 3.0)

As one of the wonders of Africa, and one of the most unique religious buildings in the world, the Great Mosque of Djenné, in present-day Mali, is also the greatest achievement of Sudano-Sahelian architecture. It is also the largest mud-built structure in the world. We experience its monumentality from afar as it dwarfs the city of Djenné. Imagine arriving at the towering mosque from the neighborhoods of low-rise adobe houses that comprise the city.

Djenné was founded between 800 and 1250 C.E., and it flourished as a great center of commerce, learning, and Islam, which had been practiced from the beginning of the 13th century. Soon thereafter, the Great Mosque became one of the most important buildings in town primarily because it became a political symbol for local residents and for colonial powers like the French, who took control of Mali in 1892. Over the centuries, the Great Mosque has become the epicenter of the religious and cultural life of Mali, and the community of Djenné. It is also the site of a unique annual festival called the Crépissage de la Grand Mosquée (Plastering of the Great Mosque).

Great Mosque of Djenné, Mali, 1907 (photo: Martha de Jong-Lantink, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

The Great Mosque that we see today is its third reconstruction, completed in 1907. According to legend, the original Great Mosque was probably erected in the 13th century, when King Koi Konboro—Djenné’s twenty-sixth ruler and its first Muslim sultan (king)—decided to use local materials and traditional design techniques to build a place of Muslim worship in town. King Konboro’s successors and the town’s rulers added two towers to the mosque and surrounded the main building with a wall. The mosque compound continued to expand over the centuries, and by the 16th century, popular accounts claimed half of Djenné’s population could fit in the mosque’s galleries.

The first Great Mosque and its reconstructions

Some of the earliest European writings on the first Great Mosque came from the French explorer René Caillié who wrote in detail about the structure in his travelogue Journal d’un voyage a Temboctou et à Jenné (Journal of a Voyage to Timbuktu and Djenné). Caillié traveled to Djenné in 1827, and he was the only European to see the monument before it fell into ruin. In his travelogue, he wrote that the building was already in bad repair from the lack of upkeep. In the Sahel—the transitional zone between the Sahara and the humid savannas to the south—adobe and mud buildings such as the Great Mosque require periodic and often annual re-plastering. If re-plastering does not occur, the exteriors of the structures melt in the rainy season. Based on Caillié’s description, his visit likely coincided with a period when the mosque had not been re-plastered for several years, and multiple rainy seasons had probably washed away all the plaster and worn the mud-brick.

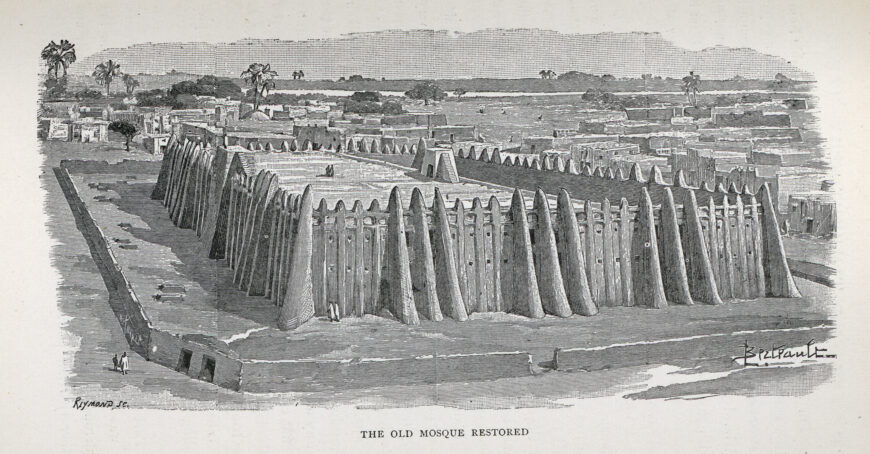

“The Old Mosque Restored,” from Félix Dubois, Timbuctoo the Mysterious (London: William Heinemann, 1897), pp. 157 (Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.)

A second mosque built between 1834 and 1836 replaced the original and damaged building described by Caillié. We can see evidence of this construction in drawings by the French journalist Félix Dubois. In 1896, three years after the French conquest of the city, Dubois published a plan of the mosque based on his survey of the ruins. The structure drawn by Dubois was more compact than the one that is seen today. Based on the drawings, the second construction of the Great Mosque was more massive than the first and defined by its weightiness. It also featured a series of low minaret towers and equidistant pillar supports.

The present and third iteration of the Great Mosque was completed in 1907, and some scholars argue that the French constructed it during their period of occupation of the city starting in 1892. However, no colonial documents support this theory. New scholarship supports the idea that the mason’s guild of Djenné built the current mosque along with the labor of enslaved people from villages of adjacent regions, brought in by French colonial authorities. To accompany and motivate the enslaved laborers, musicians were provided who played drums and flutes. Enslaved laborers included masons who mixed tons of mud, sand, rice-husks, and water and formed the bricks that shape the current structure.

Roof (detail), Great Mosque of Djenné, Mali, 1907 (photo: United Nations Photo, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

The Great Mosque today

Ostrich egg at the top of the Great Mosque of Djenné, Mali, 1907 (photo: BluesyPete, CC BY-SA 3.0)

The Great Mosque that we see today is rectilinear in plan and is partly enclosed by an exterior wall. An earthen roof covers the building, which is supported by monumental pillars. The roof has several holes covered by terra-cotta lids, which provide its interior spaces with fresh air even during the hottest days. The façade of the Great Mosque includes three minarets and a series of engaged columns that together create a rhythmic effect.

At the top of the pillars are conical extensions with ostrich eggs placed at the very top—symbol of fertility and purity in the Malian region. Timber beams throughout the exterior are both decorative and structural. These elements also function as scaffolding for the re-plastering of the mosque during the annual festival of the Crépissage. Compared to images and descriptions of the previous buildings, the present Great Mosque includes several innovations such as a special court reserved for women and a principal entrance with earthen pillars that signal the graves of two local religious leaders.

Façade (detail), Great Mosque of Djenné, Mali, 1907 (photo: Gilles MAIRET, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Re-plastering the mosque

Interior view, Great Mosque of Djenné, Mali, 1907 (photo: UN Mission in Mali, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

During the annual festival of the Crépissage de la Grand Mosquée, the entire city contributes to the re-plastering of the mosque’s exterior by kneading into it a mud plaster made from a mixture of butter and fine clay from the alluvial soil of the nearby Niger and Bani Rivers. The men of the community usually take up the task of mixing the construction material. As in the past, musicians entertain them during their labors, while women provide water for the mixture. Elders also contribute through their presence on site, by sitting on terrace walls and giving advice. Mixing work and play, young boys sing, run, and dash everywhere.

Over the years, Djenné’s inhabitants have withstood repeated attempts to change the character of their exceptional mosque and the nature of the annual festival. For instance, some have tried to suppress the playing of music during the Crépissage, and foreign Muslim investors have also offered to rebuild the mosque in concrete and tile its current sand floor. Djenné’s community has unrelentingly striven to maintain its cultural heritage and the unique character of the Great Mosque. In 1988, the tenacious effort led to the designation of the site and the entire town of Djenné as a World Heritage Site by UNESCO.

Backstory

The Great Mosque of Djenné is only one of many important monuments in the area known as the Djenné Circle, which also includes the archaeological sites of Djenné-Djeno, Hambarketolo, Tonomba, and Kaniana. The region is known especially for its characteristic earthen architecture, which, as noted above, requires continuous upkeep by the local community.

Djenné’s unique form of architecture also makes it particularly susceptible to environmental threats, especially flooding. The town is situated along a river, and in 2016, torrential rains led to massive floods that caused one historic 16th-century palace to collapse, and left the Great Mosque with significant cracks its pillars. Construction of new buildings on the archaeological sites and inadequate waste disposal infrastructure also present continual problems.

UNESCO and other agencies have supported the restoration of the riverbanks in Djenné to help prevent flooding, and the four archaeological sites have now gained official status as properties of the state, which shields them from urban development. However, the conservation situation in Djenné remains fragile. Since the civil war in Northern Mali in 2012, the government has had limited bandwidth to deal with all of the various measures necessary to successfully protect, maintain, and monitor these sites. UNESCO has also noted a lack of funding from outside partners, who, according to the agency, have shown greater interest in Timbuktu, where terrorists vandalized several historic mausoleums and a mosque in 2012.

The current state of Djenné highlights the complex network of factors that affect world heritage: armed conflict and civil unrest, environmental threats, urban development, and lack of cooperation between agencies can all undermine the fate of monuments like the Great Mosque. Such circumstances remind us of the importance and the difficulty of conservation efforts not just in Djenné, but around the globe.

Backstory by Dr. Naraelle Hohensee

Additional resources

Archnet Digital Library on the Great Mosque of Djenné Restoration

Katarina Höije, “The mud mosque of Mali” from Roads and Kingdoms

Old Towns of Djenné (from UNESCO)

UNESCO State of Conservation report for the Old Towns of Djenné