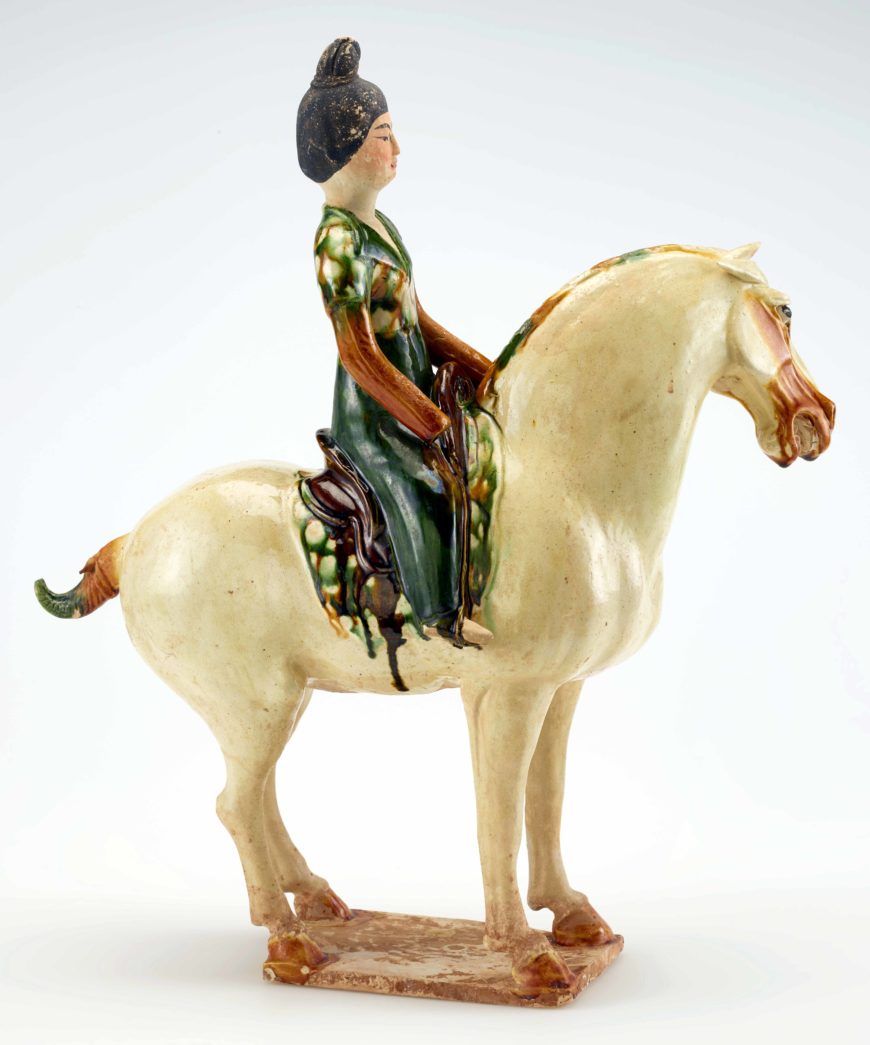

Tomb figure of a woman on horseback, Tang dynasty, c. 700–750, earthenware with lead-silicate glazes and painted details, China, Henan province, possibly Luoyang, 43.1 high x 14.8 x 37.6 cm (Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC: Purchase — Charles Lang Freer Endowment, F1952.13)

The Tang dynasty (618–907) is considered a golden age in Chinese history. It succeeded the short-lived Sui dynasty (581–618), which reunified China after almost four hundred years of fragmentation. The Tang benefited from the foundations the Sui had laid, and they built a more enduring state on the political and governmental institutions the Sui emperors established. Known for its strong military power, successful diplomatic relationships, economic prosperity, and cosmopolitan culture, Tang China was, without doubt, one of the greatest empires in the medieval world.

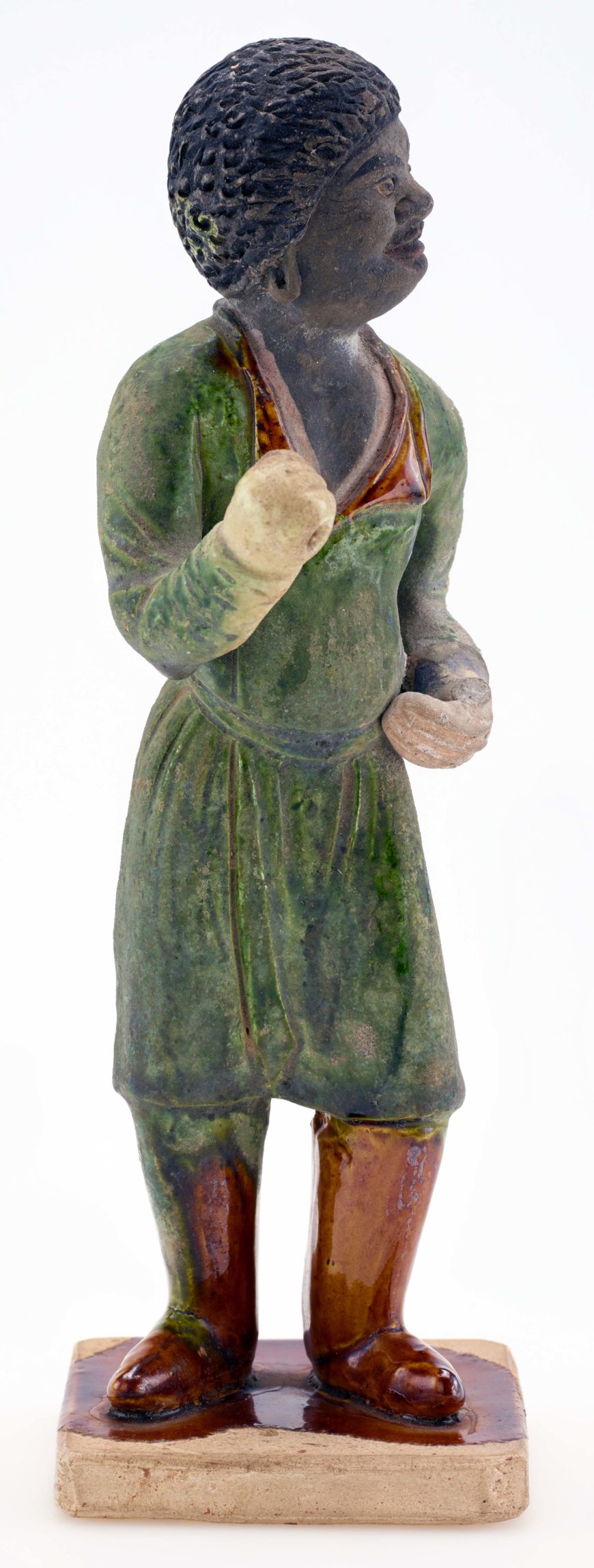

Head of a tomb figure of a Sogdian or Central Asian traveler, Tang dynasty, c. 700–c. 750, ceramic and paint, China, 7 1/2 x 3 9/16 x 4 3/4 in (Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC: The Dr. Paul Singer Collection of Chinese Art of the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; a joint gift of the Arthur M. Sackler Foundation, Paul Singer, the AMS Foundation for the Arts, Sciences, and Humanities, and the Children of Arthur M. Sackler, S2012.9.3603)

During the Tang dynasty, China stretched its territory (including the protectorate states) from the Korean peninsula in the east, to the steppes of Mongolia in the north, to present-day Afghanistan in the west, and to northern Vietnam in the south. Tang secured peace and safety on overland trade routes—the Silk Road—that reached as far as Rome. Merchants, diplomats, and pilgrims came from all over East and Central Asia. They brought with them new religions, ideas, and cultural practices that were eagerly embraced by Tang elite circles. The two capital cities of Chang’an and Luoyang were flooded with foreigners from different parts of the world.

Detail of textile with floral medallions and lozenges, mid-Tang dynasty, first half of the 8th century, brocade (jin): woven silk (weft-faced compound twill), China, 150.1 high x 59.3 cm (Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC: Gift of Charles Lang Freer, F1911.597a-b)

This confident cosmopolitanism is reflected in all the arts of Tang China. The constant exchange of goods along the Silk Road, such as textiles, metalwork, and glassware, inspired Tang craftsmen to experiment with novel techniques, shapes, and designs.

Sancai tomb figure of a man on horseback, Tang dynasty, c. 700–750, earthenware with lead-silicate glazes and painted details, China, Henan province, possibly Luoyang, 39.5 high x 11.7 x 34 cm (Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC: Purchase — Charles Lang Freer Endowment, F1952.12)

One of the most typical and well-known Tang ceramics are the “three-colored” glaze (sancai) wares. Energetically modeled and brightly colored, Tang sancai wares are thought to have been reserved for burial use. Sancai tomb figurines gave a vivid picture of daily life in Tang times.

Tomb figure of a groom, Tang dynasty, c. 700–750, earthenware with lead-silicate glazes and painted details, China, 20.7 x 6.7 cm (Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC: Purchase — Charles Lang Freer Endowment, F1952.14)

Bactrian camels, horses with riders, as well as foreign servants, merchants, and musicians were all popular subjects. Tang potters also experimented with and developed the skills in making single color wares, including white ware and green-glazed celadons, which laid the groundwork for the Song dynasty’s taste in ceramics.

Wu Daozi, detail of Eighty-Seven Immortals, 8th century (Tang dynasty), handscroll, ink on silk, 30 x 292 cm (Xu Beihong Memorial Museum, Beijing)

Wu Daozi, Eighty-Seven Immortals, 8th century (Tang dynasty), handscroll, ink on silk, 30 x 292 cm (Xu Beihong Memorial Museum, Beijing)

Tang painting prospered, partly thanks to the patronage of the Tang court. Painters from all over the empire were attracted to the court. Figure painting thrived during this period. Famous court painters established themselves with their masterful drawing skills. For example, Yan Liben (c. 601–673) was known for his rich and glowing colors and delicate details; while Wu Daozi (c. 680–759) was famous for his vigorous brushwork.

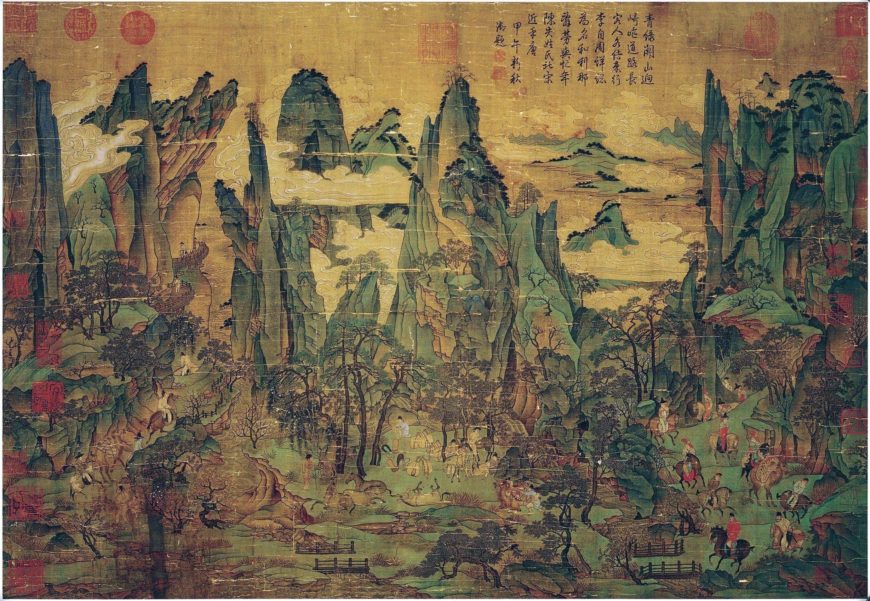

An example of a blue-green landscape. The Emperor Ming Huang Travelling in Shu’, a later 11th-century copy of a Tang dynasty original of the 8th century C.E., painted silk (Palace Museum, Taipei)

Attributed to Wang Wei (王維), Snowy Stream (雪溪圖), part of a handscroll, ink and color on silk (formerly Manchu Household Collection, Beijing, now lost)

Landscape painting took two directions during the Tang. One was a style of painting known as blue-green landscape developed by the court painters, executed in fine lines with added mineral colors. It may have been inspired by Central Asian painting styles. The other was the monochrome ink painting developed by the poet-painter Wang Wei (701–761). This style was favored by the newly emerging social elite who became government officials through the official examination system. The division between the two styles became more apparent during the Song dynasty (960–1279). Besides their excellent painting skills, many of the cultivated scholar-officials were also great poets and calligraphers. The three arts—painting, poetry, and calligraphy—have since been connected and appreciated as “the three perfections.”

This resource was developed for Teaching China with the Smithsonian, made possible by the generous support of the Freeman Foundation

This resource was developed for Teaching China with the Smithsonian, made possible by the generous support of the Freeman Foundation

Additional resources: