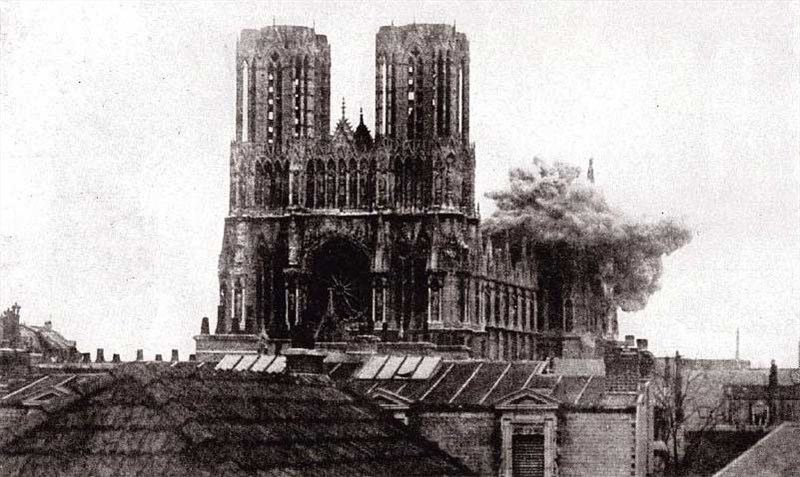

Shell bursting on the cathedral at Reims, from Collier’s New Photographic History of the World’s War, 1918

Have you seen the phrase “Culture in Crisis?

In recent years, particularly since the rise of ISIS’ destructive activities in the Middle East, it’s become common to see articles in the news media as well as in academic journals on the theme of “cultural heritage in crisis.” You could say it’s a booming field.

But how true is it?

It’s certainly true that cultural heritage is in danger of destruction, looting, or illicit trafficking in many places around the world. It’s also true that new types of threats to cultural heritage have developed in the last few decades.

They include,

- the easier movement of goods across national borders via online marketplaces like eBay

- the spread of global banking

- the outbreak of war and other forms of political instability and poverty

- the widespread availability of heavy machinery and explosives

Some regions—most recently the heritage-rich areas of the Middle East—have certainly experienced a marked increase in illicit trafficking in the context of ongoing political upheavals and conflicts.

But usage of the term “crisis” to describe the destruction of cultural heritage around the world is perhaps a misleading one. “Crisis” is a term that indicates a problem that has an urgent, yet temporary quality. However, the loss and destruction of cultural heritage is not new in human history and is not restricted by the duration of political instability in faraway lands. Many regions of the world, including the United States, face a longstanding and ongoing struggle to protect heritage in the face of numerous challenges, regardless of political, social, or economic security. It may be worth considering that the idea of “crisis” deceptively frames the destruction of heritage as a product of temporary instabilities that cease to be a problem once conflicts are over. In reality, conditions of “crisis” only really provide new opportunities for heritage destruction processes that were already happening and will continue happening after the “crisis” is over.

War

Let’s take a closer look at these processes. Broadly speaking, there are two types of threats:

- destruction of heritage sites and objects caused by war, poverty, and development initiatives

- the looting and trafficking of objects that frequently arises out of those contexts

In wartime, destruction of heritage sites can be a result of collateral damage, for example, when a bomb targeting one location inadvertently hits another; or it can be the result of intentional damage, aimed to demoralize and insult the values and religious and cultural symbols of an enemy. It is often difficult to distinguish between collateral and intentional damage, and perpetrators may claim deliberate destruction was an accident in an attempt to avoid prosecution. In the Syria conflict, for example, you’ve probably heard about the destruction caused by ISIS. However, the majority of damage to cities and to heritage has in fact not been caused by ISIS, but by the Syrian government’s campaign of relentless aerial bombardment, which has destroyed up to 70% of the fabric of the ancient city of Aleppo, a UNESCO World Heritage site.

Walter Hahn, Dresden: view of the destroyed inner city from the town hall tower with sculpture, 1945 (CC BY-SA 3.0 DE)

And though it’s easy to demonize a regime in a country far away, it’s important to remember that similar levels of destruction were caused by both the Axis powers and the Allies in World War II—for the Allies, most famously in Dresden, where a British and American aerial campaign in 1945 left more than 70% of the city in ruins. The neglect of the occupying U.S. forces in Iraq in 2003 famously led to the looting of the National Museum of Iraq, with thousands of objects lost, only half of which have returned, as well as the burning and destruction of Iraq’s magnificent national library, including hundreds of priceless manuscripts dating back to the 16th century. Deliberate or neglectful destruction of heritage has long been a key strategy of war, and perpetrators are rarely prosecuted for it.

The long history of the destruction of heritage shows us that the elimination of culture has always been viewed as a powerful tool of domination and as a key strategy for eliminating the value humans accord to their lives. In recent years, the destruction of heritage—whether through war, commercial exploitation, and/or looting—has been defined by UNESCO as a form of cultural cleansing. In taking human lives, oppressors erase the existence of individual people: but in destroying culture, the memory and identity of entire peoples are erased. It is not surprising to note, therefore, that the destruction of heritage is often a precursor to genocide. This is because in denying people their past, perpetrators also deny them a future.

Crowds in Venice (photo: Gary Bembridge, CC BY 2.0)

Development, climate change, tourism, and natural disasters

Nevertheless, wartime destruction of heritage is only a small fraction of the overall loss of cultural heritage around the world. Much more significant and long-lasting is destruction due to urban development, mineral and resource extraction, climate change, tourism, and even natural disasters. For example, the ancient Buddhist site of Mes Aynak in Afghanistan is now threatened by Chinese mining interests, a situation made famous in a recent documentary. Similarly, the push to expand resource extraction on public lands in the United States is also causing widespread loss of heritage, as at the Bears Ears National Monument, which was controversially reduced by 85% in a decision signed by President Trump in December 2017.

Although many heritage sites are preserved in order to encourage tourist revenue, tourism can also cause massive destruction because of the large numbers of people it can attract and also because transforming a site into a tourist-friendly locale often profoundly transforms its meaning for local people, who may find their connections to a place have been erased. Such is the case at Dubrovnik, a city that was reconstructed by an international consortium of donors after the Balkan war and which now finds itself managing a Game of Thrones-inspired tourist influx that threatens to leave little of the original city behind, a destruction that some residents have characterized as worse than that during wartime.

Looting

If destruction of heritage during wartime is akin to a relatively sudden death, looting is like a cancer that slowly erodes it. Looting is the theft of heritage items for sale on the antiquities market, most often to wealthy private buyers in the United States and Europe. As art history professor Nathan Elkins has shown, the consequences of purchasing even small items like coins can be devastating for our knowledge about the past. Once an object is removed from its original environment, it instantly loses much of its ability to convey information about how people once lived.

Pedestal with feet fragments, Prasat Chen, Koh Ker, photo: © Simon Warrack, by permission, all rights reserved

Archaeologists call the environment in which an object is found, its context. Context is the object and its relationship to all the other objects and material in an archaeological site. The relationships between these objects is what enables archaeologists to recreate the past (objects that have been looted, and thereby robbed of this context can be called “ungrounded“). As such, even the smallest objects, such as ancient coins, can provide powerful evidence about the lives of people in the past. While locals are often blamed for looting, it is important to point out that local looting is often subsistence looting—looting carried out to supplement meagre incomes—and that it is only profitable because it responds to demand in wealthy countries. The antiquities market is vast, and as the Wall Street Journal reported last year, it has consequences far beyond just loss of our knowledge about the past, since much like drug trafficking, its profits fuel terrorism, criminal enterprises, and many other forms of criminal activity.

What can be done?

In repositioning the discussion of the “current crisis” to a discussion of how we are in fact currently experiencing the latest iteration of a long-standing problem with global reach, we can avoid simplistic solutions that propose that squashing the “bad guys”—for example, ISIS—will solve the destruction and looting problem once and for all. Most importantly, it allows us to focus on the real driver of destruction: the demand in wealthy countries for heritage objects—a demand that ultimately fuels the entire antiquities trade—and the lax legislation that enables that trade to flourish. It also permits a conversation about related issues, for example the lack of public education about the antiquities trade, or problematic distinctions such as that between art—largely considered to be a private commodity subject to market demand, versus heritage—which is typically framed as “universal” and the patrimony of all.

Understanding that cultural heritage has been under threat for a very long time allows us to avoid short-term, crisis-based responses, and enables us to craft long-lasting, systemic solutions.