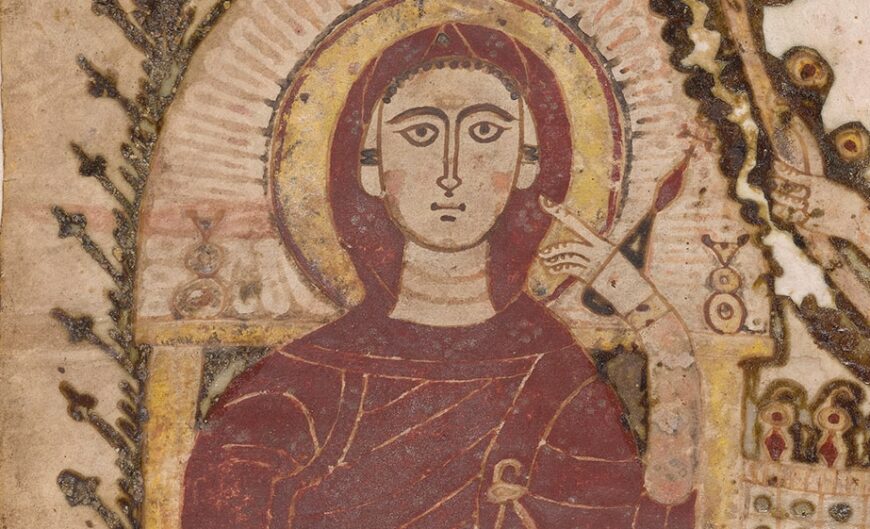

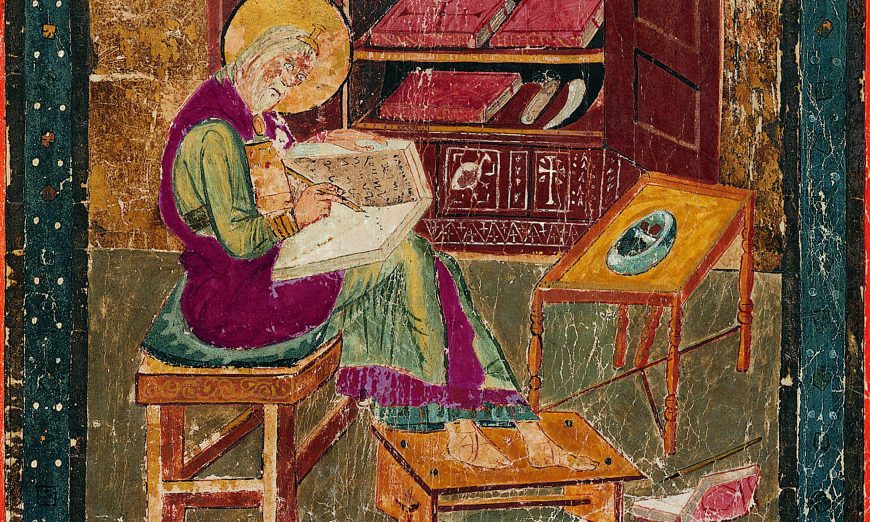

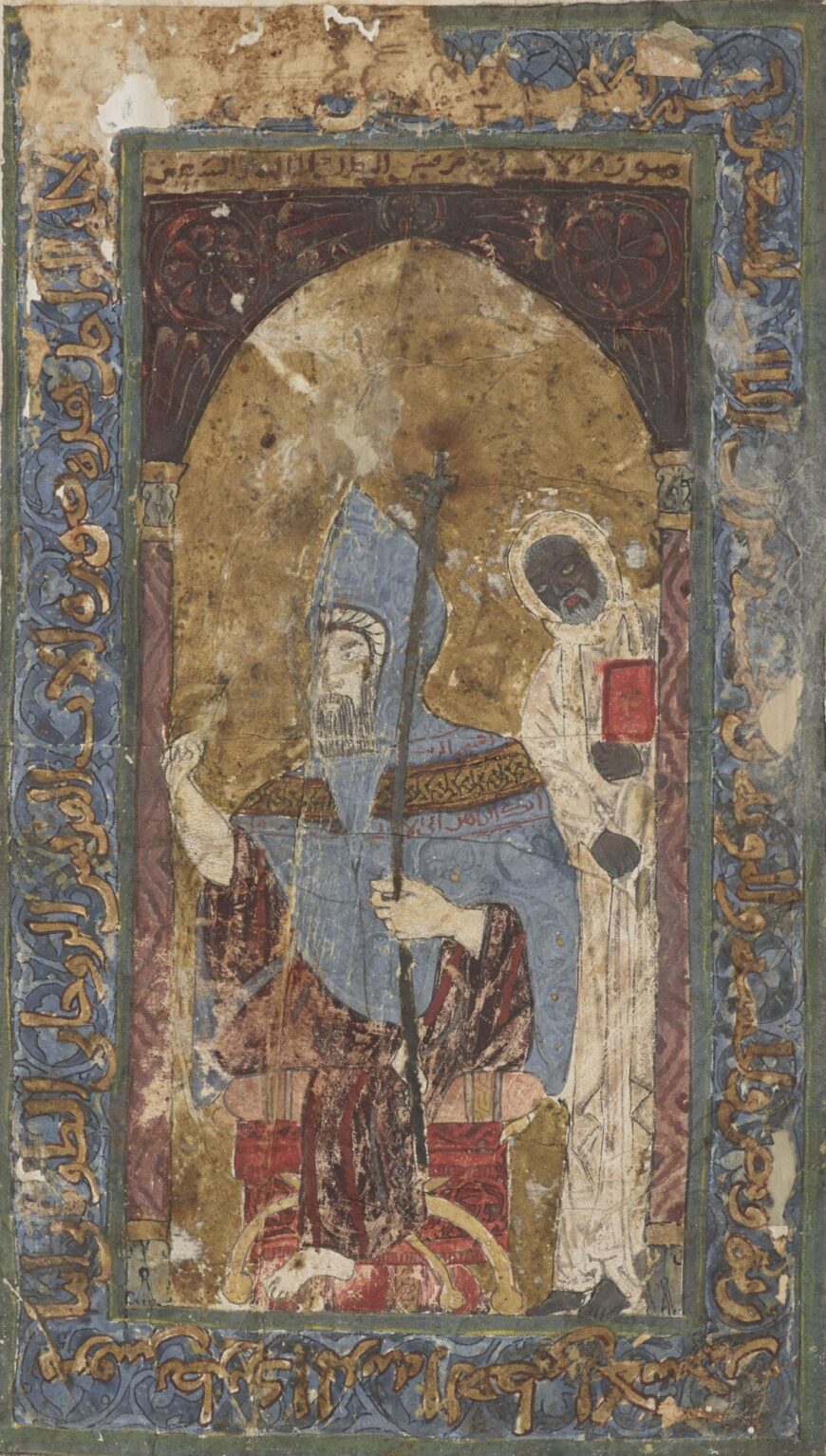

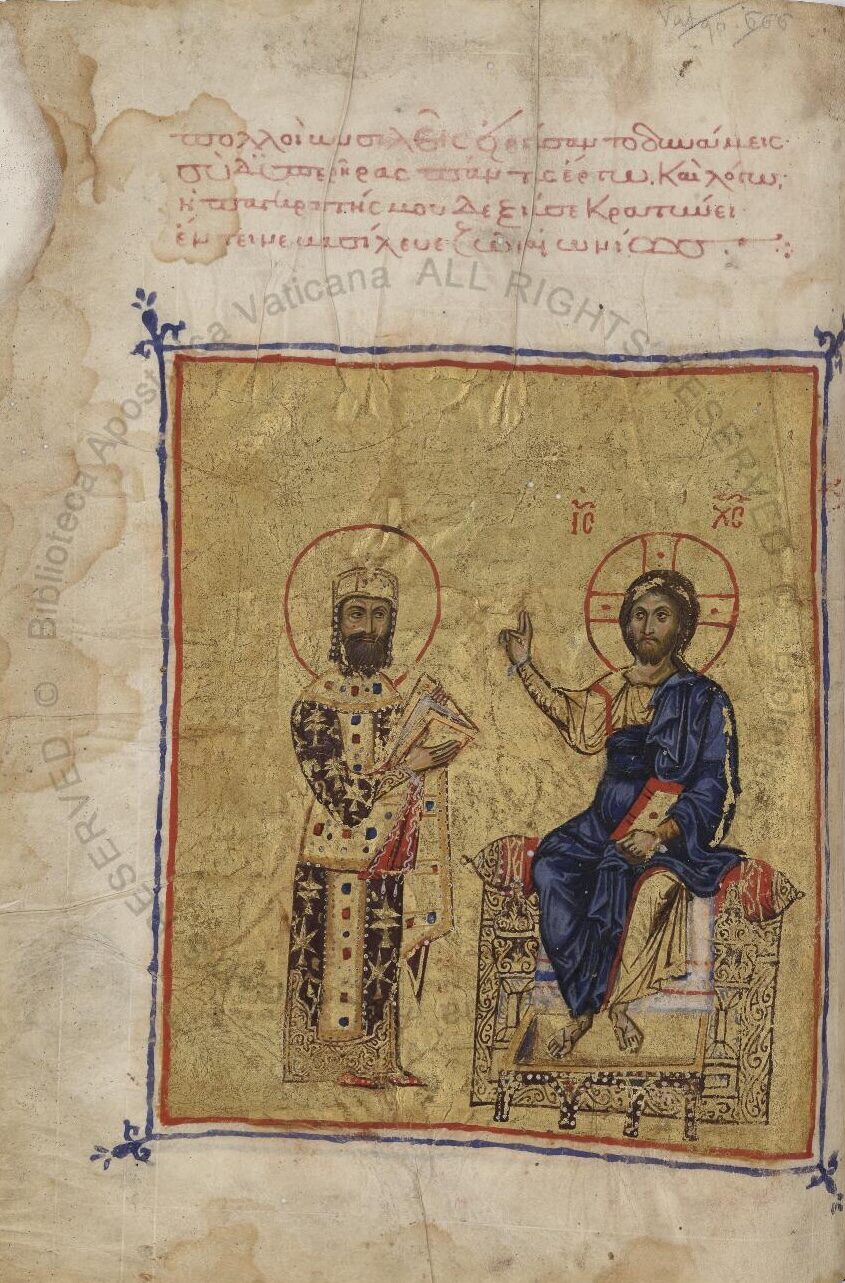

Frontispiece, Patriarch Mark III with attendant, Gospel Book, 1178–80, ink, opaque watercolor, and gold on parchment, 38.5 x 27.5 cm (Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris, MS Copte 13, folio 1 recto)

This frontispiece belongs to a deluxe gospel book from 12th-century Egypt. It depicts the Coptic patriarch Mark III ibn Zurʿa, who led the Coptic Church from 1166 to 1189, seated beneath an arch and flanked by an attendant.

The image is remarkable in several ways: it is the only known extant image of a Coptic patriarch from the Middle Ages; it includes a Black figure; and it appears in one of the most densely illuminated gospel books produced in the eastern Mediterranean during the 12th and 13th centuries. For all of these reasons, this frontispiece deserves a closer look.

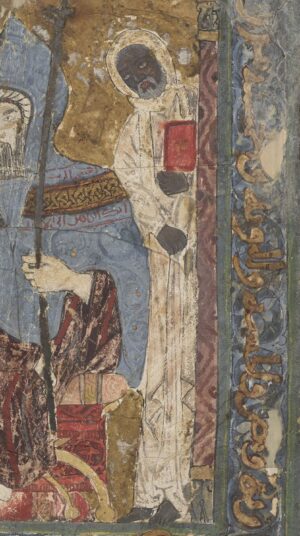

Figures (detail), frontispiece, Patriarch Mark III with attendant, Gospel Book, 1178–80, ink, opaque watercolor, and gold on parchment, 38.5 x 27.5 cm (Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris, MS Copte 13, folio 1 recto)

Coptic patriarchal authority

The frontispiece speaks to the authority of the Coptic patriarch. The patron, Mark III, appears in the splendor of his office, wearing a hooded blue chasuble decorated with gold trim and tiraz over a red robe. He sits in the pose of an Arab governor, with one leg crossed over the other, and holds a benediction cross. The Black man who stands to his side wears the white robes of a priest and holds a red book.

A blue frame decorated with foliate scrolls and overlaid with an Arabic inscription in naskhi script furthers the theme of the portrait.

In the name [of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit:] one God. This is the image of the holy Father, spiritual and blessed, Anba Mark, seventy-third patriarch of the favored city of Alexandria, Egypt, Ethiopia, Nubia, and the Pentapolis [Libya].inscription on frame

The inscription identifies the regions under the spiritual guidance of the Coptic patriarch, which included communities living both in Islamic and Christian states. Having influence beyond Egypt added to the status of the Church.

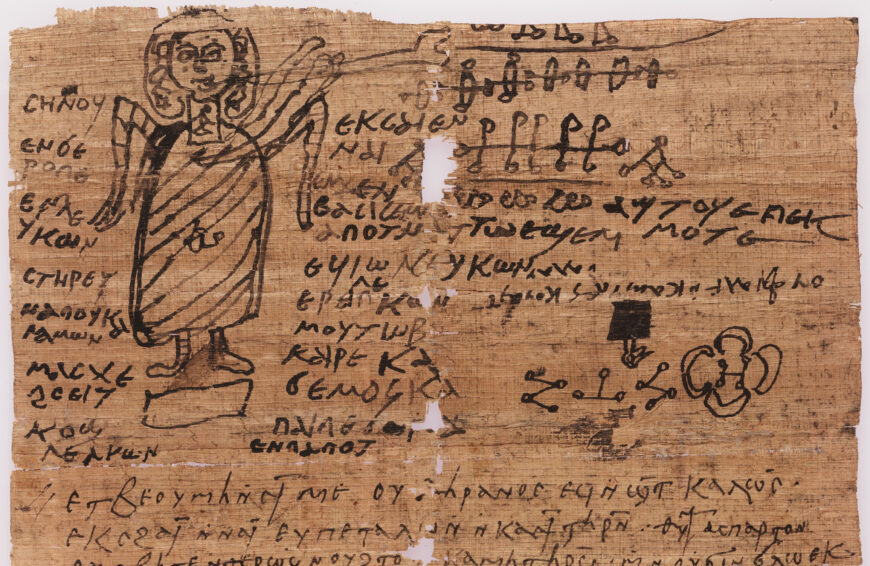

Michael of Damietta and his gospel book

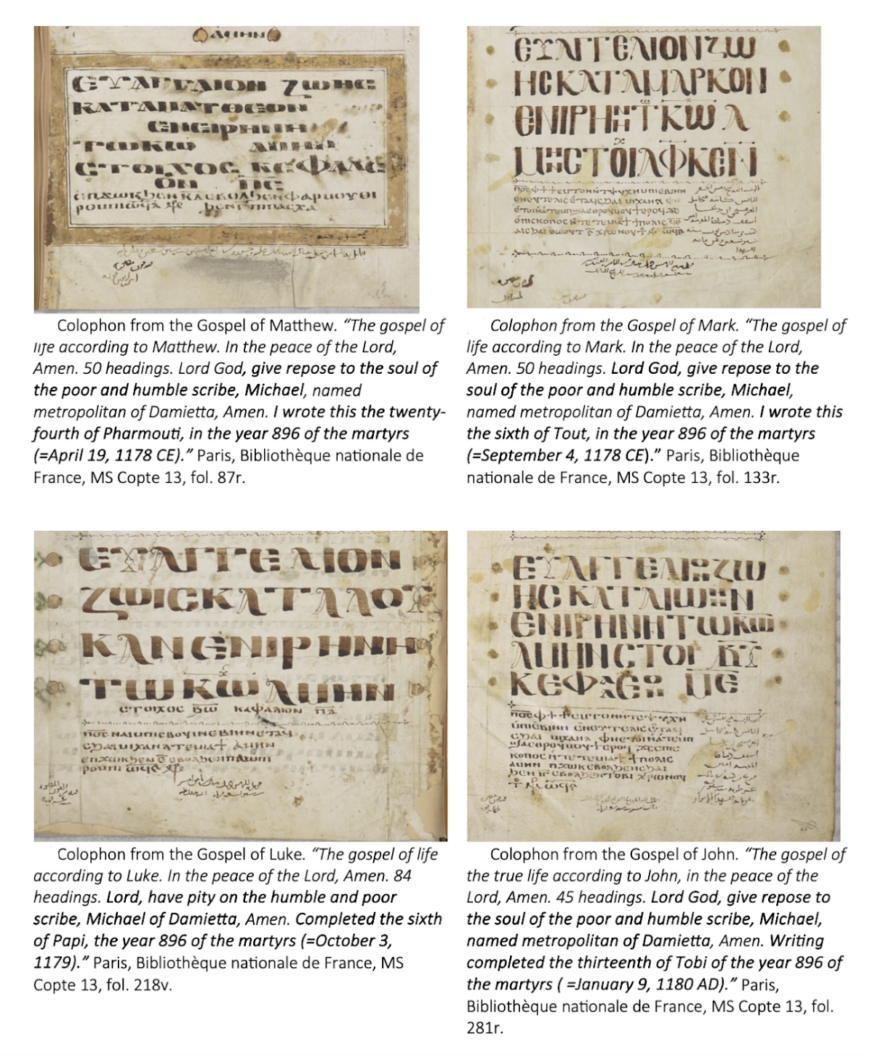

We know a surprising amount about the production of this gospel book, owing to a series of dedicatory inscriptions and colophons that identify the patron and scribe as Michael, metropolitan of Damietta, a port city in northeast Egypt: “In the name of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit: One God. Mīkhā’īl, the poor and humble servant of the Lord and Savior, Jesus Christ, wrote, illuminated, and bound these four holy Gospels.”

Colophon, Gospel of Matthew (folio 133 recto); Colophon, Gospel of Mark (folio 133 recto); Colophon, Gospel of Luke (folio 218 verso); Colophon, Gospel of John (folio 281 recto) (Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris, MS Copte 13)

Michael was the first Coptic bishop in Egypt to be appointed metropolitan, a rank just below that of patriarch. He was a renowned theologian, ecclesiastical politician, and champion of Coptic orthodoxy. Though Michael identifies himself as the scribe, binder, and illuminator of the four gospels, he probably paid for the binding and paintings. However, it is likely that he did act as scribe, since he records the completion of each gospel in bi-lingual Coptic-Arabic colophons, each of which mention his name.

Michael lived during a period of major political transformations. In 1171, Saladin brought an end to the Fatimid dynasty and established a new dynasty in Egypt: the Ayyubids. From an impressive citadel in Cairo (Egypt), Saladin ruled over a diverse population of Muslims, Jews, and Christians. The Copts were the largest of several Christian communities in Egypt, and, under the Ayyubids, they weathered bouts of anti-Christian persecution. Yet Coptic elites also prospered from employment in government bureaus, fostering a burst of artistic productivity that incorporates the traditions of diverse peoples and places.

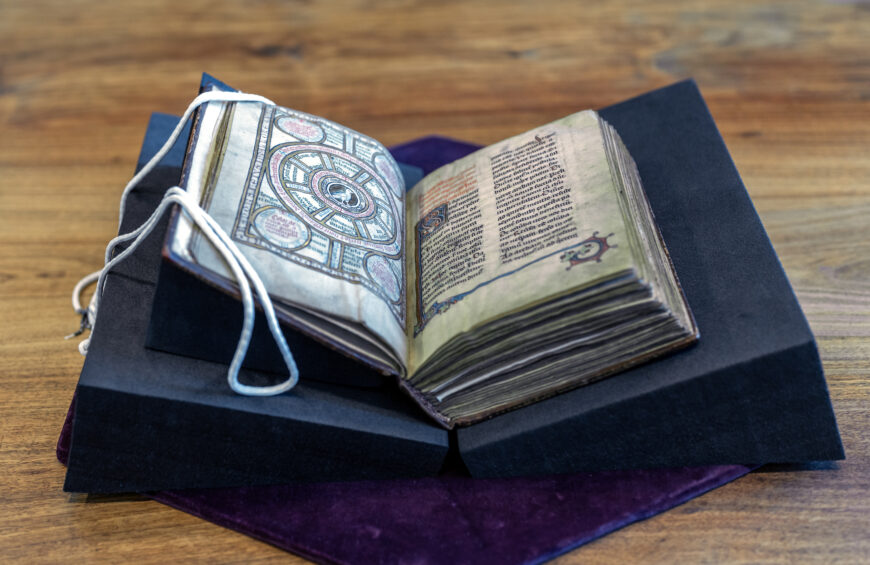

The stunning Coptic artworks of the 12th and 13th centuries are characterized by their high quality and how they transform Byzantine, Islamic, and east Christian visual forms to express specifically Coptic beliefs. Michael’s gospel book is a case in point. Produced from 1178 to 1180, the manuscript contains multiple frontispieces, full-page interlace crosses, and seventy-four narrative paintings executed in brilliant gem-toned hues. Even the pages without narrative scenes have elaborate headings.

The text of the gospels is equally elegant, written in a single column of Bohairic Coptic, the liturgical language of the Coptic Church. Overall, the manuscript is an expression of the taste for illuminated gospels seen across the Christian communities of the Mediterranean during this period.

Mediterranean currents in the frontispiece portraits

Sometime before the 17th century, an owner rebound the manuscript, removing some of its pages and rearranging others. One of its frontispieces is now at the National Museum of Asian Art in Washington, D.C. while another is presumed missing. The rest were rebound with the manuscript.

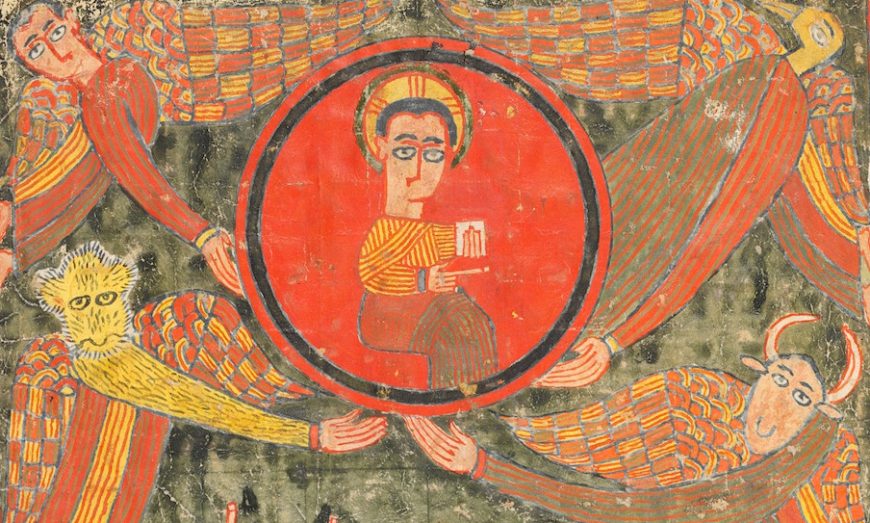

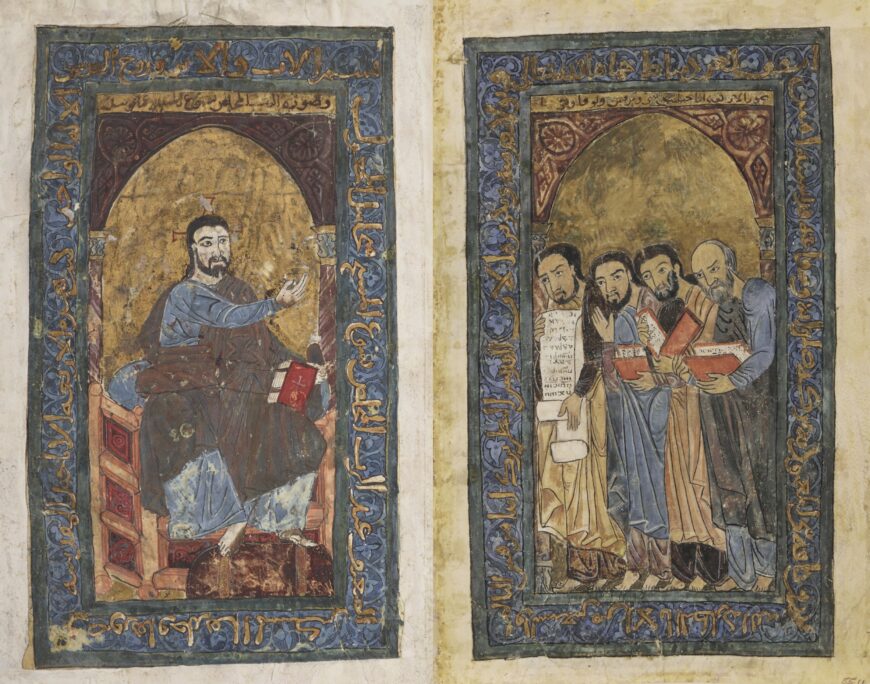

Left: Christ receiving the gospels from the four evangelists, Gospel Book, 1178–80, ink, opaque watercolor, and gold on parchment, 38.5 x 27.5 cm (Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris, MS Copte 13, folio 2 verso); right: Four Evangelists, 1175–1200, opaque watercolor and gold on parchment, 35.6 x 22.8 cm (National Museum of Asian Art, Washington, D.C.)

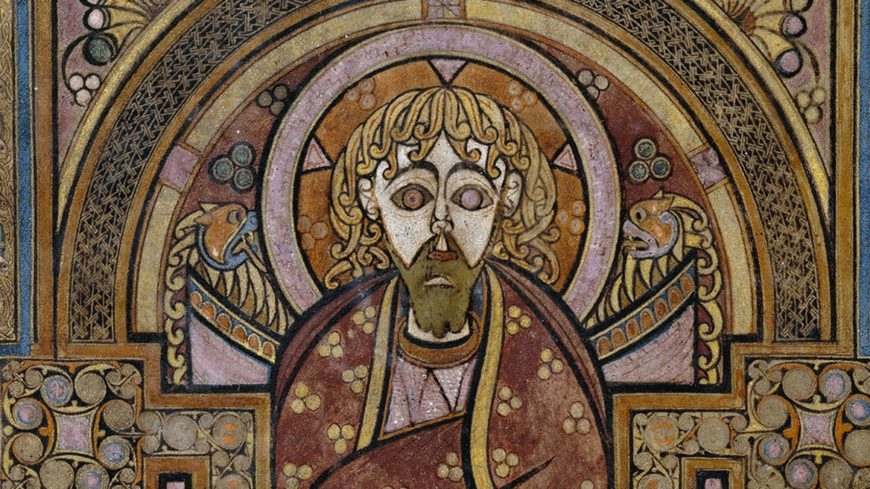

Scholarly consensus holds that the book began (before its rearrangement) with a double portrait, depicting an enthroned Christ beneath an arch, receiving the gospels from the four evangelists (Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John), who line up on the facing page to present him with their completed texts.

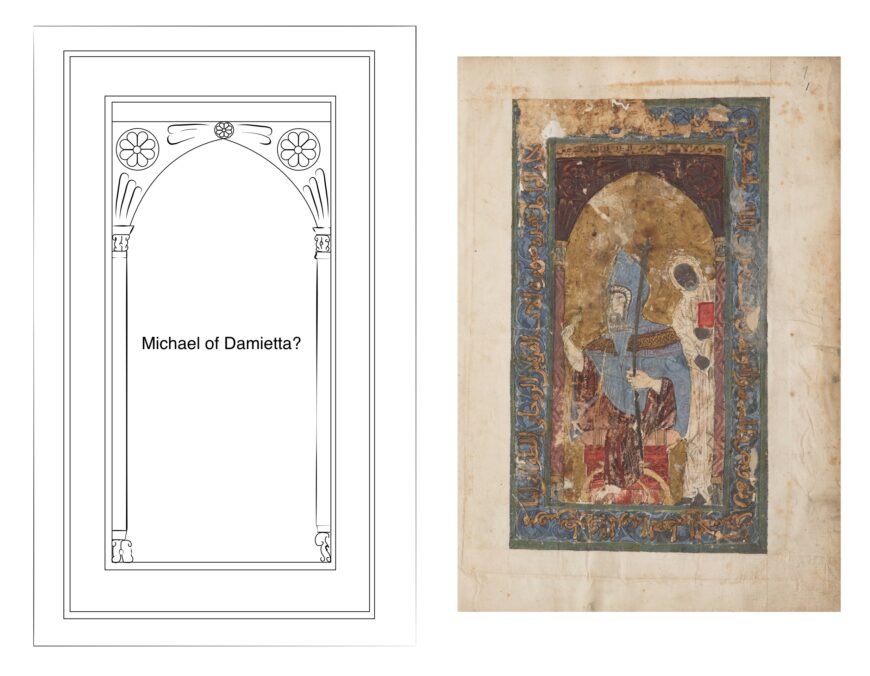

The next bifolium (2-page spread) probably paired an image of the scribe—Michael of Damietta—offering his sumptuous gospel book to Mark III.

Left: Mock-up of missing frontispiece showing the scribe Michael of Damietta; right: frontispiece, Patriarch Mark III with attendant, Gospel book, 1178–80, ink, opaque watercolor, and gold on parchment, 38.5 x 27.5 cm (Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris, MS Copte 13, folio 1 recto)

These frontispieces belong to a long-standing practice of depicting presentation scenes in eastern Mediterranean manuscripts. A famous example comes from a 13th-century Arabic copy of Dioscorides’ De Materia Medica. Not unlike the image in the Coptic gospels, it opens with two men (students?) holding bound manuscripts, which they present to a seated figure represented on the facing page. This is the author Dioscorides, who extends a hand to receive the copies of his text.

Two students present De Materia Medica to Dioscorides, De Materia Medica, 1229, ink, opaque watercolor, and gold on paper, 19.2 x 14 cm (Topkapı Palace Library, Istanbul, MS Ahmed III. 2127, folios 1 verso–2 recto)

The following folio depicts Dioscorides seated with a student, holding a discussion about the mandrake root, one of the herbs treated in De Materia Medica. Together, the portraits visualize the transmission of scientific knowledge.

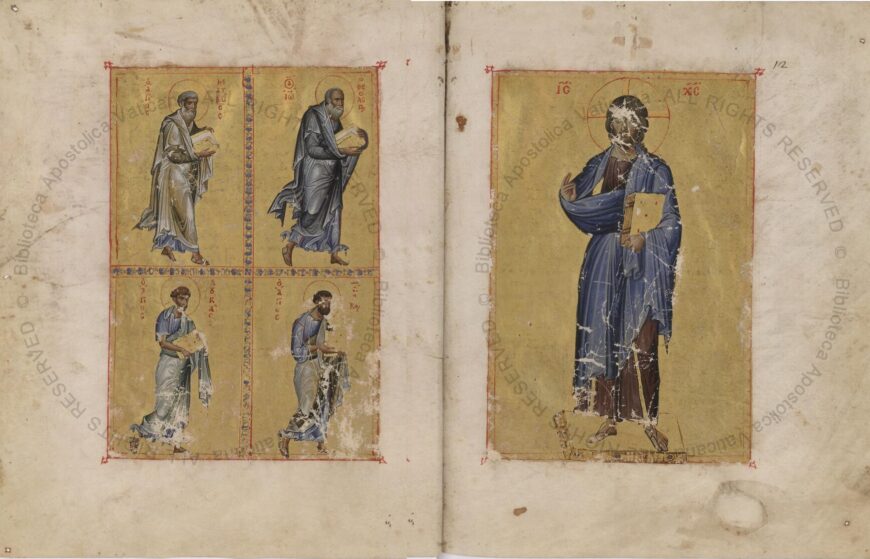

The four evangelists present the gospels to Christ. 11th-century Greek gospel book (Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Rome, MS Vat. Gr. 756, folios 11 verso–12 recto)

Christian painters employed the same theme to show the transmission of sacred (rather than scientific) knowledge. In an 11th-century gospel book, the four evangelists appear on a single page, each within his own quadrant, offering their texts to Christ, who holds a bible and turns to face the beholder. This pictorial formula can be found in diverse manuscripts written in Syriac, Frankish, and Armenian. Michael’s gospel book localizes this formula by showing the evangelists with Coptic gospels, emphasizing the language’s sanctity.

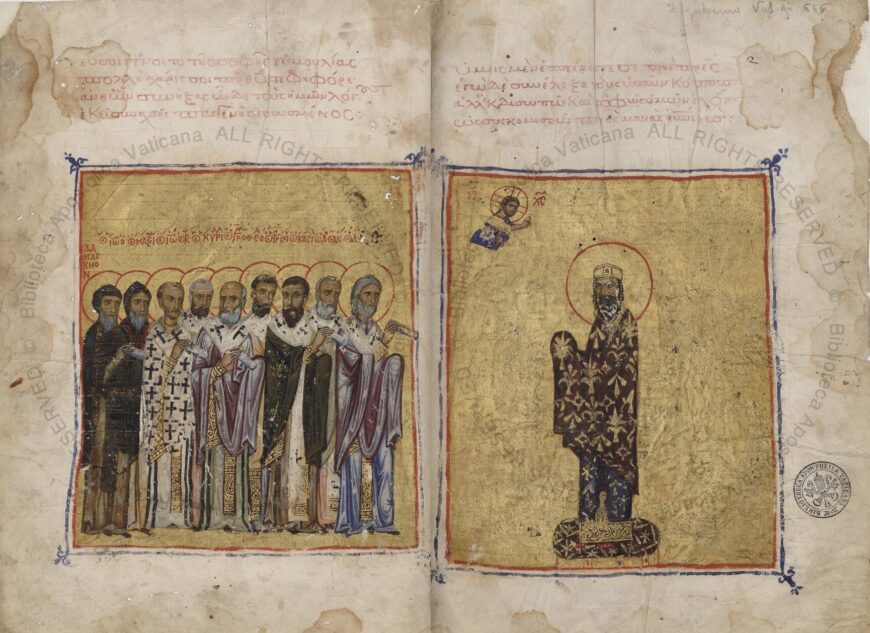

Emperor Alexios I Komnenos (1081–1118) receives Euthymios’ commentary from Church fathers, gospel commentary by Euthymios Zigabenos (c. 1100) (Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Rome, MS Vat. Gr. 666, folios 1 verso–2 recto)

Coptic artists may have been familiar with other variations on the presentation scene. For instance, a deluxe copy of a gospel commentary by the Greek theologian Euthymios Zigabenos employs multiple portraits to construct a chain of transmission that connects sacred and imperial figures. In a double frontispiece, the Byzantine emperor Alexios I Komnenos receives the manuscript that contains Euthymios’ commentary from a group of Church fathers.

Emperor Alexios I Komnenos (1081–1118) presents Euthymios’ commentary to Christ (Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Rome, MS Vat. Gr. 666, folio 2 verso)

On the next page, Alexios presents the commentary to an enthroned Christ. In these paintings, Euthymios’ wisdom is imparted to the emperor, who conveys his wisdom to Christ. It is likely that Michael’s gospels made a similar statement, drawing a parallel between Christ receiving the gospels from the evangelists and Mark III receiving the illuminated gospel book from Michael of Damietta. In either case, the frontispieces demonstrate how Coptic artists engaged with—and critically transformed—Mediterranean pictorial formulae to celebrate Coptic ecclesiastical authority.

Priestly attendant (detail), frontispiece, Gospel Book, 1178–80, ink, opaque watercolor, and gold on parchment, 38.5 x 27.5 cm (Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris, MS Copte 13, folio 1 recto)

The priest in Coptic and Arab painting

The priest also contributes to this message of patriarch authority. Here it is important to note that there are very few depictions of Black figures in Egyptian painting from the period—whether Arab or Christian. Their rarity has made interpretation of the figure in this image difficult. To further complicate matters, the priest occupies a marginal position in the painting. Not only is he crowded behind Mark III, but he is also the only figure in the frontispiece series who is not identified by an inscription, suggesting that he was never intended to be understood as a specific person.

Still, it is clear that the Black priest serves an important function. The artist has taken care to depict racial difference, showing Mark III with light skin and the priest with dark brown skin. His presence highlights the text of the inscription, which hails Mark III as the patriarch of Nubia and Ethiopia. Coptic patriarchs appointed metropolitans from Egypt to serve the Christian flocks of Nubia and Ethiopia. Whenever they needed a new metropolitan, Nubian and Ethiopian kings sent emissaries to Cairo, laden with gifts for both the Muslim ruler and Coptic patriarch.

In the 13th century, Ethiopian priests began to travel to monasteries in Egypt to copy religious texts, facilitating the transmission of religious knowledge to East Africa. The ties between Cairo and East Africa brought the patriarch both spiritual and political prestige, enhancing his standing within the Islamic court. By depicting the Black priest, the painter foregrounds a relationship that served as a source of Coptic pride. The depiction of the Black priest as an attendant to the patriarch alludes to the place of East Africa within the hierarchy of the Coptic Church, as a full—if subordinate—member.

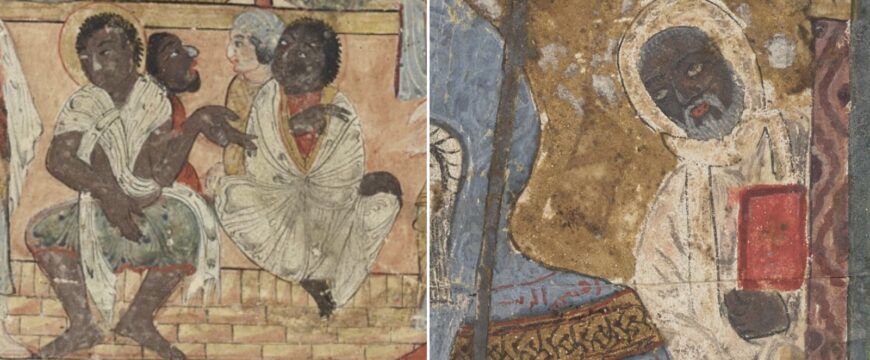

Enslaved sub-Saharan African men (detail), “Slave market at Zabid,” Maqamat of al-Hariri, 1237 (Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris, MS Arabe 5847, folio 105 recto); right: priestly attendant (detail), frontispiece, Gospel Book, 1178–80, ink, opaque watercolor, and gold on parchment, 38.5 x 27.5 cm (Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris, MS Copte 13, folio 1 recto)

The priest has significance beyond this manuscript. The Black figures in contemporary Arab painting are commonly depicted as enslaved men, often with stereotypical features such as dark skin, short black hair, and rough dress. In Arab painting, these enslaved figures are unidentified, and their function is to support the action of light-skinned elite figures.

The Black priest in Michael’s gospel book also occupies a marginal position and supports an elite, light-skinned figure. Yet he does so as a priest, an honored member of the Coptic ecclesiastical hierarchy. Though anonymous, the priest offers a pointed reminder that not all sub-Saharan Africans in Islamic lands came as enslaved men and women. Many Africans traveled freely as diplomats, pilgrims, merchants, artists, and religious scholars. By alerting us to other types of travelers and reasons for migration, the portrait of Mark III underscores the point that the paintings of Black men in Arab painting are selective and partial representations—not complete documents of medieval realities.