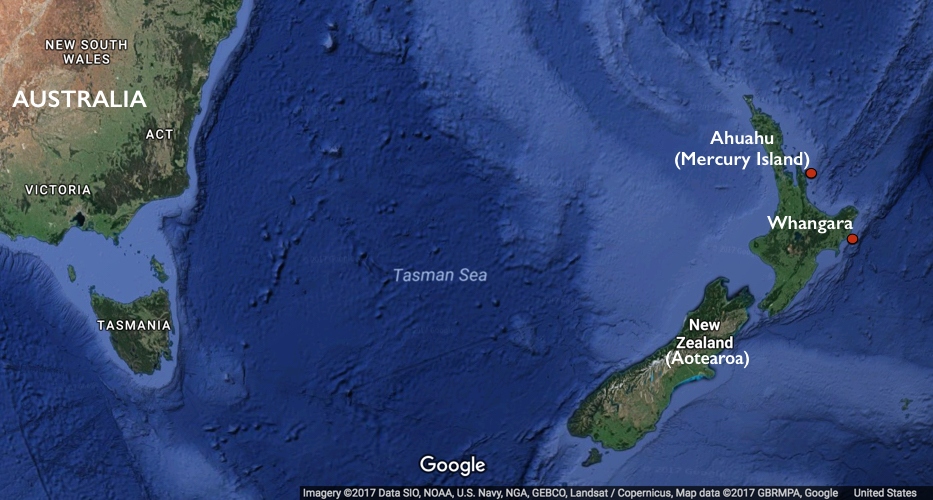

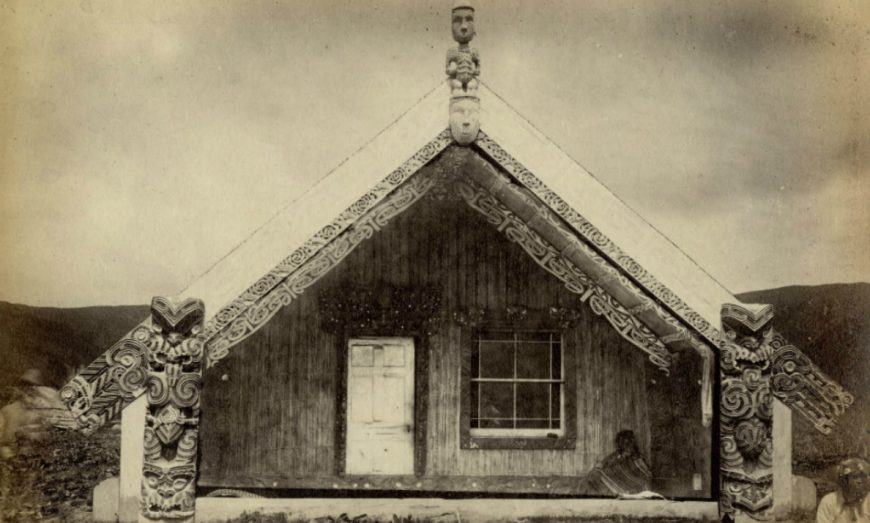

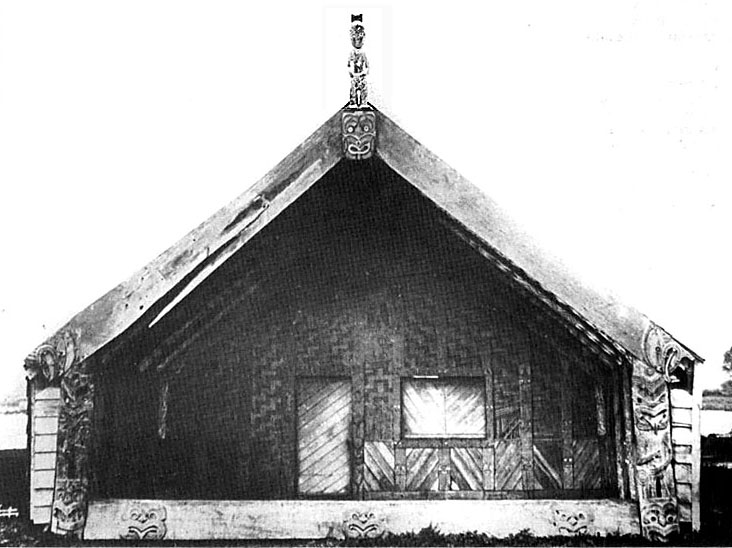

Photograph showing Paikea in its original location atop the Māori meeting house, Te Kani a Takirau, Uawa, Aotearoa (New Zealand)

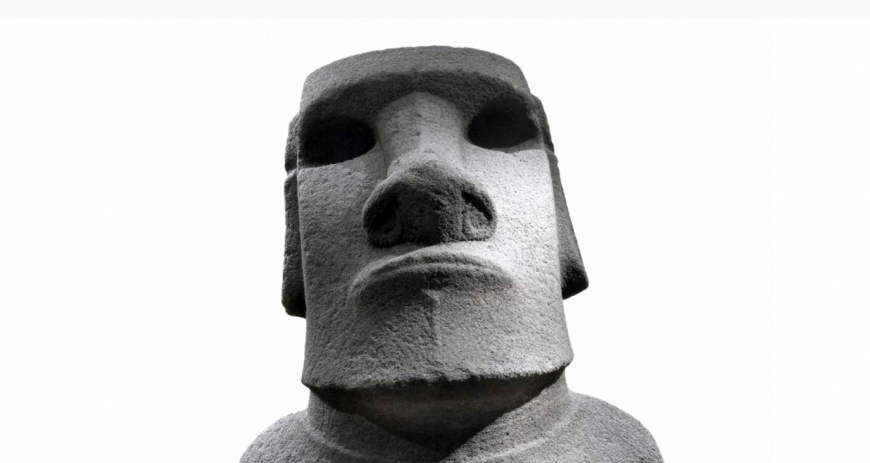

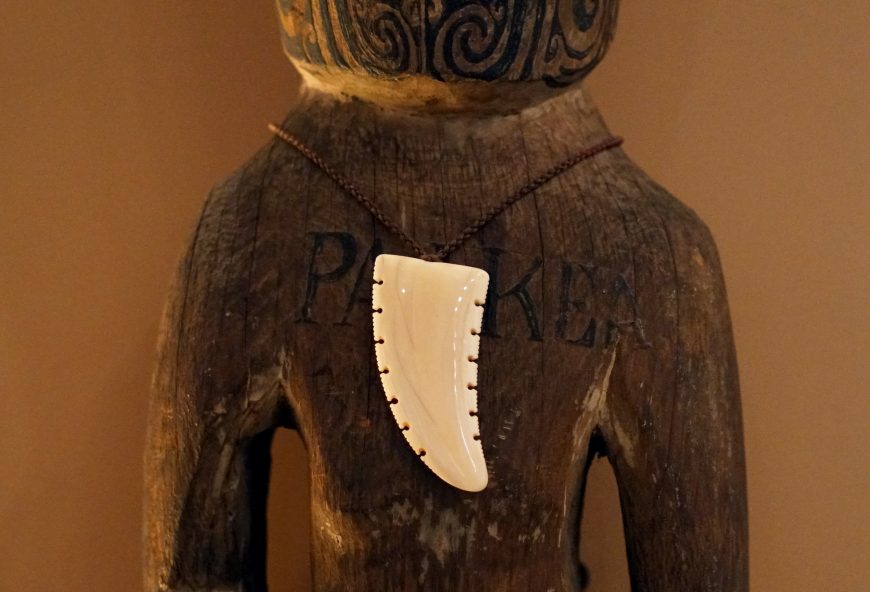

Paikea, 19th c., wood, pigment, 64x42x19cm, photo: Jennifer Steffey, courtesy AMNH

During the nineteenth and the first half of the twentieth century, the trade in ethnic artifacts was rife, particularly where territories had been colonized by European powers. Thousands of artifacts of all descriptions from across the Pacific were traded legally and illegally, and many now reside in museums, private collections, and other institutions throughout the world—including an important sculpture of a Māori ancestor named Paikea (pronounced pie-kee-ah)

The Whale Rider

Paikea was an important ancestor of the Māori tribes in Uawa (Tolaga Bay) on the East Coast of the North Island of Aotearoa (New Zealand). He survived a marine disaster in the ancient Hawaiki homeland of the Māori in the Pacific Ocean, by invoking, through incantation, the denizens of the deep sea to come to his rescue and take him ashore. Paikea eventually made landfall at Ahuahu (Mercury Island) in Aotearoa (New Zealand). After several excursions to the south-east, Paikea eventually made his way to the mouth of the Waiapu River on the East Coast, married Huturangi, and settled at Whangara. He is more popularly known throughout the world as “The Whale Rider,” from the movie of the same name.

For his many descendants, Paikea is a key link to the ancient Hawaiki homeland, as well as to the marine stories and body of seafaring knowledge, and to the tribal settlements on the eastern seaboard of both islands of Aotearoa (New Zealand). He is honored through songs, genealogy, stories, dances, novels, film, and art.

A house and a dance

Paikea’s descedant, Te Kani a Takirau, was born 23 generations later, in about 1790. He was regarded throughout Māoridom as a leading ariki, a noble high-ranking person of his time. After Te Kani a Takirau’s death in 1856, a carved house was built by his people at Uawa, and named after him (see photograph at the top of the page). The carved figure on top was named Paikea, and notable orators composed a haka (posture dance) for this occasion:

| Uia mai koia whakahuatia ake | If it is asked |

| Ko wai te whare nei e? | What is the name of this house? |

| Ko Te Kani | It is Te Kani |

| Ko wai te tekoteko kei runga? | Who is the figurehead on top? |

| Ko Paikea, ko Paikea | It is Paikea, it is Paikea |

| Whakakau Paikea | Paikea transformed |

| Whakakau he tipua | Into an amazing being |

| Whakakau he taniwha | Into an awesome being |

| Ka ū Paikea ki Ahuahu, pakia! | And Paikea did come ashore at Ahuahu! |

| Kei te whitia koe ko Kahutiaterangi | Do not mistake him for Kahutiaterangi |

| E ai tō ure ki te tamahine a Te Whironui | He cohabited with the daughter of Te Whironui |

| Nāna i noho Te Rototahe | And resided at Te Rototahe |

| Auē, auē he koruru koe, e koro e! | You are there sire as the figurehead! |

Since that time, six generations of Paikea’s descendants have performed this haka. For the past four generations it has also been performed as a waiata ā-ringa, an action song. In the last two generations it has developed into a novel—The Whale Rider, by Witi Ihimaera—which became the basis for the movie of the same name. This legacy now centers on another house: Whitireia at Whangara, on top of which Paikea sits on his whale. Children who are born into the legacy of Paikea “absorb” the haka and the waiata ā-ringa while growing up, performing it with peers, parents, and grandparents. It is a tribal marker, a rallying call, an expression of pride, and a reminder of our origins.

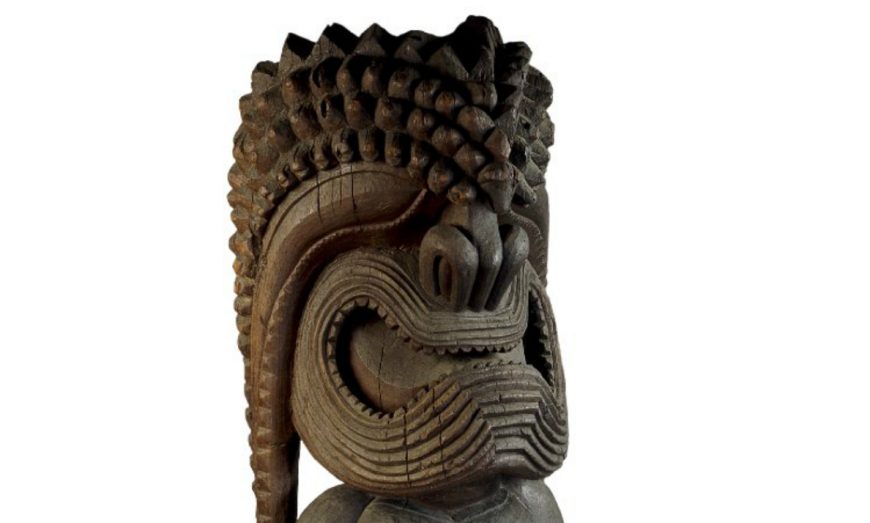

Documentary photograph of the Major-General Robley purchase, 1908 (Paikea is on the right), photo: Thomas Lunt, courtesy of the American Museum of Natural History

A century in storage

In 1908, the American Museum of Natural History acquired the Te Kani a Takirau Paikea from Major General Horatio Robley (British Army), a colonial collector of the time. Paikea was eventually placed on a storage shelf until 2013 when a small group of Paikea’s descendants of Te Aitanga a Hauiti, the tribe of Uawa, arranged a visit to the museum for the purpose of reconnecting with this ancestor figure—part of a bigger plan to reconstruct the house Te Kani a Takirau, physically or digitally.

With Paikea at the American Museum of Natural History, 16 April 2013, photo: Dr. B. Lythberg (the author is standing second from the left wearing a dark shirt)

It was an emotional visit: a mix of tearful reunion, immense pride and melancholy reflection. Coincidentally, the visit occurred at the same time as the Whales (Tohorā) exhibition at the museum, which allowed us to share our Paikea stories with members of the public, museum professionals, students, and others.

A token of love

Our parting with Paikea at the end of the week was difficult and tearful. As is our tradition, we left a gift with him as a token of our love: a carved whale tooth pendant sourced originally from a bull sperm whale that beached at Mahia in northern Hawkes Bay, New Zealand in 1967, which we secured around his neck. In doing so, we unknowingly transgressed museum acquisition protocols as well as international laws regarding trade in ivory, although we had done what was tika, or right, in our view. This provided an embarrassing conundrum for the museum curators who had hosted us, and so later that year the whale tooth was returned to us in New Zealand.

Pendant carved by Lance Ngata from the tooth of a bull sperm whale that beached at Mahia in northern Hawkes Bay, New Zealand in 1967

In 2017, as part of filming a documentary series “Artefact” and with the support of Greenstone TV, the American Museum of Natural History, and professional colleagues from Auckland University, we organized to return the whale tooth—legally this time—to Paikea, and make good our initial gift. Again, a small group of young people from Te Aitanga a Hauiti accompanied the whale tooth and once more the occasion, although shorter, was an emotional one. It was also an opportunity to consider repatriation again: both the process and the implications for the museum, and for Paikea’s descendants and their communities as well. This is what we will deliberate on over the next few months as we reflect on our experiences with this icon of our history and symbol of the colonial artifact trade.